Nu Octantis

| Observation data Epoch J2000 Equinox J2000 | |

|---|---|

| Constellation | Octans |

| Right ascension | 21h 41m 28.64977s[1] |

| Declination | −77° 23′ 24.1563″[1] |

| Apparent magnitude (V) | 3.73[2] |

| Characteristics | |

| A | |

| Evolutionary stage | Giant star |

| Spectral type | K1III[3] |

| U−B color index | +0.89[4] |

| B−V color index | +1.00[4] |

| B | |

| Evolutionary stage | Either a main sequence star or a white dwarf[5] |

| Spectral type | K7–M0V or WD[5] |

| Astrometry | |

| Radial velocity (Rv) | +34.40[6] km/s |

| Proper motion (μ) | RA: +66.41 mas/yr[1] Dec.: −239.10 mas/yr[1] |

| Parallax (π) | 45.25 ± 0.25 mas[7] |

| Distance | 72.1 ± 0.4 ly (22.1 ± 0.1 pc) |

| Absolute magnitude (MV) | 2.3±0.16[5] |

| Orbit[8] | |

| Period (P) | 1050.69+0.05 −0.07 d |

| Semi-major axis (a) | 2.62959+0.00009 −0.00011 AU |

| Eccentricity (e) | 0.23680±0.00007 |

| Inclination (i) | 70.8±0.9° |

| Longitude of the node (Ω) | 87±1.2° |

| Argument of periastron (ω) (secondary) | 74.970±0.016° |

| Semi-amplitude (K1) (primary) | 7.032±0.003 km/s |

| Details | |

| Nu Octantis A | |

| Mass | 1.61[8] M☉ |

| Radius | 5.81±0.12[8] R☉ |

| Luminosity | 17.53[2] L☉ |

| Surface gravity (log g) | 3.12±0.10[8] cgs |

| Temperature | 4,860±40[7] K |

| Metallicity [Fe/H] | +0.18±0.04[8] dex |

| Rotational velocity (v sin i) | 2.0[8] km/s |

| Age | ~2.5-3[8] Gyr |

| Nu Octantis B[5] | |

| Mass | 0.585[8] M☉ |

| Other designations | |

| Database references | |

| SIMBAD | data |

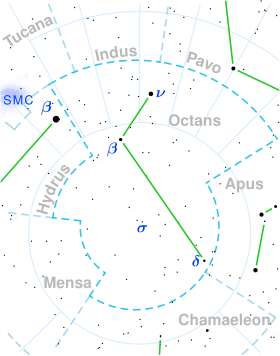

ν Octantis, Latinised as Nu Octantis, is a star in the constellation of Octans. Unusually, it is the brightest star in this faint constellation at apparent magnitude +3.7.[2] It is a spectroscopic binary[9] star with a period around 2.9 years. Parallax measurements place it at 22.1 parsecs (72 ly) from Earth.[7]

The primary has a spectral type of K1III,[3] with the luminosity class III indicating that it is a giant star that has burned up the hydrogen at its core and has expanded. Nu Octantis A has 1.6 times the mass of the Sun, but has expanded to 5.8 times the radius of the Sun.[8] Its photosphere has cooler to an effective temperature of 4,860 K[7] and now is radiating 18 times as much luminosity as the Sun.[2] It possibly hosts an extrasolar planet, a jovian planet on a retograde orbit.[5]

The secondary star is likely either a red dwarf or a white dwarf, from its relatively low mass.[5] This star is estimated to have around 60% the mass of the Sun. It shares a center of mass with the primary, completing an orbit around it every 2 years and 11 months. The orbit has an eccentricity of 0.24 and a semi-major axis of 2.63 au.[8]

Planetary system

[edit]In 2009, the system was hypothesised to contain a superjovian exoplanet based on perturbations in the orbital period.[7] A prograde solution was quickly ruled out[10] but a retrograde solution remains a possibility, although the variations may instead be due to the secondary star being itself a close binary,[11] since the formation of a planet in such a system would be difficult due to dynamic perturbations.[12] Further evidence ruling out a stellar variability and favouring the existence of the planet was gathered by 2021.[5]

| Companion (in order from star) |

Mass | Semimajor axis (AU) |

Orbital period (days) |

Eccentricity | Inclination | Radius |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | 2.1059 MJ | 1.276 | 414.8 | 0.086 | 112.5° | — |

See also

[edit]- Gamma Cephei and Nu2 Canis Majoris, another similar-sized giant stars hosting a jovian planet

- Beta Hydri

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Van Leeuwen, F. (2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. S2CID 18759600. Vizier catalog entry

- ^ a b c d Anderson, E.; Francis, Ch. (2012). "XHIP: An extended hipparcos compilation". Astronomy Letters. 38 (5): 331. arXiv:1108.4971. Bibcode:2012AstL...38..331A. doi:10.1134/S1063773712050015. S2CID 119257644. Vizier catalog entry

- ^ a b Gray, R. O.; et al. (July 2006). "Contributions to the Nearby Stars (NStars) Project: spectroscopy of stars earlier than M0 within 40 pc-The Southern Sample". The Astronomical Journal. 132 (1): 161–170. arXiv:astro-ph/0603770. Bibcode:2006AJ....132..161G. doi:10.1086/504637. S2CID 119476992.

- ^ a b Mallama, A. (2014). "Sloan Magnitudes for the Brightest Stars". The Journal of the American Association of Variable Star Observers. 42 (2): 443. Bibcode:2014JAVSO..42..443M.Vizier catalog entry

- ^ a b c d e f g Ramm, D J; Robertson, P; et al. (2021). "A photospheric and chromospheric activity analysis of the quiescent retrograde-planet host ν Octantis A". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 502 (2): 2793–2806. arXiv:2101.06844. doi:10.1093/mnras/stab078.

- ^ Wilson, R. E. (1953). "General Catalogue of Stellar Radial Velocities". Carnegie Institute Washington D.C. Publication. Carnegie Institution for Science. Bibcode:1953GCRV..C......0W. LCCN 54001336.

- ^ a b c d e Ramm, D. J.; Pourbaix, D.; Hearnshaw, J. B.; Komonjinda, S. (April 2009). "Spectroscopic orbits for K giants β Reticuli and ν Octantis: what is causing a low-amplitude radial velocity resonant perturbation in ν Oct?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 394 (3): 1695–1710. Bibcode:2009MNRAS.394.1695R. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2009.14459.x.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Ramm, D. J.; et al. (2016). "The conjectured S-type retrograde planet in ν Octantis: more evidence including four years of iodine-cell radial velocities". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 460 (4): 3706–3719. arXiv:1605.06720. Bibcode:2016MNRAS.460.3706R. doi:10.1093/mnras/stw1106.

- ^ Eggleton, P. P.; Tokovinin, A. A. (September 2008). "A catalogue of multiplicity among bright stellar systems". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 389 (2): 869–879. arXiv:0806.2878. Bibcode:2008MNRAS.389..869E. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2008.13596.x. S2CID 14878976.

- ^ Eberle, J.; Cuntz, M. (October 2010). "On the reality of the suggested planet in the ν Octantis system". The Astrophysical Journal. 721 (2): L168 – L171. Bibcode:2010ApJ...721L.168E. doi:10.1088/2041-8205/721/2/L168.

- ^ Morais, M. H. M.; Correia, A. C. M. (February 2012). "Precession due to a close binary system: an alternative explanation for ν-Octantis?". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 419 (4): 3447–3456. arXiv:1110.3176. Bibcode:2012MNRAS.419.3447M. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2966.2011.19986.x. S2CID 119152109.

- ^ Gozdziewski, K.; Slonina, M.; Migaszewski, C.; Rozenkiewicz, A. (March 2013). "Testing a hypothesis of the ν Octantis planetary system". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. 430 (1): 533–545. arXiv:1205.1341. Bibcode:2013MNRAS.430..533G. doi:10.1093/mnras/sts652.