Nuphar lutea

This article may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as it contains much material that is not relevant to this species, but to the genus or even the family. (June 2021) |

| Nuphar lutea | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nuphar lutea at Leiemeersen, Oostkamp, Belgium | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Order: | Nymphaeales |

| Family: | Nymphaeaceae |

| Genus: | Nuphar |

| Section: | Nuphar sect. Nuphar |

| Species: | N. lutea

|

| Binomial name | |

| Nuphar lutea | |

| |

| It is native to the region spanning from Europe to Siberia, Xinjiang, China, and North Algeria.[2] | |

| Synonyms[2] | |

|

List

| |

Nuphar lutea, the yellow water-lily, brandy-bottle, or spadderdock, is an aquatic plant of the family Nymphaeaceae, native to northern temperate and some subtropical regions of Europe, northwest Africa, and western Asia.[3][4] This species was used as a food source and in medicinal practices from prehistoric times with potential research and medical applications going forward.[5]: 30

Description

[edit]

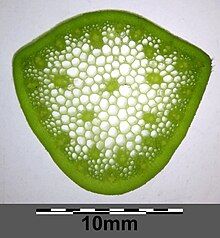

Vegetative characteristics

[edit]Nuphar lutea is an aquatic, rhizomatous,[6] perennial herb[7] with stout,[8] branching, spongy,[9] 3–8(–15) cm wide rhizomes.[10] It has floating and sumberged leaves.[11][12][10] The broadly elliptic to ovate,[9][10] green,[10] leathery floating leaf[8] with an entire margin, a deep sinus[7] and spreading basal lobes[8] is 16–30 cm long, and 11.5–22.1 cm wide.[10] The adaxial surface is glabrous, and the abaxial surface is glabrous or pubescent.[8] The trigonous petiole is 3–10 mm wide.[10] The very thin submerged leaf[7] with undulate margins has short petioles.[12]

Generative characteristics

[edit]The solitary, yellow, subglobose, 30–65 mm wide,[9] floating[12] or emergent flowers[11] have 4–10 mm wide, glabrous to pubescent peduncles.[10] The 5(–6)[9][10] yellow, broadly ovate to orbicular sepals[8] with a rounded apex[9] are 2–3 cm long.[9][8] The 11–20 obovate[9] inconspicuous petals[7] with a rounded apex are 7.5–23 mm long.[9] The androecium consists of numerous stamens[11] with 4–7 mm long, yellow anthers.[10] The sulcate, spheroidal pollen grains are 26–50 µm long.[13] The gynoecium consists of 5-20 carpels.[11] The stigmatic disk with an entire margin is 7–19 mm wide.[8] The urceolate, green, 2.6–4.5 cm long, and 1.9–3.4 cm wide fruit,[10] which is enclosed in persistent sepals,[12] bears up to 400 ovoid,[10] olive green,[10][8] 3.5–5 mm long, and 3.5 mm wide seeds.[10]

Cytology

[edit]The chromosome count is 2n = 34.[8]

Taxonomy

[edit]Publication

[edit]It was first described by Carl Linnaeus as Nymphaea lutea L. in 1753. Later, it was transferred to genus Nuphar Sm. as Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. by James Edward Smith in 1809.[2]

Species delimitation

[edit]Some botanists have treated Nuphar lutea as the sole species in Nuphar, including all the other species in it as subspecies and giving the species a holarctic range,[14][15] but the genus is now more usually divided into eight species (see Nuphar for details).[16]

Etymology

[edit]The specific epithet lutea, from the Latin luteus, means yellow.[17][18][9]

Ecology

[edit]Habitat

[edit]Habitat for Nuphar lutea ranges widely from moving to stagnant waters of "shallow lakes, ponds, swamps, river and stream margins, canals, ditches, and tidal reaches of freshwater streams"; alkaline to acidic waters; and sea level to mountainous lakes up to 10,000 feet in altitude.[5]: 24 The species is less tolerant of water pollution than water-lilies in the genus Nymphaea.[19] This aquatic plant grows in shallow water and wetlands, with its roots in the sediment and its leaves floating on the water surface; it can grow in water up to 5 metres deep.[19] It is usually found in shallower water than the white water lily, and often in beaver ponds. Since the flooded soils are deficient in oxygen, aerenchyma in the leaves and rhizome transport oxygen from the atmosphere to the rhizome roots. Often there is mass flow from the young leaves into the rhizome, and out through the older leaves.[20] This "ventilation mechanism" has become the subject of research because of this species' substantial benefit to the surrounding ecosystem by "exhaling" methane gas from lake sediments.[21]

Herbivory

[edit]Nuphar lutea plant colonies in turn are affected by organisms that graze on its leaves, gnaw on stems, and eat its roots, including turtles, birds, deer, moose, porcupines, and more. The rhizomes are often consumed by muskrats.[5]: 27–29 The waterlily leaf beetle, Galerucella nymphaeae, spends its entire life cycle around various Nuphar species, exposing leaf tissue to microbial attack and loss of floating ability.[22]

With other species in the Nymphaeales order, Nuphar lutea provides habitat for fish and a wide range of aquatic invertebrates, insects, snails, birds, turtles, crayfish, moose, deer, muskrats, porcupine, and beaver in shallow waters along lake, pond, and stream margins across the multiple continents where it is found.[23]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]Nuphar lutea is native to the region spanning from Europe to Siberia, Xinjiang, China, and North Algeria. It is extinct in Sicily, Italy. It has been introduced to Bangladesh, New Zealand, and the Russian region Primorye.[2]

Conservation status

[edit]The IUCN conservation status is Least Concern (LC).[1]

Use

[edit]Horticulture

[edit]It is cultivated as an ornamental plant.[7][24]

Food

[edit]Nuphar lutea is used as food.[25]

Symbolism

[edit]

Stylized red leaves of the yellow water lily, known as seeblatts or pompeblêden are used as a symbol of Frisia. The flag of the Dutch province of Friesland features seven pompeblêden. Stone masons carved forms of the flowers on the roof bosses of Bristol Cathedral and Westminster Abbey, these are thought to encourage celibacy.[26]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Akhani, H. 2014. Nuphar lutea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2014: e.T164316A42398895. https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2014-1.RLTS.T164316A42398895.en. Accessed on 07 June 2022.

- ^ a b c d e "Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 6 January 2024.

- ^ Flora Europaea: Nuphar lutea

- ^ "Nuphar lutea". Germplasm Resources Information Network. Agricultural Research Service, United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Padgett, Donald Jay (1997). A Biosystematic Monograph of the Genus Nuphar sm (Nymphaeaceae) (PDF) (Doctoral Dissertation). University of New Hampshire Scholars’ Repository. Retrieved December 21, 2020.

- ^ Danin, A., & Fragman-Sapir, O. (n.d.). Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. Flora of Israel and Adjacent Areas. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://flora.org.il/en/plants/NUPLUT/

- ^ a b c d e Nuphar lutea. (n.d.-b). New Zealand Plant Conservation Network. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://www.nzpcn.org.nz/flora/species/nuphar-lutea/

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Nuphar lutea (Linnaeus) Smith. (n.d.). Flora of China @ efloras.org. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from http://www.efloras.org/florataxon.aspx?flora_id=2&taxon_id=220009308

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research. (n.d.-b). Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. Flora of New Zealand. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://www.nzflora.info/factsheet/taxon/Nuphar-lutea.html

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Padgett, D. J. (2007). A Monograph of Nuphar (Nymphaeaceae). Rhodora, 109(937), 1–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23314744

- ^ a b c d Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research. (n.d.-a). Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. Biota of New Zealand. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://biotanz.landcareresearch.co.nz/scientific-names/1D1A8A4B-28B4-475A-8E85-85B287E17258

- ^ a b c d Janßen, D. (n.d.). Gelbe Teichrose Nuphar lutea (L.) Sm. Flora Emslandia - Pflanzen Im Emsland. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from http://www.flora-emslandia.de/wildblumen/nymphaeaceae/nuphar/nuphar_lutea.htm

- ^ Halbritter H., Svojtka M. 2016. Nuphar lutea. In: PalDat - A palynological database. https://www.paldat.org/pub/Nuphar_lutea/302325; accessed 2024-12-05

- ^ Beal, E. O. (1956). Taxonomic revision of the genus Nuphar Sm. of North America and Europe. Journal of the Elisha Mitchell Scientific Society 72: 317–346.

- ^ "Plants Profile: Nuphar lutea". Natural Resources Conservation Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ^ USDA Germplasm Resources Information Network: Nuphar Archived 2009-08-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Cyanella lutea subsp. lutea | PlantZAfrica. (n.d.). Retrieved January 6, 2024, from https://pza.sanbi.org/cyanella-lutea-subsp-lutea

- ^ Passiflora lutea | The Italian Collection of Maurizio Vecchia. (n.d.). Passiflora. Retrieved January 6, 2024, from https://www.passiflora.it/lutea/372/eng/

- ^ a b Blamey, M. & Grey-Wilson, C. (1989). Flora of Britain and Northern Europe. ISBN 0-340-40170-2

- ^ Dacey, J. W. H. (1981). Pressurized ventilation in the yellow water lily. Ecology, 62, 1137–47.

- ^ Dacey, J. W. H.; Klug, M. J. (March 23, 1979). "Methane Efflux from Lake Sediments Through Water Lilies". Science. 203 (4386): 1253–1255. Bibcode:1979Sci...203.1253D. doi:10.1126/science.203.4386.1253. PMID 17841139. S2CID 8478786.

- ^ Kouki, Jari (December 1991). "The Effect of the Water-lily Beetle, Garerucella nymphaeae, on Leaf Production and Leaf Longevity of the Yellow Water-lily, Nuphar lutea". Freshwater Biology. 26 (3): 347–353. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2427.1991.tb01402.x. Retrieved December 23, 2020.

- ^ "Nymphaeales". Encyclopedia of Life Sciences. John Wiley & Sons. February 26, 2003.

- ^ Nuphar lutea. (n.d.). EPPO Global Database. Retrieved December 5, 2024, from https://gd.eppo.int/taxon/NUPLU

- ^ Vanhanen, Santeri; Lagerås, Per (2020). Archaeobotanical Studies of Past Plant Cultivation in Northern Europe. Kooiweg, Holland: Barkhuis. p. 109. ISBN 9789493194113.

- ^ Reader's Digest Field Guide to the Wild Flowers of Britain. Reader's Digest. 1981. p. 29. ISBN 9780276002175.