Betawi people

Betawi wedding costume demonstrate both Middle Eastern (groom) and Chinese (bride) influences. | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c.7 million[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Native Betawi • Indonesian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Minorities | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Betawi people, Batavi, or Batavians[3][4][5] (Orang Betawi in Indonesian, meaning "people of Batavia"), are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the city of Jakarta and its immediate outskirts, as such often described as the inhabitants of the city.[6] They are the descendants of the people who inhabited Batavia (the Dutch colonial name of Jakarta) from the 17th century onwards.[7][8]

The term Betawi people emerged in the 18th century as an amalgamation of various ethnic groups into Batavia.[9][10][11]

Origin and history

[edit]

The Betawis are the most recently formed ethnic groups in Indonesia. They are a creole ethnic group in that their ancestors came from various parts of Indonesia and abroad. Before the 19th century, the self-identity of the Betawi people was not yet formed.[12] The name Betawi is adopted from the native rendering of the term "Batavia" city which was originally named after the Batavi, an ancient Germanic tribe.

In the 17th century, Dutch colonial authorities began to import servants and labours from all over the archipelago into Batavia. One of the earliest were Balinese slaves bought from Bali and Ambonese mercenaries. Subsequently, other ethnic groups followed suit; they were Malays, Sundanese, Javanese, Minangkabaus, Buginese, and Makassar. Foreign and mixed ethnic groups were also included; such as Indos, Mardijkers, Portuguese, Dutch, Arabs, Chinese, and Indians, who were originally brought to or attracted to Batavia to work.[12]

Originally, circa the 17th to 18th century, the dwellers of Batavia were identified according to their ethnics of origin; either Sundanese, Javanese, Malays, Ambonese, Buginese-Makassar, or Arabs and Chinese. This was shown in the Batavia census record that listed the immigrant's ethnic background of Batavian citizens. They were separated into specific ethnic-based enclaves kampungs, which is why in today's Jakarta there are some regions named after ethnic-specific names such as Kampung Melayu, Kampung Bali, Makassar, and Kampung Ambon. These ethnic groups merged and formed around the 18th to 19th centuries. It was not until the late 19th or early 20th century that the group – who would become the dwellers of Batavia, referred to themselves as "Betawi", which refers to a Creole Malay-speaking ethnic group that has a mixed culture of different influences; Malay, Javanese, Sundanese to Arabic and Chinese.[8] The term "Betawi" was first listed as an ethnic category in the 1930 census of Batavia residents.[12] The Betawi people have a culture and language distinct from the surrounding Sundanese and Javanese. The Betawis are known for their traditions in music and food.[13]

Language

[edit]

The Betawi language, also known as Betawi Malay, is a Malay-based creole language. It was the only Malay-based dialect spoken on the northern coast of Java; other northern Java coastal areas are overwhelmingly dominated by Javanese dialects, while some parts speak Madurese and Sundanese. The Betawi vocabulary has many Hokkien Chinese, Arabic, and Dutch loanwords. Today the Betawi language is a popular informal language in Indonesia and used as the base of Indonesian slang. It has become one of the most widely spoken languages in Indonesia, and also one of the most active local dialects in the country.[14]

Society

[edit]Due to their historical sentiment as a marginalized ethnic group in their native land, the Betawi people form several communal organizations to protect themselves from other ethnic groups and strengthen the Betawi solidarity. Notable organizations include the Forum Betawi Rempug (FBR), Forum Komunikasi Anak Betawi (Communication Forum for Betawi People, Forkabi), and Ikatan Keluarga Betawi (Betawi Family Network, IKB). These organizations act as grassroots movements to increase the bargaining power of the Betawi people whose significant part of them are economically relegated to the informal sector.[15] Some of them hold a significantly large number of followers; for example, as of 2021, Forkabi has a membership of 500,000 people across the Jabodetabek region.[16]

Religion

[edit]Religion of Betawinese[17]

A substantial majority of the Betawi people follow Sunni Islam. Anthropologist Fachry Ali of IAIN Pekalongan considers that Islam is one of the main sources for the formation of the Betawi culture and identity, and as such these two cannot be separated.[18] The element of Islam can be seen in many parts of Betawi society. For example, the Forum Betawi Rempug (FBR), a Betawi organization, considers the ethos of their organization to be the three S's: Sholat (prayer), Silat (martial arts), and Sekolah (pesantren-based education).[15] Betawi people often strongly emphasize their Islamic identity in their writings, which is observed by many foreign academics. Susan Abeyasekere of Monash University observed that many of the Betawi people are devout and orthodox Muslims.[19]

There are Betawi people who profess the Christian faith. Among the Betawi ethnic Christians, some have claimed that they are the descendants of the Portuguese Mardijker who intermarried with the local population, who mainly settled in the area of Kampung Tugu, North Jakarta. Although today Betawi culture is often perceived as Muslim culture, it also has other roots which include Christian Portuguese and Chinese Peranakan culture. Recently, there has been an ongoing debate on defining Betawi culture and identity—as mainstream Betawi organizations are criticized for only accommodating Muslim Betawi while marginalizing non-Muslim elements within Betawi culture—such as Portuguese Christian Betawi Tugu and Tangerang Buddhist Cina Benteng community.[20]

Meester Anthing became the first to bring Christianity to the Betawi community of Kampung Sawah, and founded the Protestant Church of Kampung Sawah, by combining mysticism, Betawi culture, and Christianity. However this community split into three rival factions in 1895, the first faction was led by Guru Laban based in West Kampung Sawah, the second faction was under Yoseh based in East Kampung Sawah, and the third under Guru Nathanael which was dismissed from the Protestant Church of Kampung Sawah and seek refuge in Jakarta Cathedral and adopted Catholicism.[21] The Catholic St. Servatius Church in Kampung Sawah, Bekasi, which traces its origin to the Guru Nathanael community, uses Betawi culture and language in its mass.[22] A practice that is shared by other churches in Kampung Sawah.[23]

| Religions | Total |

|---|---|

| Islam | 6,607,019 |

| Christianity | 151,429 |

| Buddhism | 39,278 |

| Hinduism | 1,161 |

| Others | 2,056 |

| Overall | 6,800,943 |

Culture

[edit]

The culture and art form of the Betawi people demonstrates the influences experienced by them throughout their history. Foreign influences are visible, such as Portuguese and Chinese influences on their music, and Sundanese, Javanese, and Chinese influences in their dances. Contrary to popular perception, which believes that Betawi culture is currently marginalized and under pressure from the more dominant neighbouring Javanese and Sundanese cultures—Betawi culture is thriving since it is being adopted by immigrants who have settled in Jakarta. The Betawi culture also has become an identity for the city, promoted through municipal government patronage. The Betawi dialect is often spoken in TV shows and dramas.[25]

Architecture

[edit]

Traditionally Betawi people are not urban dwellers living in gedong (European-style building) or two-storied Chinese rumah toko (shophouse) clustered in and around Batavia city walls. They are living in kampungs around the city filled with orchards. As Jakarta becomes more and more densely populated, so do Betawi traditional villages that have mostly now turned into a densely packed urban village with humble houses tucked in between high-rise buildings and main roads. Some of the more authentic Betawi villages survived only on the outskirts of the city, such as in Setu Babakan, Jagakarsa, South Jakarta bordering with Depok area, West Java. Traditional Betawi houses can be found in Betawi traditional kampung (villages) in Condet and Setu Babakan area, East and South Jakarta.[13]

In the coastal area in the Marunda area, North Jakarta, the Betawi traditional houses are built in rumah panggung style, which are houses built on stilts. The coastal stilt houses were built according to coastal wet environs which are sometimes flooded by tides or floods, it was possibly influenced by Malay and Bugis traditional houses. Malay and Bugis migrants around Batavia were historically clustered in coastal areas as they worked as traders or fishermen. Today, the cluster of Bugis fishermen villages can be found inhabiting Jakarta's Thousands Islands. An example of a well-preserved Betawi rumah panggung style is Rumah Si Pitung, located in Marunda, Cilincing, North Jakarta.[26]

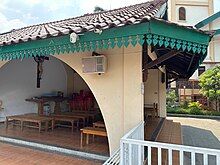

Betawi houses are typically one of three styles: rumah bapang (or rumah kebaya), rumah gudang (warehouse style), and Javanese-influenced rumah joglo. Most Betawi houses have a gabled roof, except for the joglo house, which has a high-pointed roof. Betawi architecture has a specific ornamentation called gigi balang ("grasshopper teeth") which are a row of wooden shingles applied on the roof fascia. Another distinctive characteristic of the Betawi house is a langkan, a framed open front terrace where the Betawi family receives their guests. The large front terrace is used as an outdoor living space.[13]

Music

[edit]

The Gambang kromong and Tanjidor, as well as Keroncong Kemayoran music, is derived from the kroncong music of Portuguese Mardijker people of the Tugu area, North Jakarta. "Si Jali-jali" is an example of a traditional Betawi song.

Dance and drama

[edit]

The Ondel-ondel large bamboo masked-puppet giant effigy is similar to Chinese-Balinese Barong Landung and Sundanese Badawang, the art forms of masked dance.[27] The traditional Betawi dance costumes show both Chinese and European influences, while the movements such as Yapong dance,[28] which is derived from Sundanese Jaipongan dance with a hint of Chinese style. Another dance is Topeng Betawi or Betawi mask dance.[29]

Betawi's popular folk drama is called lenong, which is a form of theater that draws themes from local urban legends, and foreign stories to the everyday life of Betawi people.[30]

Ceremonies

[edit]

Mangkeng is a ceremony used at important public gatherings and especially at weddings. The main purpose is to bring good luck and ward off the rain. It is performed by the village shaman, also called the Pangkeng shaman, where the name originates.[31]

During a Betawi wedding ceremony, there is a palang pintu (lit. door's bar) tradition of silat Betawi demonstration. It is a choreographed mock fighting between the groom's entourage with the bride's jagoan kampung (local champion). The fight is naturally won by the groom's entourage as the village champs welcome him to the bride's home.[32] The traditional wedding dress of Betawi displays Chinese influences in the bride's costume and Arabian influences in the groom's costume.[8] Betawi people borrowed the Chinese culture of firecrackers during weddings, circumcisions, or any celebrative events. The tradition of bringing roti buaya (crocodile bread) during a wedding is probably a European custom.

Other Betawi celebrations and ceremonies include sunatan or khitanan (Muslim circumcision), and the Lebaran Betawi festival.[33]

Martial arts

[edit]

Silat Betawi is a martial art of the Betawi people, which was not quite popular but recently has gained wider attention thanks to the popularity of Silat films, such as The Raid.[32] Betawi martial art was rooted in the Betawi culture of jagoan (lit. "tough guy" or "local hero") that during colonial times often went against colonial authority; despised by the Dutch as thugs and bandits, but highly respected by locals pribumis as native's champion. In the Betawi dialect, their style of pencak silat is called maen pukulan (lit. playing strike) which is related to Sundanese maen po. Notable schools among others are Beksi and Cingkrik. Beksi is one of the most commonly practised forms of silat in Greater Jakarta and is distinguishable from other Betawi silat styles by its close-distance combat style and lack of offensive leg action.[34]

Cuisine

[edit]Finding its roots in a thriving port city, Betawi has an eclectic cuisine that reflects foreign culinary traditions that have influenced the inhabitants of Jakarta for centuries. Betawi cuisine is heavily influenced by Peranakan, Malay, Sundanese, and Javanese cuisines, and to some extent Indian, Arabic, and European cuisines.[35] Betawi people have several popular dishes, such as soto betawi and soto kaki, nasi uduk, kerak telor, nasi ulam, asinan, ketoprak, rujak, semur jengkol, sayur asem, gabus pucung, and gado-gado Betawi.

-

Kue ape or kue tete

-

Roti buaya (Crocodile bread)

Notable people

[edit]

- Si Pitung, legendary bandit

- Mohammad Husni Thamrin, National Hero of Indonesia

- Benyamin Sueb, legendary comedian, singer and actor

- Imam Syafei, military figure and former special minister of security

- Ismail Marzuki, composer and musician

- Fauzi Bowo, governor of Jakarta 2007–2012

- Zainuddin M. Z., Islamic nationwide preacher and politician

- Suryadharma Ali, politician

- Omaswati, actress

- Mpok Nori, comedian

- Julia Perez, actress and singer

- Surya Saputra, actor, singer and model

- Iko Uwais, actor, martial artist and stuntman

- Ayu Ting Ting, singer

- Aiman Witjaksono, journalist and news anchor

- Asmirandah Zantman, actress and singer

- Francesca Gabriella Dewi Rezer, actress, presenter and model

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama, Dan Bahasa Sehari-Hari Penduduk Indonesia". Badan Pusat Statistik. 2010. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 24 April 2021.

- ^ Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono (2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 270 (based on 2010 census data).

- ^ Castle, Lance (1967). "The Ethnic Profile of Djakarta". Indonesia: 156.

- ^ Grijns, C. D. (1991). Jakarta Malay. Vol. 2. KITLV Press. p. 6. ISBN 9067180351.

- ^ Cribb, Robert; Kahin, Audrey (2004). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia (2 ed.). KITLV The Scarecrow Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-8108-4935-6.

- ^ Knorr, Jacqueline (2014). Creole Identity in Postcolonial Indonesia. Volume 9 of Integration and Conflict Studies. Berghahn Books. p. 91. ISBN 9781782382690.

- ^ No Money, No Honey: A study of street traders and prostitutes in Jakarta by Alison Murray. Oxford University Press, 1992. Glossary page xi

- ^ a b c Dina Indrasafitri (26 April 2012). "Betawi: Between tradition and modernity". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ^ Woelandhary, Ayoeningsih Dyah (2020). Wita, Afri (ed.). "The Betawi Society's Socio-Cultural Reflectionsin the Motif Batik Betawi". Proceeding International Conference 2020: Reposition of the Art and Cultural Heritage After Pandemic Era: 25–29.

- ^ Oktadiana, Hera; Rahmanita, Myrza; Suprina, Rina; Junyang, Pan (25 May 2022). Current Issues in Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination Research: Proceedings of the International Conference on Tourism, Gastronomy, and Tourist Destination (TGDIC 2021), Jakarta, Indonesia, 2 December 2021. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-61917-1.

- ^ Nas, Peter J. M. (13 June 2022). Jakarta Batavia: Socio-Cultural Essays. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-45429-3.

- ^ a b c "Debunking the 'native Jakartan myth'". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. 7 November 2011. Archived from the original on 5 October 2016.

- ^ a b c Indah Setiawati (24 June 2012). "Betawi house hunt". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ^ Setiono Sugiharto (21 June 2008). "The perseverance of Betawi language in Jakarta". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ^ a b Farish A. Noor. (2012). The Forum Betawi Rempug (FBR) of Jakarta: an ethnic‑cultural solidarity movement in a globalising Indonesia. (RSIS Working Paper, No. 242). Singapore: Nanyang Technological University.

- ^ Ormas Forkabi Punya Ketua Baru Artikel ini telah tayang di JPNN.com dengan judul "Ormas Forkabi Punya Ketua Baru". JPNN. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

- ^ Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono. Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015. p. 270 (based on 2010 census data).

- ^ Arti Agama Islam bagi Orang Betawi. NU Online. Retrieved March 29, 2021.

- ^ Jakarta: A History. By Susan Abeyasekere. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987.

- ^ "Betawi or not Betawi?". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. 26 August 2010.

- ^ Firdaus, Randy Ferdi (20 December 2015). "Betawi rasa Kristiani di Kampung Sawah Bekasi". merdeka.com. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Hidup Berbeda Agama Dalam Satu Atap di Kampung Sawah | Special Content

- ^ Ramadhian, Nabilla (27 December 2022). "Cerita di Balik Jemaat Misa Natal Gereja Kampung Sawah yang Pakai Baju Adat Betawi Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono. Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015. p. 273.

- ^ "What to become of native Betawi culture?". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. 26 November 2010.

- ^ "'Rumah Si Pitung' most popular among Jakarta Maritime Museum attractions". The Jakarta Post. 25 November 2017. Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- ^ "Betawi style". The Jakarta Post. 1 September 2013.

- ^ "Yapong Dance, Betawi Traditional Dance". Indonesia Tourism. 27 March 2013.

- ^ "Jakarta Traditional Dance – Betawi Mask Dance". Indonesia Travel Guide. 4 August 2015.

- ^ "Lenong". Encyclopedia of Jakarta (in Indonesian). Jakarta City Government. 13 October 2013. Archived from the original on 16 January 2013.

- ^ (in Indonesian)Wanganea, Yopie dan Abdurachman. 1985. Upacara Tradisional Yang Berkaitan Dengan Peristiwa Alam Dan Kepercayaan Daerah Khusus Ibukota Jakarta. Jakarta: Departemen Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan Proyek Inventarisasi dan Dokumentasi Kebudayaan Jakarta. Hal. 61-71.

- ^ a b Indra Budiari (13 May 2016). "Betawi 'Pencak silat' lays low among locals". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ^ Irawaty Wardany (23 August 2015). "Lebaran Betawi: An event to maintain bonds and traditions". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta.

- ^ Nathalie Abigail Budiman (1 August 2015). "Betawi pencak silat adapts to modern times". The Jakarta Post. Jakarta. Retrieved 10 August 2015.

- ^ Indah Setiawati (8 November 2013). "Weekly 5: A crash course in Betawi cuisine". The Jakarta Post. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Castles, Lance The Ethnic Profile of Jakarta, Indonesia vol. I, Ithaca: Cornell University April 1967

- Guinness, Patrick The attitudes and values of Betawi Fringe Dwellers in Djakarta, Berita Antropologi 8 (September), 1972, pp. 78–159

- Knoerr, Jacqueline Im Spannungsfeld von Traditionalität und Modernität: Die Orang Betawi und Betawi-ness in Jakarta, Zeitschrift für Ethnologie 128 (2), 2002, pp. 203–221

- Knoerr, Jacqueline Kreolität und postkoloniale Gesellschaft. Integration und Differenzierung in Jakarta, Frankfurt & New York: Campus Verlag, 2007

- Saidi, Ridwan. Profil Orang Betawi: Asal Muasal, Kebudayaan, dan Adat Istiadatnya

- Shahab, Yasmine (ed.), Betawi dalam Perspektif Kontemporer: Perkembangan, Potensi, dan Tantangannya, Jakarta: LKB, 1997

- Wijaya, Hussein (ed.), Seni Budaya Betawi. Pralokarya Penggalian Dan Pengem¬bangannya, Jakarta: PT Dunia Pustaka Jaya, 1976