Pelvic floor dysfunction

| Pelvic floor dysfunction | |

|---|---|

| Specialty | Obstetrics and gynaecology Physical therapy |

Pelvic floor dysfunction is a term used for a variety of disorders that occur when pelvic floor muscles and ligaments are impaired. The condition affects up to 50 percent of women who have given birth.[2] Although this condition predominantly affects women, up to 16 percent of men are affected as well.[3] Symptoms can include pelvic pain, pressure, pain during sex, urinary incontinence (UI), overactive bladder, bowel incontinence, incomplete emptying of feces, constipation, myofascial pelvic pain and pelvic organ prolapse.[4][5] When pelvic organ prolapse occurs, there may be visible organ protrusion or a lump felt in the vagina or anus.[5][6] Research carried out in the UK has shown that symptoms can restrict everyday life for women. However, many people found it difficult to talk about it and to seek care, as they experienced embarrassment and stigma. [7][8]

Common treatments for pelvic floor dysfunction are surgery, medication, physical therapy and lifestyle modifications.[2]

The term "pelvic floor dysfunction" has been criticized since it does not represent a particular pelvic floor disorder.[9] It has therefore been recommended that the term not be used in medical literature without additional clarification.[9]

Epidemiology

[edit]Pelvic floor dysfunction is defined as a herniation of the pelvic organs through the pelvic organ walls and pelvic floor. The condition is widespread, affecting up to 50 percent of women at some point in their lifetime.[10] About 11 percent of women will undergo surgery for urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse by age 80.[11] Women who experience pelvic floor dysfunction are more likely to report issues with arousal combined with dyspareunia. For women, there is a 20.5% risk for having a surgical intervention related to stress urinary incontinence. The literature suggests that white women are at increased risk for stress urinary incontinence.[12]

Though pelvic floor dysfunction is thought to more commonly affect women, 16% of men have been identified with pelvic floor dysfunction.[13] Pelvic floor dysfunction and its multiple consequences, including urinary incontinence, is a concerning health issue becoming more evident as the population of advancing age individuals rises.

Causes

[edit]Mechanistically, the causes of pelvic floor dysfunction are two-fold: widening of the pelvic floor hiatus and descent of pelvic floor below the pubococcygeal line, with specific organ prolapse, graded relative to the hiatus.[10] People with an inherited deficiency in their collagen type may be more likely to develop pelvic floor dysfunction. Additionally, people with congenitally weak connective tissue and fascia are at an increased risk for stress urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.[10] Recent literature demonstrates that defects in endopelvic fascia and compromised levator ani muscle function have been categorized as important etiologic factors in the development of pelvic floor dysfunction. Some circumstances are clearly associated with collagen defects. These include vaginally delivering a child, being post-menopausal, and being of advanced age.[13]

Some lifestyle behaviors can lead to pelvic floor dysfunction. This includes avoiding urinating or bowel movements, obesity, use of muscle relaxants or narcotics, and use of antihistamines or anticholinergics. Using muscle relaxants or narcotics can lead to increased smooth and skeletal muscle relaxation, potentially related to urinary incontinence. Antihistamines and anticholinergics may have additive effects that lead to urinary hesitancy and retention, ultimately leading to pelvic floor dysfunction. Urinary incontinence can also affect athletes, especially those in sports that require high impact such as jumping.[13] Gymnasts, for example, report a high prevalence of urinary incontinence. Studies show that athletes in sports requiring high spinal stability may also have this condition, as the activation of abdominal wall muscles can cause urinary alterations during activities.[14] In some cases, sexual abuse can also be associated with chronic pelvic pain and pelvic floor dysfunction.[13]

Pelvic floor dysfunction can result after pelvic radiation, as well as other treatments for gynecological cancers.[15]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Pelvic floor dysfunction can be assessed with a strong clinical history and physical exam, though imaging is often needed for diagnosis. As part of the clinical history, a healthcare provider may ask about obstetric history, including how many pregnancies and deliveries, what mode of delivery and if there were any complications during delivery.[5] Providers will also ask about presence and severity of symptoms such as pelvic pain or pressure, problems with urination or defecation, painful sex, or sexual dysfunction. The physical exam may include both examination with a speculum to visualize the cervix and check for inflammation, as well as manual examination with the provider's fingers to assess for pain and strength of pelvic floor muscle contraction.[13]

Imaging provides a more complete picture of the type and severity of pelvic floor dysfunction than history and physical exam alone. Historically, fluoroscopy with defecography and cystography were used. More recently, MRI has been used to complement and sometimes replace fluoroscopic assessment of the disorder. This technique is less invasive, and allows for less radiation exposure and increased patient comfort, though an enema is required the evening before the procedure. Both fluoroscopy and MRI assess the pelvic floor at rest and during maximum strain using coronal and sagittal views.[17]

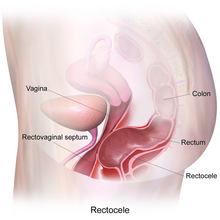

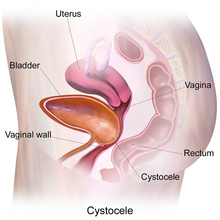

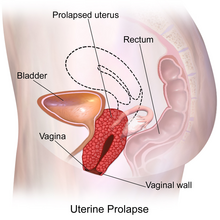

When grading individual organ prolapse for severity, the rectum, bladder and uterus are individually assessed. Prolapse of the rectum is referred to as a rectocele, bladder prolapse through the anterior vaginal wall is called a cystocele, and prolapse of the small bowel is an enterocele.[17] To assess the degree of dysfunction, three measurements are taken into account. First, an anatomic landmark known as the pubococcygeal line must be determined, which is a straight line connecting the inferior margin of the pubic symphysis at the midline with the junction of the first and second coccygeal elements on a sagittal image. After this, the location of the puborectalis muscle sling is assessed, and a perpendicular line between the pubococcygeal line and muscle sling is drawn. This line provides a reference point for the measurement of pelvic floor descent. Descent greater than 2 cm below this line is considered mild and descent greater than 6 cm is considered severe. Lastly, a line from the pubic symphysis to the puborectalis muscle sling is drawn, which is a measurement of the pelvic floor hiatus. Measurements greater than 6 cm are considered mild, and greater than 10 cm severe. The degree of organ prolapse is assessed relative to the hiatus.

The grading for organ prolapse relative to the hiatus is more strict. Any descent below the hiatus is considered abnormal, and descent greater than 4 cm is considered severe.[6]

Ultrasound can also be used to diagnose pelvic floor dysfunction. Transabdominal, transvaginal, transperineal and endoanal ultrasound (EUS) are important tools for diagnosing pelvic floor dysfunction. For EUS, an ultrasound probe is inserted into the anal canal and can be used to visualize and assess the anatomy and function the pelvic floor.[18] Ultrasound is easily accessible and noninvasive; however, it may compress certain structures, does not produce high-quality images and cannot be used to visualize the entire pelvic floor.[19]

Treatment

[edit]There are several approaches to treatment of pelvic floor dysfunction, and often several approaches are used in combination.

Physical therapy

[edit]Pelvic floor muscle (PFM) training is vital for treating different types of pelvic floor dysfunction. Two common problems are uterine prolapse and urinary incontinence both of which stem from muscle weakness. Pelvic floor muscle therapy is the first line of treatment for urinary incontinence and thus should be considered before more invasive procedures such as surgery.[20] Being able to control the pelvic floor muscles is vital for a well functioning pelvic floor. Without the ability to control the pelvic floor muscles, pelvic floor training cannot be done successfully. Pelvic floor muscle therapy strengthens the muscles of the pelvic floor through repeated contractions of varying strength.[20] Through vaginal palpation exams and the use of biofeedback, the tightening, lifting, and squeezing actions of these muscles can be determined. Biofeedback can be used to treat urinary incontinence as it records contractions of the pelvic floor muscles and can help patients become aware of the use of their muscles.[14] PFM training can also increase female sexual satisfaction by improving sexual function and the ability to orgasm.[21] In men, PFM exercises can also help maintain a strong erection.[22]

In addition, abdominal muscle training has been shown to improve pelvic floor muscle function.[23] By increasing abdominal muscle strength and control, a person may have an easier time activating the pelvic floor muscles in sync with the abdominal muscles. Many physiotherapists are specially trained to address the muscle weaknesses associated with pelvic floor dysfunction and can effectively treat pelvic floor dysfunction through strengthening exercises.[24] Overall, physical therapy can significantly improve the quality of life of those with pelvic floor dysfunction by relieving symptoms.

Medication

[edit]Overactive bladder can be treated with medications, including those in the class of antimuscarinics and beta 3 agonists. Antimuscarinics are the most commonly used, however, beta 3 agonists can be used for those that are unable to take antimuscarinics due to side effects or other reasons.[4]

Devices

[edit]A pessary is a plastic or silicone device that may be used for women with pelvic organ prolapse. Vaginal pessaries can immediately relieve prolapse and prolapse-related symptoms.[25] This treatment is useful for individuals who do not want to have surgery or are unable to have surgery due to the risk of the procedure. Some pessaries have a knob that can also treat urinary incontinence. To be effective, pessaries must be fitted by a medical provider and the largest device that fits comfortably should be used.[26]

Other devices train the pelvic floor via internal exercises with biofeedback mechanisms.[27]

Lifestyle modifications

[edit]Treatment for pelvic floor dysfunction, especially the symptom of urinary incontinence, is essential, but so is prevention. Patients are usually encouraged to change their lifestyles; interventions such as reducing body weight, limiting the use of stimulants, quitting smoking, limiting strenuous efforts, preventing constipation and increasing physical activity can help prevent pelvic floor dysfunction.[14] For those that already have diagnosed pelvic floor dysfunction, symptoms can be eased by physical activity, especially abdominal exercises and pelvic floor exercises (Kegels) that strengthen the pelvic floor. Symptoms of urinary incontinence can also be reduced by making dietary changes such as limiting intake of acidic and spicy foods, alcohol and caffeine.[13]

Surgery

[edit]Surgery is performed when desired by the patient or when less invasive treatments, such as lifestyle modification and physical therapy, are not effective.[28] There are various procedures used to address prolapse. Cystoceles are treated with a surgical procedure known as a Burch colposuspension, with the goal of suspending the prolapsed urethra so that the urethrovesical junction and proximal urethra are replaced in the pelvic cavity. Uterine prolapse is treated with hysterectomy and uterosacral suspension. With enteroceles, the prolapsed small bowel is elevated into the pelvis cavity and the rectovaginal fascia is reapproximated. Rectoceles, in which the anterior wall of the rectum protrudes into the posterior wall of the vagina, require posterior colporrhaphy, also known as repair of the vaginal wall.[29] Though pelvic floor dysfunction is more common in women, there are also proven methods to assist men. In severe cases of pelvic floor dysfunction causing urinary incontinence, a radical prostatectomy followed by postoperative pelvic floor muscle therapy is an option.[30]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "11.4 Axial Muscles of the Abdominal Wall, and Thorax - Anatomy and Physiology | OpenStax". openstax.org. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ^ a b Hagen S, Stark D (December 2011). "Conservative prevention and management of pelvic organ prolapse in women". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 12 (12): CD003882. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003882.pub4. PMID 22161382.

- ^ Smith CP (2016). "Male chronic pelvic pain: An update". Indian Journal of Urology. 32 (1): 34–9. doi:10.4103/0970-1591.173105. PMC 4756547. PMID 26941492.

- ^ a b Hong MK, Ding DC (2019-10-01). "Current Treatments for Female Pelvic Floor Dysfunctions". Gynecology and Minimally Invasive Therapy. 8 (4): 143–148. doi:10.4103/GMIT.GMIT_7_19. PMC 6849106. PMID 31741838.

- ^ a b c McNevin MS (February 2010). "Overview of pelvic floor disorders". The Surgical Clinics of North America. 90 (1): 195–205, Table of Contents. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2009.10.003. PMID 20109643.

- ^ a b Boyadzhyan L, Raman SS, Raz S (2008). "Role of static and dynamic MR imaging in surgical pelvic floor dysfunction". Radiographics. 28 (4): 949–67. doi:10.1148/rg.284075139. PMID 18635623.

- ^ Toye, F (2023). "Exploring the experiences of people with urogynaecology conditions in the UK: a reflexive thematic analysis and conceptual model". BMC Women's Health. 23 (1): 431. doi:10.1186/s12905-023-02592-w. PMC 10426194. PMID 37580761.

- ^ "Pelvic floor and bladder problems can make people feel embarrassed, and have an impact on everyday life". NIHR Evidence. 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_61000.

- ^ a b Bordeianou, LG; Carmichael, JC; Paquette, IM; Wexner, S; Hull, TL; Bernstein, M; Keller, DS; Zutshi, M; Varma, MG; Gurland, BH; Steele, SR (April 2018). "Consensus Statement of Definitions for Anorectal Physiology Testing and Pelvic Floor Terminology (Revised)". Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 61 (4): 421–427. doi:10.1097/DCR.0000000000001070. PMID 29521821.

- ^ a b c Boyadzhyan L, Raman SS, Raz S (July 2008). "Role of static and dynamic MR imaging in surgical pelvic floor dysfunction". Radiographics. 28 (4): 949–67. doi:10.1148/rg.284075139. PMID 18635623.

- ^ Fialkow MF, Newton KM, Lentz GM, Weiss NS (March 2008). "Lifetime risk of surgical management for pelvic organ prolapse or urinary incontinence". International Urogynecology Journal and Pelvic Floor Dysfunction. 19 (3): 437–40. doi:10.1007/s00192-007-0459-9. PMID 17896064. S2CID 10995869.

- ^ Kim S, Harvey MA, Johnston S (March 2005). "A review of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of pelvic floor dysfunction: do racial differences matter?". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 27 (3): 251–9. doi:10.1016/S1701-2163(16)30518-7. PMID 15937599.

- ^ a b c d e f Grimes WR, Stratton M (2021). "Pelvic Floor Dysfunction". StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 32644672. Retrieved 2021-09-17.

- ^ a b c Kopańska M, Torices S, Czech J, Koziara W, Toborek M, Dobrek Ł (2020-06-25). "Urinary incontinence in women: biofeedback as an innovative treatment method". Therapeutic Advances in Urology. 12: 1756287220934359. doi:10.1177/1756287220934359. PMC 7325537. PMID 32647538.

- ^ Ramaseshan AS, Felton J, Roque D, Rao G, Shipper AG, Sanses TV (April 2018). "Pelvic floor disorders in women with gynecologic malignancies: a systematic review". International Urogynecology Journal. 29 (4): 459–476. doi:10.1007/s00192-017-3467-4. PMC 7329191. PMID 28929201.

- ^ a b "Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International — CC BY-SA 4.0". creativecommons.org. Retrieved 2021-09-13.

- ^ a b El Sayed RF, El Mashed S, Farag A, Morsy MM, Abdel Azim MS (August 2008). "Pelvic floor dysfunction: assessment with combined analysis of static and dynamic MR imaging findings". Radiology. 248 (2): 518–30. doi:10.1148/radiol.2482070974. PMID 18574134. S2CID 5491294.

- ^ Silviera, Matthew; Keller, Deborah S. (2019), "Pelvic Floor Dysfunction", Shackelford's Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 2 Volume Set, Elsevier, pp. 1750–1760, doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-40232-3.00150-3, ISBN 978-0-323-40232-3, S2CID 81434962, retrieved 2021-09-20

- ^ Woodfield, Courtney A.; Krishnamoorthy, Saravanan; Hampton, Brittany S.; Brody, Jeffrey M. (June 2010). "Imaging Pelvic Floor Disorders: Trend Toward Comprehensive MRI". American Journal of Roentgenology. 194 (6): 1640–1649. doi:10.2214/AJR.09.3670. ISSN 0361-803X. PMID 20489108. S2CID 32893848.

- ^ a b Arnouk A, De E, Rehfuss A, Cappadocia C, Dickson S, Lian F (June 2017). "Physical, Complementary, and Alternative Medicine in the Treatment of Pelvic Floor Disorders". Current Urology Reports. 18 (6): 47. doi:10.1007/s11934-017-0694-7. PMID 28585105. S2CID 5230186.

- ^ Verbeek M, Hayward L (October 2019). "Pelvic Floor Dysfunction And Its Effect On Quality Of Sexual Life". Sexual Medicine Reviews. 7 (4): 559–564. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2019.05.007. PMID 31351916. S2CID 198965002.

- ^ "The big squeeze: welcome to the pelvic floor revolution". the Guardian. 2021-04-29. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ Mateus-Vasconcelos EC, Ribeiro AM, Antônio FI, Brito LG, Ferreira CH (June 2018). "Physiotherapy methods to facilitate pelvic floor muscle contraction: A systematic review". Physiotherapy Theory and Practice. 34 (6): 420–432. doi:10.1080/09593985.2017.1419520. PMID 29278967. S2CID 3885851.

- ^ Vesentini G, El Dib R, Righesso LA, Piculo F, Marini G, Ferraz GA, et al. (2019). "Pelvic floor and abdominal muscle cocontraction in women with and without pelvic floor dysfunction: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Clinics. 74: e1319. doi:10.6061/clinics/2019/e1319. PMC 6862713. PMID 31778432.

- ^ Boyd, S.S.; Propst, K.; O'Sullivan, D.M.; Tulikangas, P. (March 2019). "25: Pessary use and severity of pelvic organ prolapse over time: a retrospective study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 220 (3): S723. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.055. ISSN 0002-9378.

- ^ Jones KA, Harmanli O (2010). "Pessary use in pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence". Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 3 (1): 3–9. PMC 2876320. PMID 20508777.

- ^ "Bluetooth your bladder: the hi-tech way to beat incontinence". the Guardian. 2019-06-02. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

- ^ Conway CK, White SE, Russell R, Sentilles C, Clark-Patterson GL, Miller KS, et al. (2020-12-21). "Pelvic Organ Prolapse: A Review of In Vitro Testing of Pelvic Support Mechanisms". The Ochsner Journal. 20 (4): 410–418. doi:10.31486/toj.19.0089. PMC 7755550. PMID 33408579.

- ^ "Pelvic Floor Dysfunction Expanded Version | ASCRS". www.fascrs.org. Retrieved 2017-12-02.

- ^ Strączyńska A, Weber-Rajek M, Strojek K, Piekorz Z, Styczyńska H, Goch A, Radzimińska A (2019-11-12). "The Impact Of Pelvic Floor Muscle Training On Urinary Incontinence In Men After Radical Prostatectomy (RP) - A Systematic Review". Clinical Interventions in Aging. 14: 1997–2005. doi:10.2147/cia.s228222. PMC 6858802. PMID 31814714.