Amazon molly

| Amazon molly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cyprinodontiformes |

| Family: | Poeciliidae |

| Genus: | Poecilia |

| Species: | P. formosa

|

| Binomial name | |

| Poecilia formosa (Girard, 1859)

| |

| Synonyms[2] | |

| |

The Amazon molly (Poecilia formosa) is a freshwater fish native to the warm waters of northeastern Mexico and the southern parts of the U.S. state of Texas.[1][3] It reproduces through gynogenesis, and essentially all individuals are females. The common name of "Amazon molly," acknowledges this trait as a reference to the Amazon warriors, a female-run society in Greek mythology.[4] The Amazon molly is a hybrid species, and its parent species are the sailfin molly (Poecilia latipinna) and the Atlantic molly (Poecilia mexicana).[5] In 1932, this species was the first vertebrate confirmed to be capable of asexual reproduction.[6]

Poecilia formosa gets its name from the Greek poikilos meaning "variegated" or "speckled," and the Latin formosa meaning "beautiful."[7]

Species description

[edit]The Amazon molly shares many of the same general characteristics of its parent species. Some of these characteristics include a rounded caudal fin, a small anal fin, small pelvic fins, pectoral fins located just behind the operculum, a small terminal mouth, and a compressed body shape. They are silver in color and are usually observed to have rows of reddish-brown spots along their sides. They are a small fish with an average length of 5.5cm. The maximum documented length for this species was recorded at 9.6cm.[8]

Amazon mollies have a small dorsal fin consisting of 10-12 soft rays.[9] The position of the dorsal fin on the back of the fish is anterior, closer towards the head, than the position of the anal fin on the underside of the fish. They do not have any spiny rays on their fins.[10]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The Amazon molly is native only to North America. Its habitat range extends from the Tuxapan River in northeastern Mexico to the Rio Grande and the Nueces River in southern Texas.[11] The hybridization event that resulted in the formation of the species Poecilia formosa is believed to have occurred near Tampico, Mexico. Distribution of the species would then have occurred outward from that region.[12]

In the 1930s, P. latipinna was introduced to the San Marcos River in central Texas.[13] A couple of decades later, in the 1950s, a few individuals of P. formosa were also introduced into the river. P. formosa was able to reproduce by using male P. latipinna as sperm donors, which allowed their population in the San Marcos to grow.[14]

Ecological Niche Modeling

The geographical range of the Amazon molly has been the primary research question of multiple scientific studies. Each of its parent species have a geographical range that extends beyond that of P. formosa.[15] P. mexicana's range extends from the Rio San Fernando drainage in northeastern Mexico southward into Costa Rica and Honduras. P. latipinna's range is more northern beginning around Veracruz, Mexico up to the U.S. state of North Carolina. The Amazon Molly only occupies a fraction of its parent species' habitats.[16]

In a study completed in 2010, researchers were able to identify two probable causes for the truncation of the habitat of the Amazon molly using a method called Ecological Niche Modeling (ENM).[17] At the northern limit of their native range, it was found that, even though sperm donor species were available, the environmental conditions were not suitable enough for the Amazon molly to thrive. At the southern limit of their native habitat, there was found to be both sperm donor species availability and suitable environmental conditions, indicating that dispersal availability was the limiting factor. Additionally, ENM found that the only suitable habitat not already occupied by the Amazon molly is in south Florida.[18]

The range of the Amazon molly overlaps somewhat with that of its parent species, but as a hybrid of two species with different ecological niches, it occupies its own distinct niche that lies somewhere between that of its parent species.[19]

Life history and ecology

[edit]P. formosa is an omnivore and feeds on both plant and animal matter.[20] Potential food items for the Amazon molly would include algae and small invertebrates like insects. Like other molly species, P. formosa prefers to live in sluggish, slow-moving bodies of water.[21] They have a lifespan of three to five years in captivity, but they are believed to live closer to five years in the wild.[22]

Reproduction

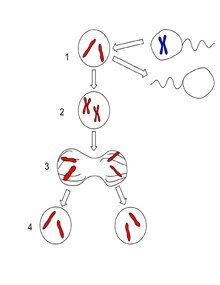

[edit]Reproduction is through gynogenesis, which is sperm-dependent parthenogenesis. This means that females must mate with a male of a closely related species, but the sperm only triggers reproduction and is not incorporated into the already diploid egg cells the mother is carrying (except in extraordinary circumstances). This results in clones of the mother being produced en masse.[23] This characteristic has led to the Amazon molly becoming an all-female species.[24] Other all-female species include the New Mexico whiptail, desert grassland whiptail lizard, and blue-spotted salamander.

In nature, the Amazon molly typically mates with a male from one of four different species, either P. latipinna, P. mexicana, P. latipunctata, or occasionally P. sphenops.[26] One other male that could possibly exist in the Amazon molly's natural range that could induce parthenogenesis in Amazon molly females is the triploid Amazon molly male.[citation needed] These triploid males are very rare in nature and are not necessary in the reproduction of the species, which is why the species is considered to be all female.[citation needed]

Since the male's sperm is not contributing to the genetic makeup of the offspring, it may seem non-beneficial for males of closely related species to participate in mating with the Amazon molly, though research shows that females of other species, such as the Atlantic molly, are trend conscious and are more likely to mate with a male of their species if they see that male mate with an Amazon molly.[27] Therefore, the Amazon molly can only live in habitats that are also occupied by a species of male that will reproduce with them.[24]

The Amazon molly reaches sexual maturity one to six months after birth, and typically has a brood between 60 and 100 fry (young) being delivered every 30–40 days. This lends itself to a large potential for population growth as long as host males are present. The wide variability in maturity dates and brood sizes is a result of genetic heritage, varying temperatures, and food availability. They become sexually mature faster and produce larger broods in warm (approximately 27 °C or 80 °F) water that provides an overabundance of food.[28]

The Amazon molly has been reproducing asexually for about 100,000-200,000 years.[29] This is about 500,000 generations of Amazon molly. Asexual lineages typically go extinct after 10,000-100,000 generations.[23] There is research being done to determine how the Amazon molly has not gone extinct or developed a Muller's ratchet of mutations. Researchers believe the answer is in the genome of the Amazon molly,[30] yet more research must be done to determine this.

P. formosa is a hybrid species and P. mexicana is one of the parental species.[31] Its other progenitor is most likely an extant, as yet undescribed, subspecies of P. latipinna or an extinct ancestor of P. latipinna.

Relationship to humans

[edit]The Amazon molly is regularly used in scientific research, particularly in the fields of biology, genetics, and evolutionary science.[32] This is largely due to the all-female, unisexual nature of the species as well as its unique means of asexual reproduction. It is also an easy fish to maintain in captivity, making it an ideal subject to keep in a laboratory setting.[33]

While the Amazon molly is not used in the pet trade, other molly species such as the sailfin molly, short-fin molly, and other selectively bred molly hybrids are commonly found in pet stores.[34]

Conservation status and potential threats

[edit]The conservation statures of Poecilia formosa by the International Union for the Conservation of nature (IUCN) was last assessed on 26 February 2019. Presently, the species is listed as Least Concern meaning there is not a high risk of extinction. However, the population trend is unknown. There is no data about whether the population might be growing or declining.[35]

Though localized threats such as pollution and other human disturbances to natural habitat could exist, there are currently no known threats to the Amazon molly.[36]

References

[edit]- ^ a b NatureServe.; Daniels, A. (2019). "Poecilia formosa". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T191747A130033075. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-2.RLTS.T191747A130033075.en. Retrieved 19 November 2021.

- ^ Eschmeyer, William N.; Fricke, Ron & van der Laan, Richard (eds.). "Poecilia formosa". Catalog of Fishes. California Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 3 April 2019.

- ^ Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.). "Poecilia formosa". FishBase. February 2019 version.

- ^ Schlupp, Ingo; Riesch, Rüdiger & Tobler, Michael (July 2007). "Amazon mollies". Current Biology. 17 (14): R536–R537. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.R536S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.012. PMID 17637348. S2CID 27224117.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Hubbs, Carl L.; Hubbs, Laura C. (30 December 1932). "Apparent Parthenogenesis in Nature, in a Form of Fish of Hybrid Origin". Science. 76 (1983): 628–630. doi:10.1126/science.76.1983.628.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Hubbs, Carl L.; Hubbs, Laura C. (30 December 1932). "Apparent Parthenogenesis in Nature, in a Form of Fish of Hybrid Origin". Science. 76 (1983): 628–630. doi:10.1126/science.76.1983.628.

- ^ "Poecilia formosa - Amazon molly". Fishes of Texas. Texas State University - San Marcos Department of Biology. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Hubbs, Carl L.; Hubbs, Laura C. (30 December 1932). "Apparent Parthenogenesis in Nature, in a Form of Fish of Hybrid Origin". Science. 76 (1983): 628–630. doi:10.1126/science.76.1983.628.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Drewry, George E.; Delco, Exalton A.; Hubbs, Clark (1 December 1958). "Occurence of the Amazon Molly, Mollensia formosa, at San Marcos, Texas" (PDF). The Texas Journal of Science. 10 (4): 489–490. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Schlupp, Ingo; Parzefall, Jakob; Schartl, Manfred (31 January 2002). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly, Poecilia formoa". Journal of Biogeography. 29 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2699.2002.00651.x. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ Costa, Gabriel C.; Schlupp, Ingo (8 June 2010). "Biogeography of the Amazon Molly: Ecological Niche and the Range of Limits of an Asexual Hybrid Species". Global Ecology and Biogeography. 19 (4): 442–451. doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2010.00546.x.

- ^ "Poecilia formosa - Amazon molly". Fishes of Texas. Texas State University - San Marcos Department of Biology. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ a b Heubel, Katja (2004). Population ecology and sexual preferences in the mating complex of the unisexual Amazon molly Poecilia formosa (GIRARD, 1859) (PhD). Universität Hamburg. S2CID 82258075.

- ^ a b Schlupp, Ingo; Riesch, Rüdiger; Tobler, Michael (July 2007). "Amazon mollies". Current Biology. 17 (14): R536–R537. Bibcode:2007CBio...17.R536S. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.012. PMID 17637348.

- ^ Janko, Karel; Eisner, Jan; Mikulíček, Peter (24 January 2019). "Sperm-dependent asexual hybrids determine competition among sexual species". Scientific Reports. 9 (1): 722. Bibcode:2019NatSR...9..722J. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35167-z. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 6345890. PMID 30679449.

- ^ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2019). "Poecilia formosa" in FishBase. February 2019 version.

- ^ Balcombe, Jonathan (2017). What a fish knows: the inner lives of our underwater cousins. Scientific American/Farrar, Straus, and Giroux. p. 190.

- ^ Fredjikrang. "The Importance of the Reproductive Techniques of Poecilia formosa". petfish.net. Archived from the original on 16 December 2006.

- ^ amazon-molly-genome-research (9 January 2019). "The Amazon Molly's Ability to Clone Itself". www.txstate.edu. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ "Survival of all-female fish species points to its DNA | Biodesign Institute | ASU". biodesign.asu.edu. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ^ Schartl, Manfred; Wilde, Brigitta; Schlupp, Ingo; Parzefall, Jakob (October 1995). "Evolutionary Origin of a Parthenoform, the Amazon Mollypoecilia Formosa, on the Basis of a Molecular Genealogy". Evolution; International Journal of Organic Evolution. 49 (5): 827–835. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1995.tb02319.x. PMID 28564866. S2CID 205779353.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ Leo, Nico; Neilson, Matt. "Amazon Molly (Poecilia formosa) - Species Profile". Nonindigenous Aquatic Species. U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "Poecilia formosa - Amazon molly". Fishes of Texas. Texas State University - San Marcos Department of Biology. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ "The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species - Amazon molly". Red List. IUCN. Retrieved 18 October 2024.

- ^ https://www.iucnredlist.org/search?query=amazon%20molly&searchType=species

- No sex for all-girl fish species BBC News, 23 April 2008

- Heubel, Katja U.: Population ecology and sexual preferences in the mating complex of the unisexual Amazon molly Poecilia formosa (Girard, 1859).Hamburg, University, Diss., 2004. [1]