Patience (opera)

Patience; or, Bunthorne's Bride, is a comic opera in two acts with music by Arthur Sullivan and libretto by W. S. Gilbert. The opera is a satire on the aesthetic movement of the 1870s and '80s in England and, more broadly, on fads, superficiality, vanity, hypocrisy and pretentiousness; it also satirises romantic love, rural simplicity and military bluster.

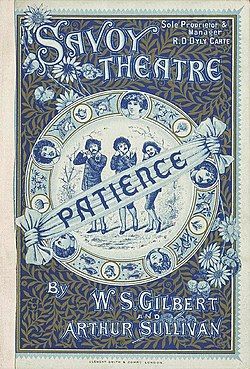

First performed at the Opera Comique, London, on 23 April 1881, Patience moved to the 1,292-seat Savoy Theatre on 10 October 1881, where it was the first theatrical production in the world to be lit entirely by electric light. Henceforth, the Gilbert and Sullivan comic operas would be known as the Savoy Operas, and both fans and performers of Gilbert and Sullivan would come to be known as "Savoyards."

Patience was the sixth operatic collaboration of fourteen between Gilbert and Sullivan. It ran for a total of 578 performances, which was seven more than the authors' earlier work, H.M.S. Pinafore, and the second longest run of any work of musical theatre up to that time, after the operetta Les Cloches de Corneville.[1]

Background

[edit]

The opera is a satire on the aesthetic movement of the 1870s and '80s in England, part of the 19th-century European movement that emphasised aesthetic values over moral or social themes in literature, fine art, the decorative arts, and interior design. Called "Art for Art's Sake", the movement valued its ideals of beauty above any pragmatic concerns.[2] Although the output of poets, painters and designers was prolific, some argued that the movement's art, poetry and fashion was empty and self-indulgent.[3][4] That the movement was so popular and also so easy to ridicule as a meaningless fad helped make Patience a big hit. The same factors made a hit out of The Colonel, a play by F. C. Burnand based partly on the satiric cartoons of George du Maurier in Punch magazine. The Colonel beat Patience to the stage by several weeks, but Patience outran Burnand's play. According to Burnand's 1904 memoir, Sullivan's friend the composer Frederic Clay leaked to Burnand the information that Gilbert and Sullivan were working on an "æsthetic subject", and so Burnand raced to produce The Colonel before Patience opened.[5][6] Modern productions of Patience have sometimes updated the setting of the opera to an analogous era such as the hippie 1960s, making a flower-child poet the rival of a beat poet.[7]

The two poets in the opera are given to reciting their own verses aloud, principally to the admiring chorus of rapturous maidens. The style of poetry Bunthorne declaims strongly contrasts with Grosvenor's. The former's, emphatic and obscure, bears a marked resemblance to Swinburne's poetry in its structure, style and heavy use of alliteration.[8] The latter's "idyllic" poetry, simpler and pastoral, echoes elements of Coventry Patmore and William Morris.[9] Gilbert scholar Andrew Crowther comments, "Bunthorne was the creature of Gilbert's brain, not just a caricature of particular Aesthetes, but an original character in his own right."[10] The makeup and costume adopted by the first Bunthorne, George Grossmith, used Swinburne's velvet jacket, the painter James McNeill Whistler's hairstyle and monocle, and knee-breeches like those worn by Oscar Wilde and others.[11]

According to Gilbert's biographer Edith Browne, the title character, Patience, was made up and costumed to resemble the subject of a Luke Fildes painting.[12] Patience was not the first satire of the aesthetic movement played by Richard D'Oyly Carte's company at the Opera Comique. Grossmith himself had written a sketch in 1876 called Cups and Saucers that was revived as a companion piece to H.M.S. Pinafore in 1878, which was a satire of the blue pottery craze.[13]

A popular misconception holds that the central character of Bunthorne, a "Fleshly Poet," was intended to satirise Oscar Wilde, but this identification is retrospective.[10] According to some authorities, Bunthorne is inspired partly by the poets Algernon Charles Swinburne and Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who were considerably more famous than Wilde in early 1881 before Wilde published his first volume of poetry.[10] Rossetti had been attacked for immorality by Robert Buchanan (under the pseudonym "Thomas Maitland") in an article called "The Fleshly School of Poetry", published in The Contemporary Review for October 1871, a decade before Patience.[14] Nonetheless, Wilde's biographer Richard Ellmann suggests that Wilde is a partial model for both Bunthorne and his rival Grosvenor.[11] Carte, the producer of Patience, was also Wilde's booking manager in 1881 as the poet's popularity took off. In 1882, after the New York production of Patience opened, Carte sent Wilde on a yearlong US lecture tour, with his knee breeches, long hair and other idiosyncratic styling, to discuss poetry and the English aesthetic movement, intending to help popularise the show's American touring productions.[10][15]

Although a satire of the aesthetic movement is dated today, fads and hero-worship are evergreen, and "Gilbert's pen was rarely sharper than when he invented Reginald Bunthorne".[2] Gilbert originally conceived Patience as a tale of rivalry between two curates and of the doting women who attended upon them. The plot and even some of the dialogue were lifted straight out of Gilbert's Bab Ballad "The Rival Curates". While writing the libretto, however, Gilbert took note of the criticism he had received for his very mild satire of a clergyman in The Sorcerer, and looked about for an alternative pair of rivals. Some remnants of the Bab Ballad version do survive in the final text of Patience. Lady Jane advises Bunthorne to tell Grosvenor: "Your style is much too sanctified – your cut is too canonical!" Later, Grosvenor agrees to change his lifestyle by saying, "I do it on compulsion!" – the very words used by the Reverend Hopley Porter in the Bab Ballad. Gilbert's selection of aesthetic poet rivals proved to be a fertile subject for topsy-turvy treatment. He both mocks and joins in Buchanan's criticism of what the latter calls the poetic "affectations" of the "fleshly school" – their use of archaic terminology, archaic rhymes, the refrain, and especially their "habit of accenting the last syllable in words which in ordinary speech are accented on the penultimate." All of these poetic devices or "mediaevalism's affectations", as Bunthorne calls them, are parodied in Patience. For example, accenting the last syllable of "lily" and rhyming it with "die" parodies two of these devices at once.[16]

On 10 October 1881, during its original run, Patience transferred to the new Savoy Theatre, the first public building in the world lit entirely by electric light.[17][18] Carte explained why he had introduced electric light: "The greatest drawbacks to the enjoyment of the theatrical performances are, undoubtedly, the foul air and heat which pervade all theatres. As everyone knows, each gas-burner consumes as much oxygen as many people, and causes great heat beside. The incandescent lamps consume no oxygen, and cause no perceptible heat."[19] When the electrical system was ready for full operation, in December 1881, Carte stepped on stage to demonstrate the safety of the new technology by breaking a glowing lightbulb before the audience.[20]

Roles

[edit]

- Colonel Calverley (Officer of Dragoon Guards) (bass-baritone)

- Major Murgatroyd (Officer of Dragoon Guards) (baritone)

- Lieut. The Duke of Dunstable (Officer of Dragoon Guards) (tenor)

- Reginald Bunthorne (a Fleshly Poet) (comic baritone)

- Archibald Grosvenor (an Idyllic Poet) (lyric baritone)

- Mr. Bunthorne's Solicitor (silent)

- The Lady Angela (Rapturous Maiden) (mezzo-soprano)

- The Lady Saphir (Rapturous Maiden) (mezzo-soprano or soprano)

- The Lady Ella (Rapturous Maiden) (soprano)

- The Lady Jane (Rapturous Maiden) (contralto)

- Patience (a Dairy Maid) (soprano)

- Chorus of Rapturous Maidens and Officers of Dragoon Guards

Synopsis

[edit]

- Act I

In front of Castle Bunthorne, a group of "lovesick maidens" are all in love with the aesthetic poet Bunthorne ("Twenty lovesick maidens we"). Lady Jane, the oldest and plainest of them, announces that Bunthorne, far from returning their affections, has his heart set on the simple milkmaid Patience. Patience appears and confesses that she has never loved anyone; she is thankful that love has not turned her miserable as it has them ("I cannot tell what this love may be"). Soon, the lovesick maidens' old sweethearts, the 35th Dragoon Guards, appear ("The soldiers of our Queen"), led by Colonel Calverley ("If you Want a Receipt for that Popular Mystery"), Major Murgatroyd, and the ordinary but immensely rich Lieutenant the Duke of Dunstable. They arrive ready to propose marriage, only to discover their intendeds fawning over Bunthorne, who is in the throes of poetical composition, pretending to ignore the attention of the women thronging around him ("In a doleful train"). Bunthorne reads his poem and departs, while the officers are coldly rebuffed and mocked by their former sweethearts, who turn up their noses at the sight of their red and yellow uniforms. The Dragoons, reeling from the insult, depart ("When I first put this uniform on").

Bunthorne, left alone, confesses that his aestheticism is a sham and mocks the movement's pretensions ("If you're anxious for to shine"). Seeing Patience, he reveals that, like her, he does not like poetry, but she tells him that she cannot love him. Later, Lady Angela, one of Bunthorne's admirers, explores with Patience the latter's childhood crush ("Long years ago"). Lady Angela rhapsodises upon love as the one truly unselfish pursuit in the world. Impressed by her eloquence, Patience promises to fall in love at the earliest opportunity. Serendipitously, Archibald Grosvenor arrives; he is another aesthetic poet who turns out to be Patience's childhood love. He has grown to be the infallible, widely loved "Archibald the All-Right" ("Prithee, pretty maiden"). The two declare themselves in love but are brought up short by the realisation that as Grosvenor is a perfect being, for Patience to love him would be a selfish act, and therefore not true love; thus, they must part.

Bunthorne, heartbroken by Patience's rejection, has chosen to raffle himself off among his lady followers ("Let the merry cymbals sound"), the proceeds going to charity. The Dragoons interrupt the proceedings, and, led by the Duke, attempt to reason with the women ("Your maiden hearts, ah, do not steel"), but they are too busy clamouring for raffle tickets to listen ("Come walk up"). Just as Bunthorne is handing the bag to the unattractive Jane, ready for the worst, Patience interrupts the proceedings and proposes to unselfishly sacrifice herself by loving the poet ("True Love must single-hearted be"). A delighted Bunthorne accepts immediately, and his followers, their idol lost, return to the Dragoons to whom they are engaged ("I hear the soft note of the echoing voice"). All seems resolved until Grosvenor enters, and the women, finding him poetic, aesthetic, and far more attractive than Bunthorne, become his partisans instead ("Oh, list while we a love confess"), much to the dismay of the Dragoons, Patience, Bunthorne and especially Grosvenor himself.

Act II

Lady Jane, accompanying herself on the cello,[21] laments the passing of the years and expresses hope that Bunthorne will "secure" her before it is too late ("Silvered is the raven hair"). Meanwhile, Grosvenor wearily entertains the women ("A magnet hung in a hardware shop") and begs to be given a half-holiday from their cloying attentions. Bunthorne is furious when Patience confesses her affection for Grosvenor; she laments the bitter lesson she has learned about love ("Love is a plaintive song"). Bunthorne longs to regain his former admirers' admiration; Jane offers her assistance ("So go to him, and say to him"). The Dragoon officers attempt to earn their partners' love by appearing to convert to the principles of aestheticism ("It's clear that mediaeval art"). Angela and Saphir are favourably impressed and accept Calverly and Murgatroyd in matrimony; Dunstable graciously bows out ("If Saphir I choose to marry").

Bunthorne threatens Grosvenor with a dire curse unless he undertakes to become perfectly commonplace. Intimidated, and also pleased at the excuse to escape the celebrity caused by his "fatal beauty", Grosvenor agrees ("When I go out of door"). This plot backfires, however, when Grosvenor reappears as an ordinary man; the women follow him into ordinariness, becoming "matter-of-fact young girls." Patience realises that Grosvenor has lost his perfection, and so it will no longer be selfish for her to marry him, which she undertakes to do without delay. The women, following suit, return to their old fiancés among the Dragoons. In the spirit of fairness, Dunstable chooses the "plain" Lady Jane as his bride for her very lack of appeal. Bunthorne is left with the "vegetable love" that he had (falsely) claimed to desire. Thus, "Nobody [is] Bunthorne's bride."

Musical numbers

[edit]- Overture (includes "Turn, oh turn, in this direction", "So go to him and say to him", and "Oh list while we a love confess"). The Overture was prepared by Eugen d'Albert, who was then a pupil of Sullivan's, based on Sullivan's sketch.[22]

- Act I

- 1. "Twenty love-sick maidens we" (Angela, Ella and Chorus of Maidens)

- 2. "Still brooding on their mad infatuation" (Patience, Saphir, Angela, and Chorus)

- 2a. "I cannot tell what this love may be" (Patience and Chorus)

- 2b. "Twenty love-sick maidens we" (Chorus of Maidens – Exit)

- 3. "The soldiers of our Queen" (Chorus of Dragoons)

- 3a. "If you want a receipt for that popular mystery" (Colonel and Chorus)1

- 4. "In a doleful train two and two we walk" (Angela, Ella, Saphir, Bunthorne, and Chorus of Maidens and Dragoons)

- 4a. "Twenty love-sick maidens we" (Chorus of Maidens – Exit)

- 5. "When I first put this uniform on" (Colonel and Chorus of Dragoons)

- 6. "Am I alone and unobserved?" (Bunthorne)

- 7. "Long years ago, fourteen maybe" (Patience and Angela)

- 8. "Prithee, pretty maiden" (Patience and Grosvenor)

- 8a. "Though to marry you would very selfish be" (Patience and Grosvenor)

- 9. "Let the merry cymbals sound" (Ensemble)

1 This was originally followed by a song for the Duke, "Though men of rank may useless seem." The orchestration survives in Sullivan's autograph score, but without a vocal line. There have been several attempts at a reconstruction, including one by David Russell Hulme that was included on the 1994 new D'Oyly Carte Opera Company recording.

- Act II

- 10. "On such eyes as maidens cherish" (Chorus of Maidens)

- 11. "Sad is that woman's lot" (Jane)

- 12. "Turn, oh turn, in this direction" (Chorus of Maidens)

- 13. "A magnet hung in a hardware shop" (Grosvenor and Chorus of Maidens)

- 14. "Love is a plaintive song" (Patience)

- 15. "So go to him, and say to him" (Jane and Bunthorne)

- 16. "It's clear that mediaeval art" (Duke, Major, and Colonel)

- 17. "If Saphir I choose to marry" (Angela, Saphir, Duke, Major, and Colonel)

- 18. "When I go out of door" (Bunthorne and Grosvenor)

- 19. "I'm a Waterloo House young man" (Grosvenor and Chorus of Maidens)

- 20. "After much debate internal" (Ensemble)

Note on topical references: Songs and dialogue in Patience contain many topical references to persons and events of public interest in 1881. In particular, the Colonel's song, Act I, item 3a above, is almost entirely composed of such references. The Wikisource text of the opera contains links explaining these references.

Production history

[edit]

The original run of Patience in London, split across two theatres, was the second longest of the Gilbert and Sullivan series, eclipsed only by The Mikado. The original sets were designed by John O'Connor.[23] Its first London revival was in 1900, making it the last of the revivals for which all three partners (Gilbert, Sullivan, and D'Oyly Carte) were alive. At that time, Gilbert admitted some doubts as to whether the æsthetic subject would still be appreciated, years after the fad had died out. Gilbert wrote to Sullivan after the premiere of this revival (which the composer was too ill to attend), "The old opera woke up splendidly."[24]

In the British provinces, Patience played – either by itself, or in repertory – continuously from summer 1881 to 1885, then again in 1888. It rejoined the touring repertory in 1892 and was included in every season until 1955–56. New costumes were designed in 1907 by Percy Anderson, in 1918 by Hugo Rumbold and in 1928 by George Sheringham, who also designed a new set that year. New designs by Peter Goffin debuted in 1957.[23] The opera returned to its regular place in the repertory, apart from a break in 1962–63. Late in the company's history, it toured a reduced set of operas to reduce costs. Patience had its final D'Oyly Carte performances in April 1979 and was left out of the company's last three seasons of touring.[25]

In America, Richard D'Oyly Carte mounted a production at the Standard Theatre in September 1881, six months after the London premiere. One of the "pirated" American productions of Patience starred the young Lillian Russell.[26] In Australia, the opera's first authorised performance was on 26 November 1881 at the Theatre Royal, Sydney, produced by J. C. Williamson.[citation needed]

Patience entered the repertory of the English National Opera in 1969, in an acclaimed production with Derek Hammond-Stroud as Bunthorne. The production was later mounted in Australia and was preserved on video as part of the Brent Walker series. In 1984, ENO also took the production on tour to the Metropolitan Opera House, in New York City.[27]

The following table shows the history of the D'Oyly Carte productions in Gilbert's lifetime:[28]

| Theatre | Opening Date | Closing Date | Perfs. | Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opera Comique | 23 April 1881 | 8 October 1881 | 170 | |

| Savoy Theatre | 10 October 1881 | 22 November 1882 | 408 | |

| Standard Theatre, New York | 22 September 1881 | 23 March 1882 | 177 | Authorised American production |

| Savoy Theatre | 7 November 1900 | 20 April 1901 | 150 | First London revival |

| Savoy Theatre | 4 April 1907 | 24 August 1907 | 51 | First Savoy repertory season; played with three other operas. Closing date shown is of the entire season. |

Historical casting

[edit]The following tables show the casts of the principal original productions and D'Oyly Carte Opera Company touring repertory at various times through to the company's 1982 closure:

| Role | Opera Comique 1881[29] |

Standard Theatre 1881[30][31] |

Savoy Theatre 1900[32] |

Savoy Theatre 1907[33] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonel | Richard Temple[34] | William T. Carleton | Jones Hewson | Frank Wilson |

| Major | Frank Thornton | Arthur Wilkinson | W. H. Leon | Richard Andean |

| Duke | Durward Lely | Llewellyn Cadwaladr | Robert Evett | Harold Wilde |

| Bunthorne | George Grossmith | J. H. Ryley | Walter Passmore | Charles H. Workman |

| Grosvenor | Rutland Barrington | James Barton Key | Henry Lytton | John Clulow |

| Solicitor | George Bowley | William White | H. Carlyle Pritchard | Ronald Greene |

| Angela | Jessie Bond | Alice Burville | Blanche Gaston-Murray | Jessie Rose |

| Saphir | Julia Gwynne | Rose Chapelle | Lulu Evans | Marie Wilson |

| Ella | May Fortescue | Alma Stanley | Agnes Fraser | Ruby Gray |

| Jane | Alice Barnett | Augusta Roche | Rosina Brandram | Louie René |

| Patience | Leonora Braham | Carrie Burton | Isabel Jay | Clara Dow |

| Role | D'Oyly Carte 1915 Tour[35] |

D'Oyly Carte 1925 Tour[36] |

D'Oyly Carte 1935 Tour[37] |

D'Oyly Carte 1945 Tour[38] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonel | Frederick Hobbs | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt | Darrell Fancourt |

| Major | Allen Morris | Martyn Green | Frank Steward | C. William Morgan |

| Duke | Dewey Gibson | Charles Goulding | John Dean | Herbert Garry |

| Bunthorne | Henry Lytton | Henry Lytton | Martyn Green | Grahame Clifford |

| Grosvenor | Leicester Tunks | Henry Millidge | Leslie Rands | Leslie Rands |

| Solicitor | E. A. Cotton | Alex Sheahan | W. F. Hodgkins | Ernest Dale |

| Angela | Nellie Briercliffe | Aileen Davies | Marjorie Eyre | Marjorie Eyre |

| Saphir | Ella Milne | Beatrice Elburn | Elizabeth Nickell-Lean | Doreen Binnion |

| Ella | Phyllis Smith | Irene Hill | Margery Abbott | Rosalie Dyer |

| Jane | Bertha Lewis | Bertha Lewis | Dorothy Gill | Ella Halman |

| Patience | Elsie McDermid | Winifred Lawson | Doreen Denny | Margery Abbott |

| Role | D'Oyly Carte 1950 Tour[39] |

D'Oyly Carte 1957 Tour[40] |

D'Oyly Carte 1965 Tour[41] |

D'Oyly Carte 1975 Tour[42] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colonel | Darrell Fancourt | Donald Adams | Donald Adams | John Ayldon |

| Major | Peter Pratt | John Reed | Alfred Oldridge | James Conroy-Ward |

| Duke | Leonard Osborn | Leonard Osborn | Philip Potter | Meston Reid |

| Bunthorne | Martyn Green | Peter Pratt | John Reed | John Reed |

| Grosvenor | Alan Styler | Arthur Richards | Kenneth Sandford | Kenneth Sandford |

| Solicitor | Ernest Dale | Wilfred Stelfox | Jon Ellison | Jon Ellison |

| Angela | Joan Gillingham | Beryl Dixon | Peggy Ann Jones | Judi Merri |

| Saphir | Joyce Wright | Elizabeth Howarth | Pauline Wales | Patricia Leonard |

| Ella | Muriel Harding | Jean Hindmarsh | Valerie Masterson | Rosalind Griffiths |

| Jane | Ella Halman | Ann Drummond-Grant | Christene Palmer | Lyndsie Holland |

| Patience | Margaret Mitchell | Cynthia Morey[43] | Ann Hood | Pamela Field |

Recordings

[edit]

Of the recordings of this opera, the 1961 D'Oyly Carte Opera Company recording (with complete dialogue) has been the best received. Two videos, Brent Walker (1982) and Australian Opera (1995), are both based on the respected English National Opera production first seen in the 1970s.[44] A D'Oyly Carte production was broadcast on BBC2 television on 27 December 1965, but the recording is believed lost.[45] Several professional productions have been recorded on video by the International Gilbert and Sullivan Festival since 2000.[46]

- Selected recordings

- 1930 D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: Malcolm Sargent[47]

- 1951 D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[48]

- 1961 D'Oyly Carte (with dialogue) – New Symphony Orchestra of London; Conductor: Isidore Godfrey[49]

- 1962 Sargent/Glyndebourne – Pro Arte Orchestra, Glyndebourne Festival Chorus; Conductor: Sir Malcolm Sargent[50]

- 1982 Brent Walker Productions (video) – Ambrosian Opera Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra; Conductor: Alexander Faris; Stage Director: John Cox[51]

- 1994 New D'Oyly Carte – Conductor: John Owen Edwards[52]

- 1995 Australian Opera (video) – Conductor: David Stanhope; Stage Director: John Cox[53]

Oscar Brand and Joni Mitchell recorded "Prithee Pretty Maiden" for the Canadian folk music TV program Let's Sing Out, broadcast by CBC Television in 1966.[54]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Les Cloches de Corneville was the longest-running work of musical theatre in history, until Dorothy in 1886. See this article on longest runs in the theatre up to 1920

- ^ a b Smith, Steve. "A Satire With Targets Not So Well Remembered", The New York Times, 5 January 2014

- ^ Fargis, p. 261

- ^ Denney, p. 38

- ^ Burnand, p. 165

- ^ In fact, many stage works prior to 1881 had satirised the aesthetic craze. A review of Patience in The Illustrated London News noted: "By this time the [English] stage is thickly sown all over with a crop of lilies and sunflowers". June 18, 1881, p. 598, discussed and quoted in Williams, pp. 153–54.

- ^ Bradley, 2005

- ^ Jones, p. 46; Williams, p. 179

- ^ Jones, pp. 48–52

- ^ a b c d Crowther, Andrew. "Bunthorne and Oscar Wilde", The Gilbert and Sullivan Archive, 8 June 2009

- ^ a b Ellmann, pp. 135 and 151–52

- ^ Browne, p. 93, identifies Fildes's "first successful painting", "Where are you going to, my pretty maid?"; Browne may have meant the Fildes painting of the milk maid "Betty": Image of "Betty" in Thompson, David Croal. The Life & Work of Luke Fildes, R.A., J. S. Virtue & Co. (1895), p. 23

- ^ Cups and Saucers, the Gilbert and Sullivan Archive

- ^ In the essay, Buchanan excoriates Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite school for elevating sensual, physical love to the level of the spiritual.

- ^ Cooper, John. "The Lecture Tour of North America 1882", Oscar Wilde in America, retrieved 29 October 2023; and "Oscar Wilde's Lecture", The New York Times, 10 January 1882, p. 5

- ^ Williams, p. 175, discussing the parody of poetic styles in Patience, including Gilbert's satiric use of the poetic devices criticised in Robert Williams Buchanan's essay "The Fleshly School of Poetry", The Contemporary Review, October 1871.

- ^ See this article on the Savoy Theatre from arthurlloyd.co.uk, retrieved 20 July 2007. See also this article from the Ambassador Theatre Group Limited

- ^ Burgess, Michael. "Richard D'Oyly Carte", The Savoyard, January 1975, pp. 7–11

- ^ "Richard D'Oyly Carte" Archived 13 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, at the Lyric Opera San Diego website, June 2009

- ^ Description of lightbulb experiment in The Times, 28 December 1881

- ^ "Violoncello" is specified in the original libretto, though in the original production a double bass was used (see Alice Barnett photograph), an instrument specified in the licence copy and first American libretto of the opera. Subsequent productions have varied in their choice of cello, double bass or a similar prop. See photographs of past D'Oyly Carte productions and this photo from Peter Goffin's D'Oyly Carte production.

- ^ Hulme, pp. 242–243; and Ainger, p. 195

- ^ a b Rollins and Witts, Appendix, p. VII

- ^ Allen 1975, p. 461

- ^ Rollins and Witts, supplements

- ^ Information about, and programmes for, American and other productions of Patience Archived 10 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ During his term of office, Chief Justice William Rehnquist, a great Gilbert and Sullivan fan, played the silent role of Mr. Bunthorne's Solicitor in a 1985 Washington Savoyards production of the piece. See Garcia, Guy D. (2 June 1986). "People". Time. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011. Retrieved 17 August 2007.

- ^ Rollins and Witts, pp. 8–21

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 8

- ^ Gänzl, p. 187

- ^ Brown, Thomas Allston (1903). A history of the New York stage from the first performance in 1732 to 1901. New York: Dodd, Mead and company. p. 246.. Retrieved 14 September 2010.

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 19

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 21

- ^ Temple was replaced in the role on 8 October 1881, the last night at the Opera Comique, by Walter Browne. See the classified ad for Patience in The Times, 8 October 1881, p. 6. Temple remained at the Opera Comique to play King Portico in Princess Toto when John Hollingshead took over the management of that theatre from Carte. See "Opera Comique", The Times, 18 October 1881, p. 4.

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 132

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 148

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 160

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 170

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 175

- ^ Rollins and Witts, p. 182

- ^ Rollins and Witts, 1st Supplement, p. 7

- ^ Rollins and Witts, 3rd Supplement, p. 28

- ^ Morey is President of the Gilbert and Sullivan Society in London. See also Ffrench, Andrew. "Retired opera singer Cynthia Morey lands 'yum' film role in Quartet", Oxford Mail, 2 February 2013

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "Recordings of Patience", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 5 April 2003, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The 1965 D'Oyly Carte Patience Broadcast", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 5 April 2003, retrieved 30 October 2017

- ^ "Professional Shows from the Festival" Archived 26 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Musical Collectibles catalogue website, retrieved 15 October 2012

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The 1930 D'Oyly Carte Patience", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 8 September 2008, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The 1951 D'Oyly Carte Patience", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 11 July 2009, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The 1961 D'Oyly Carte Patience", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 8 September 2008, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The Sargent/EMI Patience (1962)", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 16 November 2001, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The Brent Walker Patience (1982)", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 5 April 2009, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The New D'Oyly Carte Patience (1994)", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 8 September 2008, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ Shepherd, Marc. "The Opera Australia Patience (1995)", The Gilbert and Sullivan Discography, 13 April 2009, retrieved 2 August 2016

- ^ "Prithee, Pretty Maiden", JoniMitchell.com, retrieved 21 June 2015

References

[edit]

- Ainger, Michael (2002). Gilbert and Sullivan – A Dual Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514769-8.

- Allen, Reginald (1975). The First Night Gilbert and Sullivan. London: Chappell & Co. Ltd. ISBN 978-0-903443-10-4.

- Baily, Leslie (1952). The Gilbert & Sullivan Book. London: Cassell & Company Ltd. OCLC 557872459.

- Bradley, Ian C. (2005). Oh Joy! Oh Rapture! The Enduring Phenomenon of Gilbert and Sullivan. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-516700-9.

- Browne, Edith A. (1907). Stars of the Stage: W. S. Gilbert. London: the Bodley Head. OCLC 150457714.

- Burnand, Francis C. (1904). Records and Reminiscences : Personal and General. London: Methuen. OCLC 162966824.

- Denney, Colleen (2000). At the Temple of Art: the Grosvenor Gallery, 1877-1890. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-3850-7.

- Ellmann, Richard (1988). Oscar Wilde. New York: Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-55484-6.

- Fargis, Paul (1998). The New York Public Library Desk Reference (3rd ed.). London: Macmillan General Reference. ISBN 978-0-02-862169-2.

- Gänzl, Kurt (1986). The British Musical Theatre – Volume I, 1865–1914. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-520509-1.

- Hulme, David Russell (1986). The Operettas of Sir Arthur Sullivan – Volume I (PhD thesis). Aberystwyth University. hdl:2160/7735.

- Jones, John B. (Winter 1965). "In Search of Archibald Grosvenor: A New Look at Gilbert's "Patience"". Victorian Poetry. 3 (1). West Virginia University Press: 45–53. JSTOR 40001289. (subscription required)

- Rollins, Cyril; R. John Witts (1962). The D'Oyly Carte Opera Company in Gilbert and Sullivan Operas: A Record of Productions, 1875–1961. London: Michael Joseph. OCLC 504581419. Also, five supplements, privately printed.

- Willilams, Carolyn (2010). Gilbert and Sullivan: Gender, Genre, Parody. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14804-7.

External links

[edit]- Patience at The Gilbert & Sullivan Archive

- Complete downloadable vocal score

- Patience at The Gilbert & Sullivan Discography

- NY Times review of original NY production

- Souvenir Programme marking the 250th performance of Patience in 1881

- Biographies of the people listed in the historical casting chart

- Posters from the original American production

Patience public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Patience public domain audiobook at LibriVox