Panthera fossilis

| Panthera fossilis Temporal range:

| |

|---|---|

| |

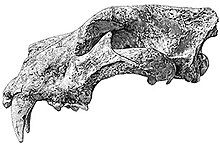

| Skull from Azé, France | |

| |

| Life restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Feliformia |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | †P. fossilis

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Panthera fossilis (Reichenau, 1906)

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Panthera fossilis (also known as Panthera leo fossilis or Panthera spelaea fossilis) is an extinct species of cat belonging to the genus Panthera, known from remains found in Eurasia spanning the Middle Pleistocene and possibly into the Early Pleistocene.

Although often historically considered a subspecies of the living lion (Panthera leo), Panthera fossilis is currently either considered to be ancestral to[1] or a chronosubspecies of Panthera spelaea (commonly known as the cave lion or steppe lion).[2][3] In comparison to Late Pleistocene Panthera spelaea specimens, Panthera fossilis tends to be considerably larger,[2] up to 400–500 kilograms (880–1,100 lb), considerably exceeding modern lions in size, and making them among the largest cats to have ever lived.[4][5]

Discoveries

[edit]It was first described from remains excavated near Mauer in Germany.[6] Bone fragments of P. fossilis were also excavated near Pakefield in the United Kingdom, which are estimated at 680,000 years old.[7] In Poland, remains of P. fossilis have been found at various sites dating to between 750,000 to 240,000 years ago.[8] Bone fragments excavated near Isernia in Italy are estimated at between 600,000 and 620,000 years old.[9] The first Asian record of a fossilis lion was found in the Kuznetsk Basin in western Siberia and dates to the late Early Pleistocene.[10]

Evolution

[edit]P. fossilis is estimated to have evolved in Eurasia about 600,000 years ago from a large pantherine cat that originated in the Tanzanian Olduvai Gorge about 1.2–1.7 million years ago. This cat entered Eurasia about 780,000–700,000 years ago and gave rise to several lion-like forms. The first fossils that can be definitively classified as P. fossilis date to circa 660,000–612,000 years ago.[3] Possibly earlier records of P. fossilis. are known from the late Early Pleistocene (over 780,000 years ago) of Western Siberia.[10] Recent nuclear genomic evidence suggest that interbreeding between modern lions and all Eurasian fossil lions took place up until 500,000 years ago, but by 470,000 years ago, no subsequent interbreeding between the two lineages occurred.[10][11]

The arrival of Panthera (spelaea) fossilis in Europe was part of a faunal turnover event around the Early-Middle Pleistocene transition in which many of the species that characterised the preceeding late Villafranchian became extinct. In the carnivore guild, this notably included the giant hyena Pachycrocuta and the sabertooth cat Megantereon. Following the arrival of Panthera (spelaea) fossilis the lion-sized sabertooth cat Homotherium and the "European jaguar" Panthera gombaszoegensis became much rarer,[12] ultimately becoming extinct in the late Middle Pleistocene, with competition with lions suggested to be a likely important factor.[13][14] Between 300-100,000 years ago, Panthera fossils evolved into the cave lion (Panthera spelaea), marked by a reduction in body size and a number of changes to its skeletal anatomy (with intermediates between the two dubbed Panthera spelaea intermedia).[5]

Description

[edit]

Remains of P. fossilis indicate that it was larger than the modern lion and was among the largest known cats ever, with the largest specimens suggested to have a body length of 2.5–2.9 metres (8.2–9.5 ft), shoulder height of 1.4–1.5 metres (4.6–4.9 ft) and body mass of 400–500 kilograms (880–1,100 lb).[5] Skeletal remains of P. fossilis populations in Siberia measure larger than those in Central Europe.[10][15] Compared to its decendant Panthera spelaea. P. fossilis had a slightly wider muzzle and nasal region of the skull, though the postorbital and mastoid are narrower, the orbits (eye sockets) are smaller, the bullae are less inflated, the canine teeth are more narrow and less flattened, the incisors are smaller, the upper second premolar and upper fourth premolar are narrower, the upper and lower third premolar and lower fourth premolars have smaller cusps.[16] Another notable difference is that the front part of the upper skull surface (the frontal-nasal region) is typically concave, while this is less frequent in Panthera spelaea. The differences between the skulls of P. fossilis and P. spelaea have been described as relatively subtle.[1]

In comparison to the modern lion, in addition to being larger, the upper second premolar of P. fossilis is larger, and the cusp morphology of the upper fourth premolar is different (having a shorter metastyle).[16]

Taxonomic history

[edit]P. fossilis was historically considered an early lion (P. leo) subspecies as Panthera leo fossilis.[9] Some authors considered it a subspecies of Panthera spelaea (Panthera spelaea fossilis) or treat it as a distinct species.[17][18] Some employ a subgenus of Panthera, "Leo", to contain several lion-like members of Panthera, including P. leo, P. spelaea, P. atrox and P. fossilis.[10] A 2022 study concluded that P. fossilis and P. spelaea represented a chronospecies lineage, with most differences between the two species explainable by size differences.[1]

Results of mitochondrial genome sequences derived from two Beringian specimens of Panthera spelaea indicate that it and Panthera fossilis were distinct enough from the modern lion to be considered separate species.[19]

Ecology

[edit]During the Middle Pleistocene, Panthera fossilis was the dominant apex predator in European ecosystems, likely able to displace every other contemporaneous predator species from kills/carcasses.[8]

Herbivores that coexisted with the lion included the hippopotamus, rhinoceroses of the genus Stephanorhinus (such as Merck's rhinoceros and the narrow-nosed rhinoceros), straight-tusked elephant, moose, steppe bison, red deer, roe deer and fallow deer. Sympatric predators included brown bears, wolves, cave hyenas, the large sabertooth cat Homotherium, European leopards, and the "European jaguar" Panthera gombaszoegensis.[20][10][15][14][21][22]

Relationship with humans

[edit]The only evidence of human interaction with Panthera fossilis is from Gran Dolina, Spain, dating to Marine Isotope Stage 9 (~300,000 years ago), where a specimen of Panthera fossilis displays cut marks thought to be produced archaic humans, who are suggested to have butchered the animal for its flesh.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Sabo, Martin; Tomašových, Adam; Gullár, Juraj (August 2022). "Geographic and temporal variability in Pleistocene lion-like felids: Implications for their evolution and taxonomy". Palaeontologia Electronica. 25 (2): 1–27. doi:10.26879/1175. ISSN 1094-8074. S2CID 251855356.

- ^ a b Marciszak, Adrian; Ivanoff, Dmitry V.; Semenov, Yuriy A.; Talamo, Sahra; Ridush, Bogdan; Stupak, Alina; Yanish, Yevheniia; Kovalchuk, Oleksandr (March 2023). "The Quaternary lions of Ukraine and a trend of decreasing size in Panthera spelaea". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. 30 (1): 109–135. doi:10.1007/s10914-022-09635-3. ISSN 1064-7554.

- ^ a b Iannucci, A.; Mecozzi, B.; Pineda, A.; Raffaele, S.; Carpentieri, M.; Rabinovich, R.; Moncel, M.-H. (2024-06-24). "Early occurrence of lion (Panthera spelaea) at the Middle Pleistocene Acheulean site of Notarchirico (MIS 16, Italy)". Quaternary Science. 39 (5): 683–690. Bibcode:2024JQS....39..683I. doi:10.1002/jqs.3639. ISSN 0267-8179.

- ^ Persico, Davide (June 2021). "First fossil record of cave lion (Panthera (Leo) spelaea intermedia) from alluvial deposits of the Po River in northern Italy". Quaternary International. 586: 14–23. Bibcode:2021QuInt.586...14P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2021.02.029.

- ^ a b c Marciszak, Adrian; Gornig, Wiktoria (September 2024). "From giant to dwarf: A trend of decreasing size in Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) and its likely implications". Earth History and Biodiversity. 1: 100007. doi:10.1016/j.hisbio.2024.100007.

- ^ Reichenau, W. V. (1906). "Beiträge zur näheren Kenntnis der Carnivoren aus den Sanden von Mauer und Mosbach". Abhandlungen der Großherzoglichen Hessischen Geologischen Landesanstalt zu Darmstadt. 4 (2): 125.

- ^ Lewis, M.; Pacher, M.; Turner, A. (2010). "The larger Carnivora of the West Runton Freshwater Bed". Quaternary International. 228 (1–2): 116–135. Bibcode:2010QuInt.228..116L. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2010.06.022.

- ^ a b Marciszak, Adrian; Lipecki, Grzegorz; Pawłowska, Kamilla; Jakubowski, Gwidon; Ratajczak-Skrzatek, Urszula; Zarzecka-Szubińska, Katarzyna; Nadachowski, Adam (20 December 2021). "The Pleistocene lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) from Poland – A review". Quaternary International. 605–606: 213–240. Bibcode:2021QuInt.605..213M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2020.12.018. Retrieved 22 March 2024 – via Elsevier Science Direct.

- ^ a b Sala, B. (1990). "Panthera leo fossilis (v. Reichenau, 1906) (Felidae) de Iserna la Pineta (Pléistocene moyen inférieur d'Italie)". Géobios. 23 (2): 189–194. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(06)80051-3.

- ^ a b c d e f Sotnikova, M.V. & Foronova, I.V. (2014). "First Asian record of Panthera (Leo) fossilis (Mammalia, Carnivora, Felidae) in the Early Pleistocene of Western Siberia, Russia". Integrative Zoology. 9 (4): 517–530. doi:10.1111/1749-4877.12082. PMID 24382145.

- ^ Manuel, M. d.; Ross, B.; Sandoval-Velasco, M.; Yamaguchi, N.; Vieira, F. G.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Liu, S.; Martin, M. D.; Sinding, M.-H. S.; Mak, S. S. T.; Carøe, C.; Liu, S.; Guo, C.; Zheng, J.; Zazula, G.; Baryshnikov, G.; Eizirik, E.; Koepfli, K.-P.; Johnson, W. E.; Antunes, A.; Sicheritz-Ponten, T.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Larson, G.; Yang, H.; O’Brien, S. J.; Hansen, A. J.; Zhang, G.; Marques-Bonet, T.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2020). "The evolutionary history of extinct and living lions". PNAS. 117 (20): 10927–10934. Bibcode:2020PNAS..11710927D. doi:10.1073/pnas.1919423117. PMC 7245068. PMID 32366643.

- ^ Madurell-Malapeira, Joan; Prat-Vericat, Maria; Bartolini-Lucenti, Saverio; Faggi, Andrea; Fidalgo, Darío; Marciszak, Adrian; Rook, Lorenzo (September 2024). "A Review on the Latest Early Pleistocene Carnivoran Guild from the Vallparadís Section (NE Iberia)". Quaternary. 7 (3): 40. Bibcode:2024Quat....7...40M. doi:10.3390/quat7030040. ISSN 2571-550X.

- ^ Anton, M; Galobart, A; Turner, A (May 2005). "Co-existence of scimitar-toothed cats, lions and hominins in the European Pleistocene. Implications of the post-cranial anatomy of (Owen) for comparative palaeoecology". Quaternary Science Reviews. 24 (10–11): 1287–1301. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2004.09.008.

- ^ a b Marciszak, Adrian; Lipecki, Grzegorz (September 2022). "Panthera gombaszoegensis (Kretzoi, 1938) from Poland in the scope of the species evolution". Quaternary International. 633: 36–51. Bibcode:2022QuInt.633...36M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2021.07.002.

- ^ a b Burger, J.; Rosendahl, W.; Loreille, O.; Hemmer, H.; Eriksson, T.; Götherström, A.; Hiller, J.; Collins, M. J.; Wess, T. & Alt, K. W. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 30 (3): 841–849. Bibcode:2004MolPE..30..841B. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. PMID 15012963.

- ^ a b Sabol, M. (2014). "Panthera fossilis (Reichenau, 1906) (Felidae, Carnivora) from Za Hájovnou Cave (Moravia, The Czech Republic): A Fossil Record from 1987-2007". Acta Musei Nationalis Pragae, Series B, Historia Naturalis. 70 (1–2): 59–70. doi:10.14446/AMNP.2014.59.

- ^ Marciszak, A.; Stefaniak, K. (2010). "Two forms of cave lion: Middle Pleistocene Panthera spelaea fossilis Reichenau, 1906 and Upper Pleistocene Panthera spelaea spelaea Goldfuss, 1810 from the Bísnik Cave, Poland". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 258 (3): 339–351. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2010/0117.

- ^ Marciszak, A.; Schouwenburg, C.; Darga, R. (2014). "Decreasing size process in the cave (Pleistocene) lion Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810) evolution – A review". Quaternary International. Fossil remains in karst and their role in reconstructing Quaternary paleoclimate and paleoenvironments. 339–340: 245–257. Bibcode:2014QuInt.339..245M. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2013.10.008.

- ^ Barnett, R.; Mendoza, M. L. Z.; Soares, A. E. R.; Ho, S. Y. W.; Zazula, G.; Yamaguchi, N.; Shapiro, B.; Kirillova, I. V.; Larson, G.; Gilbert, M. T. P. (2016). "Mitogenomics of the extinct Cave Lion, Panthera spelaea (Goldfuss, 1810), resolve its position within the Panthera cats". Open Quaternary. 2: 4. doi:10.5334/oq.24. hdl:10576/22920.

- ^ Jackson, D. (2010). "Introduction". Lion. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 1–21. ISBN 978-1861897350.

- ^ Sardella, Raffaele (2014). "Co-occurrence of a sabertoothed cat (Homotherium sp.) with a large lion-like cat (Panthera sp.) in the Middle Pleistocene karst infill from nuova «Cava Zanola» (Paitone, Brescia, Lombardy, Northern Italy)". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana (2). doi:10.4435/BSPI.2014.08 (inactive 2024-11-20). ISSN 0375-7633.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Álvarez-Lao, Diego J. (April 2016). "Middle Pleistocene large-mammal faunas from North Iberia: palaeobiogeographical and palaeoecological implications". Boreas. 45 (2): 191–206. Bibcode:2016Borea..45..191A. doi:10.1111/bor.12148. ISSN 0300-9483.

- ^ Blasco, Ruth; Rosell, Jordi; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Bermúdez de Castro, José M.; Carbonell, Eudald (August 2010). "The hunted hunter: the capture of a lion (Panthera leo fossilis) at the Gran Dolina site, Sierra de Atapuerca, Spain". Journal of Archaeological Science. 37 (8): 2051–2060. Bibcode:2010JArSc..37.2051B. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2010.03.010.