Plant intelligence

Plant intelligence (also known as plant cognition or plant neurobiology) is a field of plant biology which aims to understand how plants process the information they obtain from their environment.[2][3][4] Plant neurobiological researchers claim that plants possess abilities associated with cognition including anticipation, decision making, learning and memory.[3][5][6]

Terminology used in plant neurobiology is rejected by the majority of plant scientists as misleading as plants do not possess consciousness or neurons.[7][8][9][10]

History

[edit]Early research

[edit]In 1811, James Perchard Tupper authored An Essay on the Probability of Sensation in Vegetables which argued that plants possess a low form of sensation.[11][12] He has been cited as an early botanist "attracted to the notion that the ability of plants to feel pain or pleasure demonstrated the universal beneficence of a Creator".[13]

The notion that plants are capable of feeling emotions was first recorded in 1848, when Gustav Fechner, an experimental psychologist, suggested that plants are capable of emotions and that one could promote healthy growth with talk, attention, attitude, and affection.[14] Federico Delpino wrote about plant intelligence in 1867.[15]

The idea of cognition in plants was explored by Charles Darwin in 1880 in the book The Power of Movement in Plants, co-authored with his son Francis. Using a neurological metaphor, he described the sensitivity of plant roots in proposing that the tip of roots acts like the brain of some lower animals. This involves reacting to sensation in order to determine their next movement.[16][17] Darwin's "root-brain hypothesis" influenced those in the field of plant neurobiology many years later.[17]

John Ellor Taylor in his 1884 book The Sagacity and Morality of Plants argued that plants are conscious agents.[18]

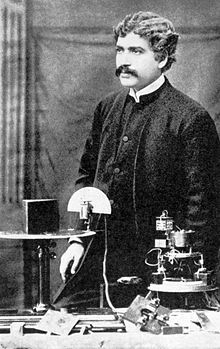

Jagadish Chandra Bose invented various devices and instruments to measure electrical responses in plants.[19][20] According to biologist Patrick Geddes "In his investigations on response in general Bose had found that even ordinary plants and their different organs were sensitive— exhibiting, under mechanical or other stimuli, an electric response, indicative of excitation."[21] One visitor to his laboratory, the vegetarian playwright George Bernard Shaw, was intensely disturbed upon witnessing a demonstration in which a cabbage had "convulsions" as it boiled to death.[22] Jagadish Chandra Bose is considered an important forerunner of plant neurobiology by proponents of plant cognition.[23][24][1] Bose was the author of The Nervous Mechanism of Plants, published in 1926. Karl F. Kellerman, Associate Chief of the Bureau of Plant Industry, United States Department of Agriculture criticized Bose's interpretation of the results from his experiments, stating that he failed to prove the conclusions from his reports that plants feel pain. Kellerman commented that "Sir Jagadar passed an electric current through plants, and his instruments recorded a break in the current. Such variations in resistance to electric current are found even when passing a current through dead matter".[25]

In 1900, ornithologist Thomas G. Gentry authored Intelligence in Plants and Animals which argued that plants have consciousness. Historian Ed Folsom described it as "an exhaustive investigation of how such animals as bees, ants, worms and buzzards, as well as all kinds of plants, display intelligence and thus have souls".[26] Captain Arthur Smith in the early 1900s authored the first article on "plant consciousness".[27][28] In 1905, Rev. Charles Fletcher Argyll Saxby authored a pamphlet, Do Plants Think? Some speculations concerning a neurology and psychology of plants.[29] Maurice Maeterlinck wrote about the intelligence of flowers in 1907.[30] Royal Dixon in his 1914 book, The Human Side of Plants argued that plants are sentient and have minds and souls.[31]

Cleve Backster

[edit]

In the 1960s Cleve Backster, an interrogation specialist with the CIA, conducted research that led him to believe that plants can feel and respond to emotions and intents from other organisms including humans. Backster's interest in the subject began in February 1966 when he tried to measure the rate at which water rises from a philodendron's root into its leaves. Because a polygraph or "lie detector" can measure electrical resistance, which would alter when the plant was watered, he attached a polygraph to one of the plant's leaves. Backster stated that, to his immense surprise, "the tracing began to show a pattern typical of the response you get when you subject a human to emotional stimulation of short duration".[32] His ideas about primary perception (plants responding to emotions and intents) became known as the "Backster effect".[33][34]

In 1975, K. A. Horowitz, D. C. Lewis and E. L. Gasteiger published an article in Science giving their results when repeating one of Backster's effects – plant response to the killing of brine shrimp in boiling water.[35] The researchers grounded the plants to reduce electrical interference and rinsed them to remove dust particles. As a control, three of five pipettes contained brine shrimp while the remaining two only had water; the pipettes were delivered to the boiling water at random. This investigation used a total of 60 brine shrimp deliveries to boiling water while Backster's had used 13. Positive correlations did not occur at a rate great enough to be considered statistically significant.[35] Other controlled experiments that attempted to replicate Backster's findings also produced negative results.[36][37][38][39]

Botanist Arthur Galston and physiologist Clifford L. Slayman who investigated Backster's claims wrote:

There is no objective scientific evidence for the existence of such complex behaviour in plants. The recent spate of popular literature on "plant consciousness" appears to have been triggered by "experiments" with a lie detector, subsequently reported and embellished in a book called The Secret Life of Plants. Unfortunately, when scientists in the discipline of plant physiology attempted to repeat the experiments, using either identical or improved equipment, the results were uniformly negative. Further investigation has shown that the original observations probably arose from defective measuring procedures.[36]

John M. Kmetz noted that the Backster effect was based on observations of only seven plants which nobody including Backster was able to replicate.[33]

The television show MythBusters also performed experiments (season 4, episode 18, 2006) to test the concept. The tests involved connecting plants to a polygraph galvanometer and employing actual and imagined harm upon the plants or upon others in the plants' vicinity. The galvanometer showed a reaction about one third of the time. The experimenters, who were in the room with the plant, posited that the vibrations of their actions or the room itself could have affected the polygraph. After isolating the plant, the polygraph showed a response slightly less than one third of the time. Later experiments with an EEG failed to detect anything. The show concluded that the results were not repeatable, and that the theory was not true.[40]

Backster's research was cited in the pseudoscientific book The Secret Life of Plants in 1973.[35][41] Whilst the book captured public attention it severely damaged the credibility of the field of plant intelligence. Philosopher Yogi H. Hendlin noted that the book's "combination of haphazard, panpsychist metaphysical speculations and unmethodical citizen science stigmatised legitimate progressive plant research, alongside the era’s new-age pseudoscience, tarring the discipline’s serious inquiry".[42]

Dorothy Retallack

[edit]In 1973, Dorothy Retallack authored The Sound of Music and Plants.[43] In the book Retallack records experiments she conducted at Temple Buell College on applying different music to plants. She stated that the plants died in response to acid rock but flourished in response to classical music and jazz.[44]

The experiments were described as pseudoscientific as they were poorly designed and did not control for other factors such as humidity, light or water.[45] Colorado Women's College was embarrassed by the experiments.[44]

Modern research

[edit]Anthony Trewavas is credited with reintroducing the idea of plant intelligence in the early 2000s.[30][46][47] In 2003, Trewavas led a study to see how the roots interact with one another and study their signal transduction methods. He was able to draw similarities between water stress signals in plants affecting developmental changes and signal transductions in neural networks causing responses in muscle.[46] Particularly, when plants are under water stress, there are abscisic acid dependent and independent effects on development.[48] This brings to light further possibilities of plant decision-making based on its environmental stresses. The integration of multiple chemical interactions show evidence of the complexity in these root systems.[49]

In 2012, Paco Calvo Garzón and Fred Keijzer speculated that plants exhibited structures equivalent to (1) action potentials (2) neurotransmitters and (3) synapses. Also, they stated that a large part of plant activity takes place underground, and that the notion of a 'root brain' was first mooted by Charles Darwin in 1880. Free movement was not necessarily a criterion of cognition, they held. The authors gave five conditions of minimal cognition in living beings, and concluded that 'plants are cognitive in a minimal, embodied sense that also applies to many animals and even bacteria.'[50] In 2017 biologists from University of Birmingham announced that they found a "decision-making center" in the root tip of dormant Arabidopsis seeds.[51]

In 2014, Anthony Trewavas released a book called Plant Behavior and Intelligence that highlighted a plant's cognition through its colonial-organization skills reflecting insect swarm behaviors.[52] This organizational skill reflects the plant's ability to interact with its surroundings to improve its survivability, and a plant's ability to identify exterior factors. Evidence of the plant's minimal cognition of spatial awareness can be seen in their root allocation relative to neighboring plants.[50] The organization of these roots have been found to originate from the root tip of plants.[53]

On the other hand, Peter A. Crisp and his colleagues proposed a different view on plant memory in their review: plant memory could be advantageous under recurring and predictable stress; however, resetting or forgetting about the brief period of stress may be more beneficial for plants to grow as soon as the desirable condition returns.[54]

Affifi (2018) proposed an empirical approach to examining the ways plants model coordinate goal-based behaviour to environmental contingency as a way of understanding plant learning.[55] According to this author, associative learning will only demonstrate intelligence if it is seen as part of teleologically integrated activity. Otherwise, it can be reduced to mechanistic explanation.

In 2017 Yokawa, K. et al. found that, when exposed to anesthetics, a number of plants lost both their autonomous and touch-induced movements. Venus flytraps no longer generate electrical signals and their traps remain open when trigger hairs were touched, and growing pea tendrils stopped their autonomous movements and were immobilized in a curled shape.[56]

Raja et al (2020) found that potted French bean plants, when planted 30 centimetres from a garden cane, would adjust their growth patterns to enable themselves to use the cane as a support in the future. Raja later stated that "If the movement of plants is controlled and affected by objects in their vicinity, then we are talking about more complex behaviours (rather than simple) reactions". Raja proposed that researchers should look for corresponding cognitive signatures.[57][58]

A minority of researchers within the field of plant neurobiology argue that plants are conscious organisms.[59][60][61] Peter Wohlleben argued for plant sentience in his 2016 book The Hidden Life of Trees.[62] The book was widely criticized by biologists and forest scientists for using strong anthropomorphic and teleological language such as describing trees as having friendships and registering fear, love and pain.[62] It has been described as containing a "conglomeration of half-truths, biased judgements, and wishful thinking".[62] František Baluška argues for a model called the Cellular Basis of Consciousness (CBC) which proposes that all cells are conscious.[59] The model has been criticized for being based on only speculation and lacking empirical evidence for its claim that cells have consciousness.[63][64]

Organizations

[edit]Modern research on plant cognition is conducted by researchers associated with the Society for Plant Neurobiology that was established in 2005.[6] Due to criticisms from botanists and complaints from early members that affiliations with the Society were negatively impacting their careers, the Society was renamed the Society of Plant Signaling and Behavior (SPSB) in 2009.[6][65] Research on plant intelligence is also conducted by the International Laboratory of Plant Neurobiology headed by Stefano Mancuso. It has been described as "the world's only laboratory dedicated to plant intelligence".[66]

Criticism

[edit]The idea of plant cognition is a source of controversy and is rejected by the majority of plant scientists.[7][8][9][67] Plant neurobiology has been criticized for misleading the public with false terminology.[8][68] There is no scientific evidence that plants possess consciousness or are sentient.[7][8][9][69]

Amadeo Alpi and 35 other scientists published an article in 2007 titled "Plant Neurobiology: No Brain, No Gain?" in Trends in Plant Science.[7] In this article, they argue that since there is no evidence for the presence of neurons in plants, the idea of plant neurobiology and cognition is unfounded and needs to be redefined.[7] They commented that "plant neurobiology does not add to our understanding of plant physiology, plant cell biology or signaling".[7] In response to this article, Francisco Calvo Garzón published an article in Plant Signaling and Behavior.[5] He states that, while plants do not have neurons as animals do, they do possess an information-processing system composed of cells. He argues that this system can be used as a basis for discussing the cognitive abilities of plants.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Minorsky, Peter V. (2021). "American racism and the lost legacy of Sir Jagadis Chandra Bose, the father of plant neurobiology". Plant Signal Behav. 16 (1): 1818030. doi:10.1080/15592324.2020.1818030. PMC 7781790. PMID 33275072.

- ^ Brenner ED, Stahlberg R, Mancuso S, Vivanco J, Baluska F, Van Volkenburgh E. (2006). "Plant neurobiology: an integrated view of plant signaling". Trends Plant Sci. 11 (8): 413–419. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2006.06.009. PMID 16843034.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Lee, Jonny (2023). "What is cognitive about 'plant cognition'?". Biology & Philosophy. 38 (18). doi:10.1007/s10539-023-09907-z.

- ^ Trewavas, Anthony (2017). "The foundations of plant intelligence". Interface Focus. 7 (3): 20160098. doi:10.1098/rsfs.2016.0098. PMC 5413888. PMID 28479977.

- ^ a b Garzón FC (July 2007). "The quest for cognition in plant neurobiology". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2 (4): 208–11. Bibcode:2007PlSiB...2..208C. doi:10.4161/psb.2.4.4470. PMC 2634130. PMID 19516990.

- ^ a b c Minorsky, Peter V. (2024). "The "plant neurobiology" revolution". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 19 (1). doi:10.1080/15592324.2024.2345413. PMC 11085955. PMID 38709727.

- ^ a b c d e f Alpi A, Amrhein N, Bertl A, Blatt MR, Blumwald E, Cervone F, et al. (April 2007). "Plant Neurobiology: No Brain, No Gain?". Trends in Plant Science. 12 (4): 135–6. Bibcode:2007TPS....12..135A. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2007.03.002. PMID 17368081.

- ^ a b c d Taiz, Lincoln; Alkon, Daniel; Draguhn, Andreas; Murphy, Angus; Blatt, Michael; Hawes, Chris; Thiel, Gerhard; Robinson, David G. (2019). "Plants Neither Possess nor Require Consciousness". Trends in Plant Science. 24 (8): 677–687. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.008. PMID 31279732.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Mallatt J, Blatt MR, Draguhn A, Robinson DG, Taiz L. (2020). "Debunking a myth: plant consciousness". Protoplasma. 258 (3): 459–476. doi:10.1007/s00709-020-01579-w. PMC 8052213. PMID 33196907.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Pigliucci, Massimo (2024). "Are Plants Conscious?". Skeptical Inquirer. 48 (5).

- ^ Macdougal, D. T. (1895). "Irritability and Movement in Plants". Popular Science Monthly. 47: 225–234.

- ^ Sha, Richard C. (2009). Perverse Romanticism: Aesthetics and Sexuality in Britain, 1750–1832. Johns Hopkins University. pp. 60-61. ISBN 978-0-8018-9041-3

- ^ Whippo, Craig W; Hangarter, Roger P. (2009). "The "Sensational" Power of Movement in Plants: A Darwinian System for Studying the Evolution of Behavior". American Journal of Botany. 96 (12): 2115–2127. doi:10.3732/ajb.0900220. PMID 21622330.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Heidelberger, Michael. (2004). Nature From Within: Gustav Theodor Fechner and his Psychophysical Worldview. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-8229-4210-0

- ^ Mancuso S (September 2010). "Federico Delpino and the foundation of plant biology". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 5 (9): 1067–71. Bibcode:2010PlSiB...5.1067M. doi:10.4161/psb.5.9.12102. PMC 3115070. PMID 21490417.

- ^ Darwin, C. (1880). The Power of Movement in Plants. London: John Murray. Darwin Online : "The course pursued by the radicle in penetrating the ground must be determined by the tip; hence it has acquired such diverse kinds of sensitiveness. It is hardly an exaggeration to say that the tip of the radicle thus endowed, and having the power of directing the movements of the adjoining parts, acts like the brain of one of the lower animals; the brain being seated within the anterior end of the body, receiving impressions from the sense-organs, and directing the several movements."

- ^ a b Baluška, František; Mancuso, Stefano; Volkmann, Dieter; Barlow, Peter (2009). "The 'root-brain' hypothesis of Charles and Francis Darwin". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 4 (12): 1121–1127. Bibcode:2009PlSiB...4.1121B. doi:10.4161/psb.4.12.10574. PMC 2819436. PMID 20514226.

- ^ "The Sagacity of Plants". The Month. 57 (264): 217–225. 1886.

- ^ Galston, Arthur W; Slayman, Clifford L. (1979). "The Not-So-Secret Life of Plants" (PDF). American Scientist. 67 (3): 337–344. JSTOR 27849226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ V. A Shepard cited in Alexander Volkov. (2012). Plant Electrophysiology: Methods and Cell Electrophysiology. Springer. p. 12. ISBN 978-3-642-29119-7 "Bose began by applying delicate instrumentation he had invented in his semiconductor research to deliver electrical stimuli and record electrical responses from various plant parts... He discovered that both living animal and plant tissues exhibited a diminution of sensitivity after continuous stimulation, recovery after rest, a 'staircase' or summation of electrical effects following mechanical stimulation, abolition of current flow after applying poisons and reduced sensitivity at low temperature."

- ^ Geddes, Patrick. (1920). The Life and Work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose. Longmans, Green & Company. p. 120

- ^ Geddes, Patrick. (1920). The Life and Work of Sir Jagadis C. Bose. Longmans, Green & Company. p. 146

- ^ Kingsland, Sharon E; Taiz, Lincoln (2024). "Plant "intelligence" and the misuse of historical sources as evidence". Protoplasma. doi:10.1007/s00709-024-01988-1. PMID 39276228.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Tandon PN (2019). "Jagdish Chandra Bose & plant neurobiology". Indian J Med Res. 149 (5): 593–599. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_392_19. PMC 6702694. PMID 31417026.

- ^ "Pain in Plants". The Florists' Review. 58 (4): 36. 1926.

- ^ Folsom, Ed (1983). "The Mystical Ornithologist and the Iowa Tufthunter: Two Unpublished Whitman Letters and Some Identifications" (PDF). Walt Whitman Quarterly Review. 1: 18–29. doi:10.13008/2153-3695.1003.

- ^ Smith, Arthur (1907). "Plant Consciousness". The Arena. 37 (211): 570–576.

- ^ Smith, Arthur (1913). "The Brain Power of Plants". Gardener's Chronicle of America. 16 (5): 427–429.

- ^ "Do Plants Think?". The Gardeners' Chronicle. 3 (39): 57. 1906.

- ^ a b Cvrcková F, Lipavská H, Zárský V. (2009). "Plant intelligence: Why, why not or where?". Plant Signal Behav. 4 (5). doi:10.4161/psb.4.5.8276. PMC 2676749. PMID 19816094.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "(1) The Hundred Best Animals (2) True Stories about Horses (3) The Human Side of Plants". Nature. 96 (2400): 225–226. 1915. Bibcode:1915Natur..96..225.. doi:10.1038/096225a0. S2CID 3968327.

- ^ Backster, Cleve. (2003). Primary Perception: Biocommunication with Plants, Living Foods, and Human Cells. White Rose Millennium Press. ISBN 978-0966435436

- ^ a b Kmetz, John M. (1978). "Plant Primary Perception: The Other Side of the Leaf" (PDF). Skeptical Inquirer. 2 (2): 57–61.

- ^ Jensen, Derrick (1997). "The Plants Respond". The Sun. Archived from the original on July 23, 2024.

- ^ a b c Horowitz KA, Lewis DC, Gasteiger EL (1975). "Plant "primary perception": electrophysiological unresponsiveness to brine shrimp killing". Science. 189 (4201): 478–480. doi:10.1126/science.189.4201.478.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Galston, Arthur W; Slayman, Clifford L. Plant Sensitivity and Sensation. In George Ogden Abell, Barry Singer. (1981). Science and the Paranormal: Probing the Existence of the Supernatural. Junction Books. pp. 40-55. ISBN 0-86245-037-3

- ^ Schwebs, Ursula. (1973). Do Plants Have Feelings? Harpers. pp. 75-76

- ^ Chedd, Graham. (1975). AAAS takes on Emotional Plants. New Scientist. 13 February. pp. 400-401

- ^ Neher, Andrew. (2011). Paranormal and Transcendental Experience: A Psychological Examination. Dover Publications. pp. 155-156. ISBN 978-0486261676

- ^ "Episode 61: Deadly Straw, Primary Perception". Annotated Mythbusters. September 6, 2006. Archived from the original on May 15, 2021. Retrieved February 28, 2010.

- ^ Mescher, Mark C; Moraes, Consuelo M. De (2015). "Role of plant sensory perception in plant–animal interactions". Journal of Experimental Biology. 66 (2): 425–433. doi:10.1093/jxb/eru414. hdl:20.500.11850/95438.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hendlin, Yogi H. (2022). "Plant Philosophy and Interpretation" (PDF). Environmental Values. 31 (3): 253–276. doi:10.3197/096327121X16141642287755.

- ^ "The inner life of plants". The Week. 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ a b Ribley, Anthony (1971). "Rock or Bach an Issue to Plants, Singer Says". The New York Times.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Chalker-Scott, Linda (2008). The Informed Gardener (PDF). University of Washington Press. pp. 5–9. ISBN 978-0295987903. JSTOR j.ctvcwnb45.4.

- ^ a b Trewavas A (July 2003). "Aspects of plant intelligence". Annals of Botany. 92 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1093/aob/mcg101. PMC 4243628. PMID 12740212.

- ^ Trewavas, Anthony (2002). "Plant intelligence: Mindless mastery". Nature. 415 (841). doi:10.1038/415841a.

- ^ Shinozaki K (2000). "Molecular responses to dehydration and low temperature: differences and cross-talk between two stress signaling pathways". Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 3 (3): 217–223. doi:10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00067-4. PMID 10837265.

- ^ McCully ME (June 1999). "ROOTS IN SOIL: Unearthing the Complexities of Roots and Their Rhizospheres". Annual Review of Plant Physiology and Plant Molecular Biology. 50: 695–718. doi:10.1146/annurev.arplant.50.1.695. PMID 15012224.

- ^ a b Garzon P, Keijzer F (2011). "Plants: Adaptive behavior, root-brains, and minimal cognition" (PDF). Adaptive Behavior. 19 (3): 155–171. doi:10.1177/1059712311409446. S2CID 5060470.

- ^ Topham AT, Taylor RE, Yan D, Nambara E, Johnston IG, Bassel GW (June 2017). "Temperature variability is integrated by a spatially embedded decision-making center to break dormancy in Arabidopsis seeds". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 114 (25): 6629–6634. Bibcode:2017PNAS..114.6629T. doi:10.1073/pnas.1704745114. PMC 5488954. PMID 28584126.

- ^ Trewavas 2014, p. 95-96.

- ^ Trewavas 2014, p. 140.

- ^ Crisp PA, Ganguly D, Eichten SR, Borevitz JO, Pogson BJ (February 2016). "Reconsidering plant memory: Intersections between stress recovery, RNA turnover, and epigenetics". Science Advances. 2 (2): e1501340. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1340C. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1501340. PMC 4788475. PMID 26989783.

- ^ Affifi R (2018). "Deweyan Psychology in Plant Intelligence Research: Transforming Stimulus and Response". In Baluska F, Gagliano M, Witzany G (eds.). Memory and Learning in Plants. Signaling and Communication in Plants. Cham.: Springer. pp. 17–33. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-75596-0_2. ISBN 978-3-319-75595-3.

- ^ Yokawa, K; Kagenishi, T; Pavlovič, A; Gall, S; Weiland, M; Mancuso, S; Baluška, F (11 December 2017). "Anaesthetics stop diverse plant organ movements, affect endocytic vesicle recycling and ROS homeostasis, and block action potentials in Venus flytraps". Annals of Botany. 122 (5): 747–756. doi:10.1093/aob/mcx155. PMC 6215046. PMID 29236942.

- ^ "Plants: Are they conscious?". BBC Science Focus Magazine. 5 February 2021. Retrieved 6 February 2021.

- ^ Raja, Vicente; Silva, Paula L.; Holghoomi, Roghaieh; Calvo, Paco (December 2020). "The dynamics of plant nutation". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 19465. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1019465R. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-76588-z. PMC 7655864. PMID 33173160.

- ^ a b Reber, Arthur S; Baluška, František (2021). "Cognition in some surprising places". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 564: 150–157. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2020.08.115.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Mallatt J, Taiz L, Draguhn A, Blatt MR, Robinson DG. (2021). "Integrated information theory does not make plant consciousness more convincing". Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 564: 166–169. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.022. PMID 33485631.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hansen, Mads Jørgensen (2024). "A critical review of plant sentience: moving beyond traditional approaches". Biology & Philosophy. 39 (13). doi:10.1007/s10539-024-09953-1.

- ^ a b c Kingsland, Sharon Elizabeth (2018). "Facts or Fairy Tales? Peter Wohlleben and the Hidden Life of Trees". Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. 99 (4): e01443. doi:10.1002/bes2.1443.

- ^ Key, Brian (2016). ""Cellular basis of consciousness": Not just radical but wrong". Animal Sentience. 11 (5): 1–2. doi:10.51291/2377-7478.1163.

- ^ Robinson DG, Mallatt J, Peer WA, Sourjik V, Taiz L. (2024). "Cell consciousness: a dissenting opinion: The cellular basis of consciousness theory lacks empirical evidence for its claims that all cells have consciousness". EMBO Reports. 25 (5): 2162–2167. doi:10.1038/s44319-024-00127-4. PMC 11094104. PMID 38548972.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nasser, Latif (2012). "The long, strange quest to detect plant consciousness". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on November 30, 2024.

- ^ "Smarty Plants: Inside the World's Only Plant-Intelligence Lab". Wired. 2007.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Draguhn A, Mallatt JM, Robinson DG. (2021). "Anesthetics and plants: no pain, no brain, and therefore no consciousness". Protoplasma. 258 (2): 239–248. doi:10.1007/s00709-020-01550-9. PMC 7907021. PMID 32880005.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Robinson, David G; Draguhn, Andreas; Taiz, Lincoln (2020). "Plant "intelligence" changes nothing". EMBO Reports. 21 (5): e50395. doi:10.15252/embr.202050395. PMC 7202214. PMID 32301219.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hamilton, Adam; McBrayer, Justin (2020). "Do Plants Feel Pain?". Disputatio. 12 (56): 71–98. doi:10.2478/disp-2020-0003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Further reading

[edit]Plant intelligence and neurobiology

[edit]- Baluska F, Mancuso S. (2009). "Plant neurobiology: from sensory biology, via plant communication, to social plant behavior". Cogn Process. 1: S3-7. doi:10.1007/s10339-008-0239-6. PMID 18998182.

- Calvo P, Gagliano M, Souza GM, Trewavas A. (2020). "Plants are intelligent, here's how". Annals of Botany. 125 (1): 11–28. doi:10.1093/aob/mcz155. PMC 6948212. PMID 31563953.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ferretti, Gabriele (2024). Philosophy of Plant Cognition: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Routledge. ISBN 978-1032493510.

- Garzón FC (July 2007). "The quest for cognition in plant neurobiology". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 2 (4): 208–11. Bibcode:2007PlSiB...2..208C. doi:10.4161/psb.2.4.4470. PMC 2634130. PMID 19516990.

- Mancuso, Stefano (2019). Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence. Island Press. ISBN 978-1610917315.

- Pollan, Michael (2013). "The Intelligent Plant". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on December 4, 2024.

- Manetas, Yiannis (2012). "Are Plants Intelligent Organisms After All?". Alice in the Land of Plants. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg. pp. 323–342. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-28338-3_10. ISBN 978-3-642-28337-6.

- Minorsky, Peter V. (2024). "The "plant neurobiology" revolution". Plant Signaling & Behavior. 19 (1). doi:10.1080/15592324.2024.2345413. PMC 11085955. PMID 38709727.

- Schlanger, Zoë (2024). The Light Eaters: How the Unseen World of Plant Intelligence Offers a New Understanding of Life on Earth. New York: Harper. ISBN 9780063073852. OCLC 1421933387. Archived from the original on 16 April 2024. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- Segundo-Ortin M, Calvo P. (2022). "Consciousness and cognition in plants". Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 13 (2): e1578. doi:10.1002/wcs.1578. PMID 34558231.

- Trewavas AJ (2014). Plant Behaviour and Intelligence. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-953954-3. OCLC 890389682.

- Trewavas, Anthony (2003). "Aspects of Plant Intelligence". Annals of Botany. 92 (1): 1–20. doi:10.1093/aob/mcg101. PMC 4243628. PMID 12740212.

Criticism

[edit]- "No, plants don't have feelings". The Week. 2015. Archived from the original on October 29, 2023.

- Firn, Richard (2004). "Plant Intelligence: An Alternative Point of View". Annals of Botany. 93 (4): 345–351. doi:10.1093/aob/mch058. PMC 4242337. PMID 15023701.

- Galston, Arthur W; Slayman, Clifford L. (1979). "The Not-So-Secret Life of Plants" (PDF). American Scientist. 67 (3): 337–344. JSTOR 27849226.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Hamilton, Adam; McBrayer, Justin (2020). "Do Plants Feel Pain?". Disputatio. 12 (56): 71–98. doi:10.2478/disp-2020-0003.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Kingsland, Sharon E; Taiz, Lincoln (2024). "Plant "intelligence" and the misuse of historical sources as evidence". Protoplasma. doi:10.1007/s00709-024-01988-1. PMID 39276228.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mallatt J, Blatt MR, Draguhn A, Robinson DG, Taiz L. (2020). "Debunking a myth: plant consciousness". Protoplasma. 258 (3): 459–476. doi:10.1007/s00709-020-01579-w. PMC 8052213. PMID 33196907.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Mallatt, Jon; Robinson, David G; Blatt, Michael R; Draguhn, Andreas; and Taiz, Lincoln (2023). "Plant sentience: The burden of proof". Animal Sentience. 33 (15): 1–10. doi:10.51291/2377-7478.1802.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Rensberger, Boyce (1975). "Idea That Plants Emote Is Rebutted". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2019.

- Robinson DG, Draguhn A. (2021). "Plants have neither synapses nor a nervous system". J Plant Physiol. 263: 153467. doi:10.1016/j.jplph.2021.153467. PMID 34247030.

- Taiz, Lincoln; Alkon, Daniel; Draguhn, Andreas; Murphy, Angus; Blatt, Michael; Hawes, Chris; Thiel, Gerhard; Robinson, David G. (2019). "Plants Neither Possess nor Require Consciousness". Trends in Plant Science. 24 (8): 677–687. doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2019.05.008. PMID 31279732.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

[edit]- Plant perception (a.k.a. the Backster effect)

- Society of Plant Signaling and Behavior (formerly Society for Plant Neurobiology)