Pakpattan

This article may require cleanup to meet Wikipedia's quality standards. The specific problem is: Images are all over the place, and should be collected into a gallery. (November 2024) |

Pakpattan Sharif

پاکپتّن شریف | |

|---|---|

The highly-revered Shrine of Baba Farid is located in Pakpattan | |

| Coordinates: 30°20′39″N 73°23′2″E / 30.34417°N 73.38389°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | |

| District | Pakpattan |

| Old Name | Ajodhan |

| Elevation | 156 m (512 ft) |

| Population | |

• City | 176,693 |

| • Rank | 48th, Pakistan |

| Demonym | Pakpattni |

| Time zone | UTC+5 (PST) |

| Postal code | 57400 |

| Dialling code | 0457[2] |

Pakpattan (Punjabi and Urdu: پاکپتّن), often referred to as Pākpattan Sharīf ( پاکپتّن شریف; "Noble Pakpattan"), is an ancient, historic city in the Pakistani province of Punjab, serving as the headquarters of the eponymous Pakpattan district. It is among the oldest cities in Asia and ranks as the 48th largest city in Pakistan by population, according to the 2017 census. Pakpattan is the seat of the Sufi Chisti order in Pakistan,[3] and a major pilgrimage destination on account of the Shrine of Baba Farid, a renowned Punjabi poet and Sufi saint. The annual urs fair in his honour draws an estimated 2 million visitors to the town.[4] Over its long history, Pakpattan has endured numerous attacks, followed by cycles of destruction and reconstruction, reflecting its resilience and historical significance.

Etymology

[edit]Pakpattan was originally known as Ajodhan (Hindi: अजोधन) until the 16th century.[5] Ajodhan may be a Sanskrit term that can be interpreted as "eternal wealth" or "eternal prosperity," with Aja meaning "unborn" or "eternal" and Dhana meaning "wealth" or "prosperity." This concept reflects the area's historical and cultural significance, particularly during the medieval period when it served as a prominent center of trade and spiritual learning. It is believed that the name of the city has changed over time, and anecdotally, it may have been known by various names prior to being called Ajodhan.

Pakpattan derives its current name from the combination of two Punjabi words: Pak, meaning "pure," and Pattan, meaning "dock"; this name references a ferry service across the Sutlej River, frequented by pilgrims visiting the Shrine of Baba Farid.[6] The ferry symbolized a metaphorical journey of salvation, with the saint’s spirit guiding believers across the river.[6]

During the Delhi Sultanate and Mughal eras, including the reigns of Akbar and Aurangzeb, the city continued to be known as Ajodhan. However, as the shrine of Baba Farid grew in significance, the name "Pakpattan" gained popular use. Akbar’s Ain-i-Akbari mentions the region, indicating that both names—Ajodhan and Pakpattan—were likely used interchangeably in local and administrative records.[7] Over time, the reverence for Baba Farid's legacy led to "Pakpattan" gradually eclipsing the older name, Ajodhan.

Geography

[edit]Pakpattan is located about 205 km from Multan.[8] Pakpattan is located roughly 40 kilometres (25 mi) from the border with India, and 184 kilometres (114 mi) by road southwest of Lahore.[9] The district is bounded to the northwest by Sahiwal District, to the north by Okara District, to the southeast by the Sutlej River and Bahawalnagar District, and to the southwest by Vehari District.

History

[edit]Ancient

[edit]Pakpattan, located in the fertile plains of Punjab, Pakistan, is believed to have roots that trace back to the Sarasvati-Indus Valley Civilization (est. >7000–1900 BCE), one of the world's oldest urban cultures, located in the Northern area of the Indian subcontinent. Although Pakpattan is widely recognized for its medieval history, its geographical proximity to Harappa, a major center of the Sarasvati-Indus Valley Civilization, suggests that the area may have been part of this ancient network of settlements. Harappa, situated approximately 40 kilometers from Pakpattan, has yielded extensive archaeological evidence of a highly developed urban society characterized by advanced trade, agriculture, and infrastructure.[10]

The Sutlej River, which flows near Pakpattan, played a significant role as a waterway for early civilizations, further supporting the likelihood of human habitation in the region during the Sarasvati-Indus Valley period.[11] [12] While no specific remains of this civilization have been discovered in Pakpattan itself, its location and environmental advantages suggest that it was likely connected to the broader cultural and economic networks of the time. This potential link adds depth to Pakpattan's ancient heritage, emphasizing its historical significance beyond its later medieval prominence.[13]

During the Vedic period (est. >6000-500 BCE), the region now known as Pakpattan was part of the Sapta Sindhu, the "Land of Seven Rivers," prominently mentioned in the Rigveda as the cradle of early Indo-Aryan civilization.[14] The area was traversed by the Sutlej River, known in Vedic times as the Shatudri ("Hundred Streams"), one of the sacred rivers of the Sapta Sindhu region.[15] This era saw the composition of the Vedas and the establishment of a society centered on pastoralism and agriculture.[16] The region was inhabited by tribes mentioned in the Rigveda, such as the Purus, Druhyus, Anus, Turvasas, and Yadus, who engaged in intertribal conflicts and alliances that shaped the cultural and political landscape.[17] Vedic society in the area was patriarchal and organized into clans led by tribal chiefs (Rajans).[18] Religious practices focused on rituals and the worship of natural forces and deities such as Indra, Agni, and Varuna.[19] The Sutlej River played a vital role in sustaining the inhabitants and influencing the region's spiritual and cultural significance in early Vedic civilization.[20]

Pakpattan, originally known by its Hindu name Ajodhan (Hindi: अजोधन), was founded as a village and has a deep-rooted Hindu history that predates its prominence as a Sufi center.[21] [22] Ajodhan was the location of a ferry service across the Sutlej River, which rendered it an important part of the ancient trade routes connecting Multan to Delhi.[5] [23] As an ancient settlement in the Punjab region, Ajodhan was historically significant in Hindu culture and served as a place of trade, pilgrimage, and cultural exchange.[23] Hindu temples and shrines once marked the landscape, catering to the religious practices and rituals of local communities.[22] The town was part of a broader network of settlements along these trade routes in northern India, which allowed Hindu traditions to flourish alongside the development of diverse communities.[23]

With the advent of Islamic rule and the influence of Sufi saints, particularly Baba Farid in the 12th century, Ajodhan (Pakpattan) would eventually become a center of Islamic spirituality, overshadowing its Hindu roots.[24] Nevertheless, the legacy of Hinduism would remain embedded in local folklore and traditions, blending with the area's Sufi heritage to reflect Pakpattan’s rich, layered history.[25]

Medieval

[edit]10th–11th Century

[edit]Given its position on the flat plains of Punjab, Ajodhan (Pakpattan) was vulnerable to waves of foreign invasions from the Middle East and Central Asia that began in the late 8th century.[5] It was captured by Sebüktegin in 977–78 CE and by Mahmud Ghaznavi in 1029–30.[26]

12th–13th Century

[edit]Turkic settlers from Central Asia also arrived in the region from as a result of persecution from the expanding Mongol Empire,[5] and so Ajodhan already had a mosque and Muslim community by the time of the arrival of Baba Farid,[5] who migrated to the town from his native village of Kothewal near Multan around 1195. Despite his presence, Ajodhan remained a small town until after his death,[27] although it was prosperous given its position on trade routes.[28]

Baba Farid's establishment of a Jamia Khana, or convent, in the town where his devotees would gather for religious instruction is seen as a process of the region's shift away from a Hindu orientation to a Muslim one.[5] Large masses of the town's citizenry were noted to gather at the shrine daily in hopes of securing written blessings and amulets from the convent.[5]

Upon Baba Farid's death in 1265, a shrine was constructed that eventually contained a mosque, langar, and several other related buildings.[5] The shrine was among the first Islamic holy sites in South Asia.[5] The shrine later served to elevate the town as a centre of pilgrimage within the wider Islamic world.[29] In keeping with Sufi tradition in Punjab, the shrine maintains influence over smaller shrines throughout the region around Pakpattan that are dedicated to specific events in Baba Farid's life.[30] These secondary shrines form a wilayat, or a "spiritual territory" of the Pakpattan shrine.[30]

14th Century

[edit]Role of the Tughlaq Dynasty

[edit]During the Tughlaq dynasty's reign (1320–1413), Ajodhan (Pakpattan), gained prominence due to its association with the revered Sufi saint Baba Farid. Ghiyath al-Din Tughluq, the dynasty's founder, frequently visited Baba Farid's shrine, reflecting the site's spiritual significance.[31] His son, Muhammad bin Tughluq, also maintained a close relationship with the shrine, commissioning the construction of a grand mausoleum for Baba Farid's successor, Sheikh Alauddin Mauj Darya, which became a notable example of Tughlaq architecture.[32] Following Sheikh Alauddin's passing in 1335, this tomb solidified the site's historical and spiritual importance. This patronage not only enhanced the shrine's status but also elevated the city's importance as a center of Sufism during the Tughlaq era.[32]

In addition to constructing the mausoleum, the Tughlaq rulers, including Muhammad bin Tughluq and his successor Firuz Shah Tughlaq, undertook repairs and enhancements at the Shrine of Baba Farid.[33] They granted ceremonial robes to honor Baba Farid's descendants and fostered a strong association between the Tughlaq court and the shrine.[33] This patronage not only elevated the shrine's status but also reinforced Pakpattan's role as a key center of Sufism during the Tughlaq era.

Ibn Battuta's travels to Ajodhan

The renowned 14th century Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta visited the town in 1334 during his travels through the Indian subcontinent, and paid obeisance at the Baba Farid shrine.[5] In his travel accounts, Battuta described Ajodhan (Pakpattan) as a prominent center of Sufism, emphasizing the local population's deep reverence for the teachings of Baba Farid, who had passed away several decades prior to his visit.[34] Ibn Battuta was notably moved by the spiritual ambiance of the town and observed the devotion with which people visited Baba Farid's shrine, which was already established as a major pilgrimage destination at the time.[35] His accounts provide valuable insight into the medieval importance of Pakpattan as a spiritual and cultural center in the region.[36] Battuta also mentioned witnessing the practice of sati in Ajodhan (Pakpattan), describing the ritual where a widow immolated herself on her deceased husband's funeral pyre as a custom of honor among some locals.[37] [38]

Further conquests and Timur's entry

In 1394, Shaikha Khokhar, a chieftain of the Khokhar tribe and former governor of Lahore under Sultan Mahmud Tughlaq, led a siege on Ajodhan (Pakpattan).[39] [40] This occurred during a period of political instability following the decline of the Tughlaq dynasty, as Shaikha sought to expand his influence across Punjab.[40]

In the late 14th century, the Central Asian conqueror Timur (also known as Tamerlane) launched a campaign through the Indian subcontinent, capturing and often devastating cities along his path. Historical accounts suggest that in 1398, as Timur’s forces approached Ajodhan (Pakpattan), he learned of the revered shrine of the Sufi saint Baba Farid and the deep veneration held for him by the local community.[41] Acknowledging Baba Farid’s spiritual significance, Timur visited the shrine to pray for strength and, out of respect for the saint’s legacy, spared the town’s remaining inhabitants who had not fled his advance.[39] [42] [43] [44] During Timur's 1398 invasion, numerous inhabitants of Ajodhan (Pakpattan) and Dipalpur, fearing his advancing forces, fled their cities and sought refuge in the fortified town of Bhatner (present-day Hanumangarh), believing that Bhatner's strong defenses and remote location would offer protection from invaders.[45] In his memoir, Timur recorded:

I appointed Amir Shah Malik and Daulut Timur Tawachi to march forward with a large army, by way of Dibalpur, towards Dehli, and ordered them to wait for me at Samana, which is a place in the neighbourhood of Dehli. I. mysell, in the meanwhile, pushed forward upon Bhatnir with a body of 10,000 picked cavalry. On arriving at Ajodhan, I found that among the shaikhs of this place (who, except the name of Shaikh, have nothing of piety or devotion about them) there was a shaikh named Manua, who, seducing some of the inhabitants of this city, had induced them to desert their country and accompany him towards Dehli, while some, tempted by Shaikh Sa'd; his companion, had gone to Bhatnir, and a number of the wise men of religion and the doctors of law of Islam, who always keep the foot of resignation firmly fixed in the road of destiny, had not moved from their places, but remained quietly at home.

On my arrival in the neighbourhood of Ajodhan, they all hastened forth to meet me, and were honoured by kissing my footstool, and I dismissed them after treating them with great honour and respect. I appointed my slave, Nasiru-d din, and Shahab Mubammad to see that no injury was inflicted by my troops on the people of this city. I was informed that the blessed tomb of Hazrat Shaikh Farid Ganj-shakar (whom may God bless) was in this city, upon which I immediately set out on pilgrimage to it. I repeated the Fatiha, and the other prayers, for assistance, etc., and prayed for victory from his blessed spirit, and distributed large sums in alms and charity among the attendants on the holy shrine. I left Ajodhan on Wednesday, the 26th of the month, on my march to Bhatnir...The people of the country informed me that Bhatnir was about fifty kos off, and that it was an extremely strong and well-fortified place, so much so as to be renowned throughout the whole of Hindustan....The people who had fled from Ajodhan had come to Bhatnir, because no hostile army had ever penetrated thither. So a great concourse of people from Dibalpur and Ajodhan, with much property and valuables, was there assembled.[46]

15th Century

[edit]Khizr Khan defeated the armies of Firuz Shah Tughlaq of the Delhi Sultanate in battles outside of Ajodhan (Pakpattan) between 1401 and 1405.[39]

The town continued to grow as the reputation and influence of the Baba Farid shrine spread, but was also bolstered by its privileged position along the Multan to Delhi trade route.[47] The shrine's importance began to outweigh that of Ajodhan itself, and the town was subsequently renamed "Pakpattan" in honor of a ferry service over the Sutlej River.[6]

Taxation and Religious Policies in Medieval Pakpattan

[edit]Overall, during the medieval period, Pakpattan emerged as a significant center of Sufism, particularly due to the influence of the revered Sufi saint Baba Farid (1173–1266 CE). As part of broader efforts by Islamic rulers to consolidate their authority, various measures were employed to promote Islam and regulate the administration of non-Muslim populations in the region.[48] These measures often included taxation policies, such as the jizya tax, as well as efforts to spread Islam through other administrative and coercive means.[49][50]

Under the Delhi Sultanate (13th–16th century), jizya was rigorously enforced by rulers such as Alauddin Khalji (1296–1316), who implemented it as part of his economic and administrative policies.[51] Later, Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1351–1388) and Sikandar Lodi (1489–1517) reinforced the imposition of Islamic laws, including jizya, throughout their territories, including Pakpattan.[52] Non-Muslims who converted to Islam were often exempt from jizya, an incentive that likely influenced conversions.[53]

In addition to taxation, Sufi missionaries, particularly Baba Farid and his successors, were instrumental in promoting Islam in the region. Encouraged by Islamic rulers, Sufi saints played a key role in converting non-Muslims, including Hindus, by establishing spiritual centers and engaging in discourse. Baba Farid’s dargah (shrine) became a focal point for spreading Islamic beliefs.[54] Reflecting the general trend in Punjab during this period, while numerous Hindus in Pakpattan likely embraced Islam due to these policies—forming the ancestry of much of the city’s present-day Muslim residents—many Hindu communities remained resilient, up through the 1947 partition, preserving their cultural and religious practices under changing regimes.[55]

Mughal period (16th and 17th centuries)

[edit]Early 16th Century

[edit]The founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak, visited the town in the early 1500s to collect compositions of Baba Farid's poetry.[56] The exact date of Guru Nanak's visit to Ajodhan (Pakpattan) is traditionally placed around 1510-1511 CE, during his first major journey across the Indian subcontinent.[57] Though Baba Farid had passed away over two centuries prior, Guru Nanak’s respect for Sufi teachings led him to the saint's shrine, where he engaged in spiritual discourse with Sheikh Ibrahim, a descendant of Baba Farid and the head of the shrine at the time.[57]

Mughal rule

[edit]During the Mughal era in the 16th and 17th centuries, the Shrine of Baba Farid in Pakpattan received significant royal patronage, enhancing its prominence as a center of Sufism. Emperor Akbar (1556–1605), during his visit to the shrine in the late 16th century, renamed the town from Ajodhan to Pakpattan, meaning "Pure Ferry," reflecting the town's spiritual significance.[58] His son, Jahangir, continued this tradition as Emperor by offering support to the shrine and its custodians.

In 1692, Emperor Shah Jahan further solidified the shrine's status by bestowing royal support upon its Dewan chief and the descendants of Baba Farid, who became known as the Chishtis. The shrine and Chistis were defended by an army of devotees drawn from local Jat clans.[5] The patronage not only elevated the shrine's stature but also reinforced Pakpattan's role as a key center of Sufism during the Mughal era.

Notably, under the Mughal Empire, the imposition of jizya upon the Hindu residents of Pakpattan varied depending on the ruler's policies. Akbar abolished the tax in 1564 as part of his religiously tolerant policies, providing relief to non-Muslim residents of Pakpattan.[59] However, Aurangzeb (1658–1707) reintroduced jizya in 1679 as part of his conservative Islamic reforms, significantly affecting Hindu communities in the region.[60] His reign also saw restrictions on Hindu rituals and festivals in Punjab which likely affected the residents of Pakpattan, further influencing the region's religious landscape.[61]

Pakpattan’s history reflects the interplay of taxation policies and religious efforts by rulers to consolidate their authority while shaping the cultural and spiritual fabric of the region. Despite these pressures, the Hindu communities' resilience, combined with the evolving policies of successive regimes, ensured the preservation of their cultural identity and traditions.

Pakpattan state (1692–1810 CE)

[edit]Following the disintegration of the Mughal Empire, the shrine's Diwan was able to forge a political independent state centered on Pakpattan.[5] In 1757, the territory of the Pakpattan state was extended across the Sutlej River after the shrine's head raised an army against the Raja of Bikaner.[5] The shrine's army was able to repel a 1776 attack by the Sikh Nakai Misl state, resulting in the death of the Nakai leader, Heera Singh Sandhu.[5]

Sikh rule

[edit]Maharaja Ranjit Singh (1799–1839) of the Sikh Empire seized Pakpattan in 1810, removing the political autonomy of the Baba Farid shrine’s chief.[5] In his efforts to centralize power across Punjab, Maharaja Ranjit Singh systematically reduced the autonomy of regional spiritual and administrative leaders, including the Dewan of the Baba Farid shrine in Pakpattan. Historical accounts suggest that upon Maharaja Ranjit Singh's capture of the town, the Dewan presented the Maharaja with a sword, a horse, cash, and reportedly women, as part of a customary tribute to demonstrate loyalty and seek favor.[62] Such gestures reflected the feudal and patriarchal norms of the time, with symbolic and practical items like swords and horses representing martial allegiance.[63] Ranjit Singh diminished the shrine’s independence by integrating its resources and influence into his administration, reflecting his broader strategy of consolidating control over both religious and secular institutions in his empire.[64]

Ranjit Singh maintained a deep respect for the shrine’s significance, particularly because Baba Farid’s spiritual poetry is included in the Sikh holy text, the Guru Granth Sahib.[65] To honor the shrine, Ranjit Singh provided it with an annual nazrana (allowance) of 9,000 rupees and granted tracts of land to Baba Farid’s descendants.[66] [65] Through this patronage, he not only demonstrated his reverence for the shrine’s spiritual importance but also reinforced his legitimacy as a ruler among diverse religious communities.[67] Supporting the shrine enabled him to extend his influence throughout the Pakpattan shrine's spiritual wilayat (territory) and its network of smaller shrines, strengthening his rule as a non-Muslim leader in a region with profound religious significance.[66] [67]

Under Maharaja Ranjit Singh, state policies generally shifted toward greater religious tolerance. Discriminatory taxes such as jizya were abolished, and both Hindu and Sikh communities in Pakpattan were allowed to freely practice their faiths without external pressures to convert.[68] The abolition of jizya symbolized a significant shift in governance, fostering greater equality and inclusivity for non-Muslim residents.

In one anecdotal instance, during Maharaja Ranjit Singh's rule in Pakpattan, a local disturbance arose following the news of a cow, sacred to Hindus, being slaughtered by some Muslim residents. To pacify tensions and promote communal harmony, Ranjit Singh instituted a system during the Baba Farid shrine's mela (festival) time where the key to the shrine would remain with a Hindu throughout the night. The shrine would open at 5 a.m. and close at 6 p.m. daily. The Hindu would hand the key to a Sikh in the morning, who would pass it to the Dewan (a Muslim) to open the shrine, after which the Dewan would return the key to the Sikh, who would then give it back to the Hindu. This symbolic chain of custody emphasized communal cooperation and mutual respect.

Additionally, Ranjit Singh assigned different parts of the city to different communities in a balanced manner—for instance, allocating the Gala Mandi to Hindus, another area to Sikhs, and others to Muslims—ensuring equitable representation and fostering a sense of shared community.

Notable Historical Visits to Pakpattan (997–1810 CE)

[edit]Several historical figures are recorded or traditionally believed to have visited Pakpattan (formerly Ajodhan), drawn by the spiritual significance of Baba Farid’s shrine, a prominent Sufi center. These visits highlight Pakpattan's enduring importance as a hub of spirituality and influence, attracting rulers, poets, and spiritual leaders seeking blessings, political legitimacy, or personal guidance.

Pakpattan’s old city (the Dhakki area that contains the shrine), became a nexus of spiritual and temporal power. Sufi teachings influenced governance, ethics, and social justice, while rulers often sought to strengthen their authority through association with Sufi saints. The town fostered cultural exchange, intellectual enrichment, and dialogue among diverse communities, becoming a center where mystics, scholars, and travelers converged.

However, Pakpattan’s prominence also drew the attention of brutal rulers who instilled fear among its residents, underscoring the city’s vulnerability amidst its prominence. Despite this, its reputation as a dynamic space where spirituality, politics, and culture intersected endured, leaving a lasting impact on the region’s historical and cultural fabric.

| Historical Figure | Title/Position | Date/Period of Visit | Context of Visit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sabuktagin | Founder of the Ghaznavid Dynasty, Mahmud’s father | Late 10th century (c. 997) | Sabuktagin’s expansionist ambitions brought him into the Punjab region, including Ajodhan (Pakpattan), as he laid the groundwork for further invasions into India by his son Mahmud.[69] |

| Mahmud of Ghazni | Sultan of the Ghaznavid Empire | Early 11th century (c. 1005-1010) | Mahmud of Ghazni, notorious for his ruthless raids and desecration of Hindu temples, likely stopped at Ajodhan (Pakpattan) during his campaigns, which were often marked by fierce intolerance toward local religions and cultures.[69] |

| ltutmish | Sultan of Delhi | 1211–1236 CE | Sultan Itutmish reportedly visited Ajodhan to seek blessings from Baba Farid and strengthen ties with influential Sufi leaders, acknowledging their spiritual and social power. |

| Sultan Ghiyas ud din Balban | Sultan of Delhi Sultanate | 13th century (c. 1260-1287) | Balban, known for his strict governance and emphasis on order, is believed to have visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) as part of his campaigns to assert control over the region. His visit included a stop at the shrine of Baba Farid, reflecting the political and spiritual significance of the site.[70] |

| Sultan Jalal-ud-din Khilji | Sultan of Delhi Sultanate | 1290–1296 | Sultan Jalal-ud-din Khilji visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to seek blessings from Baba Farid’s shrine and strengthen spiritual connections.[71] |

| Amir Khusrau | Sufi poet, musician, scholar | Late 13th–early 14th century | The renowned poet and disciple of Nizamuddin Auliya, Amir Khusrau, is believed to have visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to pay his respects to Baba Farid.[72] |

| Muhammad bin Tughlaq | Sultan of Delhi Sultanate | Mid-14th century (c. 1335) | Muhammad bin Tughlaq, known for his erratic and often harsh rule, visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to maintain political control in Punjab and likely sought support from local Sufi figures for stability.[73] |

| Ibn Battuta | Moroccan explorer and scholar | 1333 | Ibn Battuta, during his travels across India, visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) and documented the importance of the shrine of Baba Farid, noting the spiritual significance of the site and its influence across the region.[74] |

| Feroz Shah Tughlaq | Sultan of Delhi Sultanate | 1351–1388 | Known for his reverence for Sufi saints, Feroz Shah Tughlaq visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) and contributed to the upkeep of Baba Farid’s shrine.[75] |

| Timur (Tamerlane) | Conqueror and founder of the Timurid Empire | 1398 | During his violent invasion of India, Timur passed through the Punjab region and visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan), sparing the city's residents out of respect for the shrine of Baba Farid, even as he left a path of destruction on his advance toward Delhi.[76] |

| Guru Nanak | Founder of Sikhism | Early 16th century (c. 1505) | Guru Nanak visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to meet Sheikh Ibrahim, the 12th successor of Baba Farid, engaging in spiritual discussions that emphasized compassion and tolerance.[77] |

| Ibrahim Lodhi | Sultan of Delhi Sultanate | Early 16th century (c. 1510-1526) | Ibrahim Lodhi, the last Sultan of the Delhi Sultanate, reportedly visited the shrine of Baba Farid in Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to strengthen his ties with spiritual leaders during a time of political instability.[78] |

| Babur | Founder of Mughal Empire | 1524 | Babur likely passed through Pakpattan during his 1524 CE Punjab campaign. While his memoir, the Baburnama, does not explicitly mention Pakpattan, historical records suggest his forces traversed key areas, including this spiritual center known for the shrine of Sufi saint Baba Fariduddin Ganjshakar.[79] [80] Pakpattan’s strategic location along major routes made it a natural waypoint for his army, though it was not a primary military target.[81] [82] As a brutal tyrant, his campaigns were defined by unrelenting military aggression and widespread acts of brutality against resisting forces and religious communities.[82] [83] |

| Sher Shah Suri | Founder of the Suri Empire | Mid-16th century (c. 1540) | Sher Shah Suri visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) during his consolidation of power in Punjab. While primarily a pragmatic ruler, his campaigns often included brutal enforcement against opposing forces.[84] |

| Mughal Emperor Akbar | Emperor of the Mughal Empire | 1571 or 1577-1579 | Emperor Akbar visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to pay respects at the shrine of Baba Farid during his campaigns in the region, using his influence over Sufi saints to bolster his rule.[85] According to historical accounts, after Emperor Akbar's visit to Pakpattan in 1577, his entourage encountered excessive rainfall.[86] |

| Nawab Qutb-ud-din Khan Koka | Mughal governor of Punjab | Late 16th–early 17th century | Nawab Qutb-ud-din Khan Koka, a prominent Mughal governor, visited Ajodhan (Pakpattan) as part of his administrative duties, paying respects at the shrine of Baba Farid to solidify his influence in the region.[87] |

| Shah Jahan | Emperor of the Mughal Empire | 1628–1658 | Shah Jahan, in line with the Mughal tradition of patronizing Sufi shrines, is believed to have visited the shrine of Baba Farid in Ajodhan (Pakpattan) to seek blessings and affirm spiritual and political authority.[88] |

| Aurangzeb | Emperor of the Mughal Empire | 1658–1707 | Emperor Aurangzeb, notorious for his brutal policies that led to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of Hindus and widespread forced conversions to Islam, visited Baba Farid’s shrine in Pakpattan, reflecting his interest in reinforcing political and religious authority through connections with prominent Sufi centers.[89] [90] |

| Bahadur Shah I | Emperor of the Mughal Empire | 1707–1712 | Bahadur Shah I, known for his affiliation with Sufi orders, visited Pakpattan to seek blessings from Baba Farid’s shrine and strengthen his ties with spiritual leaders in Punjab.[91] |

| Maharaja Ranjit Singh | Ruler of the Sikh Empire | Early 19th century (c. 1810) | Ranjit Singh visited Pakpattan to honor the shrine of Baba Farid, reinforcing his respect for Punjab's diverse spiritual heritage and his connections with local religious leaders.[92] |

British rule

[edit]Following the establishment of British rule in Punjab after defeating the Sikh Empire, Pakpattan in 1849 was made district headquarters, before it was shifted in 1852, and finally to Montgomery (now Sahiwal) in 1856.[93] The Pakpattan Municipal Council was established in 1868,[93] and the population in 1901 was 6,192. Income in the era chiefly derived from transit fees.[26]

Between the 1890s and 1920s, the British laid a vast network of canals in region around Pakpattan, and throughout much of central and southern Punjab province,[94] leading to the establishment of dozens of new villages around Pakpattan. In 1910, the Lodhran–Khanewal Branch Line was laid, making Pakpattan an important stop before the railway was dismantled and shipped to Iraq.[93] In the 1940s, Pakpattan became a centre for Muslim League politics, as the shrine granted the League privileges to address crowds at the urs fair in 1945 - a favour not granted to pro-Unionist parties.[95] The shrine's sajjada nasheen caretakers further refused to sign an anti-Partition manifesto brought to them by pro-Unionists.[95]

Pakpattan received electricity in 1942 during British rule, as part of efforts to modernize infrastructure in the region before the partition of India in 1947.[96]

Partition (1947)

[edit]

Just prior to the partition of 1947, the city's population included a substantial number of Hindus and Sikhs.[97][98] Some well-known local residents at the time included Bhasheshar Nath (a major landowner), Dr. Ram Nath (MBBS doctor), and Lala Ganpat Rai Dhawan (local businessman and patwari). The Hindus of the city controlled much of the commerce and banking.[97]

On August 15, 1947, a major communal clash was supposed to take place but the Hindus left Pakpattan a few days later through the Sulemanki route.[97] On August 23 and 24, looting had begun, and more of city's Hindus and Sikhs left the next day.[97] Overall, although there were some deaths, the numbers were relatively low compared to other cities in Punjab.[97] However, during that summer, a train departing from Pakpattan Railway Station carrying Hindus and Sikhs was attacked shortly after leaving, resulting in all the passengers being slaughtered by a Muslim mob.[99] Among those on the train was Sardar Kartar Singh, the brother of Sir Datar Singh (maternal grandfather of Indian politician Maneka Gandhi). Kartar Singh was traveling with his young wife and daughter when the train was ambushed approximately 5 kilometers from Pakpattan. Both Kartar Singh and his wife were killed in the attack, but their daughter survived. She was later adopted by a Muslim family in Pakistan, who cared for her for over a year. Eventually, a family member from India traveled to Pakistan and brought her back, reuniting her with her extended family.

The city's Hindu and Sikh population fled to various areas in India (notably Fazilka) and was replaced by Muslim migrants from India (notably from towns such as Hoshiarpur and Fazilka).

The stories of partition as told by the city's elderly residents who lived through the partition, have been extensively documented by Ahmad Naeem Chishti, in the social media page Partition Diary.[100]

Modern

[edit]Pakpattan's demography was radically altered by the Partition of British Raj, with the vast majority of its Sikh and Hindu residents migrating to India. Several Chisti scholars and notable families also settled in the city, having fled from regions that were allocated to India. Pakpattan thus increased in importance as a religious centre, and witnessed the development of pir-muridi shrine culture.[101] The influence of the shrine's caretakers grew as Chistis and their devotees congregated in the city to such a degree that the shrine caretakers are regarded as "kingmakers" for local and regional politics.[101] Pakpattan's shrine continued to grow in influence as Pakistani Muslims found it increasingly difficult to visit other Chisti shrines that now lay in India,[101] while Sikhs in India commemorate Baba Farid's urs in absentia at Amritsar.[102] Pakpattan continues to be a major pilgrimage centre, drawing up to 2 million annual visitors its large urs festival.[4]

Demographics

[edit]

According to the 1998 Pakistan Census, the population of Pakpattan city was recorded as 109,033. As per 2017 Census of Pakistan, the population of city was recorded as 176,693 with an increase of 62.05% in just 19 years.[103]

Language

[edit]Punjabi is the native spoken language but Urdu is also widely understood and spoken. Haryanvi also called Rangari is spoken among Ranghars . Meo have their own language which is called Mewati.

Shrine of Baba Farid

[edit]

The Shrine of Baba Farid is one of Pakistan's most revered shrines. Built in the town once known in medieval times as Ajodhan, the shrine became so well-known that the area was renamed "Pakpattan," meaning "Holy Ferry," in reference to a river crossing made by pilgrims to reach the shrine.[104] The shrine has since been a key factor shaping Pakpattan's economy, and the city's politics. [104]

The revered sanctuary is dedicated to Hazrat Baba Farid-ud-Din Masood Ganj Shakar, a prominent 13th-century Sufi saint of the Chishti Order. Known for his spiritual teachings and Punjabi poetry, Baba Farid's shrine attracts thousands of visitors annually, particularly during the Urs (death anniversary) celebrations. The shrine complex, known for its historical and architectural significance, includes a grand gateway, courtyards, and the saint's tomb. It is also home to the Bahishti Darwaza ("Gate to Paradise"), a symbolic portal believed to grant blessings to those who pass through it.

Other Shrines in Pakpatan

[edit]In addition to the renowned shrine of Baba Fariduddin Ganjshakar, Pakpattan is home to several other significant shrines that contribute to the city's rich spiritual heritage. These shrines attract devotees from across the region, reflecting the enduring Sufi traditions of the area:

- Darbar Hazrat Khawaja Aziz Makki Sarkar: This shrine honors Hazrat Khawaja Aziz Makki, a revered Sufi saint whose teachings have had a lasting impact on the region's spiritual landscape. The site attracts numerous devotees seeking spiritual guidance and blessings.[105] [106]

- Shrine of Khawaja Amoor ul Hasan: Dedicated to Khawaja Amoor ul Hasan, a prominent figure in the Chishti Order of Sufism, this shrine highlights his spiritual contributions. After migrating from Saharanpur to Pakpattan during the 1947 partition, he continued his spiritual mission until his passing in 1986.[107]

- Shrine of Bibi Raj Kaur: Known as the sister of Baba Farid, this shrine honors her piety and connection to the great Sufi saint. It is a site of reverence, particularly for women seeking blessings.

- Shrine of Sheikh Muhammad Chishti: Associated with one of Baba Farid's disciples, this shrine serves as a testament to the role of Sufi saints in spreading Islamic teachings in the region.

- Shrine of Hakeem Ghulam Muhammad: Located in the heart of Pakpattan, this shrine commemorates a local scholar and mystic, highlighting the city's legacy of Islamic learning and spirituality.

These shrines, though smaller in scale than Baba Farid’s, play an integral role in Pakpattan’s identity as a hub of Sufism and spiritual culture. Pilgrims often visit these sites as part of their journey to the city, contributing to its historical and cultural significance.

Culture

[edit]Pakpattan’s culture is deeply intertwined with its rich history and spiritual heritage, shaped by centuries of Sufi traditions and religious diversity. The city is renowned for the shrine of Baba Fariduddin Ganjshakar, a prominent figure in the Chishti Sufi Order, whose teachings of love, tolerance, and humility have left a lasting impact on the community. The annual Urs festival in Baba Farid’s honor draws thousands of pilgrims from across the region, transforming the city into a vibrant hub of religious devotion and cultural activity. During the festival, Pakpattan comes alive with qawwali performances, food stalls, and colorful processions, embodying the city’s deep connection to Sufism.

Traditional clothing, such as the shalwar kameez for both men and women, reflects the city’s adherence to Punjabi cultural norms. Pakpattan has a history of producing handcrafted items, including embroidered textiles and leather goods, which showcase the artisan traditions of the region. The local cuisine also reflects its agrarian roots, featuring dishes made from fresh produce, dairy, and wheat. Popular foods include lassi, parathas, and sweets like gulab jamun and jalebi, which are widely enjoyed during festivals and family gatherings. Street food stalls further enhance the culinary landscape, particularly during the Urs festival.

Sufi poetry and music are integral to Pakpattan’s cultural identity. The verses of Baba Farid, often recited at the shrine and in religious gatherings, remain a cornerstone of the city’s spiritual life. Qawwali performances at cultural events highlight Pakpattan’s connection to mystical music traditions. Architecturally, the Dhakki (Old City) area and remnants of pre-partition Hindu and Sikh communities serve as silent witnesses to Pakpattan’s diverse history, adding to its cultural legacy.

Despite modernization, Pakpattan continues to preserve its traditional values while adapting to contemporary influences. Its spiritual essence, combined with its vibrant festivals, artisanal crafts, and culinary delights, ensures its enduring significance in the cultural landscape of Punjab.

Famous Food

[edit]Tosha is a traditional sweet first produced in Pakpattan, deeply rooted in the city’s cultural and spiritual history.[108] [109] Associated with the Shrine of Baba Farid, it has long been prepared as a devotional offering and holds a special place in the region’s Sufi traditions.[109] Made by deep-frying and immersing in sugary syrup, tosha combines a crisp exterior with a syrupy center, symbolizing Pakpattan’s rich heritage.

Following the Partition of India in 1947, tosha's legacy extended across borders.[110] A sweet maker from Pakpattan, Lala Munshi Ram, brought the recipe to Fazilka, India, where it became a popular delicacy sold under the name Pakpattnian Di Hatti ("The Shop of the People of Pakpattan").[109] Today, tosha remains celebrated in both Pakistan and India as a symbol of shared culinary and cultural traditions, linking communities through its unique flavor and historical significance.

Dhakki (old city) area

[edit]

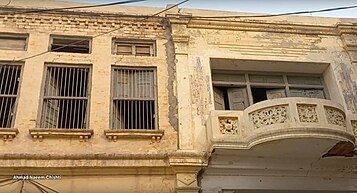

Pakpattan's historic Dhakki—meaning mound, small hill, or high place—sits at an elevated level as the original heart of the city, which later expanded outward.[111][98] This elevated neighborhood, which first housed the earliest residents of Ajodhan (Pakpattan), features narrow, winding streets that once thrived as a bustling hub of diverse communities. Steeped in thousands of years of history, Dhakki was once fortified with six large gates that closed at night to protect its inhabitants. The gates served as crucial entry points to the walled city, playing a significant role in Pakpattan's defense and facilitating trade. Today, only four of these ancient gates—Shahedi, Rehimun, Abu, and Mohri—still stand, each in a state of decay, offering a fading glimpse into the past.[98] [112] Mohri Gate, believed to be over 400 years old, stands today, named for its "Mohri," or opening, through which one could see.[113] It was also known as "Handa Walla" gate due to the presence of Handa families living nearby, further linking the gate to the community it once served.[113]

The Dhakki area also holds significant architectural remnants from various eras. A notable remnant in this area is part of the wall of the 'Kacha Burj,' a defensive fort built by Sher Shah Suri; after conquering the city in 1541, Suri tasked his general, Haibat Khan, with constructing the fort to guard against potential invaders.[111][114] This fortification and the Dhakki’s layout reflect the strategic importance of Pakpattan as a settlement and its role in defending against invasions throughout history. Given that the Dhakki area is home to the renowned Shrine of Baba Farid, numerous historical figures have journeyed here over the centuries as they paid homage to the shrine.

Before the 1947 Partition, Dhakki was primarily home to Hindu families, particularly Khatris, including the Dhawan, Handa, and Chopra families. Today, several pre-partition houses still stand in Dhakki, preserving the history of that era. Notably, one of the residents of Dhakki before 1947 was Sardar Kartar Singh, the brother of Sir Datar Singh, who was the maternal grandfather of Indian politician Maneka Gandhi, a senior member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

Today, as visitors wander through Dhakki, the surviving gates, narrow passageways, and historic homes echo Pakpattan’s rich legacy, connecting the past to the present in an area that remains a cultural and historical landmark of the city.

Other parts of the City

[edit]

At the base of Dhakki lies Smadhan Walla Mohalla, once home to numerous Hindu "smadhs" (memorial sites). Today, the area hosts the Government Faridia Graduate College, Pakpattan, built on a site where iconic and historic smadhs once stood before the Partition. Remnants of a pond with deep stairs, used for religious and communal purposes, remain intact, serving as a quiet testament to the area's vibrant past. The old havelis of Hindus and Sikhs, including those of Basheshar Nath, Boota Ram, and Dr. Ram Nath, stand as architectural relics, reflecting the diverse pre-Partition communities that once thrived in Pakpattan.

The city's railway station, with its iconic colonial-era building, is surrounded by structures that speak to its historical significance during British rule. These include officers' quarters, a hospital, and a rest house, all of which echo the city’s colonial heritage. The station played a crucial role in connecting Pakpattan to other regions, facilitating trade, pilgrimage, and migration, particularly during the tumultuous Partition period.

Other areas of Pakpattan reveal a blend of old and new. The central bazaar, located near Dhakki, remains a bustling commercial hub where traditional shops and markets coexist with modern businesses. Narrow lanes lined with old, crumbling buildings and newer constructions showcase the evolving urban landscape of the city. Many streets and neighborhoods retain names reflecting their historical or cultural roots, serving as living reminders of the city's diverse past.

Residential expansion beyond the historic core has transformed Pakpattan into a more urbanized area, with modern housing colonies and commercial centers gradually shaping its outskirts. However, remnants of older neighborhoods still preserve the charm of an era where communities lived in close-knit, shared spaces.

The Sutlej River plays a vital role in the city's geography and history. While much of the river's activity centers on agriculture and irrigation, the areas near its banks provide scenic views and are often associated with local folklore and spirituality, further tying the modern city to its historical and cultural identity.

Economy

[edit]The economy of Pakpattan is primarily based on agriculture, religious tourism, and small-scale industries, with trade serving as a key livelihood for residents. Located in Punjab's fertile plains, Pakpattan benefits from irrigation via the Sutlej River, making agriculture the backbone of its economy. Key crops include wheat, rice, sugarcane, and cotton, with dairy farming also contributing significantly to local production.

Religious tourism, centered around the shrine of Baba Farid, draws thousands of pilgrims annually, especially during the Urs festival. This influx boosts the local economy, supporting businesses such as hotels, guesthouses, food vendors, and shops selling handicrafts and religious items.

Small-scale industries, including flour and rice mills and cottage industries, complement the economy by catering to local and regional markets. The central bazaar acts as a commercial hub for agricultural inputs, consumer goods, and daily necessities. Emerging sectors such as tourism infrastructure and real estate are also gaining momentum, although challenges like limited industrial growth and seasonal unemployment persist. Addressing these issues through improved infrastructure and development projects could enhance Pakpattan’s economic potential.

Education

[edit]Pakpattan hosts a diverse range of educational institutions catering to students from primary to higher education levels. The city includes both government and private institutions that aim to provide accessible and quality education across various fields. Notable schools include Government Boys High School Pakpattan and Government Girls High School Pakpattan, which play a significant role in community education. Private institutions, such as Pakpattan Public School, focus on fostering academic excellence and character development.

For higher education, the Government Faridia Postgraduate College, named after the Sufi saint Baba Farid, stands as a prominent institution. It offers undergraduate and postgraduate programs in arts, science, commerce, and humanities. The college is equipped with modern facilities, including laboratories, a library, and spaces for extracurricular activities, creating a well-rounded academic environment. Additionally, vocational and technical training centers in Pakpattan provide specialized courses to prepare students with practical skills for the job market.

Despite these advancements, Pakpattan’s education system still faces challenges. The literacy rate, while improving, remains below the national average, especially in rural areas. Many schools struggle with inadequate infrastructure, insufficient teacher training, and limited access to modern educational resources. Access to quality education, particularly for girls, remains a pressing concern due to socio-cultural and economic barriers. Recent initiatives by the government and non-governmental organizations aim to address these issues by promoting teacher training programs, constructing new schools, and encouraging female enrollment. These efforts, alongside the existing institutions, contribute to the city’s educational development and empower its residents.

Healthcare

[edit]Healthcare services in Pakpattan are limited, particularly in rural areas where residents often struggle to access basic medical care. The city’s healthcare infrastructure includes a District Headquarters (DHQ) Hospital, several smaller public hospitals, and private clinics. However, these facilities are often understaffed and lack the resources to cater to the growing population. Specialized medical services, such as cardiology, oncology, and advanced diagnostic tools, are either unavailable or accessible only in larger nearby cities. Public health challenges, such as malnutrition, infectious diseases, and inadequate maternal and child health services, are prevalent. Recent efforts by the provincial government and charitable organizations have aimed to improve healthcare delivery, including upgrading facilities, providing free vaccinations, and launching health awareness campaigns.

Challenges

[edit]Pakpattan faces several challenges that impact its cultural heritage, infrastructure, and development. The preservation of historical sites, such as the shrine of Baba Farid, is a major concern due to urban encroachment and insufficient conservation efforts, threatening the city's rich legacy. Rapid urbanization has strained infrastructure, with roads, sanitation systems, and public utilities struggling to keep pace with a growing population. Water management remains a significant issue, as inefficient irrigation practices and seasonal flooding disrupt agriculture and damage infrastructure, while water scarcity affects the local economy. Healthcare services are limited, particularly in rural areas, where medical facilities are underfunded and ill-equipped, and the city lacks sufficient specialized care facilities for its residents.

Environmental degradation, including deforestation, overuse of agricultural land, and improper waste disposal, contributes to public health risks and threatens the region’s biodiversity. Fire safety is another critical issue, as many areas lack adequate fire prevention measures and response systems, leaving both densely populated neighborhoods and heritage sites vulnerable. Economic growth is hindered by the absence of industrial diversification and limited employment opportunities, particularly for younger residents. Furthermore, Pakpattan’s status as a significant pilgrimage site brings its own challenges, with inadequate facilities and poor crowd management during events like the Urs of Baba Farid causing logistical and safety concerns.

Crime, while generally low in Pakpattan, presents challenges, particularly with petty offenses such as pickpocketing and theft in crowded areas. However, the local police have made significant strides in combating crime; for instance, in recent operations, Pakpattan Police apprehended 123 members of various notorious dacoit gangs and 1,065 proclaimed offenders, recovering valuables worth RS 2.4 crore (24 million).[115]

Despite these difficulties, the resilience and determination of Pakpattan’s residents shine through. Their commitment to preserving the city’s cultural heritage, supporting one another during crises, and striving for better opportunities underscores the enduring spirit of the community. Addressing these challenges is crucial for the sustainable development of the city while safeguarding its cultural and historical identity.

Recent Developments

[edit]As of November 2024, Pakpattan City has witnessed several notable events:

- Flooding in 2023: In August 2023, Pakpattan City was affected by heavy flooding from the Sutlej River, which caused water to inundate urban areas, damaging homes, roads, and local markets. The city experienced disruptions in transportation and trade, prompting local authorities and NGOs to coordinate relief efforts for affected residents.[116]

- Healthcare Expansion in 2024: In September 2024, a modern healthcare facility was inaugurated in Pakpattan City, aimed at addressing the growing medical needs of urban residents. The new hospital includes specialized wards and diagnostic facilities, improving access to healthcare for the city’s population.[117]

- Religious Tourism Surge in 2023: During the annual Urs festival of Baba Farid in October 2023, Pakpattan City saw an unprecedented number of pilgrims visiting the shrine. This surge in visitors boosted local businesses, including hotels, restaurants, and shops selling religious items. However, it also highlighted the need for better infrastructure to manage large crowds.[118]

- Market Fire Incident in 2024: In June 2024, a fire broke out in Pakpattan City’s main bazaar, destroying several shops and causing significant financial losses to local traders. Firefighters managed to control the blaze after several hours, but the incident raised concerns about the lack of fire safety measures in the city.[119]

- City Beautification in 2024: Pakpattan has seen significant progress under its first female Deputy Commissioner, Sadia Mehr, appointed in October 2023.[120] She has spearheaded city beautification and cleanup campaigns, launched solar-powered water supply projects in Arifwala, and implemented measures to control commodity prices and improve public services.[120] Her leadership reflects a commitment to enhancing infrastructure, essential services, and overall quality of life in the district.

These events underscore the dynamic nature of life in Pakpattan, highlighting both its challenges and progress in addressing urban issues and preserving its cultural significance.

References in Literature and Media

[edit]Pakpattan’s historical and spiritual significance has been prominently featured in various texts and media, underscoring its cultural and religious heritage. Documentaries and books on Sufism frequently highlight Pakpattan as a focal point for exploring the legacy of the Chishti Order. Television programs covering the annual Urs festival at Baba Farid’s shrine showcase the city’s vibrant religious and cultural traditions, drawing attention from both local and international audiences.

Pakpattan has also appeared in films and music. The 1960 Bollywood film Patang features the song "Yeh Duniya Patang", sung by Mohammed Rafi, where the lyrics reference "Pakpattan," symbolizing the city’s cultural resonance. Another iconic filmi song, "Pakpattan Tay Aan Kay", sung by the legendary Noor Jehan, highlights the city’s significance in Pakistani cinema and music. These artistic representations reflect Pakpattan’s enduring cultural and spiritual identity.

References

[edit]- ^ "PAKISTAN: Provinces and Major Cities". PAKISTAN: Provinces and Major Cities. citypopulation.de. Retrieved 4 May 2020.

- ^ "National Dialing Codes". Pakistan Telecommunication Company Limited. Retrieved 28 August 2014.

- ^ "Between pirs and politicians | TNS - The News on Sunday". tns.thenews.com.pk. Archived from the original on 2019-05-27. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ a b "Spiritual ecstasy: Devotees throng Baba Farid's urs in Pakpattan - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2018-01-22.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Richard M. Eaton (1984). Metcalf, Barbara Daly (ed.). Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520046603. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ a b c Meri, Josef (2005). Medieval Islamic Civilization: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. ISBN 9781135455965. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak. Ain-i-Akbari. Translated by H. Blochmann and Colonel H.S. Jarrett, Low Price Publications, 2006.

- ^ "Pakpattan". Archived from the original on 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2017-11-28.

- ^ Maps (Map). Google Maps.

- ^ "Harappa | Indus Valley, Ancient City, Civilization | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2024-11-27.

- ^ Giosan, Liviu, et al. (2012). "Fluvial landscapes of the Harappan civilization." Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 109(26): E1688–E1694. doi:10.1073/pnas.1112743109.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7591-0172-1.

- ^ Possehl, Gregory L. (2002). The indus civilization: a contemporary perspective. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press. ISBN 978-0-7591-0171-5.

- ^ Singh, U. (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India. Pearson.

- ^ Bryant, E. F. (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Rebus Community. (n.d.). Agriculture in the Vedic Civilization. Retrieved from https://press.rebus.community/historyoftech/chapter/agriculture-in-the-vedic-civilization/

- ^ Sharma, R. S. (1996). India's Ancient Past. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Sharma, R. S. (2007). Material Culture and Social Formations in Ancient India. Macmillan India.

- ^ Basham, A. L. (1967). The Wonder That Was India. Grove Press.

- ^ Habib, I., & Thakur, V. (2002). The Vedic Age. Tulika Books.

- ^ Suvorova, Anna; Suvorova, Professor of Indo-Islamic Culture and Head of Department of Asian Literatures Anna (22 July 2004). Muslim Saints of South Asia: The Eleventh to Fifteenth Centuries. Routledge. ISBN 9781134370061. Retrieved 20 April 2017.

- ^ a b Latif, Syad Muhammad. Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities. New Imperial Press, 1892.

- ^ a b c Singh, Khushwant. A History of the Sikhs: Volume 1, 1469–1839. Oxford University Press, 1993.

- ^ Qureshi, I.H. The Muslim Community of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent (610-1947): A Brief Historical Analysis. University of Karachi, 1977.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. India in the Persianate Age: 1000–1765. University of California Press, 2019.

- ^ a b Pakpattan - Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 19, p. 332

- ^ Panjab University Research Bulletin: Arts. The University. 1975.

- ^ Talbot, Ian (2013-12-16). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. ISBN 9781136790362.

- ^ Rozehnal, R. (2016-04-30). Islamic Sufism Unbound: Politics and Piety in Twenty-First Century Pakistan. Springer. ISBN 9780230605725.

- ^ a b Singh, Rishi (2015). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. SAGE India. ISBN 9789351505044. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Elliot, H. M., & Dowson, J. (1867–1877). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period (Vol. 3). London: Trübner & Co. Available at: https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.21211

- ^ a b Asher, Catherine B. (1992). Architecture of Mughal India. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org

- ^ a b International Journal of Multidisciplinary Research and Analysis (IJMRA). (2022). The Tughlaq dynasty and their patronage of Sufi shrines in South Asia. Retrieved from https://www.ijmra.us/project%20doc/2022/IJRSS_SEPTEMBER2022/IJRSS18Sept22-AM.pdf

- ^ Gibb, H. A. R. The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354. Vol. 4, Hakluyt Society, 1994.

- ^ Gibb, H. A. R. The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354. Vol. 4, Hakluyt Society, 1994.

- ^ Gibb, H. A. R. The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354. Vol. 4, Hakluyt Society, 1994.

- ^ The Travels of Ibn Battuta, trans. H.A.R. Gibb, 1994, Vol. III, pp. 777–778; Ross E. Dunn

- ^ The Adventures of Ibn Battuta: A Muslim Traveler of the 14th Century, 1986, pp. 184–185).

- ^ a b c Imperial gazetteer of India: provincial series. Supt. of Govt. Print. 1908.

- ^ a b Dowson, John Ed (1873). The History Of India, As Told By Its Own Historians, Vol.5.

- ^ Nizami, Khaliq Ahmad. The Life and Times of Shaikh Farid-Ud-Din Ganj-i-Shakar. Department of History, Aligarh Muslim University, 1955.

- ^ Hamadani, Agha Hussain (1986). The Frontier Policy of the Delhi Sultans. Atlantic Publishers & Distri.

- ^ Digby, Simon. "Sufi Saints and State Power in Medieval India." Modern Asian Studies, vol. 13, no. 1, 1979, pp. 109–136.

- ^ Metcalf, Barbara Daly (1984). Moral Conduct and Authority: The Place of Adab in South Asian Islam. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520046603.

- ^ Timur, Great Khan of the Mongols (1783). [Tuzukat-i Timuri. English and Persian]. Institutes political and military, written originally in the Mogul language, by the great Timour, first translated into Persian by Abu Taulib Alhusseini; and thence into English, with marginal notes, by Major Davy, ... and the whole work published with a preface, indexes, geographical notes, ... 1783. Internet Archive.

- ^ Elliot, H. M., & Dowson, J. (Eds.). (1867–1877). The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians: The Muhammadan Period (Vols. 1–8). London: Trübner & Co.

- ^ Ali, M. Athar (2006). Mughal India: Studies in Polity, Ideas, Society, and Culture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648607.

- ^ Hardy, Peter (1972). The Muslims of British India. Cambridge University Press. p. 15. ISBN 9780521098731.

The imposition of jizya and other taxation policies served as tools for consolidating authority over non-Muslim populations in medieval India.

- ^ Chandra, Satish (1996). Historiography, Religion, and State in Medieval India. Har-Anand Publications. p. 98. ISBN 9788124106458.

Jizya served not only as a fiscal tool but also as a marker of non-Muslim submission to Islamic rule.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Eaton, Richard M. (1993). The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780520080867.

Islamic rulers employed administrative reforms and sometimes coercive policies to establish dominance and promote Islam in newly incorporated regions.

- ^ Habib, Irfan (1999). Economic History of the Delhi Sultanate. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195648765.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Chandra, Satish (1997). Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals - Delhi Sultanat (1206-1526). Har-Anand Publications. ISBN 9788124104966.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Habib, Irfan (2011). Economic History of Medieval India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198077449.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Chishti, Khaliq Ahmad Nizami (2006). The Life and Times of Sheikh Fariduddin Ganj-i-Shakar. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195472797.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Eaton, Richard M. The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760. University of California Press, 1993.

- ^ Singh, Pashaura (2002-12-27). The Bhagats of the Guru Granth Sahib: Sikh Self-Definition and the Bhagat Bani. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199087723.

- ^ a b Singh, Khushwant. A History of the Sikhs, Vol. 1, Oxford University Press, 2004.

- ^ "Pakpattan: The Home of Baba Farid Ganj Shakar". 28 January 2009.

- ^ Smith, Vincent (1917). Akbar the Great Mogul, 1542-1605. Clarendon Press.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195664659.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Eaton, Richard M. (2004). Temple Desecration and Muslim States in Medieval India. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195664659.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: checksum (help) - ^ Grewal, J. S. The Sikhs of the Punjab. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- ^ Griffin, Lepel. Ranjit Singh. Clarendon Press, 1892.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant. Ranjit Singh: Maharaja of the Punjab. Oxford University Press, 1962.

- ^ a b Singh, Khushwant. Ranjit Singh: Maharaja of the Punjab. Penguin Books, 2009

- ^ a b Singh, Rishi (2015-04-23). State Formation and the Establishment of Non-Muslim Hegemony: Post-Mughal 19th-century Punjab. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351505044.

- ^ a b Latif, Syad Muhammad. History of the Punjab. Eurasia Publishing House, 1964.

- ^ Singh, Khushwant (2008). Ranjit Singh: Maharaja of the Punjab. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780143065432.

- ^ a b Bosworth, C.E. "The Ghaznavids". Edinburgh University Press, 1963.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam. Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press, 2008.

- ^ Jackson, Peter. "The Delhi Sultanate: A Political and Military History". Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Schimmel, Annemarie. "Islam in the Indian Subcontinent". E.J. Brill, 1980.

- ^ Jackson, Peter. "The Delhi Sultanate". Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Dunn, Ross E. The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, a Muslim Traveler of the Fourteenth Century. University of California Press, 1986.

- ^ Jackson, Peter. "The Delhi Sultanate". Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ^ Manz, Beatrice Forbes. "The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane". Cambridge University Press, 1999.

- ^ Singh, Nikky-Guninder Kaur. "The Name of My Beloved: Verses of the Sikh Gurus". HarperCollins, 2001.

- ^ Shukla, D.N. Medieval India and the World Beyond. National Book Trust, India, 1998.

- ^ Babur, Zahir-ud-Din Muhammad. The Baburnama: Memoirs of Babur, Prince and Emperor. Translated by Annette Susannah Beveridge, 1922.

- ^ Nizami, K.A. Some Aspects of Religion and Politics in India During the Thirteenth Century. Oxford University Press, 1961.

- ^ Khan, Iqtidar Alam. Historical Dictionary of Medieval India. Scarecrow Press, 2008.

- ^ a b Richards, J.F. The Mughal Empire (The New Cambridge History of India). Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- ^ Lal, K.S. The Legacy of Muslim Rule in India. Voice of India, 1992.

- ^ Qanungo, Kalika Ranjan. "Sher Shah and His Times". Orient Longmans, 1921.

- ^ Richards, John F. "The Mughal Empire". Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- ^ Fisher, Michael H. (2017). "Pilgrimage, Performance, and Peripatetic Kingship: Akbar’s Journeys to Ajmer and the Formation of the Mughal Empire." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 27, Issue 1, pp. 1–26. Cambridge University Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1356186316000396.

- ^ Chandra, Satish. Medieval India: From Sultanat to the Mughals. Har-Anand Publications, 2007.

- ^ Nath, R. History of Mughal Architecture. Abhinav Publications, 2005.

- ^ Latif, Syad Muhammad. "Lahore: Its History, Architectural Remains and Antiquities." New Imperial Press, 1892.

- ^ Eaton, Richard M. "The Rise of Islam and the Bengal Frontier, 1204–1760." University of California Press, 1993.

- ^ Chandra, Satish. Essays on Medieval Indian History. Oxford University Press, 2003.

- ^ Grewal, J.S. "The Sikhs of the Punjab". Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- ^ a b c Nadiem, Ihsan H. (2005). Punjab: land, history, people. al-Faisal Nashran. ISBN 9789695032831.

- ^ Glover, William J. (2008). Making Lahore Modern: Constructing and Imagining a Colonial City. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9781452913384.

- ^ a b Talbot, Ian (2013-12-16). Khizr Tiwana, the Punjab Unionist Party and the Partition of India. Routledge. ISBN 9781136790362.

- ^ "Collections".

- ^ a b c d e Ahmed, Ishtiaq (2022). The Punjab Bloodied, Partitioned and Cleansed: Unravelling the 1947 Tragedy through Secret British Reports and First-Person Accounts. India: Rupa Publ iCat Ions India. pp. 510–511. ISBN 978-9355205780.

- ^ a b c "Our History Old City". Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ Train tragedy Pakpattan 1947 #punjab. Retrieved 2024-05-19 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ Chishti, Ahmad (August 11, 2022). "Partition Diary – a longing for revisiting hometown". The Dawn. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c Boivin, Michel; Delage, Remy (2015-12-22). Devotional Islam in Contemporary South Asia: Shrines, Journeys and Wanderers. Routledge. ISBN 9781317380009.

- ^ "Celebrating Urs in Amritsar". The Tribune.

- ^ "Pakistan: Provinces and Major Cities - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". www.citypopulation.de.

- ^ a b Mubeen, Muhammad (2015). Delage, Remy; Boivin, Michel (eds.). Devotional Islam in Contemporary South Asia: Shrines, Journeys and Wanderers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1317379997.

- ^ "Pakpattan Sharif (Pakistan): History of Pakpattan". 12 December 2009.

- ^ Shrines of Punjab | url=https://auqaf.punjab.gov.pk/shrines | website=Auqaf Punjab | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ Khawaja Amoor ul Hasan | url=https://en.everybodywiki.com/Khwaja_Amoor_Ul_Hasan | website=EverybodyWiki | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ "About Pakpattan". Pakpattan Social Media.

- ^ a b c "A Wistful Culinary Journey Tracing the History of 'Tosha'". 14 August 2024.

- ^ "Tosha from Pakpattan". punjabtourism.gov.in.

- ^ a b Chishti, Ahmad (December 3, 2023). "Pakpattan Dhakki Ancient & Historical City of Punjab". YouTube. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ https://pakpattan.punjab.gov.pk/our-history

- ^ a b Pakpattan dhakki da Mori Gate #punjab. Retrieved 2024-11-29 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "Historical places in Pakpattan Kacha Burj Dhaki". YouTube. December 3, 2023. Retrieved December 3, 2023.

- ^ https://punjabpolice.gov.pk/node/14837?utm_source=chatgpt.com

- ^ url=https://dunyanews.tv/en/Pakistan/749418-Flood-torrents-continue-playing-havoc-in-Pakpattan | website=Dunya News | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ Pakpattan gets modern hospital | url=https://www.dawn.com/news/1870534 | website=Dawn | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ Record pilgrims visit Baba Farid shrine | url=https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/urs-in-pakpattan-2023 | website=The News | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ Fire destroys shops in Pakpattan bazaar | url=https://www.express.pk/news/fire-pakpattan-market | website=Express Tribune | access-date=2024-11-26

- ^ a b "Pakpattan first woman deputy commissioner decided to beautify the backward city - Aaj News". YouTube. 17 September 2024.