Suntukan

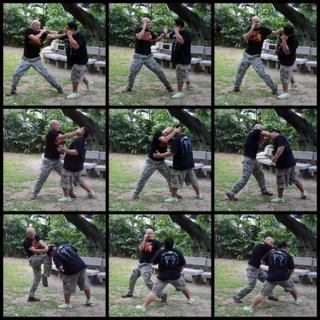

Suntukan with locks, trips, knees, throws and elbows | |

| Also known as | Pangamot, Filipino Boxing, Filipino Dirty Boxing, Mano-mano, Tumbukan, Dirty Boxing, Kali Empty Hand. Foreign terms: Panantukan, Panununtukan. |

|---|---|

| Focus | Depends, but mostly striking, trapping, and grappling |

| Country of origin | |

| Creator | Unknown |

| Famous practitioners | Eduard Folayang, Gabriel "Flash" Elorde, Francisco "Pancho Villa" Guilledo, Ceferino Garcia, Estaneslao "Tanny" del Campo, Buenaventura "Kid Bentura" Lucaylucay, Dan Inosanto, Anderson Silva |

| Parenthood | Originally Arnis but in modern times, may include boxing, judo and jujutsu |

| Ancestor arts | Arnis |

| Descendant arts | Yaw-Yan |

| Related arts | Arnis |

| Olympic sport | No |

Suntukan is the fist-related striking component of Filipino martial arts. In the central Philippine island region of Visayas, it is known as Pangamot or Pakamot and Sumbagay. It is also known as Mano-mano and often referred to in Western martial arts circles of Inosanto lineage as Panantukan. Although it is also called Filipino Boxing, this article pertains to the Filipino martial art and should not be confused with the Western sport of boxing as practiced in the Philippines.

Etymology

[edit]The term suntukan comes from the Tagalog word for punch, suntok. It is the general Filipino term for a fistfight, brawl, or boxing regardless whether the involved had background in martial arts or not as in "suntukan sa Ace hardware" ("brawl at Ace hardware"). The Visayan terms (also found in Waray and Hiligaynon entries)[1][2] pangamot and pakamot come from the word for hand, "kamót", the word pangamot is also used to refer to anything done by hand, making it a rough translation for doing things manually.[3] Due to Cebuano language pronunciation quirks, they are also pronounced natively as pangamut and pakamut, thus the variation of spelling across literature. The Cebuano, Hiligaynon, and Waray Visayan word (or at least sometimes referred to) for "punching" is sumbag,[3][1][2] though the word suntok[1][3], is also listed as a Visayan entry, (in Hiligaynon it is listed as "to thrust").[2] Therefore the word sumbagay in the Visayan languages is a term to refer to any kind of fistfight or brawl.

Mano-mano comes from the Spanish word for "hand", mano, and can translate to "two hands" or "hand-to-hand". The phrase "Mano-mano na lang, o?" ("Why don't we settle this with fists?") is often used to end arguments when tempers have flared in Philippine male society. Filipino Boxing is a contemporary westernized term used by a few instructors to describe suntukan.[4]

Panantukan (often erroneously referred to as panantuken by USA practitioners due to the way Americans pronounce the letters U and A) is a contraction of the Tagalog term pananantukan, according to Dan Inosanto.[5] It is generally attributed to the empty hands and boxing system infused by FMA pioneers Juan "Johnny" Lacoste, Leodoro "Lucky" Lucaylucay and Floro Villabrille[6] into the Filipino martial arts component of the Inosanto Academy and Jeet Kune Do fighting systems developed in the West Coast of the United States. Pananantukan, which Inosanto picked up from his Visayan elder instructors, is a corruption of panununtukan. While the Tagalog of his instructors was not perfect (Lacoste was Waray and the Filipino language based on Tagalog was relatively new when they migrated to the United States), they were highly versed in Filipino martial arts. It is said that originally, Lucaylucay wanted to call his art Suntukan, but he was concerned that it would be confused with Shotokan Karate, so he used the term Panantukan instead.[7][8][9][10]

History

[edit]The main source of this section is taken from a book written by Krishna Godhania entitled: Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art. It is possible that prior to colonization there was an existing unarmed fighting system which was most likely an indigenous form of wrestling though it is arguable whether it was a martial art or not because it was not systemized or formalized. According to the author, Doce Pares grandmaster Eulogio Cañete said that a certain book entitled De los Delitos ("For the Criminals") which was said to be published in 1800 and written by a certain Don Baltazar Gonzales, made or contained references to an empty hand fighting system. Another instructor, Abner Pasa, then said that the copy of the book that Cañete saw was destroyed during World War II and is now lost. However, so far there are no entries in Spanish dictionaries from the 17th to the 19th centuries listing a name for a kind of unarmed fighting as either a sport or a separate fighting system, nor did the chroniclers mention or record anything about a codified system of combat, both armed and unarmed, as well as their training methods. It is also worth mentioning that as early as the 1930s there are already many Filipinos who had background in Japanese martial arts like judo and jujutsu.[11][12] The author then postulates that the origin of suntukan as a martial art today is said to be traceable to the introduction of Western Boxing in the country, which was already a codified sport. When boxing became a popular sport in the 20th century in the Philippines, Filipinos incorporated mainly knife-fighting techniques (some base their movements on double stick) with Western Boxing and some elements of Japanese martial arts that made suntukan a martial art rather than just being a give-all brawl[11].

This is different from the unarmed martial art traditionally practiced in the Southern Philippines as it is more influenced by Malays and Chinese and often do not teach Luzon and Visayan martial artists their own style of fighting for political reasons, thus their martial art cannot be considered as a "Filipino" martial art, just as their culture cannot be considered "Filipino" lest a controversy will spark.[13]

Characteristics

[edit]Striking

[edit]"Filipinos had their own sort of boxing, a bare-handed martial art known as Suntukan. The combatants held their hands high and kept their distance, occasionally charging forward to throw chopping punches, most of which would be fouls not tolerated in American rings."

Suntukan is not a sport, but rather a street-oriented fighting system. The techniques have not been adapted for safety or conformance to a set of rules for competition, thus it has a reputation as "dirty street fighting". It mainly consists of upper-body striking techniques such as punches, elbows, headbutts, shoulder strikes and limb destruction. It is often used in combination with Sikaran, the kicking aspect of Filipino fighting which includes low-line kicks, tripping and knee strikes to the legs, shins, and groin. Many of its other unique movesets include elbow blocks, hand strikes resembling Eskrima movements and other chopping strikes, evasive maneuvers, and parrying stances.[14][4]

Suntukan practitioners typically use triangular footwork to avoid getting hit and look for openings, just like with knife fighting. According to Filipino martial artist Lucky Lucaylucay: "...if your practice is based on knife fighting, you have to become much more sophisticated with your footwork, evasions and delivery because one wrong move could mean death... ...Filipino boxing is exactly like knife fighting, except instead of cutting with a blade, we strike with a closed fist."[14][15]

Grappling

[edit]

Suntukan also consists of limb trapping and immobilization,[4] including the technique called gunting (scissors) because of the scissor-like motions used to stop an opponent's limb from one side while attacking from the other side. Suntukan focuses on countering an opponent's strike with techniques that will nullify further attack by hitting certain bones and other areas to cause damage of the attacking limb. Common limb destructions include guiding incoming straight punches into the defending fighter's elbow (siko) to shatter the knuckles.[16]

Dumog or Filipino wrestling is also an essential component of Suntukan.[17] This type of wrestling is based on the concept of “control points” or “choke points” on the human body, which are manipulated – for example: by grabbing, pushing, pulling - in order to disrupt the opponent’s balance and to keep him off balance. This also creates opportunities for close quarter striking using head butts, knees, forearms and elbows. This is accomplished by the use of arm wrenching, shoving, shoulder ramming, and other off-balancing techniques in conjunction with punches and kicks. For example, the attacker's arm could be grabbed and pulled downward to expose their head to a knee strike.

Weaponry

[edit]Even though suntukan is designed to allow an unarmed practitioner to engage in both armed and unarmed confrontations, it easily integrates the use of weapons such as knives, palmsticks (dulo y dulo) and ice picks.[18][19] These weapons can render suntukan's techniques fatal but do not fundamentally change how the techniques are executed. Weapons in suntukan tend to be small, easily concealed and unobtrusive. Thus, suntukan minimizes contact with the opponent because it is not always known whether an opponent is armed, and knives are very often used in fights and brawls in the Philippines.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] As such, parries and deflections are preferred over blocks and prolonged grappling.

Suntukan is a key component of Arnis and is generally believed to have evolved from the latter.[14] It is theorized to have evolved from Filipino weapons fighting because in warfare, unarmed fighting is usually a method of last resort for when combatants are too close in proximity (such as trapping and grappling range) or have lost their weapons. Aside from this, some unarmed techniques and movements in certain Eskrima systems are directly derived from their own weapon-based forms. In some classical Eskrima systems, the terms Arnis de Mano, De Cadena (Spanish for "of chain") and Cadena de Mano (Spanish for "hand chain") are the names for their empty hand components. Aside from punching, the suntukan components in Eskrima includes kicking, locking, throwing and dumog (grappling).

Usage in sports

[edit]A number of Filipino boxing champions have practiced eskrima and suntukan.[27] While many Filipino boxing champions such as Estaneslao "Tanny" del Campo[28][29] and Buenaventura "Kid Bentura" Lucaylucay[6][30] (Lucky Lucaylucay's father) practiced Olympic and sport boxing, they also used pangamot dirty street boxing which is distinct from western boxing.[31][32]

World champion Ceferino Garcia (regarded as having introduced the bolo punch to the Western world of boxing) wielded a bolo knife in his youth and developed his signature punch from his experience in cutting sugarcane in farm fields with the bladed implement.[27][33] He himself honed his suntukan in the streets, becoming a known unbeatable street fighter due to his skills.[34] Legendary world champion Gabriel "Flash" Elorde studied Balintawak Eskrima (under founder Venancio "Anciong" Bacon)[35] and got his innovative, intricate footwork[36] from his father, "Tatang" Elorde who was the Eskrima champion of Cebu.[15][35] Elorde's style was said to have been adopted by many boxers, including his friend Muhammad Ali.[15][37][35]

Famous and influential suntukan practitioners in boxing and mixed martial arts include:

- Ceferino Garcia

- Gabriel Elorde

- Onassis Parungao - First Filipino fighter in the UFC who studied Arnis de Mano[38]

- Eduard Folayang[4]

- Anderson Silva[4]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Waray Dictionary". dictionary.corporaproject.org. Retrieved 2024-05-13.

- ^ a b c Motus, Cecile (1971). Hiligaynon Dictionary. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 56, 239–240.

- ^ a b c Wolff, John U. (2012-06-24). A Dictionary of Cebuano Visayan.

- ^ a b c d e Almond, John (11 December 2020). "Panantukan: Filipino Boxing". Gonevis. December 11, 2020

- ^ Interview with Dan Inosanto by Daniel Sullivan

- ^ a b Charlson, Steve (October 1996). "His Final Interview". Tedlucaylucay.com. Inside Kung Fu. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ^ "Panantukan Book Review". Bladeforums.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "filipino boxing???". MartialTalk.Com - Friendly Martial Arts Forum Community. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Makephpbb.com". Makephpbb.com. Archived from the original on 18 April 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Filipino Boxing..." defend.net. Archived from the original on April 18, 2014.

- ^ a b Godhania, Krishna (2010). Eskrima: Filipino Martial Art. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2HR: The Crowood Press. pp. 17, 168–175. ISBN 978-1-84797-469-3.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ Estanislao, Noel C. "Judo in the Philippines" (PDF). Filipino Martial Arts Digest – via USADojo.

In the middle and late 30's some Japanese businessmen in the Philippines introduced judo among the youth and students.

- ^ Gutoc-Tomawis, Samira. "The Politics of Labelling Philippine Muslims" (PDF). Arellano Law and Policy Review. 6 (1): 14 – via afrellanolaw.edu.

Many Moros currently define themselves as non-Filipinos according to a 1993 study which showed that 61% of a Muslim sample did not themselves as Filipino citizens.

- ^ a b c d Stradley, Don. "A look at the history of boxing in the Philippines". ESPN. June 25, 2008

- ^ a b c Tovak Kali International. "Filipino Martial Arts - Filipino Kali - Kali Instructor - RBSD - Melbourne - Adelaide". Tovakkali.blogspot.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Filipino Combat Knife Fighting. Youtube.com. 11 June 2007. Retrieved 28 January 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ THE MARTIAL ARTS OF THE PHILIPPINES

- ^ "AGAWAN O HOLDAP?". abante.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2013. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ Calderon, Rossel. "Kinambalan dark ice pick". Abante-tonite.com. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Ex-boxer na hindi kaya sa suntukan, pinatay sa saksak". philstar.com. February 19, 2001. Archived from the original on January 19, 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Calvento, Tony (February 6, 2009). "Grinipuhan, tinarakan sa leeg..." philstar.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Cantos, Joy. "Tinalo sa suntukan, rumesbak ng saksak". philstar.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ "Ungos sa suntukan, nadale sa saksakan". Remate.ph. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Madan, Alvin. "PANALO SA SUNTUKAN, GRINIPUHAN!". abante.com. Archived from the original on September 8, 2011. Retrieved February 4, 2016.

- ^ "Kuya grinipuhan ng bunsong kapatid, tigbak". Remate.ph. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Santamaria, Carlos (November 26, 2012). "'Male pride' led to fatal stabbing of American in Makati". Rappler. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ a b Corky Pasquil (1994). "Documentary: The Great Pinoy Boxing Era". Youtube.com. Retrieved 2016-01-28.

- ^ Godhania, Krishna. "Tanny Del Campo". Warriorseskrima.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2017. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Nathanielsz, Ronnie (January 2, 2008). "Remembering Filipino Great "Flash" Elorde". Boxingscene.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Perry Gil S. Mallari (October 20, 2010). "Characteristics of Filipino Boxing". Filipino Martial Arts Pulse: Kali, Eskrima, Arnis. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Godhania, Krishna. "Western & Filipino Boxing". Krishnagodhania.org. Archived from the original on 17 July 2006. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ FILIPINO STREET BOXING WITH PETER "TISOY" SESCON JR. - PRACTICAL BOXING. Youtube.com. 28 March 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ "We should focus on boxing - The Manila Times Online". Manilatimes.net. July 13, 2013. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Rolando O. Borrinaga (November 27, 1994). "Where Is Ceferino Garcia?". Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ^ a b c "Print Page - Filipino Martial Arts and Boxing". Dogbrothers.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Carlos Ortiz vs. Flash Elorde II (part 1 of 4). Youtube.com. 14 March 2012. Retrieved 28 January 2016 – via YouTube.

- ^ Nathanielsz, Ronnie (March 25, 2012). "Remembering 'Flash' Elorde". Philboxing.com. Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- ^ Almond, John. "Pinoy combat-sports pioneer Onassis Parungao recalls MMA's early days". ABS-CBN. July 1, 2020

Further reading

[edit]- A Guide to Panantukan, the Filipino Boxing Art, Rick Faye, Cambridge Academy Publishing, 2000

External links

[edit]- The Great Pinoy Boxing Era, 1994 documentary on early 1900s Filipino boxing by Corky Pasquil

- Filipino Martial Arts: From Kali and Escrima to Boxing talk at the Smithsonian Museum with Dan Inosanto, Rosie Abriam, Linda España-Maram, Gem Daus