Poleaxe

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2014) |

The poleaxe (also pollaxe, pole-axe, pole axe, poleax, polax) is a European polearm that was used by medieval infantry.

Etymology

[edit]Most etymological authorities consider the poll- prefix historically unrelated to "pole", instead meaning "head".[1][2] However, some etymologists, including Eric Partridge, believe that the word is derived from "pole".[3]

The construction of the poleaxe

[edit]

The poleaxe design arose from the need to breach the plate armour of men at arms during the 14th and 15th centuries. Generally, the form consisted of a wooden haft some 1.5–2 m (4.9–6.6 ft) long, mounted with a steel head. It seems most schools of combat suggested a haft length comparable to the height of the wielder, but in some cases hafts appear to have been created up to 2.5 m (8.2 ft) in length.

The design of the head varied greatly with a variety of interchangeable parts and rivets. Generally, the head bore an axe head or hammer head mounted on ash or other hard-wood shafts from 4–6 ft in length, with a spike, hammer, or fluke on the reverse.[4] In addition, there was a spike or spear head projecting from the end of the haft which was often square in cross section, sometimes referred to as the "dague dessous".[4] The head was attached to the squared-off wooden pole by long flat strips of metal, called langets, which were riveted in place on either two or four of its sides to reinforce the pole against being chopped through in combat.[5] A round hilt-like disc called a rondelle was placed just below the head. They also appear to have borne one or two rings along the pole's length as places to prevent hands from slipping. Also of note is that the butt end of the staff, opposite the weapon's head, bore a spike or shoe.

On quick glance, the poleaxe is often confused with the similar-looking halberd. While they may have both been designed for hacking and piercing through armor plates, the axe blade on a poleaxe seems to have been consistently smaller than that of a halberd. A smaller head concentrates the kinetic energy of the blow on a smaller area, enabling the impact to defeat armour, while broader halberd heads are better against opponents with less mail or plate armour. Furthermore, many halberds had their heads forged as a single piece, while the poleaxe was typically modular in design.[6]

Fighting with poleaxe

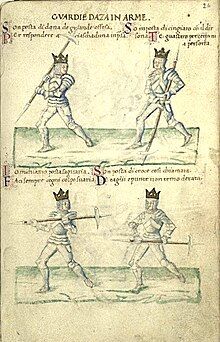

[edit]The poleaxe was used by knights and other men-at-arms (both noble and non-noble) in chivalric duels for prestige, to settle disputes in judicial duels, and of course on the battlefield.[7] It was a close range weapon that required ones full body strength and both hands to wield effectively.[4][8][7] The poleaxe has a sophisticated fighting technique, which is based on quarterstaff fighting. The blade of the poleaxe can be used, not only for simply hacking down the opponent, but also for tripping him, disarming him and blocking his blows. Both the head spike and butt spike can be used for thrusting attacks. The shaft itself is also a central part of the weapon, able to block the enemy's blows (the langets helping to reinforce the shaft), hit and push with the shaft held in both hands, or trip the opponent. The poleaxe's devastating efficiency is the origin of the term “to be poleaxed”, which dates from the 15th century when captives were often slain using poleaxe-blows to the head, and is now used to describe one being attacked or beat down in a brutal way, as if with a poleaxe.[9][4]

Many treatises on poleaxe fighting survive from the 15th and 16th centuries. Poleaxe fighting techniques have been rediscovered with the increasing interest in historical European martial arts.

Today the poleaxe is a weapon of choice of many medieval re-enactors. Rubber poleaxe heads designed for safe combat are available commercially.

Use in language

[edit]As a noun:[10]

- An ax having both a blade and a hammer face; used to slaughter cattle.

- (historical) A long-handled battle axe, being a combination of ax, hammer and pike.

As a transitive verb:[11]

- (transitive) To fell someone with, or as if with, a poleaxe.

- (transitive, figurative) To astonish; to shock or surprise utterly.

- (transitive, figurative) To stymie, thwart, cripple, paralyze.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The Oxford English Dictionary gives the following etymology, s.v. Poleaxe:

- [ME. pollax, polax, Sc. powax = MDu. polaex, pollaex, MLG. and LG. polexe, pollexe (whence MSw. 15th c. polyxe, pulyxe, MDa. polöxe), f. pol, POLL n.1, Sc. pow, MDu., MLG. polle, pol head + AXE: cf. MDu. polhamer = poll-hammer, also a weapon of war. It does not appear whether the combination denoted an axe with a special kind of head, or one for cutting off or splitting the head of an enemy.They were especially used for fighting Mounted infantry. In the 16th c. the word began to be written by some pole-axe (which after 1625 became the usual spelling), as if an axe upon a pole or long handle. This may have been connected with the rise of sense 2. Similarly, mod.Sw. pålyxa and Westphalian dial. pålexe have their first element = pole. Sense 3 may be a substitute for the earlier bole-axe, which was applied to a butcher's axe.]

- ^ Wise, Terence; Embleton, G.A. (1983). The Wars of the Roses. Men at Arms. Vol. 145. Osprey. p. 33. ISBN 0-85045-520-0.

- ^ For instance, Partridge gives the following etymology:

- L Palus, stake becomes OE pal, whence ME pol, pole, E Pole, the ME cpd pollax, polax becomes poleaxe, AE poleaxe: cf AX (E)

- ^ a b c d Price, Brian R. (2015). "The poleaxe: The changing face of warfare". Medieval Warfare. 5 (3): 36–38. ISSN 2211-5129. JSTOR 48578454.

- ^ Pollaxe, c. 1450, retrieved 2024-12-08

- ^ "The Poleaxe". Archived from the original on 2021-02-24. Retrieved 2019-11-21.

- ^ a b Deluz, Vincent (May 2017). "Le Jeu de la Hache: A Critical edition and dating discussion". Acta Periodica Duellatorum – via ResearchGate.

- ^ Price, Brian (August 2021). "THE MARTIAL ARTS OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE". University of North Texas ProQuest Dissertations & Theses: 169. ProQuest 1041248442 – via PROQUEST.

- ^ "Definition of POLEAX". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2024-12-09.

- ^ "Poleaxe". 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Poleaxe". 20 March 2023.

Further reading

- Schulze, André (ed.): Mittelalterliche Kampfesweisen. Band 2: Kriegshammer, Schild und Kolben. Mainz am Rhein: Zabern, 2007. ISBN 3-8053-3736-1

External links

[edit]- Le Jeu de la Hache

- Spotlight: The Medieval Poleaxe (myArmoury.com article)