Peter Gabriel

Peter Gabriel | |

|---|---|

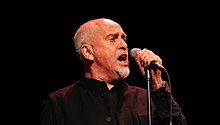

Gabriel performing in October 2023 | |

| Background information | |

| Born | 13 February 1950 Chobham, England |

| Genres | |

| Occupations |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1965–present |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | |

| Spouses | Jill Moore

(m. 1971; div. 1987)Meabh Flynn (m. 2002) |

| Website | petergabriel |

| Signature | |

| |

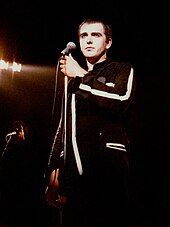

Peter Brian Gabriel (born 13 February 1950) is an English singer, songwriter, musician, and human rights activist. He came to prominence as the original frontman of the rock band Genesis.[1] He left the band in 1975 and launched a solo career with "Solsbury Hill" as his first single. After releasing four successful studio albums, all titled Peter Gabriel, his fifth studio album So (1986) became his best-selling release and is certified triple platinum in the UK and five times platinum in the US. The album's most successful single, "Sledgehammer", won a record nine MTV Awards at the 1987 MTV Video Music Awards. A 2011 Time report said "Sledgehammer" was the most played music video of all time on MTV.[2]

A supporter of world music for much of his career, Gabriel co-founded the World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) festival in 1982,[3] and has continued to produce and promote world music through his Real World Records label. He has pioneered digital distribution methods for music and co-founded OD2, one of the first online music download services.[4] He has also been involved in numerous humanitarian efforts. In 1980, he released the anti-apartheid single "Biko". He has participated in several human rights benefit concerts, including Amnesty International's Human Rights Now! tour in 1988, and co-founded the human rights organisation Witness in 1992.[3] He developed the idea for The Elders, an organisation of public figures noted as peace activists, alongside Nelson Mandela and Richard Branson in 2007.[5]

Gabriel has won three Brit Awards,[6] six Grammy Awards,[7] 13 MTV Video Music Awards, the first Pioneer Award at the BT Digital Music Awards,[8] the Q Lifetime Achievement,[9] the Ivor Novello Award for Lifetime Achievement,[10] and the Polar Music Prize.[11] He was named a BMI Icon at the 57th annual BMI London Awards for his "influence on generations of music makers".[12] In recognition of his human rights activism, he received the Man of Peace award from the Nobel Peace Prize laureates in 2006,[13] and Time magazine named him one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2008.[14] AllMusic described him as "one of rock's most ambitious, innovative musicians, as well as one of its most political".[15] He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a member of Genesis in 2010,[16] and as a solo artist in 2014.[17] In recognition of his musical achievements, he was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of South Australia in 2015.

Early life

[edit]Peter Brian Gabriel was born in Chobham on 13 February 1950, the son of Edith Irene (1921–2016) and Ralph Parton Gabriel (1912–2012). His paternal grandfather was Colonel Edward Allen, chairman of the Civil Service Department Store on London's Strand. His mother came from a musical family, while his father was an electrical engineer and dairy farm owner from a long-established family of London timber importers and merchants. He was raised at Deep Pool Farm, a Victorian manor near Chobham.[18][19] His great-great-great-uncle, Sir Thomas Gabriel, 1st Baronet, was Lord Mayor of London from 1866 to 1877.[20] Gabriel attended the private primary school Cable House in Woking and St Andrews Preparatory School for Boys in Horsell.[18] During his time at the latter, his teachers noticed his singing talent, but he instead opted for piano lessons from his mother and developed an interest in drumming. At age 10, he purchased a floor tom-tom.[21]

Gabriel later remarked of his early influences, "Hymns played quite a large part. They were the closest I came to soul music before I discovered soul music. There are certain hymns that you can scream your lungs out on, and I used to love that. It was great when you used to get the old shivers down the back."[22] He wrote his first song, "Sammy the Slug", at age 12. An aunt gave him money for professional singing lessons around this time, but he used it to buy the Beatles' debut album Please Please Me, which had just been released.[21] In September 1963, he started at the public Charterhouse School in Godalming.[23] There, he was a drummer and vocalist for his first band, the trad jazz outfit the Milords (or M'Lords). This was followed by a holiday band called the Spoken Word,[24] which recorded an acetate in 1966.[25] Gabriel played drums in both these bands, with Mike Rutherford later commenting, "Pete was—and still is, I think—a frustrated drummer."[26]

Career

[edit]1965–1975: Early career and Genesis

[edit]In 1965, while still at Charterhouse, Gabriel formed the band Garden Wall with his schoolmates Tony Banks on piano, Johnny Trapman on trumpet, and Chris Stewart on drums.[25] Banks had started at Charterhouse at the same time as Gabriel, and the two were uninterested in school activities but bonded over music and started to write songs. At their final concert before they broke up, Gabriel wore a kaftan and beads and showered the audience with petals he had picked from neighbouring gardens.[23] Garden Wall disbanded in 1967; Gabriel and Banks were invited by their Charterhouse schoolmates Anthony Phillips and Mike Rutherford, who were in their own band at the school called Anon until it split up the previous year, to work on a demo tape of songs together.[27] Gabriel and Banks contributed "She Is Beautiful", the first song they wrote together. The tape was sent to Charterhouse alumni, musician Jonathan King, who was immediately enthusiastic largely due to Gabriel's vocals. He signed the group and suggested that their name be Gabriel's Angels, but this was unpopular with the other members, and they soon settled on his other suggestion of Genesis.

After King suggested they stick to more straightforward pop, Gabriel and Banks wrote "The Silent Sun" as a pastiche of the Bee Gees, one of King's favourite bands. It became Genesis' first single, released in 1968,[28] and was included on their debut studio album From Genesis to Revelation (1968). Following the commercial failure of From Genesis to Revelation, the band went their separate ways, and Gabriel continued his studies at Charterhouse.[29] In September 1969, Gabriel, Banks, Rutherford, and Phillips decided to drop their plans and make Genesis a full-time band. In early 1970, Gabriel played the flute on Mona Bone Jakon by Cat Stevens. The second studio album by Genesis, Trespass (1970), marked Gabriel expanding his musical output with the flute, accordion, tambourine, and bass drum, and incorporating his soul music influences. Gabriel explained that he was driven to play these instruments because he was uncomfortable with doing nothing during instrumental sections.[30] He would have preferred to play keyboard instruments, but said, "[Banks] was extraordinarily possessive about the keyboards. I'd done a bit of flute at school, I always liked the sound, and a little bit of oboe (I was an even worse oboe player, but it made a couple of good noises now and again). Then the bass drum was something physical, visual, that I could kick hard and occasionally it was in time!"[31] The album sold few copies, with Gabriel at one point securing a place to study at the London School of Film Technique because the band "seemed to be dying".[32]

Genesis soon recruited guitarist Steve Hackett and drummer Phil Collins.[33] Gabriel began growing in confidence as a frontman; during an encore performance of "The Knife" on 19 June 1971, he took a running jump into the audience and expected them to catch him, only for them to instead move out of the way and leave him to land on the floor and break his ankle. He consequently had to perform Genesis' next several shows with a wheelchair and crutches.[34] Also during the Trespass tour, he started to recite stories to introduce songs as a way to cover the silence while the band tuned their instruments or technical faults were being fixed.[35] These stories were all improvised on the spot, and evolved as the tour went along.[30] The opener of their next studio album, Nursery Cryme (1971), "The Musical Box", was their first song in which Gabriel incorporated a story and characters into the lyrics, as the lyrics to previous story-based Genesis songs such as "White Mountain" and "One-Eyed Hound" were all written by other members of the group.[citation needed] Gabriel was the primary writer of "Harold the Barrel", another story song on Nursery Cryme, with Collins helping him on the lyrics.[36]

The shows featuring Foxtrot (1972) marked a key development in Gabriel's stage performance. During a gig in Dublin in September 1972, he disappeared from the set during the instrumental section of "The Musical Box" and reappeared in his wife's red dress and a fox's head, mimicking the album's cover. The idea of the fox costume had been suggested to him by Paul Conroy and Glen Colson, employees of Genesis's record label, Charisma Records.[37] Gabriel said he consulted the rest of Genesis about the fox costume but grew tired of arguing about it, but the other members all maintained that nothing was said about it beforehand and that when Gabriel came out in costume they initially mistook him for a fan invading the stage.[38] The incident received front-page coverage in Melody Maker, giving them national exposure which allowed the group to double their performance fee.[citation needed] One of Gabriel's stories was printed on the liner notes of their live album, Genesis Live (1973). By late 1973, following the success of Selling England by the Pound (1973), which centred on English themes and literary and materialistic references, a typical Genesis show had Gabriel wear fluorescent make-up, a cape, and bat wings for "Watcher of the Skies", a helmet, chest plate, and a shield for "Dancing with the Moonlit Knight", a crown of thorns and a flower mask for "Supper's Ready", and an old man mask for "The Musical Box".[39]

Gabriel continued to fight for involvement with Genesis's keyboards throughout his time with the group, and following a lengthy argument with Banks, he was allowed to play a minor keyboard part on "I Know What I Like (In Your Wardrobe)", only for this part to be left out of the mix.[40] "I Know What I Like" became Genesis's first hit single, reaching number 21 in the UK Singles Chart.[41]

The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974) was Gabriel's final studio album with Genesis. He devised its story of the spiritual journey of Rael, a Puerto Rican youth living in New York City, and insisted upon writing all the lyrics himself, whereas on previous albums the lyrics had been divided among all the members of Genesis.[42] Tensions increased during this period, and Gabriel split with the band to pursue a film project with William Friedkin, only to rejoin a week later.[26] Matters were complicated further with the difficult birth of Gabriel's first daughter, resulting in periods of time away from the band. The other members complained that Gabriel was showing a lack of commitment to the band. Gabriel saw this as a "really unsympathetic handling of my dealing with a family crisis" and said it caused a breakdown in his relationships with the rest of Genesis; Rutherford later admitted that they had been overly fixated on their music and were very unhelpful in what must have been a difficult time for Gabriel.[43] Gabriel was late to deliver the lyrics, but has denied that he was too busy to write much music for the album and relied on contributions from Banks and Rutherford.[44] Banks corroborated that Gabriel was the primary composer of the Lamb songs "The Carpet Crawlers" and "The Chamber of 32 Doors" and the sole composer of "Counting Out Time".[45]

During a stop in Cleveland, Ohio, early into the album's tour, Gabriel informed the band of his intention to leave at its conclusion.[46][47] Rutherford recalled that they all "could see it coming."[26] Music critics often focused their reviews on Gabriel's theatrics and took the band's musical performance as secondary, which irritated the rest of the band.[48] The tour ended in May 1975, after which Gabriel wrote a piece for the press on 15 August, entitled "Out, Angels Out", about his departure, his disillusion with the business, and his desire to spend time with his family.[49] The news stunned fans of the group and left commentators wondering if the band could survive without him.[50][51] His exit resulted in drummer Phil Collins reluctantly taking over on lead vocals after 400 singers were fruitlessly auditioned.

1975–1985: Solo debut with four self-titled albums

[edit]Gabriel described his break from the music business as his "learning period", during which he took piano and music lessons. He had recorded demos by the end of 1975, the fruits of a period of writing around 20 songs with his friend Martin Hall.[52] After preparing material for a studio album Gabriel recorded his solo debut, Peter Gabriel, in 1976 and 1977 in Toronto and London, with producer Bob Ezrin.

Gabriel did not title his first four studio albums. All were labelled Peter Gabriel, using the same typeface, with designs by Hipgnosis. "The idea is to do it like a magazine, which will only come out once a year," he remarked in 1978. "So it's the same title, the same lettering in the same place; only the photo is different."[53] Each album has, however, been given a nickname by fans, usually relating to the album cover.

Peter Gabriel (a.k.a. Peter Gabriel 1: Car) was released in February 1977 and reached No. 7 in the UK and No. 38 in the US. Its lead single, "Solsbury Hill", is an autobiographical song about a spiritual experience on top of Solsbury Hill in Somerset. "It's about being prepared to lose what you have for what you might get ..." said Gabriel. "It's about letting go."[54] Gabriel toured the album with an 80-date tour from March to November 1977 with a band that included guitarist Robert Fripp of King Crimson often playing off stage and introduced as "Dusty Rhodes".[55]

In late 1977, Gabriel started recording the second Peter Gabriel studio album (a.k.a. Peter Gabriel 2: Scratch) in the Netherlands, with Fripp as producer. Its "Mother of Violence" was written by Gabriel and his first wife Jill. Released in June 1978, the album went to No. 10 in the UK and No. 45 in the US. Gabriel's tour for the album lasted from August to December 1978. On this tour, Gabriel and his band shaved their heads.

Gabriel recorded the third Peter Gabriel studio album (a.k.a. Peter Gabriel 3: Melt) in England in 1979. He developed an interest in African music and drum machines and later hailed the record as his artistic breakthrough. Gabriel banned the use of cymbals on the album in order to grant more sonic space for instruments like keyboards and synths. This resulted in the creation of the distinctive gated reverb,[56] a noise processing technique which came about while recording drums on "Intruder", one of the tracks featuring Phil Collins. Collins implemented the reverb to great effect on his debut solo single "In the Air Tonight" and it has since became a signature sound of the 1980s and beyond.

Upon completion Atlantic Records, Gabriel's US distributor who had released his first two albums, refused to put out Peter Gabriel 3: Melt as they thought it was not commercial enough. Gabriel signed a recording contract with Mercury Records.[57] Released in May 1980, the album went to No. 1 in the UK for three weeks. In the US, it peaked at No. 22. The single "Games Without Frontiers" went to No. 4 and "Biko" went to No. 36 in the UK. After a handful of shows in 1979, Gabriel toured the album from February to October 1980. The tour marked Gabriel's first successful instance of crowd surfing (following his failed June 1971 attempt when touring with Genesis) when he fell back into the audience in a crucifix position. The stunt became a staple of his live shows.[57][58]

On Peter Gabriel four (a.k.a. Peter Gabriel 4: Security), Gabriel took on greater responsibility over the production than before. He recorded it in 1981 and 1982, solely on digital tape, with a mobile studio parked at his home, Ashcombe House, in Somerset. Gabriel utilized a Fairlight CMI digital sampling synthesizer and incorporated electronic instrumentation with sampling world beat percussion. "Over the course of the last two albums," he observed, "I've got back into a rhythm consciousness. And the writing—particularly with the invention of these drum machines—is fantastic. You can store in their memories rhythms that interest you and excite you. And then the groove will carry on without you, and the groove will be exactly what you want it to be, rather than what a drummer thinks is appropriate for what you're doing."[22]

The fourth Peter Gabriel, released in September 1982, hit No. 6 in the UK and No. 28 in the US. The second single, "Shock the Monkey", became Gabriel's first top 40 hit in the US, reaching No. 29. To handle American distribution, Gabriel signed with Geffen Records, which—initially unbeknown to Gabriel—titled the album Security to differentiate it from the first three. Gabriel's 1982 tour lasted a year and became his first to make a profit.[59] Recordings from the tour were released on Gabriel's debut live release, Plays Live (1983).

Gabriel produced versions of the third and fourth Peter Gabriel albums with German lyrics. The third consisted of the studio recordings, overdubbed with new vocals. The fourth was remixed, with several tracks extended or altered.

In 1983, Gabriel developed the soundtrack for Alan Parker's drama film Birdy (1984), co-produced with Daniel Lanois. This consisted of new material, without lyrics, as well as remixed instrumentals from his previous studio album.

1985–1997: So and Us

[edit]After finishing the soundtrack to Birdy, Gabriel shifted his musical focus from rhythm and texture, as heard on Peter Gabriel four and Birdy, towards more straightforward songs.[59] In 1985, he recorded his fifth studio album, So (also co-produced with Lanois).[60] So was released in May 1986 and reached No. 1 in the UK and No. 2 in the US. It remains Gabriel's best-selling album with over five million copies sold in the US alone.[61][62] It produced one of Gabriel's signature songs, that has become a concert staple: In Your Eyes, with a distinctive vocal appearance by Youssou N'Dour, and three UK top 20 singles: "Sledgehammer", "Big Time" and "Don't Give Up", a duet with Kate Bush.[63]

The first went to No. 1 on the US Billboard Hot 100, Gabriel's only single of his career to do so. It knocked "Invisible Touch" by Genesis, his former band, out of the top spot, which was also their only US number one hit. In the UK, the single went to No. 4.[64] In 1990, Rolling Stone ranked So at No. 14 on its list of "Top 100 Albums of the Eighties".[65]

"Sledgehammer" was particularly successful, dealing with sex and sexual relations through lyrical innuendos. Its famed music video was a collaboration between director Stephen R. Johnson, Aardman Animations,[2] and the Brothers Quay and won a record nine MTV Video Music Awards in 1987.[2] In 1998, it was named MTV's number one animated video of all time.[66] So earned Gabriel two wins at the 1987 Brit Awards for Best British Male Solo Artist and Best British Video (for "Sledgehammer").[6] He was nominated for four Grammy Awards: Best Male Rock Vocal Performance, Song of the Year, and Record of the Year for "Sledgehammer", and Album of the Year for So.[67] Gabriel toured worldwide to support So with the This Way Up Tour, from November 1986 to October 1987.

In 1988, Gabriel became involved as composer for Martin Scorsese's film The Last Temptation of Christ (1988). Scorsese had contacted Gabriel about the project since 1983 and wished, according to Gabriel, to present "the struggle between the humanity and divinity of Christ in a powerful and original way".[68] Gabriel used musicians from WOMAD to perform instrumental pieces with focus on rhythm and African, Middle Eastern and European textures, using the National Sound Archive in London for additional inspiration.[68] The initial plan had dedicated ten weeks for recording before it was cut to three, leaving Gabriel unable to finish all the pieces he originally wanted to record.[68] When the film was finished, Gabriel worked on the soundtrack for an additional four months to develop more of his unfinished ideas. Its soundtrack was released as Passion in June 1989. It won Gabriel a Grammy Award for Best New Age Performance and a nomination for a Golden Globe for Best Original Score – Motion Picture. In 1990, Gabriel put out his first compilation album, Shaking the Tree: Sixteen Golden Greats, which sold 2 million copies in the US.

Up until 1989, Gabriel was managed by Gail Colson.[69] From 1989 to 1992, Gabriel recorded his follow-up to So, titled Us. The album saw Gabriel address personal themes, including his failed first marriage, psychotherapy, and the growing distance between him and his eldest daughter at the time.

Gabriel's introspection within the context of the album Us can be seen in the first single release "Digging in the Dirt" directed by John Downer. Accompanied by a video featuring Gabriel covered in snails and various foliage, this song made reference to the psychotherapy which had taken up much of Gabriel's time since the previous studio album. Gabriel describes his struggle to get through to his daughter in "Come Talk to Me" directed by Matt Mahurin, which featured backing vocals by Sinéad O'Connor. O'Connor also lent vocals to "Blood of Eden", directed by Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson, the third single to be released from the album, and once again dealing with relationship struggles, this time going right back to Adam's rib for inspiration.

The album is one of Gabriel's most personal. It met with less success than So, reaching No. 2 in the album chart on both sides of the Atlantic, and making modest chart impact with the singles "Digging in the Dirt" and the funkier "Steam", which evoked memories of "Sledgehammer". Gabriel followed the release of the album with the Secret World Tour, first using touring keyboardist Joy Askew to sing O'Connor's part, then O'Connor herself for a few months.[70] O'Connor quit the tour, and was replaced by Paula Cole, the latter appearing on the tour recordings: a double album Secret World Live, and a concert video also called Secret World Live, both released in 1994.[71] The film received the 1996 Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video, naming director Francois Girard and producer Robert Warr.[72]

Gabriel employed an innovative approach in the marketing of the Us album. Not wishing to feature only images of himself, he asked artist filmmakers Nichola Bruce and Michael Coulson to co-ordinate a marketing campaign using contemporary artists. Artists such as Helen Chadwick, Rebecca Horn, Nils-Udo, Andy Goldsworthy, David Mach and Yayoi Kusama collaborated to create original artworks for each song on the multi-million-selling CD. Coulson and Bruce documented the process on Hi-8 video. Bruce left Real World and Coulson continued with the campaign, using the documentary background material as the basis for a promotional EPK, the long-form video All About Us and the interactive CD-ROM Xplora1: Peter Gabriel's Secret World.

Gabriel won three more Grammy Awards, all in the Music Video category. He won the Grammy Award for Best Short Form Music Video in 1993 and 1994 for the videos to "Digging in the Dirt" and "Steam", respectively. Gabriel also won the 1996 Grammy Award for Best Long Form Music Video for his Secret World Live video.

1997–2009: OVO and Up

[edit]In 1997, Gabriel was invited to participate in the direction and soundtrack of the Millennium Dome Show, a live multimedia performance staged in the Millennium Dome in London throughout 2000.[73] Gabriel said the team were given free rein, which contributed to the various problems they encountered with it, such as a lack of proper budgeting. He also felt that management, while succeeding to get the building finished on time, failed to understand the artistic side of the show and its content.[74] Gabriel's soundtrack was released as OVO in June 2000. The Story of OVO was released in the CD-booklet-shaped comic book which was part of the CD edition with the title "OVO The Millennium Show".[75]

Around that same time, the Genesis greatest hits album, Turn It On Again: The Hits (1999), featured Gabriel sharing vocals with Phil Collins on a new version of "The Carpet Crawlers" entitled "The Carpet Crawlers 1999", produced by Trevor Horn.

In 2002 he stuck with soundtrack work for his next project, scoring for the Australian film Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002) with worldbeat music. Released in June 2002, Long Walk Home: Music from the Rabbit-Proof Fence received a Golden Globe Award nomination for Best Original Score – Motion Picture.

Later in 2002, Up, Gabriel's first full-length studio album in a decade, was released in September 2002. He started work on it in 1995 before production halted three years later to focus time on other projects and collaborations. Work resumed in 2000, by which time Gabriel had 130 potential songs for the album, and spent almost two years on it before management at Virgin Records pushed Gabriel to complete it.[76] Up reached No. 9 in the US and No. 11 in the UK, and supported with a world tour with a band that included Gabriel's daughter Melanie on backing vocals. The tour was documented with two live DVDs: Growing Up Live (2003) and Still Growing Up: Live & Unwrapped (2005).

In 2004, Gabriel met with his former Genesis bandmates to discuss the possibility of staging The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway (1974) as a reunion tour. He ultimately dismissed the idea, paving the way for Banks, Rutherford and Collins to organise the Turn It On Again: The Tour. Gabriel produced and performed at the Eden Project Live 8 concert in July 2005. He joined Cat Stevens on stage to perform "Wild World" during Nelson Mandela's 46664 concert. In 2005, FIFA asked Gabriel and Brian Eno to organise an opening ceremony for the 2006 FIFA World Cup in Germany, but FIFA cancelled the idea in January 2006. At the opening ceremony of the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin, Gabriel performed John Lennon's "Imagine".[77]

In November 2006, the Seventh World Summit of Nobel Peace Laureates in Rome presented Gabriel with the Man of Peace award. The award, presented by former General Secretary of the USSR and Nobel Peace Prize winner Mikhail Gorbachev and Walter Veltroni, Mayor of Rome, was an acknowledgement of Gabriel's extensive contribution and work on behalf of human rights and peace. The award was presented in the Giulio Cesare Hall of the Campidoglio in Rome. At the end of the year, he was awarded the Q magazine Lifetime Achievement Award, presented to him by American musician Moby. In an interview published in the magazine to accompany the award, Gabriel's contribution to music was described as "vast and enduring."

Gabriel took on a project with the BBC World Service's competition "The Next Big Thing" to find the world's best young band. Gabriel judged the final six young artists with William Orbit, Geoff Travis and Angélique Kidjo.

In June 2008, Gabriel released Big Blue Ball, an album of various artists collaborating with each other at his Real World Studios across three summers in the 1990s. He planned its release in the US without assistance from a label; he raised £2 million towards the recording and distribution of the album with Ingenious Media with the worldwide release handled through Warner Bros. Records.[78] Gabriel appeared on a nationwide tour for the album in 2009.[79]

Gabriel was a judge for the 6th and 8th annual Independent Music Awards to support independent artists.[80]

Gabriel contributed to the Pixar film WALL-E soundtrack in 2008 with Thomas Newman, including the film's closing song, "Down to Earth", for which they received the Grammy Award for Best Song Written for a Motion Picture, Television or Other Visual Media. The song was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song and an Academy Award for Best Original Song. In February 2009, Gabriel announced that he would not be performing on the 2008 Academy Awards telecast because producers of the show were limiting his performance of "Down to Earth" from WALL-E to 90 seconds. According to Gabriel, his window was reduced to 65 seconds. John Legend and the Soweto Gospel Choir performed the song in his stead.[81]

Gabriel's 2009 tour appearances included Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Peru and Venezuela. His first ever performance in Peru was held in Lima on 20 March 2009, during his second visit to the country.

On 25 July 2009, he played at WOMAD Charlton Park, his only European performance of the year, to promote Witness. The show included two tracks from the then-forthcoming Scratch My Back: Paul Simon's "The Boy in the Bubble" and the Magnetic Fields' "The Book of Love".[82]

2009–2019: Scratch My Back, New Blood and further side projects

[edit]

In 2009, Gabriel recorded Scratch My Back, an album of cover songs by various artists including David Bowie, Lou Reed, Arcade Fire, Radiohead, Regina Spektor and Neil Young. The original concept was for Gabriel to cover an artists' song if they, in turn, covered one of his for an album simultaneously released as I'll Scratch Yours, but several participants later declined or were late to deliver and it was placed on hold.[83] Gabriel avoided using drums and guitar in favour of orchestral arrangements, and altered his usual songwriting method by finishing the vocals first and then the song, for which he collaborated with John Metcalfe.[84] Released in February 2010, Scratch My Back reached No. 12 in the UK. Gabriel toured worldwide with the New Blood Tour from March 2010 to July 2012 with a 54-piece orchestra and his daughter Melanie and Norwegian singer-songwriter Ane Brun on backing vocals. The follow-up, And I'll Scratch Yours, was released in September 2013.

During the New Blood Tour, Gabriel decided to expand on the Scratch My Back concept and, with Metcalfe's assistance, re-record a collection of his own songs with an orchestra. The result, New Blood, was released in October 2011.[85]

In September 2012, Gabriel kicked off his Back to Front Tour which featured So (1986) performed in its entirety with the original musicians who played on the album, to mark its 25th anniversary.[86] When the opening leg finished a month later, Gabriel took one year off to travel the world with his children.[87][88] The tour resumed with a European leg from September 2013 to December 2014.[89]

In 2014, Gabriel was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist by Coldplay frontman Chris Martin. They performed Gabriel's "Washing of the Water" together. Gabriel performed "Heroes" by David Bowie with an orchestra at a concert in Berlin to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall in November 2014.

In 2016, he was featured on the song "A.I." by American pop rock band OneRepublic from their fourth studio album Oh My My.[90][91][92]

In June 2016, Gabriel released the single "I'm Amazing". The song was written several years prior, in part as a tribute to boxer Muhammad Ali.[93] That month, he embarked on a joint tour with Sting titled The Rock Paper Scissors North American Tour.[94]

Gabriel re-emerged in 2019 with the release of Rated PG, a compilation of songs that were created for film soundtracks throughout his career. The song selection spans over 30 years and includes tracks that had never been released on an official Gabriel album previously, including "Down to Earth" (from WALL-E) and "That'll Do" (from Babe: Pig in the City), an Oscar-nominated collaboration with Randy Newman. Initially only released on vinyl for Record Store Day on 13 April, the album was eventually released on digital streaming services later that month.[95] Later that same year, Gabriel issued another digital release on 13 September titled Flotsam and Jetsam, a collection of B-sides, remixes and rarities that span Gabriel's entire solo career from 1976 to 2016, including his first solo recording, a cover of the Beatles' song "Strawberry Fields Forever".[96]

2022–present: I/O and possible follow-up album

[edit]By 2002, Gabriel had been continually working on what he had given the tentative title of I/O, his tenth studio album, which he had begun work on as early as 1995.[97][98] It was originally set to be released 18 months after Up, but touring pushed the release far away.[99] He did an interview with Rolling Stone in 2005 stating that he had 150 songs in various stages.[100] From 2013 to 2016, he posted regularly on social media about recording the new album.[101] In 2019, he spoke on BBC Radio 6 about how he had taken a hiatus from making music due to his wife being sick, but he had begun to return to it now that she had recovered.[102] In 2021, he was interviewed multiple times about his new album, and revealed that he had been recording with Manu Katché, Tony Levin and David Rhodes on 17 new songs.[103][104] He posted multiple photos to his Facebook and Instagram of these sessions.[105][106] In June 2022, Katché told the French magazine L'Illustré that the album was nearly complete and would be released later that year, pending an official announcement.[107][108][109]

In November 2022, Gabriel announced his upcoming "I/O The Tour" for the spring of 2023 across several European cities, with later dates to be confirmed for the North America leg of the tour for the late summer/fall of 2023.[110] This announcement also confirmed the name of the upcoming album to be stylised as I/O. The first single from the album, "Panopticom", was released digitally on 6 January 2023.[111] A new piece from the album will be released on the date of each full moon in 2023,[112] as well as a different mix of the song on each new moon in 2023, starting with the Dark Side Mix of "Panopticom".[113] On 5 February, Gabriel released "The Court", the second single from the album. On 7 March, Gabriel released the third single, "Playing for Time". A basic arrangement of the song featuring only Gabriel on piano and Levin on bass had already opened the shows on the Back to Front Tour, by the name of "Daddy Long Legs".[114][115] The title track "I/O" was the fourth single released on 6 April. On 5 May, Peter Gabriel released the fifth single from the album, "Four Kinds of Horses", a track which is a collaboration with Brian Eno and Richard Russell. The sixth single, "Road to Joy", was released on 4 June. Six more singles were released, separately, within the next six months—"So Much", "Olive Tree", "Love Can Heal", "This Is Home", "And Still" and "Live and Let Live"—before I/O was finally released on 1 December 2023.[116]

One day prior to I/O's release, Gabriel told The New York Times that he does not expect a follow-up album (which he described as his "brain project") to take another 21 years, saying that "there's a lot of stuff in the can" but added that the material is not yet finished.[117]

Additionally, Gabriel stated in his November 2023 Full Moon update video that the track "What Lies Ahead" will be on "the next record".[118] He performed "What Lies Ahead" several times in 2023 and it was a contender for I/O.

Artistry

[edit]Stylistically, Gabriel's music has been alternately described by music writers as progressive rock,[1] art rock,[119] art pop,[120] worldbeat,[121] post-progressive[122] and progressive soul.[123] According to Rolling Stone journalist Ryan Reed, Gabriel has developed in all as an "art-rock innovator, soul-pop craftsman, [and] 'world music' ambassador" over the course of his career,[124] while music scholar Gregg Akkermann argues that, despite his progressive rock origins, he has "managed to attract fans from across the spectrum: prog rock, alternative rock, world beat, blue-eyed soul, dance music, the college crowd, the teens, Americans and Europeans".[125] More broadly, AllMusic's Stephen Thomas Erlewine says Gabriel emerged during the 1980s as "one of rock's most ambitious, innovative musicians", as well as "an international pop star".[126]

Gabriel has worked with a relatively stable crew of musicians and recording engineers throughout his solo career. Bass and Stick player Tony Levin has performed on every Gabriel studio album and every live tour except for Scratch My Back (2010), the soundtracks Passion (1989) and Long Walk Home (2002), and the New Blood Tour. Guitarist David Rhodes has been Gabriel's guitarist of choice since 1979. Prior to So (1986), Jerry Marotta was Gabriel's preferred drummer, both in the studio and on the road. (For the So and Us albums and tours Marotta was replaced by Manu Katché, who was then replaced by Ged Lynch on parts of the Up album and all of the subsequent tour). Gabriel is known for choosing top-flight collaborators, from co-producers such as Ezrin, Fripp, Lillywhite and Lanois to musicians such as Natalie Merchant, Elizabeth Fraser, L. Shankar, Trent Reznor, Youssou N'Dour, Larry Fast, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan, Sinéad O'Connor, Kate Bush, Ane Brun, Paula Cole, John Giblin, Dave Gregory, Peter Hammill, Papa Wemba, Manu Katché, Bayete, Milton Nascimento, Phil Collins, Stewart Copeland and OneRepublic.

Over the years, Gabriel has collaborated with singer Kate Bush several times; Bush provided backing vocals for Gabriel's "Games Without Frontiers" and "No Self Control" in 1980, and female lead vocal for "Don't Give Up" (a top 10 hit in the UK) in 1986, and Gabriel appeared on her television special. Their duet of Roy Harper's "Another Day" was discussed for release as a single, but never appeared.[127]

He also collaborated with avant-garde artist Laurie Anderson on two versions of her composition "Excellent Birds"—one for her second album Mister Heartbreak (1984),[128] and another version called "This is the Picture (Excellent Birds)", which appeared on cassette and CD versions of So.

Gabriel sang (along with Jim Kerr of Simple Minds) on "Everywhere I Go", from the Call's 1986 studio album, Reconciled. On Toni Childs' 1994 studio album, The Woman's Boat, Gabriel sang on the track, "I Met a Man".[129]

In 1998, Gabriel appeared on the soundtrack of Babe: Pig in the City as the lead vocalist of the song "That'll Do", written by Randy Newman. The song was nominated for an Academy Award, and Gabriel and Newman performed it at the following year's Oscar telecast. He performed a similar soundtrack appearance for the 2004 film Shall We Dance?, singing a cover version of "The Book of Love" by the Magnetic Fields.

In 1987, Gabriel appeared on Robbie Robertson's self-titled solo studio album, singing on "Fallen Angel"; co-wrote two Tom Robinson singles; and appeared on Joni Mitchell's 1988 studio album Chalk Mark in a Rain Storm, on the opening track "My Secret Place".

In 2001, Gabriel contributed lead vocals to the song "When You're Falling" on Afro Celt Sound System's Volume 3: Further in Time.[130] In the summer of 2003, Gabriel performed in Ohio with a guest performance by Uzbek singer Sevara Nazarkhan.

Gabriel collaborated on tracks with electronic musician BT, who also worked on the OVO soundtrack with him. The tracks were never released, as the computers they were contained on were stolen from BT's home in California. He also sang the lyrics for Deep Forest on their theme song for the movie Strange Days (1995). In addition, Gabriel has appeared on Angelique Kidjo's 2007 studio album Djin Djin, singing on the song "Salala".

Gabriel has recorded a cover of the Vampire Weekend single "Cape Cod Kwassa Kwassa" with Hot Chip, where his name is mentioned several times in the chorus. He substitutes the original line "But this feels so unnatural / Peter Gabriel too / This feels so unnatural/ Peter Gabriel too" with "It feels so unnatural / Peter Gabriel too / and it feels so unnatural / to sing your own name."[131]

Gabriel collaborated with Arcade Fire on their 2022 studio album, We. He sang backing vocals on the track "Unconditional II (Race and Religion)".[132]

WOMAD and other projects

[edit]Gabriel's interest in world music was first apparent on his third solo studio album. According to Spencer Kornhaber in The Atlantic in 2019: "When Peter Gabriel moved toward 'world music' four decades ago, he not only evangelized sounds that were novel to Western pop. He also set a radio template: majestic, with flourishes meant to read as 'exotic,' and lyrics meant to change lives."[133] This influence has increased over time, and he is the driving force behind the World of Music, Arts and Dance (WOMAD) movement. Gabriel said:

The first time I really got into music from another culture was as a result of the shifting of Radio 4, which I used to wake up to. I'd lost it on medium wave and was groping around in the morning on the dial, trying to find something that I could listen to, and came across a Dutch radio station who were playing the soundtrack from some obscure Stanley Baker movie called Dingaka. That had quite a lot of stuff from—I think it was—Ghana. I can't remember now, but it really moved me. One of the songs I heard on that was a thing called 'Shosholoza', which I recorded on the b-side of the 'Biko' single.[134]

Gabriel created the Real World Studios and record label to facilitate the creation and distribution of such music by various artists, and he has worked to educate Western culture about such musicians as Yungchen Lhamo, Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan and Youssou N'dour.

He has a longstanding interest in human rights and launched Witness,[135] a charity that trains human rights activists to use video and online technologies to expose human rights abuses. In 2006, his work with WITNESS and his long-standing support of peace and human rights causes was recognised by the Nobel Peace Prize Laureates with the Man of Peace award.

In the 1990s, with Steve Nelson of Brilliant Media and director Michael Coulson, he developed advanced multimedia CD-ROM-based entertainment projects, creating Xplora (the world's largest-selling music CD-ROM), and subsequently the EVE CD-ROM. EVE was a music and art adventure game directed by Michael Coulson and co-produced by the Starwave Corporation in Seattle; it won the Milia d'Or award Grand Prize at the Cannes in 1996.

In 1990, Gabriel lent his backing vocals to Ugandan political exile Geoffrey Oryema's "Land of Anaka", appearing on Oryema's first studio album Exile, released on Gabriel's Real World label.[136]

In 1994, Gabriel starred in Breck Eisner's short film Recon as a detective who enters the minds of murder victims to find their killer's identity.

Gabriel helped pioneer a new realm of musical interaction in 2001, visiting Georgia State University's Language Research Center to participate in keyboard jam sessions with bonobo apes from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (This experience inspired the song "Animal Nation", which was performed on Gabriel's 2002 "Growing Up" tour and was featured on the Growing Up Live DVD and The Wild Thornberrys Movie soundtrack.) Gabriel's desire to bring attention to the intelligence of primates also took the form of ApeNet, a project that aimed to link great apes through the internet, enabling the first interspecies internet communication.[137]

He was one of the founders of on Demand Distribution (OD2), one of the first online music download services. Prior to its closure in 2009, its technology had been used by over 100 music download sites including MSN Music UK, MyCokeMusic, Planet Internet (KPN), Wanadoo and CD WOW!. OD2 was bought by US company Loudeye in June 2004 and subsequently by Finnish mobile giant Nokia in October 2006 for $60 million.[138]

Gabriel is co-founder (with Brian Eno) of a musicians union called Mudda, short for "magnificent union of digitally downloading artists."[139][140]

In 2000, Gabriel collaborated with Zucchero, Anggun and others in a charity for kids with AIDS. Erick Benzi wrote words and music and Patrick Bruel, Stephan Eicher, Faudel, Lokua Kanza, Laam, Nourith, Axelle Red have accepted to sing it.[141]

In 2003, Gabriel contributed a song for the video game Uru: Ages Beyond Myst.[142] In 2004, Gabriel contributed another song ("Curtains") and contributed voice work on another game in the Myst franchise, Myst IV: Revelation.[143]

In June 2005, Gabriel and broadcast industry entrepreneur David Engelke purchased Solid State Logic, a manufacturer of mixing consoles and digital audio workstations.[144] In 2017, the company was sold to the Audiotonix Group.[145]

In May 2008, Gabriel's Real World Studios, in partnership with Bowers & Wilkins, started the Bowers & Wilkins Music Club—later known as Society of Sound—a subscription-based music retail site. Albums are currently available in either Apple Lossless or FLAC format.[146]

He is one of the founding supporters of the annual global event Asteroid Day.[147]

Activist for humanitarian causes

[edit]In 1986, he started what has become a longstanding association with Amnesty International, becoming a pioneering participant in all 28 of Amnesty's Human rights concerts—a series of music events and tours staged by the US Section of Amnesty International between 1986 and 1998. He performed during the six-concert A Conspiracy of Hope US tour in June 1986; the twenty-concert Human Rights Now! world tour in 1988; the Chile: Embrace of Hope Concert in 1990 and at The Paris Concert for Amnesty International in 1998. He also performed in Amnesty's Secret Policeman's Ball benefit shows in collaboration with other artists and friends such as Lou Reed, David Gilmour of Pink Floyd and Youssou N'Dour; Gabriel closed those concerts performing his anti-apartheid anthem "Biko".[148] He spoke of his support for Amnesty on NBC's Today Show in 1986.[149]

Inspired by the social activism he encountered in his work with Amnesty, in 1992, Gabriel co-founded WITNESS, a non-profit organisation that equips, trains and supports locally based organisations worldwide to use video and the internet in human rights documentation and advocacy.

In 1995, Gabriel and Cape Verdean human rights activist Vera Duarte were awarded the North–South Prize in its inaugural year.[150][151]

In the late 1990s, Gabriel and entrepreneur Richard Branson discussed with Nelson Mandela their idea of a small, dedicated group of leaders, working objectively and without any vested personal interest to solve difficult global conflicts.

On 18 July 2007, in Johannesburg, South Africa, Nelson Mandela announced the formation of a new group, The Elders, in a speech he delivered on the occasion of his 89th birthday. Kofi Annan served as Chair of the Elders and Gro Harlem Brundtland as deputy chair. The other members of the group are Martti Ahtisaari, Ela Bhatt, Lakhdar Brahimi, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, Jimmy Carter,[152] Hina Jilani, Graça Machel, Mary Robinson[152] and Ernesto Zedillo. Desmond Tutu was an Honorary Elder, as was Nelson Mandela. The Elders is independently funded by a group of donors, including Branson and Gabriel.

The Elders use their collective skills to catalyse peaceful resolutions to long-standing conflicts, articulate new approaches to global issues that are causing or may later cause immense human suffering, and share wisdom by helping to connect voices all over the world. They work together to consider carefully which specific issues to approach.

In November 2007, Gabriel's non-profit group WITNESS launched The Hub, a participatory media site for human rights.

In September 2008, Gabriel was named as the recipient of Amnesty International's 2008 Ambassador of Conscience Award. In the same month, he received Quadriga United We Care award of Werkstatt Deutschland along with Boris Tadić, Eckart Höfling and Wikipedia. The award was presented to him by Queen Silvia of Sweden.[153]

In 2010, Gabriel lent his support to the campaign to release Sakineh Mohammadi Ashtiani, an Iranian Azeri woman who was sentenced to death by stoning after being convicted of committing adultery.[154]

In December 2013, Gabriel posted a video message in tribute to the deceased former South African president and anti-apartheid leader Nelson Mandela. Gabriel was quoted:

To come out of 27 years in jail and to immediately set about building a Rainbow Nation with your sworn enemy is a unique and extraordinary example of courage and forgiveness. In this case, Mandela had seen many of his people beaten, imprisoned and murdered, yet he was still willing to trust the humanity and idealism of those who had been the oppressors, without whom he knew he could not achieve an almost peaceful transition of power. There is no other example of such inspirational leadership in my lifetime.[155][156]

Gabriel has criticised Air France for their continued transport of monkeys to laboratories. In a letter to the airline, Gabriel wrote that in laboratories, "primates are violently force-fed chemicals, inflicted with brain damage, crippled, addicted to cocaine or alcohol, deprived of food and water, or psychologically tormented and ultimately killed."[157]

In March 2014, Gabriel publicly supported #withsyria, a campaign to rally support for victims of the Syrian Civil War.[158]

In November 2014, Gabriel, along with Pussy Riot and Iron & Wine supported Hong Kong protesters at Hong Kong's Lennon Wall in their efforts.[159]

In March 2015, Gabriel was awarded an honorary doctorate by the University of South Australia in recognition of his commitment to creativity and its transformational power in building peace and understanding.[160]

He composed the song "The Veil" for Oliver Stone's film Snowden (2016).[161]

Political views

[edit]Gabriel has been described as one of rock's most political musicians by AllMusic.[15] In 1992, on the 20th anniversary of the Bloody Sunday massacre, Gabriel joined Peter Hain, Jeremy Corbyn, Tony Benn, Ken Loach, John Pilger and Adrian Mitchell in voicing his support for a demonstration in London calling for British withdrawal from Northern Ireland.[162]

At the 1997 general election, he declared his support for the Labour Party, which won that election by a landslide after 18 years out of power, led by Tony Blair.[163] In 1998, he was named in a list of the biggest private financial donors to Labour.[164] He subsequently distanced himself from the Labour government following Tony Blair's support for George W. Bush and Britain's involvement in the Iraq War, which he strongly opposed.[152] Gabriel later explained his decision for funding Labour, saying, "after all those years of Thatcher, that was the only time I've put money into a political party because I wanted to help get rid of the Tory government of that time."[165]

In 2005, Gabriel gave a Green Party of England and Wales general election candidate special permission to record a cover of his song "Don't Give Up" for his campaign.[166] In 2010, The Guardian described Gabriel as "a staunch advocate of proportional representation."[167] In 2013, he stated that he had become more interested in online petitioning organisations to effect change than traditional party politics.[152]

In 2012, Gabriel condemned the use of his music by the American conservative talk radio personality Rush Limbaugh during a controversial segment in which Limbaugh vilified Georgetown University law student Sandra Fluke. A statement on behalf of Gabriel read: "Peter was appalled to learn that his music was linked to Rush Limbaugh's extraordinary attack on Sandra Fluke. It is obvious from anyone that knows Peter's work that he would never approve such a use. He has asked his representatives to make sure his music is withdrawn and especially from these unfair, aggressive and ignorant comments."[168]

In 2016, Gabriel supported the UK's continued membership of the European Union in the referendum on the issue.[169]

Gabriel has declared his support for the two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. In 2014, he contributed songs to a new compilation album to raise funds for humanitarian organisations aiding Palestinian Arabs in Gaza. Gabriel was quoted: "I am certain that Israelis and Palestinians will both benefit from a two-state solution based on the 1967 borders. We have watched Palestinians suffer for too long, especially in Gaza. I am not, and never was, anti-Israeli or anti-Semitic, but I oppose the policy of the Israeli government, oppose injustice and oppose the occupation ... I am proud to be one of the voices asking the Israeli government: 'Where is the two-state solution that you wanted so much?' and clearly say that enough is enough."[170] In 2019, Gabriel was among 50 artists who urged the BBC to ask for the Eurovision Song Contest to be moved out of Israel, citing human rights concerns.[171] In 2023, Gabriel signed the Artists4Ceasefire open letter to President Joe Biden calling for a ceasefire during the Israeli bombardment of Gaza.[172]

Gabriel has been in support of the Armenian genocide recognition.[173] In October 2020, he posted a message on social media in support of Armenia and Artsakh in regards to the Nagorno-Karabakh war. He said, "The fighting that has now broken out between Azerbaijan and Armenia is really horrific and we need to lobby whoever we can to encourage a ceasefire, but hearing reports that President Erdoğan has now lined up 80,000 Turkish troops on the Armenian border is a terrifying prospect, full of the dark echoes of history."[174]

In popular culture

[edit]Gabriel's music featured prominently on the popular 1980s television show Miami Vice. The songs include "The Rhythm of the Heat" and "Biko" (from "Evan"), "Red Rain" (from "Stone's War"), "Mercy Street" (from "Killshot"), "Sledgehammer" (from "Better Living Through Chemistry"), "We Do What We're Told (Milgram's 37)" (from "Forgive Us Our Debts" and "Deliver Us from Evil") and "Don't Give Up" (from "Redemption in Blood"). With seven songs used total, Gabriel had the most music featured by a solo artist in the series, and he is the only artist to have had a song used in four of Vice's five seasons. Five of the nine tracks on his most popular album So (1986) were used in the series.

Gabriel’s song "In Your Eyes" features twice in the teen romance drama Say Anything (1989). It is the song playing on Lloyd Dobler’s boombox as he serenades Diane, creating the film’s most iconic scene.

Gabriel's cover of David Bowie's "Heroes" was featured in the fourth season finale of Big Love, as well as the first season and the ending scene of Stranger Things season 3 and the ending credits of Lone Survivor. The song also features in 'Children of Mars', a 2020 episode of the web series Star Trek: Short Treks.

A series of spoof documentaries about the fictitious rock star Brian Pern were based loosely on Gabriel.[175]

In 2021, Northern Irish post-punk band Invaderband released their second studio album entitled 'Peter Gabriel'.[176] The sleeve was a painting of Gabriel by Luke Haines.

Personal life

[edit]Gabriel has married twice and has four children. In 1971, at age 21, he married Jill Moore, daughter of Baron Philip Moore.[177] They had two daughters,[152] one of whom, Anna-Marie, is a filmmaker who filmed and directed Gabriel's live DVDs Growing Up on Tour: A Family Portrait (2003), Still Growing Up: Live & Unwrapped (2005) and some of his music videos. Melanie is a musician who had been a backing vocalist in her father's band in 2002–2011. Both daughters appear in the final sequence of the video for their father's song "Sledgehammer".

Gabriel's marriage became increasingly strained, culminating in Moore's affair with David Lord, the co-producer of Gabriel's fourth studio album. After the couple divorced in 1987, Gabriel fell into a period of depression and attended therapy sessions for six years.

For a time after his divorce, Gabriel lived with American actress Rosanna Arquette.[177] In 2021, Irish singer Sinéad O'Connor said that she maintained an on-and-off relationship with Gabriel in the wake of his divorce. She ended the relationship because of her frustration with his lack of commitment, which inspired her single "Thank You for Hearing Me".[178]

Gabriel married Meabh Flynn in 2002, with whom he has two sons.[83][177]

Gabriel has resided in Wiltshire for many years and runs Real World Studios from Box, Wiltshire. He previously lived in the Woolley Valley near Bath, Somerset. In 2010, he joined a campaign to stop agricultural development in the valley, which had also inspired his first solo single, "Solsbury Hill", in 1977.[179]

Discography

[edit]Studio albums

- Peter Gabriel (1977; known as Peter Gabriel 1 and Car)

- Peter Gabriel (1978; known as Peter Gabriel 2 and Scratch)

- Peter Gabriel (1980; known as Peter Gabriel 3 and Melt)

- Peter Gabriel (1982; known as Peter Gabriel 4 and Security)

- So (1986)

- Us (1992)

- Up (2002)

- Scratch My Back (2010)

- New Blood (2011)

- I/O (2023)

Soundtracks

- Birdy (1985)

- Passion (1989)

- OVO (2000)

- Long Walk Home (2002)

Awards and nominations

[edit]See also

[edit]- List of ambient music artists

- List of artists who reached number one in the United States

- List of artists who reached number one on the U.S. Dance Club Songs chart

- List of artists who reached number one on the U.S. Mainstream Rock chart

- List of best-selling music artists

- 24997 Petergabriel

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Hudak, Joseph. "Peter Gabriel Biography". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 14 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Levy, Glen (26 July 2011). "The 30 All-TIME Best Music Videos - Peter Gabriel, 'Sledgehammer' (1986)". Time. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2024.

- ^ a b "Peter Gabriel on 30 years of WOMAD – and mixing music with politics". The Guardian. 26 July 2012. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel on the digital revolution". Edition.cnn.com. 22 July 2004. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Nelson Mandela launches Elders to save world". Telegraph Online. London. 19 July 2007. Archived from the original on 9 January 2014. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- ^ a b "The BRITs 1987". Brits.co.uk. Archived from the original on 17 March 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Past Winners: Peter Gabriel". The GRAMMYs. Archived from the original on 20 July 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Lily Allen wins web music award". BBC News. 4 October 2006. Archived from the original on 2 November 2006. Retrieved 23 June 2013.

- ^ "Oldies are golden at the Q awards". The Guardian. 31 October 2006. Archived from the original on 26 September 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2014.

- ^ "Winehouse triumphs at Ivor awards". BBC News. 24 May 2007. Archived from the original on 5 October 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "Gabriel shares Polar Music Prize". BBC News. 12 May 2009. Archived from the original on 17 May 2009. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel Receives Top Honor at BMI London Awards". Bmi.com. 17 October 2007. Archived from the original on 6 March 2010. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel Receives 'Man Of Peace' Award". Gigwise.com. 18 November 2006. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ "The 2008 TIME 100: Peter Gabriel". Time. 12 May 2008. Archived from the original on 22 August 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ a b Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "Peter Gabriel Biography". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ^ "Abba receive Hall of Fame honour". BBC News. 16 March 2010. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 25 February 2014.

- ^ "Nirvana inducted to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". BBC News. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 11 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ a b Easlea 2018, p. 25.

- ^ Peter Gabriel - Full Moon Update October 2023, 28 October 2023, retrieved 29 October 2023

- ^ Barratt, Nick (24 November 2007). "Family detective: Peter Gabriel". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 2 July 2019. Retrieved 2 July 2019.

- ^ a b Easlea 2018, p. 26.

- ^ a b Capital Radio interview with Alan Freeman, broadcast October 1982; transcribed in Gabriel fanzine White Shadow (#3, pp12) by editor Fred Tomsett

- ^ a b Frame 1983, p. 23.

- ^ Easlea 2018, p. 34.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Neer, Dan (1985). Mike on Mike [interview LP], Atlantic Recording Corporation.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 17.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 17.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 22.

- ^ a b Giammetti 2020, p. 84.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 54.

- ^ Blake, Mark (December 2011). "Cash for questions: Peter Gabriel". Q. p. 46.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 43.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 83.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel: "You could feel the horror ..." – Uncut". Uncut.co.uk. 19 October 2012. Archived from the original on 23 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 104.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 155-157.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 157, 162.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 162, 203.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 197.

- ^ Genesis UK chart history, The Official Charts Company. Retrieved 13 October 2024.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 211-213.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 217-218.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 236.

- ^ Giammetti 2020, p. 225-228.

- ^ Genesis 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Saavedra, David (24 September 2024). "Greek mythology and oversized egos: The Genesis album that ended progressive rock". El Pais. Retrieved 8 October 2024.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Bowler & Dray 1992, p. 107.

- ^ Swanson, Dave (15 August 2013). "38 Years Ago: Peter Gabriel Leaves Genesis". Ultimateclassicrock.com. Archived from the original on 21 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Singh, Anita (16 June 2014). "Genesis back together after nearly 40 years". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2015.

- ^ Welch, Chris (6 December 1975). "Behind Peter Gabriel's mask". Melody Maker. pp. 8–9. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- ^ Best magazine, May 1978; translated in Gabriel fanzine White Shadow (#1, pp13) by editor Fred Tomsett

- ^ Easlea 2018, p. 203.

- ^ Charone, Barbara (16 April 1977). "The Lamb Stands Up". Sounds. Archived from the original on 18 October 2021. Retrieved 14 April 2024.

- ^ Flans, Robyn (1 May 2005). "Classic Tracks: Phil Collins' "In the Air Tonight"". Mix Online. Archived from the original on 17 March 2007.

- ^ a b Pond, Steve (29 January 1987). "Peter Gabriel Hits the Big Time". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Fielder, Hugh (8 March 1980). "On the road – The games people play". Sounds. p. 51. Archived from the original on 13 June 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ a b Hutchinson, John (July 1986). "Peter Gabriel: From Brideshead to Sunken Heads". Musician. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019 – via Rock's Backpages.

- ^ "So – Peter Gabriel (credits)". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 25 May 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "British album certifications – Peter Gabriel – So" Archived 21 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. British Phonographic Industry. Retrieved 12 December 2014. Enter Peter Gabriel in the field Search. Select Artist in the field Search by. Select album in the field By Format. Click Go

- ^ "American album certifications – Peter Gabriel – So". riaa.com. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Roberts, David (2006). British Hit Singles & Albums. London: Guinness World Records Limited

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2006). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits. Billboard Books

- ^ The 100 Greatest Albums of the 80s. Rolling Stone. Special Issue 1990. Retrieved 21 November 2011

- ^ "MTV. Top Ten Animated Videos Countdown. June 28, 1998". Outpost-daria.com. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "29th Grammy Awards – 1987". Rockonthenet.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ a b c Asregadoo, Ted (5 June 2015). "Revisiting Peter Gabriel's 'Passion' soundtrack". Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Perrone, Pierre (22 December 1999). "Market Leaders Pick Their Market Leader: Who's the manager on top of the rock? – Business – News – The Independent". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 8 July 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- ^ Zindler, Bernd (Autumn 1999). "Peter Gabriel Secret World Tour". Genesis News. Retrieved 20 March 2022.

- ^ "Revisiting His Weird and Wonderful Performance: 'Peter Gabriel: Secret World Live'". PopMatters. 11 September 2012. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- ^ "38th Annual Grammy Awards". Grammy. Retrieved 30 July 2024.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel – OVO". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 May 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Coldstream, John (27 May 2000). "We are afraid of artists". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Gabriel, Peter (2000). The Story of OVO. Peter Gabriel Ltd. ISBN 0-9520864-3-3.

- ^ Williamson, Nigel (19 September 2002). "Don't hurry, be happy". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 22 June 2019. Retrieved 22 June 2019.

- ^ Poggioli, Sylvia (10 February 2006). "Olympic Games Kick Off with Art, Fashion, Dance". NPR. Archived from the original on 19 July 2020. Retrieved 31 May 2019.

- ^ Durman, Paul. Gabriel deals a blow to the record business Archived 20 November 2020 at the Wayback Machine, The Times. 21 January 2007.

- ^ "Gabriel Calls on Venture Capitalists To Help Album Launch". Contactmusic.com. 24 January 2007. Archived from the original on 12 January 2009. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Past Judges". Independent Music Awards. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ^ Finke, Nikki (12 February 2009). "Peter Gabriel Pissed At Oscar Producers And Won't Perform At Academy Awards". Deadline. Retrieved 19 August 2023.

- ^ Dalton, Stephen (27 July 2009). "Womad 2009 at Charlton Park Wiltshire". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 20 November 2020. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ^ a b McNulty, Bernadette (12 September 2013). "Peter Gabriel, interview". Telegraph.co.uk. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (1 March 2010). "Peter Gabriel Says, 'I'll Sing Yours, You Sing Mine'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 June 2019. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ Doran, John (19 September 2011). "An Invasion of Privacy: Peter Gabriel Interviewed". The Quietus. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Peter Announces North American Tour 'Back To Front' To Celebrate 25th Anniversary of 'So'". Petergabriel.com. Archived from the original on 23 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Lynskey, Dorian (26 July 2012). "Peter Gabriel on 30 years of Womad – and mixing music with politics". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 19 April 2017. Retrieved 23 June 2019.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel To Take A Year Off | Rock News | News". Planet Rock. 5 September 2012. Archived from the original on 7 November 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ Greene, Andy (4 September 2012). "QA: Peter Gabriel Reflects on His 1986 Landmark Album 'So' | Music News". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 9 September 2012. Retrieved 16 September 2012.

- ^ "Nirvana to be elevated to Rock and Roll Hall of Fame". BBC News. 17 December 2013. Archived from the original on 12 April 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "Coldplay's Chris Martin performs with Peter Gabriel at Rock And Roll Hall of Fame ceremony". NME. 11 April 2014. Archived from the original on 14 April 2014. Retrieved 11 April 2014.

- ^ Oh My My by OneRepublic, 7 October 2016, archived from the original on 8 August 2019, retrieved 8 August 2019

- ^ "New Track – I'm Amazing". Petergabriel.com. Archived from the original on 8 October 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Peter and Sting Tour 2016". Petergabriel.com. Archived from the original on 25 September 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Rated PG getting digital release". Peter Gabriel. Archived from the original on 17 July 2020. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Digital Release for Flotsam and Jetsam". Peter Gabriel. Archived from the original on 15 October 2019. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ "Genesis News Com [it]: Peter Gabriel - The Making Of I/O". genesis-news.com. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Beaumont, Mark (28 November 2023). "Peter Gabriel, 'I/O' review: A return well worth waiting for". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ "Richard Chappell: Recording Peter Gabriel's Up". soundonsound.com. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Greene, Andy (2 October 2007). "Peter Gabriel Plugs In: Peter Gabriel : Rolling Stone". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 2 October 2007. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (9 July 2015). "Peter Gabriel Working on New Album". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "/ Peter Gabriel: Work on new songs continues ..." genesis-news.com. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "/ Peter Gabriel: New album "closer than you think"". genesis-news.com. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Peter Gabriel talks about the new album @ Santeria Toscana 31 Milan Italy, 22 October 2021, archived from the original on 11 December 2021, retrieved 3 November 2021

- ^ : "Peter Gabriel's Instagram photo: "Recording in the Big Room at @realworldstudios, late Sept/early Oct 2021. 📸 @yorktillyer"". Instagram. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel on Instagram: "A few familiar faces at the recent recording session @realworldstudios. @davidrhodesofficial @tonylevin @manukatche 📸 @yorktillyer"". Instagram. Archived from the original on 23 December 2021. Retrieved 3 November 2021.

- ^ Benitez-Eves, Tina (6 June 2022). "Peter Gabriel Set to Release New Album, His First in 20 Years, Tour in 2023". americansongwriter.com. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Ewing, Jerry (4 June 2022). "Is Peter Gabriel's new album finally going to be released?". loudersound.com. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Richards, Will (5 June 2022). "Peter Gabriel to release first new album in 20 years this year, according to drummer". NME. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ "I/O The Tour announced". PeterGabriel.com. Retrieved 8 November 2022.

- ^ Hussey, Allison (6 January 2023). "Peter Gabriel Shares New Song "Panopticom"". Pitchfork. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ Rapp, Allison (6 January 2023). "Peter Gabriel Will Release a New Song Each Full Moon". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ "The Dark-Side of Panopticom".

- ^ "Peter Gabriel - Daddy Long Legs (Back To Front– Live in London)". YouTube. 9 October 2021. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ "Deutscher Genesis Fanclub it / Peter Gabriel / Peter Gabriel: "Playing for Time" ab Mitternacht". 6 March 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Scoop (18 October 2023). "Peter Gabriel Details I/O, His First New Album in 21 Years". consequence.com. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (30 November 2023). "Older and Wiser, Peter Gabriel Is Still Looking Ahead". The New York Times. Retrieved 30 November 2023.

- ^ Peter Gabriel - Full Moon Update November 2023, 27 November 2023, retrieved 1 December 2023

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas. "So – Peter Gabriel (review)". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (28 February 1999). "MUSIC; They're Recording, but Are They Artists?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2013.

- ^ Koskoff, Ellen, ed. (2005). Music Cultures in the United States: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 371. ISBN 978-0-415-96589-7.

- ^ Merlini, Mattia (October 2022). "A Mellotron-Shaped Grave: Deconstructing the Death of Progressive Rock". Transposition (10). doi:10.4000/transposition.7101. hdl:2434/948377. S2CID 250229571. Retrieved 9 August 2023.

Indeed, such an analysis can explain why new post-progressive artists (e.g. Kate Bush, Peter Gabriel, Robert Fripp)

- ^ Easlea 2018, 18: The Tremble in the Hips: So.

- ^ Reed, Ryan (5 July 2016). "20 Insanely Great Peter Gabriel Songs Only Hardcore Fans Know". Rolling Stone. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ Akkerman, Gregg (2016). "Series Editor's Foreword". Experiencing Peter Gabriel: A Listener's Companion. By Bowman, Durrell. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. x. ISBN 9781442252004.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (n.d.). "Peter Gabriel Biography, Songs, & Albums". AllMusic. Retrieved 19 March 2022.

- ^ "Another Day". katebushencyclopedia. 14 August 2017. Archived from the original on 28 November 2018. Retrieved 27 November 2018.

- ^ "Mister Heartbreak – Laurie Anderson | Songs, Reviews, Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "The Woman's Boat – Toni Childs | Credits | AllMusic". AllMusic. Archived from the original on 12 March 2018. Retrieved 12 March 2018.

- ^ "Volume 3: Further in Time". Realworldrecords.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ Hot chip peter gabriel cape cod kwassa kwassa vampire weekend cover, retrieved 26 February 2021

- ^ New collaboration with Arcade Fire, petergabriel.com, retrieved 17 May 2022

- ^ Kornhaber, Spencer (26 November 2019). "Coldplay Would Like to Save the World With Vagueness". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on 28 November 2019. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- ^ Capital Radio interview with Alan Freeman, broadcast October 1982; transcribed in Gabriel fanzine White Shadow (#3, pp13) by editor Fred Tomsett

- ^ "See it. Film it. Change it. Using video to open the eyes of the world to human rights violations". Witness.org. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Geoffrey Oryema – Real World Records". Realworldrecord.com. Archived from the original on 31 July 2018. Retrieved 9 August 2018.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel goes ape for research project". Top40-Charts.com. Archived from the original on 24 December 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "2006 | Nokia Museum". nokiamuseum.info. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "MUDDA – Eno and Gabriel Behind Music Manifesto". Synthtopia.com. 5 February 2004. Archived from the original on 28 August 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Crabbyappleton (27 January 2004). "Peter Gabriel and Brian Eno unveil 'MUDDA' digital manifesto". Myce.com. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Axelle Red age, hometown, biography". Last.fm. Retrieved 26 February 2021.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel Gets Myst-ified". IGN.com. 23 September 2004. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel Gets Myst-ified". IGN.com. 23 September 2004. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel and David Engelke purchase Solid State Logic". 21 June 2005. Archived from the original on 4 April 2012. Retrieved 19 September 2011.

- ^ Weiss, David (5 March 2018). "Who Bought SSL? Inside the Acquisition That Surprised the Console World". SonicScoop. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ^ Breen, Christopher (27 May 2008). "B&W and Real World Launch Music Club". PC World. Archived from the original on 24 June 2011. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Asteroid Day Takes Aim at Our Cosmic Blind Spot: Threats From Above". NBC News. 29 June 2015. Archived from the original on 30 June 2015. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel talks about his work for Amnesty International". YouTube. 28 May 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel TV Interview on NBC Today Show about Amnesty concerts". YouTube. 22 April 2008. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "The North South Prize of Lisbon". North-South Centre. Council of Europe. Archived from the original on 15 February 2008. Retrieved 21 January 2008.

- ^ "Ms. Vera Duarte, Minister of Education, Cape Verde" (PDF). Council of Europe. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Mossman, Kate (3 October 2013). "Peter Gabriel: Pop stardom and reimagining politics". Newstatesman.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2016. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ "Die Quadriga – Award 2008". Loomarea.com (in German). Archived from the original on 15 September 2008. Retrieved 16 July 2011.

- ^ "Iran stoning case woman ordered to name campaigners". The Guardian. London. 22 July 2010. Archived from the original on 31 January 2017. Retrieved 12 December 2016.

- ^ "Peter Gabriel speaks of the loss of Nelson Mandela". Peter Gabriel. 6 December 2013. Archived from the original on 10 December 2013. Retrieved 6 December 2013.

- ^ "Video: Peter Gabriel speaks of the loss of Nelson Mandela". Belfast Telegraph. Archived from the original on 13 December 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Meikle, James (20 May 2014). "Jane Goodall and Peter Gabriel urge Air France to stop ferrying lab monkeys". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 28 January 2015.

- ^ "Banksy marks third anniversary of Syria conflict". BBC News. 13 March 2014. Archived from the original on 5 May 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ Kreps, Daniel (29 November 2014). "Peter Gabriel, Pussy Riot Show Support for Hong Kong Protestors". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on 1 December 2014. Retrieved 30 November 2014.