Pavement light

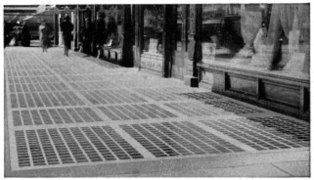

Pavement lights (UK), vault lights (US), floor lights, or sidewalk prisms are flat-topped walk-on skylights, usually set into pavement (sidewalks) or floors to let sunlight into the space below. They often use anidolic lighting prisms to throw the light sideways under the building. They were developed in the 19th century, but declined in popularity with the advent of cheap electric lighting in the early 20th. Older cities and smaller centers around the world have, or once had, pavement lights.[1] In the early 21st century, such lights are over a century old,[2] although lights are being installed in some new construction.[3]

Uses

[edit]Sidewalk prisms are a method of daylighting basements, and are able to serve as a sole source of illumination during the day. At night, lighting in the basements beneath produces a glowing sidewalk.[4] Vault lights may be used to make subterranean space useful.[2] They are more common in city centers, dense, high-rent areas where space is valuable.[2]

Historically, landlords took an interest in improving not only the floor area ratio, but the amount of space that was naturally lit, on the grounds that this was profitable.[5] Occupiers valued daylight not only as a way of saving on artificial lighting costs, which were higher historically, but also as a way to let premises remain cooler in summer, and a way to save on ventilation costs, if using gas lighting rather than arc lamps or early incandescent lights.[5]

Pavement lights and related products were historically marketed as a way of saving on artificial lighting costs and making space more usable and pleasant.[5] Modern studies of similar daylighting technology provide evidence for those claims.[6]

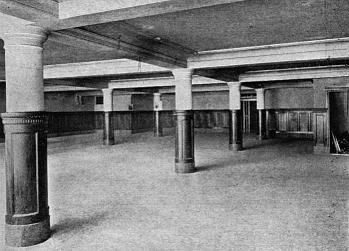

Vault lights also are used in floors under glass roofs, for example in Budapest's historic Párizsi udvar[7] and New York's mostly-demolished old Pennsylvania Station ().[8] Vault lights also could be set into the basement floor, underneath other vault lights, creating a double-deck arrangement, which would light the subbasement.[9] Manhole covers and coalhole covers with lighting elements were also made.[2] Some steps have vault lights set into the vertical stair risers.[10]

History

[edit]A basement that extends below a sidewalk or pavement is called an areaway,[2] a vaulted sidewalk,[11] or a hollow sidewalk.[12] In some cities, these areaways were created by the raising of the street level to combat floods, and in some cases they form, an often now abandoned, tunnel network.[13][12][14] To light these spaces, sidewalks incorporated gratings, which were a trip hazard and let water and street dirt as well as light into the basement. Replacing the open gratings with glass was an obvious improvement.[15]

Frames

[edit]

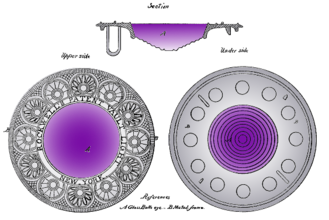

Sidewalk prisms developed from deck prisms, which were used to let light through the decks of ships. The earliest pavement light (Rockwell, 1834)[16] used a single large round glass lens set in an iron frame. The large lens was directly exposed to traffic, and if the lens broke, a large hole was left in the pavement, which was potentially unsafe for pedestrians.[15][17]

Thaddeus Hyatt corrected these faults with his "Hyatt light" of 1854.[17] Many small lenses ("bull's-eyes") were set in a wrought-iron frame,[18][15] (later cast iron),[19] and the frame included raised nubs around each lens to improve traction in wet weather and to protect them from damage and wear. Even if all the lenses were broken out, the panel would still be safe to walk on.[15]

In the 1930s, London authorities ruled that glass sections could not be larger than 100 mm by 100 mm.[20] Modern glass floors are made of laminated and toughened glass pavers, which can be substantially larger. They have an upper protective layer that can be replaced if it becomes chipped or cracked.[21] The top surface of the pavers may also be chosen and treated to improve traction.[22]

Wrought iron,[18][15] cast iron,[19] and stainless steel[23] frames have all been used. Reinforced concrete slabs began to replace iron frames in the 1890s in New York. Benefits claimed included less condensation (due to the lower thermal conductivity)[24] and a less slippery surface when wet.[3] Concrete panels may be pre-cast or cast in-situ.[25][26]

Late concrete panels often were made with metal-framed "armored prisms", which were intended to prevent breakage and make replacing individual prisms easier. The glass is not cast into the concrete but caulked into the frame. Rather than chiselling out the old glass, the glass can be popped out of the frame.[27]

Translucent concrete has also been proposed as a floor material.[28] This would essentially make it a vault light with very small (fiberoptic) lighting elements. It also innately redirects the light from the angle of incidence to an angle ~parallel to the optical fibers (usually, perpendicular to the surface of the concrete).

Transparent elements

[edit]The transparent elements may be referred to as prisms or lenses, depending on shape, or as jewels.[15]

Glass color

[edit]

The glass in many old pavement lights is now either purple or straw-colored. This is a side-effect of the manufacturing process. Pure silica glass is transparent, but older glass manufacture often used silica from sand, which contains iron and other impurities.[29] Iron produces a greenish tint in the finished glass. To remove this effect, a "decolorizer" such as manganese dioxide ("glassmakers' soap") was added during the manufacture of the glass.

When exposed to ultraviolet light, the manganese slowly "solarizes", turning purple,[29] which is why many existing sidewalk prisms are now purple.[4] WWI increased demand for manganese in the US and cut off the supply of high-grade ore from Germany,[30] so selenium dioxide was used as a decolorizer instead.[31] Selenium also solarizes, but to a straw color.[29]

Replacement glass that has been tinted purple deliberately, in order to match the current colour, has been used in some historic restoration projects.[32]

Glass shape

[edit]In 1871 London, Hayward Brothers patented their "semi-prism": changing the shape of the glass by adding pendant prisms to the underside reflects the light sideways, allowing it to light the area under the main building. The pendant shapes were right-angle ("half") prisms, which reflected all incoming light sideways.[15] The horizontal ridges protruding from the top of the prism let it be set into an opening in an iron or cement grating.

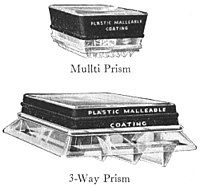

Some cast glass pendant prisms have flat portions to shed light directly below, as well as throwing it sideways under the main body of the building (see image). Some prisms were made with multiple pendant prisms, either as a Fresnel-lens-like sheet of identical prisms ("multi") or a sheet of dissimilar prisms that could distribute the light ("three-way" etc.).[33]

The precise angles at which the prisms refracted or reflected light was important. An installation would generally consist of multiple different prescriptions of prism, chosen either by an on-site expert contractor or by a layman using standard algorithms.[5] This also would diffuse the light somewhat, as would the rough glass surfaces (the lenses are translucent, not transparent).

Larger castings are more expensive, not only because they use more glass, but because they take longer to cool.[34] Modern glass floors use laminate sheet glass some centimeters (more than an inch) thick. It often is transparent.[21]

Non-glass translucent materials

[edit]Synthetic resin composites (such as fiberglass), as well as plastics such as Lexan, have been proposed to replace missing prism lights.[35] Translucent decking panels made of fiberglass are often used for balconies which would otherwise shade the windows below them.[36] Peel-and-stick prism films recently have come on the market, with acrylic micro-prisms that internally reflect light somewhat like glass pendant prisms.[6][37][38]

Structure

[edit]-

Two-stage refraction system for basement lighting; prism wall below center, shop above left. Note I-beam and masonry wall.

-

The same system used to light a salesroom inside a hollow sidewalk; prism wall is on the right

-

A basement daylit by sidewalk prisms (prisms out-of-shot to the left)

In some cases, a second vertical curtain of prisms was installed under the building sill.[18] These were analogous to the prism transoms used over above-ground windows and doors. The light could be bent in two stages and used to daylight the whole basement.[18]

The areaway under a sidewalk light usually has a masonry wall separating it from the soil under the street, although it may extend partly under the street. Support for the vault light frames varies. Steel cross-beams supported by columns are common in older buildings; metal decks are common in newer ones.[11]

Current state and trends

[edit]Manufacture, maintenance, and repair

[edit]Some modern pavement lights are quite different from historic ones,[21][15] so restoration and replacement may use different techniques and parts.

A few companies now manufacture and sell vault lights, either as glass-only, prefab panels, or installation.[2][39] Construction methods and prices vary widely.[39] Historically, glass lenses were standardized by each manufacturer; some modern manufacturers produce standardized prisms.[5][2][19] Some firms also supply replacement glass castings to order.[39] Cost varies greatly; shapes needing complicated articulated moulds are more expensive.[2]

Modern caulking materials are used for caulking in replacement glass. Broken and damaged frames can be patched, re-welded,[9] or re-cast.[9][19] Generally speaking, restoration requires only simple tools and technology.[9]

Promptly repairing sidewalk cracks, and avoiding de-icers that will corrode metal, helps keep the supporting structure dry and in good repair.[11] Keeping a sidewalk light watertight does not cost much in time or materials.[9] Vaults generally last many decades,[11] and many extant vaults are more than a century old.[2]

Reuse and preservation

[edit]Despite their reusability and repairability, old panels often are landfilled.[40][4][2] However, the city of Victoria, Canada is stockpiling removed pavement light panels for future restoration projects.[4][2] Often, individual broken sidewalk prisms are not replaced, but instead, the opening is filled with concrete or other opaque materials,[2] such as metal, wood, and asphalt.[9]

When a building is renovated, vault lights may be removed or concreted over. For instance, the floor of New York's mostly-demolished old Pennsylvania Station was made of vault lights, to let light through the concourse floor onto the platforms.[8] The undersides of the lights can still be seen, but the tops have been concreted over (see images).[41]

While some cities have preservation measures for vault lights, others actively remove them and fill areaways.[2] Sometimes the outside appearance of the lights is retained while filling the areaway and setting the lights in a concrete pad, removing their daylighting function.[9] Some areaways are "mothballed"; that is, filled with gravel that could later be removed.[2]

Areaways are used in some cities as a convenient place to run utilities, which may make the cities reluctant to give areaways legal protection.[2] In some cases, utility construction leads to areaways being filled.[13]

Load-bearing strength

[edit]The load-bearing strength of vault lights varies widely with span, construction, and state of repair. Some damaged vaults may not be able to support a fire engine,[42] which a sidewalk vault in sound condition should be able to do.[11] Many jurisdictions do not have regulations on the load-bearing capacity of pavement lights, and manufacturers may develop their own loading standards, in compliance with local fire department regulations. The load-bearing capacity of pavement lights can be tested, and lights can be designed and built to specific load-bearing capacities.[43]

Damp areaways may corrode the steel load-bearing elements supporting the pavement roof. Moisture may come from leakage from above or from groundwater from below.[2]

Current installations

[edit]

- Amsterdam, The Netherlands, has vault lights, some of which have been documented by the Netherlands Department for Conservation.[44]

- Astoria, Oregon, has a community program for restoring vault lights, funded by the Astoria Downtown Historic District Association. A volunteer plan to replace broken glass with squares of Lexan, topped with resin embedded with glass teardrops, was prevented by legislation.[35]

- Budapest, Hungary, has vault lights in one of its tourist sites, the Art Deco-period Párizsi udvar mall on Ferenciek tere (Square of the Franciscans). The mall has unusual, decorative pavement lights let into its polychrome tile floor, to allow light from the glass dome skylights into the basement level. There also are vault lights in other locations, such as in the old post office building.[7]

- Chicago, Illinois, has extremely extensive sidewalk vaults, but many of them do not have vault lights. There is no inventory of them. The city is filling in all vaults, as some are structurally unsound.[14] See also the raising of Chicago.

- Deadwood, South Dakota, funded a major restoration and maintenance project for vault lights in approximately 2000.[2]

- Dublin, Ireland has many vault lights.[45]

- Dunedin, New Zealand has well-preserved Luxfer and Hayward Brothers vault lights.[46]

- London, England has many vault lights, many made by the Hayward Brothers.[47] Historic preservation legislation encourages a market in new pavement lights.

- New York City has large numbers of vault lights, mostly in the SoHo district. More than half of the subway stations originally had vault lights, but these had mostly been blocked off. Installing and restoring vault lights has become part of modern construction practices.[3] The city government has no policies or records about vault lights.[2]

- Philadelphia, Pennsylvania has numerous vault lights, some of them locally manufactured.[48]

- Portland, Oregon has prisms at several locations.[49] It has no preservation project for its prisms, however, and fills those that break with concrete.[2] There is some local opposition to the policy.[50] See also Portland Underground.

- Pretoria, South Africa has Hayward vault lights.[51]

- Sacramento, California has "hollow sidewalks", which originated when the city raised its street level to combat floods; some of these spaces are lit by vault lights. There are many stories told about these areas.[12]

- Salem, Oregon has an extensive tunnel network with vault lights.[52] Historians have found a mural-painted grocery drop,[53] a disco, a swimming pool, a firing range, opium dens, and bordellos in the tunnels.[13] Guided tours are sometimes conducted in the tunnels.[54][52] The Go Downtown Salem! Board welcomed the idea of regular underground tours.[53] Many of the tunnels have been filled during sewer construction.[13]

- San Diego, California has sixteen-sided pavement jewels of the "Searchlight" brand.[55]

- San Francisco evaluates the lights as having little historic value, and as a safety hazard for pedestrians.[56] Most of the lights have been removed.[2] The City Lights Bookstore has vault lights.[57]

- Saskatoon, Saskatchewan has had sidewalk prisms. They have been used in music videos, and a Facebook group fought to save them.[58] They were scheduled to be infilled in 2015.[59]

- Seattle, Washington raised its street level, by up to 22 feet in some places, in the aftermath of the Great Seattle Fire of 1889.[2] Previously, the Pioneer Square area had flooded tidally.[2] Seattle replaced some of its sidewalk vault lights in Pioneer Square with new pre-purpled ones in 2002. Seattle runs tourist trips through its underground.[32]

- Tijuana, Mexico has armoured unsolarized vault lights in the 1919 Casa de la Cultura.[60]

- Toronto, Ontario once had many vault lights, but the last known remaining example were in front of the shops at 2869 Dundas Street West (near Keele) until 2011.[61]

- Vancouver, British Columbia has an unofficial policy of requiring any applicants for development permits to fill in areaways,[42][2] although some have been paved over or made sufficiently load-bearing to support a fire engine.[57] Some of the remaining areaways have restaurants built into them.[62] A walking map of the sidewalk prisms has been produced.[63][57] There are ~130 remaining areaways, the records of which are not digitised, and no measures exist to promote their preservation.[2]

- Victoria, British Columbia has more than eleven thousand sidewalk prisms in seven locations (as of 2006), including an underground gallery running around an entire block outside the Yarrow Building. More than 670 of the prisms are missing or filled with concrete.[2] Sidewalk prisms have been heritage-registered since 1990. Originally, there were hundreds of thousands of prisms. The city has some panels in storage for restoration, but is having difficulty finding a glass supplier. There are city plans to light the galleries below at night, creating glowing purple sidewalks in the downtown core.[4] While they are protected, there is no funding for the preservation of sidewalk prisms.[2]

Gallery

[edit]-

The Párizsi udvar in Budapest, with pavement lights let into its polychrome tile floor to allow light from the glass dome skylights into the basement level (details)

-

The Brookfield Place in Toronto, Canada, at night

-

A similar floor by day at the Liège-Guillemins railway station in Belgium

-

The floor of the rotunda of the Michigan State Capitol has a wrought-iron frame shaped to give the illusion of a bowl shape from above (from below)

-

In a glass-covered courtyard in the Museo Arqueológico de Linares

-

Translucent fiberglass deck of a bridge in Lleida, Spain, lit from below

-

Translucent fiberglass pavement light built into a balcony, allowing sunlight into the area under the deck

-

An area under a sidewalk, 1915, showing clear glass

-

Purple-solarized vault lights from ca. 1880, Etna, California

-

Purpled and patched vault lights outside the historic Chamberlin Hotel in Portland, Oregon. Grouting has been used to re-seal cracked glass jewels.

-

A pavement light set into the pavement outside a store (close-up)

-

A pavement light outside Burlington House in London, England

-

Armoured vault lights installed in the sidewalk outside a store

-

Cross-section of a pavement light panel, showing alternating lenses and prisms

-

Pavement lights in Geneva, New York (flash version). Large pendant right-angle prisms as in previous image.

-

Translucent fiberglass pavement light panel, close-up

-

On a terrace

See also

[edit]- Anidolic lighting

- Daylighting

- Deck prism

- Prism lighting

- Thaddeus Hyatt – made the money he spent fighting slavery with Hyatt lights, innovative small-paned lights in cast-iron frames[15]

- Underground city (vault lights are used to light some)[64]

References

[edit]- ^ Macky, Ian, "Prism glass, gallery[of installations worldwide]", Glassian, archived from the original on 21 March 2009

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Marie Wong; et al. (2011), Seattle Prism Light Reconnaissance Study (PDF), Institute for Public Service, Seattle University, archived (PDF) from the original on 27 March 2016

- ^ a b c Gray, Christopher (19 May 2002), "Streetscapes/Subway Platforms; Letting the Sun Shine In", New York Times, archived from the original on 30 April 2014

- ^ a b c d e Ringuette, Janis; Ringuette, Norm (2007), Walking Over History: Victoria's Historic Sidewalk Prisms, archived from the original on 9 May 2008

- ^ a b c d e Henry Crew; Olin H. Basquin, eds. (1898), "Pocket Hand-book of Electro-glazed Luxfer Prisms containing useful information and tables relating to their use For Architects, Engineers and Builders.", Glassian, archived from the original on 10 March 2016

- ^ a b Padiyath, Raghunath (2013). Daylight Redirecting Window Films. serdp-estcp.org (Report). EW-201014. Archived from the original on 29 September 2017. Retrieved 9 October 2017.

- ^ a b "Vault Lights in Budapest, Hungary". glassian. Archived from the original on 12 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ a b Macky, Ian, "Vault Lights in Penn Station, NYC", Glassian, archived from the original on 12 May 2016

- ^ a b c d e f g PRESERVATION Tech Notes: Repair and Rehabilitation of Historic Sidewalk Vault Lights, PTN 47 (PDF), National Park Service (U.S.A.), November 2003, ISSN 0741-9023, archived (PDF) from the original on 6 May 2017 NOTE: colour versions of images available on Commons:Repair and Rehabilitation of Historic Sidewalk Vault Lights at 552-554 Broadway, New York City (2002) (URL formerly "Technical Preservation Services, National Park Service". Archived from the original on 25 April 2011. Retrieved 8 October 2017.)

- ^ "Vault Lights in Chicago, Illinois". glassian. 2 April 2003. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Varone, Stephen; Varsalona, Peter (October 2004), "Replacing a Sidewalk Vault", Habitat Magazine, Ask The Engineer, original publisher: Habitat Magazine at habitatmag.com; now rehosted by Rand Engineering and Architecture, DPC

- ^ a b c Garvin, Cosmo (17 July 2003), "The past below", Sacramento Newsreview, archived from the original on 8 February 2014

- ^ a b c d "From opium dens to bordellos, historian unearths Salem's past". Statesmanjournal.com. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b Lord, Steve (29 September 2017), "Vault project shines light on underground Aurora", The Chicago Tribune, archived from the original on 28 October 2017

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Macky, Ian, "Prism glass", Glassian, archived from the original on 29 September 2017

- ^ a b US X8,058, Rockwell, E., "Rockwell, Vault cover", issued 8 March 1834

- ^ a b US 11,695, Hyatt, Thaddeus, "Hyatt, Vault cover", issued 19 September 1854

- ^ a b c d The Luxfer Prism Co., Ltd. of Canada, Catalogue. Archived 14 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d Hargreaves Foundry (19 November 2014), Replacement of Traditional Pavement Lights, archived from the original on 7 October 2017

- ^ Brassington, Kevan (1 June 2013). "Precast concrete pavement lights". NBS. RIBA Enterprises Ltd. Retrieved 7 December 2019.

- ^ a b c Campbell-Dollaghan, Kelsey (29 May 2014). "The Willis Tower's 103rd Floor Glass Skydeck Cracked Last Night". Gizmodo. Gizmodo.com. Archived from the original on 3 June 2014. Retrieved 4 June 2014.

- ^ WalkerGlass.com. "Anti-slip Glass | Walker Textures™". Walkerglass.com. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Glazed Walk-on Floorlight Access Archived 2017-10-09 at the Wayback Machine, Surespan

- ^ 1906 Sweet's Indexed Catalog of Building Construction Archived 14 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, page 267

- ^ Pavement Lights Archived 7 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Luxcrete Limited

- ^ 1915 Sweet's Indexed Catalog of Building Construction Archived 14 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, page 174

- ^ 1927–1928 Sweet's Indexed Catalog of Building Construction Archived 1 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine, page A387

- ^ "Translucent Concrete: An Emerging Material". Illumin. The Engineering Writing Program at the University of Southern California Viterbi School of Engineering. 3 December 2017. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Solarized glass, Corning Museum of Glass, 8 December 2011, archived from the original on 8 October 2017

- ^ Manganese statistics (PDF), Kelly, T.D., and Matos, G.R., comps., Historical statistics for mineral and material commodities in the United States: U.S. Geological Survey Data Series 140, U.S. Geological Survey, 1 April 2014, archived (PDF) from the original on 24 February 2017, retrieved 9 October 2017

- ^ "Purple Insulator Gallery". glassian. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ a b Minutes of city meetings on sidewalk prisms Archived 4 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine in Seattle, USA, and Victoria, Canada

- ^ Vault Lighting and How It Is Secured Archived 14 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Catalog 14-S, American 3-Way Prism Company

- ^ Bullseye Glass Co., Annealing Thick Slabs, archived from the original on 12 November 2017

- ^ a b Stratton, Edward (7 December 2015), "Let the light in", The Daily Astorian, archived from the original on 9 October 2017

- ^ "GLOBALGRID™ Translucent Decking". Frpresource.com. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Object of the Moment: 3M Daylight Redirecting Film by 3M Archived 20 March 2017 at the Wayback Machine, by Selin Ashaboglu, 2 March 2017

- ^ "SerraGlaze Q&A" (PDF). Sweet's Construction Catalog. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- ^ a b c Macky, Ian, "Current Manufacturers", Glassian, archived from the original on 10 October 2017

- ^ "Vault Lights in Stockton, California". glassian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Photo, 2015

- ^ a b Murdy, Justine (February 1999), "The Dirt on Areaways" (PDF), Heritage Vancouver Newsletter, vol. 8, no. 2, archived (PDF) from the original on 10 April 2016

- ^ "Loading – Cast Iron Pavement Lights". Retrieved 5 December 2019.

- ^ "Vault Lights in Amsterdam, the Netherlands". glassian. Archived from the original on 15 November 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Vault Lights in Dublin, Ireland". glassian. Archived from the original on 11 March 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Vault Lights in Dunedin, New Zealand". glassian. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ "Faded London: Lightwells and their variants". Faded-london.blogspot.ca. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ Robinson, Sam (19 June 2013), "Diffused Down Below: Philadelphia's Lost Vault Lights", Hiddencity Philadelphia, archived from the original on 23 October 2017

- ^ "cyclotram: like amethysts beneath my feet". cyclotram. November 2006.

- ^ "Sidewalks Part Five: Purple Glass Prisms Hidden in plain site [sic]". Historic Preservation Club. 22 January 2012.

- ^ "Vault Lights in Pretoria, South Africa". glassian. Archived from the original on 1 April 2016. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ^ a b Chris Lehman. "Historians Explore Salem's Underground". OPB. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ a b "Historians explore tunnels beneath Salem". OregonLive.com. 20 October 2010. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ "Salem's underground history on display". Statesman Journal. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ Ian Macky. "Vault Lights in San Diego, California". glassian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Jones, Shayne (1 June 2023). "These overlooked SF artifacts could completely disappear one day". SFGATE. Retrieved 9 June 2023.

- ^ a b c Hagemoen, Christine (13 April 2016), Sidewalk prisms of Vancouver, Vanalogue, archived from the original on 4 October 2017

- ^ David Hutton (30 November 2011). "Group wants to save sidewalk prism lights". Saskatoon StarPhoenix. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Greg Pender, The StarPhoenix (13 April 2015). "Purple glass prisms inset in the sidewalk on 21st Street East in front of the Urban Oasis Tower are seen, Monday, April 13, 2015. Tunnels under the area are scheduled to be infilled". Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ^ Ian Macky. "Vault Lights in Tijuana, Mexico". glassian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Matthew Blackett (5 January 2010). "Vault lights are more than sidewalk decor". Spacing Magazine. Archived from the original on 23 October 2017. Retrieved 22 October 2017.

- ^ Morrison, Andrew (19 October 2015), "The Purple Lights Of Our Ancient Basements", Scout Vancouver, archived from the original on 4 October 2017

- ^ Knopp, Samantha, Purple City – A Little History of Vancouver's Vault Lights, Artists Walking Home Project, archived from the original on 4 October 2017

- ^ "Vault Lights at the NDSD in Devils Lake, North Dakota". glassian. Retrieved 3 December 2017.