Placentation

| Placentation | |

|---|---|

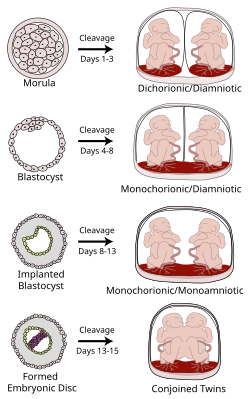

Placentation in the human resulting from cleavage at various gestational ages | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | placentatio |

| MeSH | D010929 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

Placentation is the formation, type and structure, or modes of arrangement of the placenta. The function of placentation is to transfer nutrients, respiratory gases, and water from maternal tissue to a growing embryo, and in some instances to remove waste from the embryo. Placentation is best known in live-bearing mammals (Theria), but also occurs in some fish, reptiles, amphibians, a diversity of invertebrates, and flowering plants. In vertebrates, placentas have evolved more than 100 times independently, with the majority of these instances occurring in squamate reptiles.

The placenta can be defined as an organ formed by the sustained apposition or fusion of fetal membranes and parental tissue for physiological exchange.[1] This definition is modified from the original Mossman (1937)[2] definition, which constrained placentation in animals to only those instances where it occurred in the uterus.

In mammals

[edit]In live bearing mammals, the placenta forms after the embryo implants into the wall of the uterus. The developing fetus is connected to the placenta via an umbilical cord. Mammalian placentas can be classified based on the number of tissues separating the maternal from the fetal blood. These include:

- endotheliochorial placentation

- In this type of placentation, the chorionic villi are in contact with the endothelium of maternal blood vessels. (e.g. in most carnivores like cats and dogs)

- epitheliochorial placentation

- Chorionic villi, growing into the apertures of uterine glands ( epithelium). (e.g. in ruminants, horses, whales, lower primates, dugongs)

- hemochorial placentation

- In hemochorial placentation maternal blood comes in direct contact with the fetal chorion, which it does not in the other two types.[3] It may avail for more efficient transfer of nutrients etc., but is also more challenging for the systems of gestational immune tolerance to avoid rejection of the fetus.[4] (e.g. in higher order primates, including humans, and also in rabbits, guinea pigs, mice, and rats)[5]

During pregnancy, placentation is the formation and growth of the placenta inside the uterus. It occurs after the implantation of the embryo into the uterine wall and involves the remodeling of blood vessels in order to supply the needed amount of blood. In humans, placentation takes place 7–8 days after fertilization.

In humans, the placenta develops in the following manner. Chorionic villi (from the embryo) on the embryonic pole grow, forming chorion frondosum. Villi on the opposite side (abembryonic pole) degenerate and form the chorion laeve (or chorionic laevae), a smooth surface. The endometrium (from the mother) over the chorion frondosum (this part of the endometrium is called the decidua basalis) forms the decidual plate. The decidual plate is tightly attached to the chorion frondosum and goes on to form the actual placenta. Endometrium on the opposite side to the decidua basalis is the decidua parietalis. This fuses with the chorion laevae, thus filling up the uterine cavity.[6]

In the case of twins, dichorionic placentation refers to the presence of two placentas (in all dizygotic and some monozygotic twins). Monochorionic placentation occurs when monozygotic twins develop with only one placenta and bears a higher risk of complications during pregnancy. Abnormal placentation can lead to an early termination of pregnancy, for example in pre-eclampsia.

Source-tissue types

[edit]Placenta can also be divided according to what kind of structure it develops from. There are two vessel-rich features in the amniote, the yolk sac and the allantois. When the chorion fuses with the former, the result is a choriovitelline placenta. When it fuses with the latter, the result is a chorioallantoic placenta. Most mammals first form a temporaty choriovitelline placenta, then the chorioallantoic placenta takes over. (Primates do not form a definite choriovitelline placenta by fusion, but strong expression conservation suggest that the yolk sac remains useful.)[7] Marsupials mostly have choriovitelline placental tissue. Rodents maintain both types throughout gestation.[8][9]

In lizards and snakes

[edit]As placentation often results during the evolution of live birth, the more than 100 origins of live birth in lizards and snakes (Squamata) have seen close to an equal number of independent origins of placentation. This means that the occurrence of placentation in Squamata is more frequent than in all other vertebrates combined,[10] making them ideal for research on the evolution of placentation and viviparity itself. In most squamates, two separate placentae form, utilising separate embryonic tissue (the chorioallantoic and yolk-sac placentae). In species with more complex placentation, we see regional specialisation for gas,[11] amino acid,[12] and lipid transport.[13] Placentae form following implantation into uterine tissue (as seen in mammals) and formation is likely facilitated by a plasma membrane transformation.[14]

Most reptiles exhibit strict epitheliochorial placentation (e.g. Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii) however at least two examples of endotheliochorial placentation have been identified (Mabuya sp. and Trachylepis ivensi).[15] Unlike eutherian mammals, epitheliochorial placentation is not maintained by maternal tissue as embryos do not readily invade tissues outside of the uterus.[16]

Research

[edit]The placenta is an organ that has evolved multiple times independently,[17] evolved relatively recently in some lineages, and exists in intermediate forms in living species; for these reasons it is an outstanding model to study the evolution of complex organs in animals.[1][18] Research into the genetic mechanisms that underpin the evolution of the placenta have been conducted in a diversity of animals including reptiles,[19][20] seahorses,[21] and mammals.[22]

The genetic processes that support the evolution of the placenta can be best understood by separating those that result in the evolution of new structures within the animal and those that result in the evolution of new functions within the placenta.[1]

Evolution of placental structures

[edit]In all placental animals, placentas have evolved through the utilisation of existing tissues.[1] In viviparous mammals and reptiles placentas form from the intimate interaction of the uterus and a series of embryonic membranes including the chorioallantoic and yolk sac membranes. In guppies placental tissues form between the ovarian tissue and the egg membrane. In pipefish placentas form following the interaction with the egg and the skin.

Despite the placenta forming from pre-existing tissues, in many instances new structures can evolve within these pre-existing tissues. For example, in male seahorses the underbelly skin has become highly modified to form a pouch in which embryos can develop. In mammals and some reptiles, including the viviparous southern grass skink, the uterus becomes regionally specialised to support placental functions, within each of these regions being a new specialised uterine structure. In the southern grass skink three distinct regions of the placenta form which likely perform different functions; the placentome supports nutrient transfer via membrane bound transport proteins, the paraplacentome supports the exchange of respiratory gasses, and the yolk sac placenta supports lipid transport via apocrine secretion.[19][23]

Evolution of placental functions

[edit]Placental functions include nutrient transport, gas exchange, maternal-fetal communication, and waste removal from the embryo.[1] These functions have evolved by a series of general processes such as re-purposing processes found in the ancestral tissues from which a placenta is derived, recruiting the expression of genes expressed elsewhere in the organism to perform new functions in placental tissues, and the evolution of new molecular processes following the formation of new placenta specific genes.

In mammals, maternal-fetal communication occurs via the production of a range of signalling molecules and their receptors in the chorioallantoic membrane of the embryo and the endometrium of the mother. Examination of these tissues in egg-laying and other independently evolved live bearing vertebrates has shown us that many of these signalling molecules are expressed widely in vertebrate species and were probably expressed in the ancestral amniote vertebrate.[20] This suggests that maternal fetal communication has evolved by utilising the existing signalling molecules and their receptors, from which placental tissues are derived.

In plants

[edit]In flowering plants, placentation is the attachment of ovules inside the ovary.[24] The ovules inside a flower's ovary (which later become the seeds inside a fruit) are attached via funiculi, the plant part equivalent to an umbilical cord. The part of the ovary where the funiculus attaches is referred to as the placenta.

In botany, the term placentation most commonly refers to the arrangement of ovules inside an ovary. Placentation types include:

- Basal: The placenta is found in mono to multi carpellary, syncarpous ovary. Usually a single ovule is attached at the base (bottom). It is unilocular(Single chamber). E.g.: Helianthus, Tridex, Tagetus.

- Parietal: It is found in bicarpellary to multicarpellary syncarpous ovary. Unilocular ovary becomes bilocular due to formation of false septum.E.g.: Cucumber

- Axile : it is found in bicarpellary to multicarpellary syncarpous ovary. The carpels fuse to form septa forming a central axis and ovules are arranged on the axis. E.g.: Hibiscus, lemon, tomato, lilly.

- Apical: The placenta is at the apex (top) of the ovary. Simple or compound ovary.

- Superficial: Similar to axile, but placentae are on inner surfaces of multilocular ovary (e.g. Nymphaea)

- Free central : It is found in bicarpellary to multicarpellary syncarpous ovary. Due to degradation of false septum unilocular condition is formed and ovules are arranged on the central axis. E.g.: Dianthus, Primula (primroses)

- Marginal : It is found in monocarpellary unilocular ovary, placenta forms a rigid along ventral side and ovules are arranged in two vertical rows. E.g.: Pisum sativum (pea)

-

Basal

-

Parietal

-

Axile

-

Free central

-

Marginal

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Griffith, OW; Wagner, GP (2017). "The placenta as a model for understanding the origin and evolution of vertebrate organs". Nature Ecology and Evolution. 1 (4): 0072. Bibcode:2017NatEE...1...72G. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0072. PMID 28812655. S2CID 32213223.

- ^ Mossman, H. Comparative Morphogenesis of the Fetal Membranes and Accessory Uterine Structures Vol. 26 (Carnegie Institution of Washington, 1937).

- ^ thefreedictionary.com > hemochorial placenta Citing: Dorland's Medical Dictionary for Health Consumers. Copyright 2007 by Saunders

- ^ Elliot, M.; Crespi, B. (2006). "Placental invasiveness mediates the evolution of hybrid inviability in mammals". The American Naturalist. 168 (1): 114–120. doi:10.1086/505162. PMID 16874618. S2CID 16661549.

- ^ Claim for guinea pigs, rabbits, mice, and rats taken from: Thornburg KL, Faber JJ (October 1976). "The steady state concentration gradients of an electron-dense marker (ferritin) in the three-layered hemochorial placenta of the rabbit". J. Clin. Invest. 58 (4): 912–25. doi:10.1172/JCI108544. PMC 333254. PMID 965495.

- ^ T.W. Sadler, Langman's Medical Embryology, 11th edition, Lippincott & Wilkins

- ^ Cindrova-Davies, Tereza; Jauniaux, Eric; Elliot, Michael G.; Gong, Sungsam; Burton, Graham J.; Charnock-Jones, D. Stephen (13 June 2017). "RNA-seq reveals conservation of function among the yolk sacs of human, mouse, and chicken". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (24). doi:10.1073/pnas.1702560114. PMC 5474779.

- ^ Ross, Connor; Boroviak, Thorsten E. (28 July 2020). "Origin and function of the yolk sac in primate embryogenesis". Nature Communications. 11 (1). doi:10.1038/s41467-020-17575-w. PMC 7387521.

- ^ Enders, A.C. (March 2009). "Reasons for Diversity of Placental Structure". Placenta. 30: 15–18. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2008.09.018. PMID 19007983. Retrieved 2 July 2022.

- ^ Blackburn, DG; Flemming, AF (2009). "Morphology, development, and evolution of fetal membranes and placentation in squamate reptiles". J. Exp. Zool. (Mol. Dev. Evol.). 312B (6): 579–589. Bibcode:2009JEZB..312..579B. doi:10.1002/jez.b.21234. PMID 18683170.

- ^ Adams, S. M., Biazik, J. M., Thompson, M. B., & Murphy, C. R. (2005). Cyto‐epitheliochorial placenta of the viviparous lizard Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii: A new placental morphotype. Journal of morphology, 264(3), 264-276.Chicago

- ^ Itonaga, K.; Wapstra, E.; Jones, S. M. (2012). "A novel pattern of placental leucine transfer during mid to late gestation in a highly placentotrophic viviparous lizard". Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution. 318 (4): 308–315. Bibcode:2012JEZB..318..308I. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22446. PMID 22821866.

- ^ Griffith, O. W., Ujvari, B., Belov, K., & Thompson, M. B. (2013). Placental lipoprotein lipase (LPL) gene expression in a placentotrophic lizard, Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii. Journal of Experimental Zoology Part B: Molecular and Developmental Evolution.

- ^ Murphy, C. R.; Hosie, M. J.; Thompson, M. B. (2000). "The plasma membrane transformation facilitates pregnancy in both reptiles and mammals". Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 127 (4): 433–439. doi:10.1016/s1095-6433(00)00274-9. PMID 11154940.

- ^ Blackburn, D. G., & Flemming, A. F. (2010). Reproductive specializations in a viviparous African skink: Implications for evolution and biological conservation.

- ^ Griffith, O. W.; Van Dyke, J. U.; Thompson, M. B. (2013). "No implantation in an extra-uterine pregnancy of a placentotrophic reptile". Placenta. 34 (6): 510–511. doi:10.1016/j.placenta.2013.03.002. PMID 23522396.

- ^ Griffith, OW; Blackburn, DG; Brandley, MC; Van Dyke, JU; Whittington, CW; Thompson, MB (2015). "Ancestral state reconstructions require biological evidence to test evolutionary hypotheses: A case study examining the evolution of reproductive mode in squamate reptiles". J Exp Zool B. 493 (6): 493–503. Bibcode:2015JEZB..324..493G. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22614. PMID 25732809.

- ^ Griffith, Oliver (23 February 2017). "Using the placenta to understand how complex organs evolve". The Conversation. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ^ a b Griffith, OW; Brandley, MC; Belov, K; Thompson, MB (2016). "Reptile pregnancy is underpinned by complex changes in uterine gene expression: a comparative analysis of the uterine transcriptome in viviparous and oviparous lizards". Genome Biol Evol. 8 (10): 3226–3239. doi:10.1093/gbe/evw229. PMC 5174741. PMID 27635053.

- ^ a b Griffith, OW; Brandley, MC; Whittington, CM; Belov, K; Thompson, MB (2016). "Comparative genomics of hormonal signaling in the chorioallantoic membrane of oviparous and viviparous amniotes". Gen Comp Endocrinol. 244: 19–29. doi:10.1016/j.ygcen.2016.04.017. PMID 27102939.

- ^ Whittington, CW; Griffith, OW; Qi, W; Thompson, MB; Wilson, AB (2015). "Seahorse brood pouch transcriptome reveals common genes associated with vertebrate pregnancy". Mol Biol Evol. 32 (12): 3114–3131. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv177. hdl:20.500.11850/110832. PMID 26330546.

- ^ Lynch, V. J.; Nnamani, M. C.; Kapusta, A.; Brayer, K.; Plaza, S. L.; Mazur, E. C.; Graf, A. (2015). "Ancient transposable elements transformed the uterine regulatory landscape and transcriptome during the evolution of mammalian pregnancy". Cell Reports. 10 (4): 551–561. doi:10.1016/j.celrep.2014.12.052. PMC 4447085. PMID 25640180.

- ^ Griffith, OW; Ujvari, B; Belov, K; Thompson, MB (2013). "Placental lipoprotein lipase (LPL) gene expression in a placentotrophic lizard, Pseudemoia entrecasteauxii". J Exp Zool B. 320 (7): 465–470. doi:10.1002/jez.b.22526. PMID 23939756.

- ^ "Flowers" At: Botany Online At: University of Hamburg Department of Biology. (see External links below).

External links

[edit]- Fachbereich Biologie (Department of Biology) → teaching stuff → B-Online → Homepage: Botany Online - The Internet Hypertextbook → Contents → How to Identify Plants → Flowers