Pasta

A collection of different pasta varieties | |

| Type | Staple ingredient for many dishes |

|---|---|

| Place of origin | Italy |

| Main ingredients | Durum wheat flour |

| Ingredients generally used | Water, sometimes eggs |

| Variations | Rice flour pasta, legume pasta |

Pasta (UK: /ˈpæstə/, US: /ˈpɑːstə/; Italian: [ˈpasta]) is a type of food typically made from an unleavened dough of wheat flour mixed with water or eggs, and formed into sheets or other shapes, then cooked by boiling or baking. Pasta was originally only made with durum, although the definition has been expanded to include alternatives for a gluten-free diet, such as rice flour, or legumes such as beans or lentils. Pasta is believed to have developed independently in Italy and is a staple food of Italian cuisine,[1][2] with evidence of Etruscans making pasta as early as 400 BCE in Italy.[3][4]

Pastas are divided into two broad categories: dried (Italian: pasta secca) and fresh (Italian: pasta fresca). Most dried pasta is produced commercially via an extrusion process, although it can be produced at home. Fresh pasta is traditionally produced by hand, sometimes with the aid of simple machines.[5] Fresh pastas available in grocery stores are produced commercially by large-scale machines.

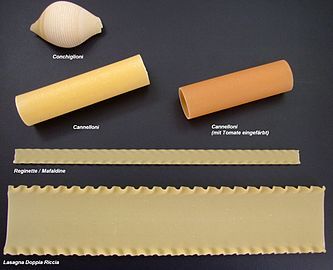

Both dried and fresh pastas come in a number of shapes and varieties, with 310 specific forms known by over 1,300 documented names.[6] In Italy, the names of specific pasta shapes or types often vary by locale. For example, the pasta form cavatelli is known by 28 different names depending upon the town and region. Common forms of pasta include long and short shapes, tubes, flat shapes or sheets, miniature shapes for soup, those meant to be filled or stuffed, and specialty or decorative shapes.[7]

As a category in Italian cuisine, both fresh and dried pastas are classically used in one of three kinds of prepared dishes: as pasta asciutta (or pastasciutta), cooked pasta is plated and served with a complementary sauce or condiment; a second classification of pasta dishes is pasta in brodo, in which the pasta is part of a soup-type dish. A third category is pasta al forno, in which the pasta is incorporated into a dish that is subsequently baked in the oven.[8] Pasta dishes are generally simple, but individual dishes vary in preparation. Some pasta dishes are served as a small first course or for light lunches, such as pasta salads. Other dishes may be portioned larger and used for dinner. Pasta sauces similarly may vary in taste, color and texture.[9]

In terms of nutrition, cooked plain pasta is 31% carbohydrates (mostly starch), 6% protein, and low in fat, with moderate amounts of manganese, but pasta generally has low micronutrient content. Pasta may be enriched or fortified, or made from whole grains.

Etymology

Earliest appearances in the English language are in the 1830s;[10][11] the word pasta comes from Italian pasta, in turn from Latin pasta, latinisation of the Ancient Greek: παστά.[citation needed]

History

Evidence of Etruscans making pasta dates back to 400 BCE.[3] The first concrete information on pasta products in Italy dates to the 13th or 14th centuries.[13] In the 1st century AD[dubious – discuss] writings of Horace, lagana (sg.: laganum) were fine sheets of fried dough[14] and were an everyday foodstuff.[15] Writing in the 2nd century, Athenaeus of Naucratis provides a recipe for lagana which he attributes to the 1st century Chrysippus of Tyana: sheets of dough made of wheat flour and the juice of crushed lettuce, then flavored with spices and deep-fried in oil.[15] An early 5th century cookbook describes a dish called lagana that consisted of layers of dough with meat stuffing, an ancestor of modern-day lasagna.[15] However, the method of cooking these sheets of dough does not correspond to the modern definition of either a fresh or dry pasta product, which only had similar basic ingredients and perhaps the shape.[15]

Historians have noted several lexical milestones relevant to pasta, none of which changes these basic characteristics. For example, the works of the 2nd century AD Greek physician Galen mention itrion, homogeneous compounds made of flour and water.[16] The Jerusalem Talmud records that itrium, a kind of boiled dough,[16] was common in Palestine from the 3rd to 5th centuries AD.[17] A dictionary compiled by the 9th century Arab physician and lexicographer Isho bar Ali[18] defines itriyya, the Arabic cognate, as string-like shapes made of semolina and dried before cooking. The geographical text of Muhammad al-Idrisi, compiled for the Norman King of Sicily Roger II in 1154 mentions itriyya manufactured and exported from Norman Sicily:

West of Termini there is a delightful settlement called Trabia [along the Sicilian coast east of Palermo]. Its ever-flowing streams propel a number of mills. Here there are huge buildings in the countryside where they make vast quantities of itriyya which is exported everywhere: to Calabria, to Muslim and Christian countries. Very many shiploads are sent.[19]

One form of itriyya with a long history is lagana, which in Latin refers to thin sheets of dough,[15] and gave rise to the Italian lasagna.

In North Africa, a food similar to pasta, known as couscous, has been eaten for centuries. However, it lacks the distinguishing malleable nature of pasta, couscous being more akin to droplets of dough. At first, dry pasta was a luxury item in Italy because of high labor costs; durum wheat semolina had to be kneaded for a long time.

There is a legend of Marco Polo importing pasta from China[20][21] which originated with the Macaroni Journal, published by an association of food industries with the goal of promoting pasta in the United States.[22] Rustichello da Pisa writes in his Travels that Marco Polo described a food similar to lagana. The way pasta reached Europe is unknown, however there are many theories, [23] Jeffrey Steingarten asserts that Moors introduced pasta in the Emirate of Sicily in the ninth century, mentioning also that traces of pasta have been found in ancient Greece and that Jane Grigson believed the Marco Polo story to have originated in the 1920s or 1930s in an advertisement for a Canadian spaghetti company.[24]

Food historians estimate that the dish probably took hold in Italy as a result of extensive Mediterranean trading in the Middle Ages. From the 13th century, references to pasta dishes—macaroni, ravioli, gnocchi, vermicelli—crop up with increasing frequency across the Italian peninsula.[25] In the 14th-century writer Boccaccio's collection of earthy tales, The Decameron, he recounts a mouthwatering fantasy concerning a mountain of Parmesan cheese down which pasta chefs roll macaroni and ravioli to gluttons waiting below.[25]

In the 14th and 15th centuries, dried pasta became popular for its easy storage. This allowed people to store pasta on ships when exploring the New World.[26] A century later, pasta was present around the globe during the voyages of discovery.[27]

Although tomatoes were introduced to Italy in the 16th century and incorporated in Italian cuisine in the 17th century, description of the first Italian tomato sauces dates from the late 18th century: the first written record of pasta with tomato sauce can be found in the 1790 cookbook L'Apicio Moderno by Roman chef Francesco Leonardi.[28] Before tomato sauce was introduced, pasta was eaten dry with the fingers; the liquid sauce demanded the use of a fork.[26]

History of manufacturing

At the beginning of the 17th century, Naples had rudimentary machines for producing pasta, later establishing the kneading machine and press, making pasta manufacturing cost-effective.[29] In 1740, a license for the first pasta factory was issued in Venice.[29] During the 1800s, watermills and stone grinders were used to separate semolina from the bran, initiating expansion of the pasta market.[29] In 1859, Joseph Topits (1824−1876) founded Hungary's first pasta factory, in the city of Pest, which worked with steam machines; it was one of the first pasta factories in Central Europe.[30] By 1867, Buitoni Company in Sansepolcro, Tuscany, was an established pasta manufacturer.[31] During the early 1900s, artificial drying and extrusion processes enabled greater variety of pasta preparation and larger volumes for export, beginning a period called "The Industry of Pasta".[29][32] In 1884, the Zátka Brothers's plant in Boršov nad Vltavou was founded, making it Bohemia's first pasta factory.[33]

In modern times

The art of pasta making and the devotion to the food as a whole has evolved since pasta was first conceptualized. In 2008, it was estimated that Italians ate over 27 kg (60 lb) of pasta per person, per year, easily beating Americans, who ate about 9 kg (20 lb) per person.[34] Pasta is so beloved in Italy that individual consumption exceeds the average production of wheat of the country; thus, Italy frequently imports wheat for pasta making. In contemporary society, pasta is ubiquitous and there is a variety of types in local supermarkets, in many countries. With the worldwide demand for this staple food, pasta is now largely mass-produced in factories and only a tiny proportion is crafted by hand.[34]

Ingredients and preparation

Since at least the time of Cato's De Agri Cultura, basic pasta dough has been made mostly of wheat flour or semolina,[6] with durum wheat used predominantly in the south of Italy and soft wheat in the north. Regionally other grains have been used, including those from barley, buckwheat, rye, rice, and maize, as well as chestnut and chickpea flours. Liquid, often in the form of eggs, is used to turn the flour into a dough.

To address the needs of people affected by gluten-related disorders (such as coeliac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity and wheat allergy sufferers),[35] some recipes use rice or maize for making pasta. Grain flours may also be supplemented with cooked potatoes.[36][37]

Other additions to the basic flour-liquid mixture may include vegetable purees such as spinach or tomato, mushrooms, cheeses, herbs, spices and other seasonings. While pastas are, most typically, made from unleavened doughs, at least nine different pasta forms are known to use yeast-raised doughs.[6]

Additives in dried, commercially sold pasta include vitamins and minerals that are lost from the durum wheat endosperm during milling. They are added back to the semolina flour once it is ground, creating enriched flour. Micronutrients added may include niacin (vitamin B3), riboflavin (vitamin B2), folate, thiamine (vitamin B1), and ferrous iron.[38]

Varieties

-

Long pasta

-

Short pasta

-

Short pasta

-

Minute pasta pastina, used for soups

-

Pasta all'uovo (lit. 'egg pasta')

-

Fresh pasta

Fresh

Fresh pasta is usually locally made with fresh ingredients unless it is destined to be shipped, in which case consideration is given to the spoilage rates of the desired ingredients such as eggs or herbs. Furthermore, fresh pasta is usually made with a mixture of eggs and all-purpose flour or "00" low-gluten flour. Since it contains eggs, it is more tender compared to dried pasta and only takes about half the time to cook.[39] Delicate sauces are preferred for fresh pasta in order to let the pasta take front stage.[40]

Fresh pastas do not expand in size after cooking; therefore, 0.7 kg (1.5 lb) of pasta are needed to serve four people generously.[39] Fresh egg pasta is generally cut into strands of various widths and thicknesses depending on which pasta is to be made (e.g., fettuccine, pappardelle, and lasagne). It is best served with meat, cheese, or vegetables to create filled pastas such as ravioli, tortellini, and cannelloni. Fresh egg pasta is well known in the Piedmont and Emilia-Romagna regions of northern Italy. In this area, dough is only made out of egg yolk and flour resulting in a very refined flavor and texture. This pasta is often served simply with butter sauce and thinly sliced truffles that are native to this region. In other areas, such as Apulia, fresh pasta can be made without eggs. The only ingredients needed to make the pasta dough are semolina flour and water, which is often shaped into orecchiette or cavatelli. Fresh pasta for cavatelli is also popular in other places including Sicily. However, the dough is prepared differently: it is made of flour and ricotta cheese instead.[41]

Dried

Dried pasta can also be defined as factory-made pasta because it is usually produced in large amounts that require large machines with superior processing capabilities to manufacture.[41] Dried pasta can be shipped further and has a longer shelf life. The ingredients required to make dried pasta include semolina flour and water. Eggs can be added for flavor and richness, but are not needed to make dried pasta. In contrast to fresh pasta, dried pasta needs to be dried at a low temperature for several days to evaporate all the moisture allowing it to be stored for a longer period. Dried pastas are best served in hearty dishes, such as ragù sauces, soups, and casseroles.[40] Once it is cooked, the dried pasta will usually grow to twice its original size. Therefore, approximately 0.5 kg (1 lb) of dried pasta serves up to four people.[39]

Culinary uses

Cooking

Pasta, whether dry or fresh, is eaten after cooking it in hot water. For Italian pasta, which is unsalted, salt is added to the cooking water. This is not the case for Asian wheat noodles, such as udon and lo mein, which are made from salty dough.[42]

In Italy, pasta is often cooked to be al dente, such that it is still firm to the bite. This is because it is then often cooked in the sauce for a short time, which makes it soften further.[43]

There are number of urban myths about how pasta should be cooked. In fact, it does not generally matter whether pasta is cooked at a lower or a higher temperature, although lower temperatures require more stirring to avoid sticking, and certain stuffed pasta, such as tortellini, break up in higher temperatures.[43] It also does not matter whether salt is added before or after bringing the water to a boil.[43] The amount of salt has no influence on cooking speed.[43]

Sauce

Pasta is generally served with some type of sauce; the sauce and the type of pasta are usually matched based on consistency and ease of eating. Northern Italian cooking uses less tomato sauce, garlic and herbs, and béchamel sauce is more common.[44] However, Italian cuisine is best identified by individual regions. Pasta dishes with lighter use of tomato are found in Trentino-Alto Adige and Emilia-Romagna regions of northern Italy.[45][46] In Bologna, the meat-based Bolognese sauce incorporates a small amount of tomato concentrate and a green sauce called pesto originates from Genoa. In central Italy, there are sauces such as tomato sauce, amatriciana, arrabbiata, and the egg-based carbonara.

Tomato sauces are also present in southern Italian cuisine, where they originated. In southern Italy more complex variations include pasta paired with fresh vegetables, olives, capers or seafood. Varieties include puttanesca, pasta alla Norma (tomatoes, eggplant and fresh or baked cheese), pasta con le sarde (fresh sardines, pine nuts, fennel and olive oil), spaghetti aglio, olio e peperoncino (lit. 'spaghetti with garlic, [olive] oil and hot chili peppers'), pasta con i peperoni cruschi (crispy peppers and breadcrumbs).[47]

Pasta can be served also in broth (pastina, or stuffed pasta, such as tortellini, cappelletti and agnolini) or in vegetable soup, typically minestrone or bean soup (pasta e fagioli).

Processing

Fresh

Ingredients to make pasta dough include semolina flour, egg, salt and water. Flour is first mounded on a flat surface and then a well in the pile of flour is created. Egg is then poured into the well and a fork is used to mix the egg and flour.[48] There are a variety of ways to shape the sheets of pasta depending on the type required. The most popular types include penne, spaghetti, and macaroni.[49]

Kitchen pasta machines, also called pasta makers, are popular with cooks who make large amounts of fresh pasta. The cook feeds sheets of pasta dough into the machine by hand and, by turning a hand crank, rolls the pasta to thin it incrementally. On the final pass through the pasta machine, the pasta may be directed through a machine 'comb' to shape of the pasta as it emerges.

Matrix and extrusion

Semolina flour consists of a protein matrix with entrapped starch granules. Upon the addition of water, during mixing, intermolecular forces allow the protein to form a more ordered structure in preparation for cooking.[50]

Durum wheat is ground into semolina flour which is sorted by optical scanners and cleaned.[51] Pipes allow the flour to move to a mixing machine where it is mixed with warm water by rotating blades. When the mixture is of a lumpy consistency, the mixture is pressed into sheets or extruded. Varieties of pasta such as spaghetti and linguine are cut by rotating blades, while pasta such as penne and fusilli are extruded. The size and shape of the dies in the extruder through which the pasta is pushed determine the shape that results. The pasta is then dried at a high temperature.[52]

Factory-manufactured

The ingredients to make dried pasta usually include water and semolina flour; egg for color and richness (in some types of pasta), and possibly vegetable juice (such as spinach, beet, tomato, carrot), herbs or spices for color and flavor. After mixing semolina flour with warm water the dough is kneaded mechanically until it becomes firm and dry. If pasta is to be flavored, eggs, vegetable juices, and herbs are added at this stage. The dough is then passed into the laminator to be flattened into sheets, then compressed by a vacuum mixer-machine to clear out air bubbles and excess water from the dough until the moisture content is reduced to 12%. Next, the dough is processed in a steamer to kill any bacteria it may contain.

The dough is then ready to be shaped into different types of pasta. Depending on the type of pasta to be made, the dough can either be cut or extruded through dies. The pasta is set in a drying tank under specific conditions of heat, moisture, and time depending on the type of pasta. The dried pasta is then packaged: Fresh pasta is sealed in a clear, airtight plastic container with a mixture of carbon dioxide and nitrogen that inhibits microbial growth and prolongs the product's shelf life; dried pastas are sealed in clear plastic or cardboard packages.[53]

Gluten-free

Gluten, the protein found in grains such as wheat, rye, spelt, and barley, contributes to protein aggregation and firm texture of a normally cooked pasta. Gluten-free pasta is produced with wheat flour substitutes, such as vegetable powders, rice, corn, quinoa, amaranth, oats and buckwheat flours.[54] Other possible gluten-free pasta ingredients may include hydrocolloids to improve cooking pasta with high heat resistance, xanthan gum to retain moisture during storage, or hydrothermally-treated polysaccharide mixtures to produce textures similar to those of wheat pasta.[54][55]

Storage

The storage of pasta depends on its processing and extent of drying.[50] Uncooked pasta is kept dry and can sit in the cupboard for a year if airtight and stored in a cool, dry area. Cooked pasta is stored in the refrigerator for a maximum of five days in an airtight container. Adding a couple teaspoons of oil helps keep the food from sticking to itself and the container. Cooked pasta may be frozen for up to two or three months. Should the pasta be dried completely, it can be placed back in the cupboard.[56]

Science

Molecular and physical composition

Pasta exhibits a random molecular order rather than a crystalline structure.[57] The moisture content of dried pasta is typically around 12%,[58] indicating that dried pasta will remain a brittle solid until it is cooked and becomes malleable. The cooked product is, as a result, softer, more flexible, and chewy.[57]

Semolina flour is the ground endosperm of durum wheat,[51] producing granules that absorb water during heating and an increase in viscosity due to semi-reordering of starch molecules.[51][52]

Another major component of durum wheat is protein which plays a large role in pasta dough rheology.[59] Gluten proteins, which include monomeric gliadins and polymeric glutenin, make up the major protein component of durum wheat (about 75–80%).[59] As more water is added and shear stress is applied, gluten proteins take on an elastic characteristic and begin to form strands and sheets.[59][60] The gluten matrix that results during forming of the dough becomes irreversibly associated during drying as the moisture content is lowered to form the dried pasta product.[61]

Impact of processing on physical structure

Before the mixing process takes place, semolina particles are irregularly shaped and present in different sizes.[51][62] Semolina particles become hydrated during mixing. The amount of water added to the semolina is determined based on the initial moisture content of the flour and the desired shape of the pasta. The desired moisture content of the dough is around 32% wet basis and will vary depending on the shape of pasta being produced.[62]

The forming process involves the dough entering an extruder in which the rotation of a single or double screw system pushes the dough toward a die set to a specific shape.[51] As the starch granules swell slightly in the presence of water and a low amount of thermal energy, they become embedded within the protein matrix and align along the direction of the shear caused by the extrusion process.[62]

Starch gelatinization and protein coagulation are the major changes that take place when pasta is cooked in boiling water.[59] Protein and starch competing for water within the pasta cause a constant change in structure as the pasta cooks.[62]

Production and market

In 2015–16, the largest producers of dried pasta were Italy (3.2 million tonnes), United States (2 million tonnes), Turkey (1.3 million tons), Brazil (1.2 million tonnes), and Russia (1 million tons).[63][64] In 2018, Italy was the world's largest exporter of pasta, with $2.9 billion sold, followed by China with $0.9 billion.[65]

The largest per capita consumers of pasta in 2015 were Italy (23.5 kg/person), Tunisia (16.0 kg/person), Venezuela (12.0 kg/person) and Greece (11.2 kg/person).[64] In 2017, the United States was the largest consumer of pasta with 2.7 million tons.[66]

Nutrition

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy | 660 kJ (160 kcal) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

30.9 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Starch | 26.0 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sugars | 0.6 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dietary fiber | 1.8 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

0.9 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

5.8 g | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other constituents | Quantity | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Water | 62 g | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| †Percentages estimated using US recommendations for adults,[67] except for potassium, which is estimated based on expert recommendation from the National Academies.[68] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

When cooked, plain pasta is composed of 62% water, 31% carbohydrates (26% starch), 6% protein, and 1% fat. A 100-gram (3+1⁄2 oz) portion of unenriched cooked pasta provides 670 kilojoules (160 kcal) of food energy and a moderate level of manganese (15% of the Daily Value), but few other micronutrients.

Pasta has a lower glycemic index than many other staple foods in Western culture, such as bread, potatoes, and rice.[69]

International adaptations

As pasta was introduced elsewhere in the world, it became incorporated into a number of local cuisines, which often have significantly different ways of preparation from those of Italy. When pasta was introduced to different nations, each culture would adopt a different style of preparation. In the past, ancient Romans cooked pasta-like foods by frying rather than boiling. It was also sweetened with honey or tossed with garum. Ancient Romans also enjoyed baking it in rich pies, called timballi.[70]

Africa

Countries such as Somalia, Ethiopia, and Eritrea were introduced to pasta from colonization and occupation through the Italian Empire, in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Southern Somalia has a dish called suugo which has a meat sauce, typically beef based, with their local xawaash spice mix.[71] In Ethiopia, pasta can also be served over injera, where it is also eaten with hands instead of cutlery. A dollop of bolognese with berbere spice blend can be served on the side.[72][73]

Asia

In Hong Kong, the local Chinese have adopted pasta, primarily spaghetti and macaroni, as an ingredient in the Hong Kong–style Western cuisine. In cha chaan teng, macaroni is cooked in water and served in broth with ham or frankfurter sausages, peas, black mushrooms, and optionally eggs, reminiscent of noodle soup dishes. This is often a course for breakfast or light lunch fare.[74] These affordable dining shops evolved from American food rations after World War II due to lack of supplies, and they continue to be popular for people with modest means.

Two common spaghetti dishes served in Japan are the Bolognese and the Naporitan.

In Nepal, macaroni has been adopted and cooked in a Nepalese way. Boiled macaroni is sautéed along with cumin, turmeric, finely chopped green chillies, onions and cabbage.[75]

In the Philippines, spaghetti is often served with a distinct, slightly sweet yet flavorful meat sauce (based on tomato sauce or paste and ketchup), frequently containing ground beef or pork and diced hot dogs and ham. It is spiced with soy sauce, heavy quantities of garlic, dried oregano sprigs and sometimes with dried bay leaf, and topped with grated cheese. Other pasta dishes are also cooked nowadays in Filipino kitchens, such as carbonara, pasta with alfredo sauce, and baked macaroni. These dishes are often cooked for gatherings and special occasions, such as family reunions or Christmas. Macaroni or other tube pasta is also used in sopas, a local chicken broth soup.[citation needed]

Europe

In Armenia, a popular traditional pasta called arishta is first dry pan toasted so as slightly golden, and then boiled to make the pasta dish which is often topped with yogurt, butter and garlic.[76]

In Greece, hilopittes is considered one of the finest types of dried egg pasta. It is cooked either in tomato sauce or with various kinds of casserole meat. It is usually served with Greek cheese of any type.

In Sweden, spaghetti is traditionally served with köttfärssås (Bolognese sauce), which is minced meat in a thick tomato soup.

Twice a year, hundreds of people in Sardinia make a nighttime 20-mile (32 km) pilgrimage from the city of Nuoro to the village of Lula for the biannual Feast of San Francesco, where they eat what is possibly the world's rarest pasta. Su filindeu (lit. 'threads of God' in the Sardinian language) is an incredibly intricate semolina pasta made by just three women who only make the pasta for the festival.[77]

South America

Pasta is also widespread in the Southern Cone, as well most of the rest of Brazil, mostly pervasive in the areas with mild to strong Italian roots, such as Central Argentina, and the eight southernmost Brazilian states (where macaroni is called macarrão, and more general pasta is known under the umbrella term massa, lit. 'dough', together with some Japanese noodles, such as bifum rice vermicelli and yakisoba, which also entered general taste). The local names for the pasta are many times varieties of the Italian names, such as ñoquis/nhoque for gnocchi, ravioles/ravióli for ravioli, or tallarines/talharim for tagliatelle, although some of the most popular pasta in Brazil, such as the parafuso ('screw', 'bolt'), a specialty of the country's pasta salads, are also way different both in name and format from its closest Italian relatives, in this case the fusilli.[78]

North America

In the United States, fettuccine Alfredo is a popular Italian-style dish.[79][80]

Oceania

In Australia, boscaiola sauce, based on bacon and mushrooms, is popular.[81]

Regulations

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (August 2018) |

Italy

Although numerous variations of ingredients for different pasta products are known, in Italy the commercial manufacturing and labeling of pasta for sale as a food product within the country is highly regulated.[82][83] Italian regulations recognize three categories of commercially manufactured dried pasta as well as manufactured fresh and stabilized pasta:

- Pasta, or dried pasta with three subcategories – (i.) Durum wheat semolina pasta (pasta di semola di grano duro), (ii.) Low grade durum wheat semolina pasta (pasta di semolato di grano duro) and (iii.) Durum wheat whole meal pasta (pasta di semola integrale di grano duro). Pastas made under this category must be made only with durum wheat semolina or durum wheat whole-meal semolina and water, with an allowance for up to 3% of soft-wheat flour as part of the durum flour. Dried pastas made under this category must be labeled according to the subcategory.

- Special pastas (paste speciali) – As with the pasta above, with additional ingredients other than flour and water or eggs. Special pastas must be labeled as durum wheat semolina pasta on the packaging completed by mentioning the added ingredients used (e.g., spinach). The 3% soft flour limitation still applies.

- Egg pasta (pasta all'uovo) – May only be manufactured using durum wheat semolina with at least 4 hens' eggs (chicken) weighing at least 200 grams (7.1 oz) (without the shells) per kilogram of semolina, or a liquid egg product produced only with hen's eggs. Pasta made and sold in Italy under this category must be labeled egg pasta.

- Fresh and stabilized pastas (paste alimentari fresche e stabilizzate) – Includes fresh and stabilized pastas, which may be made with soft-wheat flour without restriction on the amount. Prepackaged fresh pasta must have a water content not less than 24%, must be stored refrigerated at a temperature of not more than 4 °C (39 °F) (with a 2 °C (36 °F) tolerance), must have undergone a heat treatment at least equivalent to pasteurisation, and must be sold within five days of the date of manufacture. Stabilized pasta has a lower allowed water content of 20%, and is manufactured using a process and heat treatment that allows it to be transported and stored at ambient temperatures.

The Italian regulations under Presidential Decree No. 187 apply only to the commercial manufacturing of pastas both made and sold within Italy. They are not applicable either to pasta made for export from Italy or to pastas imported into Italy from other countries. They also do not apply to pastas made in restaurants.

United States

In the US, regulations for commercial pasta products occur both at the federal and state levels. At the Federal level, consistent with Section 341 of the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act,[84] the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has defined standards of identity for what are broadly termed macaroni products. These standards appear in 21 CFR Part 139.[85] Those regulations state the requirements for standardized macaroni products of 15 specific types of dried pastas, including the ingredients and product-specific labeling for conforming products sold in the US, including imports:

- Macaroni products – defined as the class of food prepared by drying formed units of dough made from semolina, durum flour, farina, flour, or any combination of those ingredients with water. Within this category various optional ingredients may also be used within specified ranges, including egg white, frozen egg white or dried egg white alone or in any combination; disodium phosphate; onions, celery, garlic or bay leaf, alone or in any combination; salt; gum gluten; and concentrated glyceryl monostearate. Specific dimensions are given for the shapes named macaroni, spaghetti and vermicelli.

- Enriched macaroni products – largely the same as macaroni products except that each such food must contain thiamin, riboflavin, niacin or niacinamide, folic acid and iron, with specified limits. Additional optional ingredients that may be added include vitamin D, calcium, and defatted wheat germ. The optional ingredients specified may be supplied through the use of dried yeast, dried torula yeast, partly defatted wheat germ, enriched farina, or enriched flour.

- Enriched macaroni products with fortified protein – similar to enriched macaroni products with the addition of other ingredients to meet specific protein requirements. Edible protein sources that may be used include food grade flours or meals from nonwheat cereals or oilseeds. Products in this category must include specified amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, niacin or niacinamide and iron, but not folic acid. The products in this category may also optionally contain up to 625 milligrams (9.65 gr) of calcium.

- Milk macaroni products – the same as macaroni products except that milk or a specified milk product is used as the sole moistening ingredient in preparing the dough. Other than milk, allowed milk products include concentrated milk, evaporated milk, dried milk, and a mixture of butter with skim, concentrated skim, evaporated skim, or nonfat dry milk, in any combination, with the limitation on the amount of milk solids relative to amount of milk fat.

- Nonfat milk macaroni products – the same as macaroni products except that nonfat dry milk or concentrated skim milk is used in preparing the dough. The finished macaroni product must contain between 12% and 25% milk solids-not-fat. Carageenan or carageenan salts may be added in specified amounts. The use of egg whites, disodium phosphate and gum gluten optionally allowed for macaroni products is not permitted for this category.

- Enriched nonfat milk macaroni products – similar to nonfat milk macaroni products with added requirements that products in this category contain thiamin, riboflavin, niacin or niacinamide, folic acid and iron, all within specified ranges.

- Vegetable macaroni products – macaroni products except that tomato (of any red variety), artichoke, beet, carrot, parsley or spinach is added in a quantity such that the solids of the added component are at least 3% by weight of the finished macaroni product. The vegetable additions may be in the form of fresh, canned, dried or a puree or paste. The addition of either the various forms of egg whites or disodium phosphate allowed for macaroni products is not permitted in this category.

- Enriched vegetable macaroni products – the same as vegetable macaroni products with the added requirement for nutrient content specified for enriched macaroni products.

- Whole wheat macaroni products – similar to macaroni products except that only whole wheat flour or whole wheat durum flour, or both, may be used as the wheat ingredient. Further the addition of the various forms of egg whites, disodium phosphate and gum gluten are not permitted.

- Wheat and soy macaroni products – begins as macaroni products with the addition of at least 12.5% of soy flour as a fraction of the total soy and wheat flour used. The addition the various forms of egg whites and disodium phosphate are not permitted. Gum gluten may be added with a limitation that the total protein content derived from the combination of the flours and added gluten not exceed 13%.

- Noodle products – the class of food that is prepared by drying units of dough made from semolina, durum flour, farina, flour, alone or in any combination with liquid eggs, frozen eggs, dried eggs, egg yolks, frozen yolks, dried yolks, alone or in any combination, with or without water. Optional ingredients that may be added in allowed amounts are onions, celery, garlic, and bay leaf; salt; gum gluten; and concentrated glyceryl monostearate.

- Enriched noodle products – similar to noodle products with the addition of specific requirements for amounts of thiamin, riboflavin, niacin or niacinamide, folic acid and iron, each within specified ranges. Additionally products in this category may optionally contain added vitamin D, calcium or defatted wheat germ, each within specified limits.

- Vegetable noodle products – the same as noodle products with the addition of tomato (of any red variety), artichoke, beet, carrot, parsley, or spinach in an amount that is at least 3% of the finished product weight. The vegetable component may be added as fresh, canned, dried, or in the form of a puree or paste.

- Enriched vegetable noodle products – the same as vegetable noodle products excluding carrot, with the specified nutrient requirements for enriched noodle products.

- Wheat and soy noodle products – similar to noodle products except that soy flour is added in a quantity not less than 12.5% of the combined weight of the wheat and soy ingredients.

State mandates

The federal regulations under 21 CFR Part 139 are standards for the products noted, not mandates. Following the FDA's standards, a number of states have, at various times, enacted their own statutes that serve as mandates for various forms of macaroni and noodle products that may be produced or sold within their borders. Many of these specifically require that the products sold within those states be of the enriched form.[86][87][88][89] According to a report released by the Connecticut Office of Legislative Research, when Connecticut's law was adopted in 1972 that mandated certain grain products, including macaroni products, sold within the state to be enriched it joined 38 to 40 other states in adopting the federal standards as mandates.[90]

USDA school nutrition

Beyond the FDA's standards and state statutes, the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), which regulates federal school nutrition programs,[91][92] broadly requires grain and bread products served under these programs either be enriched or whole grain (see 7 CFR 210.10 (k) (5)). This includes macaroni and noodle products that are served as part the category grains/breads requirements within those programs. The USDA also allows that enriched macaroni products fortified with protein may be used and counted to meet either a grains/breads or meat/alternative meat requirement, but not as both components within the same meal.[93]

See also

![]() Media related to Pasta at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Pasta at Wikimedia Commons

![]() The dictionary definition of pasta at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of pasta at Wiktionary

- Al dente – cooking technique

- National Pasta Association

- Pasta by Design

References

- ^ Padalino L, Conte A, Del Nobile MA (2016). "Overview on the General Approaches to Improve Gluten-Free Pasta and Bread". Foods (Review). 5 (4): 87. doi:10.3390/foods5040087. PMC 5302439. PMID 28231182.

- ^ Laleg K, Cassan D, Barron C, Prabhasankar P, Micard V (2016). "Structural, Culinary, Nutritional and Anti-Nutritional Properties of High Protein, Gluten Free, 100% Legume Pasta". PLOS ONE. 11 (9): e0160721. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1160721L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0160721. PMC 5014310. PMID 27603917.

- ^ a b Hatchett, Toby (February 26, 2008). "The saucy history of pasta". Portsmouth Herald. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Eredi, Veronica (April 27, 2023). "The history of PASTA, from the Etruscans to Dez AMORE". Dez Amore. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ Hazan, Marcella (1992) Essentials of Classic Italian Cooking, Knopf, ISBN 0-394-58404-X

- ^ a b c Zanini De Vita, Oretta, Encyclopedia of Pasta, University of California Press, ISBN 9780520255227

- ^ Hazan, Giuliano (1993) The Classic Pasta Cookbook, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 1564582922

- ^ "Pasta al Forno". Dinner at the Zoo. April 15, 2020.

- ^ Pasta. UK: Parragon Publishing. 2005. pp. 6–57. ISBN 978-1405425162.

- ^ "Pasta, N. (1), Sense 1.a." Oxford English Dictionary. July 2023. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ "Pasta". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Watson, Andrew M (1983). Agricultural innovation in the early Islamic world. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 22–23

- ^ Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 10.

- ^ Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 24.

- ^ a b c d e Serventi & Sabban 2002, pp. 15–16.

- ^ a b Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 17.

- ^ Serventi & Sabban 2002, p. 29.

- ^ "A medical text in Arabic written by a Jewish doctor living in Tunisia in the early 900s", according to Dickie, John (2008). Delizia! The Epic History of Italians and Their Food. New York: Simon and Schuster. pp. 21 ff. ISBN 978-1416554004.

- ^ Quoted in Dickie, p. 21.

- ^ "Who "invented" pasta?". National Pasta Association: "The story that it was Marco Polo who imported noodles to Italy and thereby gave birth to the country's pasta culture is the most pervasive myth in the history of Italian food." (Dickie, page 48).

- ^ "The Remnant with Jonah Goldberg - I, Nacho".

- ^ Serventi & Sabban 2002.

- ^ Uncover The History of Pasta

- ^ Jeffrey Steingarten (1998). The Man Who Ate Everything. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 260. ISBN 978-0-375-70202-0.

- ^ a b López, Alfonso (July 8, 2016). "The Twisted History of Pasta". National Geographic. Archived from the original on December 14, 2019. Retrieved December 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Walker, Margaret E. "The History of Pasta". inmamaskitchen. Archived from the original on March 31, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Demetri, Justin. "History of pasta". lifeinitaly. Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ Faccioli, Emilio (1987). L'Arte della cucina in Italia (in Italian). Milan: Einaudi. p. 756. The culí di pomodoro recipe is in the chapter devoted to Leonardi.

- ^ a b c d "History of pasta". International Pasta Organisation. 2018. Archived from the original on November 19, 2018. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "A TÉSZTÁK LEXIKONJA - TÉSZTATÖRTÉNELEM - KIFŐTT TÉSZTÁK 3. 2017.01.02 (visited - 2019. January 3.)" (in Hungarian). Archived from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- ^ "The History of Pasta: It's not what you think!". Pasta Recipes by Italians. Retrieved March 26, 2012.

- ^ Justin Demetri (May 10, 2018). "History of pasta". Life in Italy. Retrieved November 18, 2018.

- ^ "Radio Praha - THE OLDEST CZECH PASTA PLANT RELIES ON TRADITIONAL TASTE OF ITS CUSTOMERS (visited - 2019. January 3.)". September 11, 2008.

- ^ a b Demetri, Justin. "History of Pasta". Archived from the original on July 23, 2008. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ^ Vriezinga SL, Schweizer JJ, Koning F, Mearin ML (September 2015). "Coeliac disease and gluten-related disorders in childhood". Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol (Review). 12 (9): 527–36. doi:10.1038/nrgastro.2015.98. PMID 26100369. S2CID 2023530.

Gluten-related disorders such as coeliac disease, wheat allergy and noncoeliac gluten sensitivity are increasingly being diagnosed in children. [...] These three gluten-related disorders are treated with a gluten-free diet.

- ^ Ferreira SM, de Mello AP, de Caldas Rosa dos Anjos M, Krüger CC, Azoubel PM, de Oliveira Alves MA (January 15, 2016). "Utilization of sorghum, rice, corn flours with potato starch for the preparation of gluten-free pasta". Food Chem. 191: 147–51. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.085. PMID 26258714.

- ^ Padalino L, Mastromatteo M, Lecce L, Spinelli S, Conte A, Del Nobile MA (March 2015). "Optimization and characterization of gluten-free spaghetti enriched with chickpea flour". Int J Food Sci Nutr. 66 (2): 148–58. doi:10.3109/09637486.2014.959897. PMID 25519246. S2CID 21063476.

- ^ Li, Man; Zhu, Ke-Xue; Guo, Xiao-Na; Brijs, Kristof; Zhou, Hui-Ming (July 1, 2014). "Natural Additives in Wheat-Based Pasta and Noodle Products: Opportunities for Enhanced Nutritional and Functional Properties". Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 13 (4): 347–357. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12066. ISSN 1541-4337. PMID 33412715.

- ^ a b c Quessenberry, Sara. "Dried Vs. Fresh Pasta". Real Simple. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Christensen, Emma. "Dry Pasta vs. Fresh Pasta: What's the Difference?". The Kitchn. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ a b Laux, Sandra. "Types of Pasta". Mangia Bene Pasta. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019. Retrieved March 28, 2012.

- ^ Moskin, Julia (April 8, 2024). "Yes, You Can Wash Cast Iron: 5 Big Kitchen Myths, Debunked". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ a b c d Moskin, Julia (April 20, 2024). "No, Your Spaghetti Doesn't Have to Be al Dente: 5 Pasta Myths, Debunked". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- ^ Montany, Gail (June 19, 2011). "Lidia Bastianich on the quintessential Italian meal". The Aspen Business Journal. Archived from the original on January 30, 2012. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ^ Bastianich, Lidia; Tania, Manuali. Lidia Cooks from the Heart of Italy: A Feast of 175 Regional Recipes (1st ed.).

- ^ Bastianich, Lidia; John, Mariani. How Italian Food Conquered the World (1st ed.).

- ^ "Cavatelli pasta with peperoni cruschi (Senise peppers)". the-pasta-project.com. September 25, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2020.

- ^ "How to Make Pasta Dough". allrecipes. Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ "Fresh Pasta". allrecipes. Archived from the original on March 21, 2012. Retrieved March 24, 2012.

- ^ a b Sicignano, Angelo; Di Monaco, Rossella; Masi, Paolo; Cavella, Silvana (2015). "From raw material to dish: Pasta quality step by step". Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture. 95 (13): 2579–2587. Bibcode:2015JSFA...95.2579S. doi:10.1002/jsfa.7176. PMID 25783568.

- ^ a b c d e "The complexities of durum milling". world-grain.com. Sosland Publishing Co. July 2, 2014. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 15, 2016.

- ^ a b Sissons, M (2008). "Role of durum wheat composition on the quality of pasta and bread". Food. 2 (2): 75–90.

- ^ "How pasta is made". made how. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Gao, Yupeng; Janes, Marlene E; Chaiya, Busarawan; Brennan, Margaret A; Brennan, Charles S; Prinyawiwatkul, Witoon (2018). "Gluten-free bakery and pasta products: Prevalence and quality improvement". International Journal of Food Science & Technology. 53 (1): 19–32. doi:10.1111/ijfs.13505. hdl:10182/10123.

- ^ Padalino, Lucia; Conte, Amalia; Del Nobile, Matteo Alessandro (December 9, 2016). "Overview on the General Approaches to Improve Gluten-Free Pasta and Bread". Foods. 5 (4): 87. doi:10.3390/foods5040087. ISSN 2304-8158. PMC 5302439. PMID 28231182.

- ^ Recipe Tips. "Pasta Handling, Safety & Storage". Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ a b Roos, Yrjö H (2010). "Glass Transition Temperature and its Relevance in Food Processing". Annual Review of Food Science and Technology. 1: 469–496. doi:10.1146/annurev.food.102308.124139. PMID 22129345. S2CID 23621696.

- ^ Takhar, Pawan Singh; Kulkarni, Manish V; Huber, Kerry (2006). "Dynamic Viscoelastic Properties of Pasta As a Function of Temperature and Water Content". Journal of Texture Studies. 37 (6): 696–710. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4603.2006.00079.x.

- ^ a b c d Shewry, P. R; Halford, N. G; Belton, P. S; Tatham, A. S (2002). "The structure and properties of gluten: An elastic protein from wheat grain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 357 (1418): 133–142. doi:10.1098/rstb.2001.1024. PMC 1692935. PMID 11911770.

- ^ Kill, R. C.; Turnbull, K (2001). "Pasta and semolina technology".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ De Noni, Ivano; Pagani, Maria A (2010). "Cooking Properties and Heat Damage of Dried Pasta as Influenced by Raw Material Characteristics and Processing Conditions". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 50 (5): 465–472. doi:10.1080/10408390802437154. PMID 20373190. S2CID 12873153.

- ^ a b c d Petitot, Maud; Abecassis, Joël; Micard, Valérie (2009). "Structuring of pasta components during processing: Impact on starch and protein digestibility and allergenicity". Trends in Food Science & Technology. 20 (11–12): 521–532. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2009.06.005.

- ^ "Estimate of world pasta production". Organization of Pasta Manufacturers, United Nations. December 1, 2015. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ a b "The World Pasta Industry in Figures: World pasta production in 2016" (PDF). International Pasta Organization. 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ Daniel Workman (May 27, 2019). "Top Pasta Exporters by Country". World's Top Exports. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Pasta for all. Worldwide sales continue to grow". Food Business. May 29, 2018. Archived from the original on June 12, 2018. Retrieved June 7, 2018.

- ^ United States Food and Drug Administration (2024). "Daily Value on the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels". FDA. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024. Retrieved March 28, 2024.

- ^ National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Committee to Review the Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium (2019). "Chapter 4: Potassium: Dietary Reference Intakes for Adequacy". In Oria, Maria; Harrison, Meghan; Stallings, Virginia A. (eds.). Dietary Reference Intakes for Sodium and Potassium. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US). pp. 120–121. doi:10.17226/25353. ISBN 978-0-309-48834-1. PMID 30844154. Retrieved December 5, 2024.

- ^ Publishing, Harvard Health. "Glycemic index for 60+ foods - Harvard Health". Harvard Health. Retrieved September 11, 2018.

- ^ "Pasta". eNotes. Retrieved March 27, 2012.

- ^ Taylor, Elise (October 12, 2020). "Hawa Hassan Shares the Spicy Somali Pasta Recipe From Her New Cookbook, 'In Bibi's Kitchen'". Vogue. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ "The Ethiopian Meal That Blends Spaghetti and Injera".

- ^ "How Colonialism Brought a New Evolution of Pasta to East Africa". KQED. October 2, 2020. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ^ Explore the world of Canto-Western cuisine. Associated Press via NBC News (8 January 2007). Retrieved on 19 September 2013.

- ^ Kartha, Praerna (November 7, 2012). "Macaroni: Desi Style". food-dee-dum.com. Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ "Arishta - Traditional Armenian Homestyle Pasta". November 5, 2022.

- ^ "Threads of God". Gastro Obscura. Archived from the original on November 21, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2022.

- ^ Tipos de macarrão. Receitas da Fulaninha. receitasdafulaninha.blogspot.com.br. November 2011

- ^ Somma, Marianna (February 20, 2024). "Storia delle Fettuccine Alfredo, il più famoso piatto italo-americano" [The history of Fettuccine Alfredo, the most famous Italian-American dish]. Wine and Food Tour (in Italian). Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ Cesari, Luca (September 24, 2023). "Lo strano caso delle Fettuccine Alfredo, il piatto quasi sconosciuto in Italia e famoso negli Usa" [The strange case of Fettuccine Alfredo, an almost unknown dish in Italy that's famous in America]. Gambero Rosso (in Italian). Retrieved October 20, 2024.

- ^ "What is Boscaiola Sauce? A Deep Dive into Its Heritage and Modern Use". maxandtom.com. August 14, 2024. Retrieved October 19, 2024.

- ^ "Rules for the Review of Legislation on Production of Flour and Pasta". Italian Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Rules for the Review of Legislation on Production of Flour and Pasta (English Translation)" (PDF). Union of Organisations of Manufacturers of Pasta Products to the EU. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 4, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act, Title 21, Chapter 9, S. IV, Sec. 341" (PDF). Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Code of Federal Regulation, Title 21 Part 139". Archived from the original on June 8, 2010. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "State of Connecticut General Provisions, Chapter 417, Sections 21a-28 (Pure Foods and Drugs)". Archived from the original on August 11, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "State of Florida Statutes, Chapter 500.301–500.306 (Food Products)". Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Utah Administrative Codes – Rule R70-620. Enrichment of Flour and Cereal Products". Archived from the original on December 19, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "Oregon Revised Statues § 616.785 Sale of unenriched flours, macaroni or noodle products prohibited". Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ Duffy, Daniel. "Legislative History of Statute Concerning the Regulation of Grain Product". Connecticut General Assembly. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Code of Federal Regulation, Title 7, Part 210 – National School Lunch Program". GPO. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "U.S. Code of Federal Regulation, Title 7, Part 220 – National School Breakfast Program". GPO. Archived from the original on July 7, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ^ "USDA Buying Guide for Child Nutrition Programs – Grains and Bread" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 13, 2013. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

Bibliography

- Serventi, Silvano; Sabban, Françoise (2002). Pasta: the Story of a Universal Food. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0231124422.