Rolls-Royce Mustang Mk.X

| Mustang Mk.X | |

|---|---|

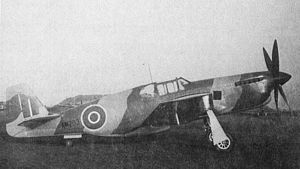

Mustang Mk.X AM203 in the third configuration tested with a high-speed paint finish applied by Sanderson and Holmes, the coachbuilders in Derby, UK. | |

| General information | |

| Type | Experimental aircraft |

| Manufacturer | North American Aviation |

| Built by | Rolls-Royce (modifications) |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force |

| Number built | 5 |

| History | |

| Introduction date | Experimental |

| First flight | 13 October 1942 |

| Developed from | North American P-51 Mustang |

The North American Mustang Mk.X,[1][2][3] also known as the "Rolls-Royce Mustang" or Mustang X, was an experimental variant of the North American Mustang I, (factory designation Model NA-73) where the Allison engine was replaced by a Rolls Royce Merlin. The improvements in performance led to the adoption of the Merlin, in the form of the licence-built Packard V-1650 version of the Merlin, in following production of the P-51 Mustang.

The Mustang, had been designed and developed by North American Aviation in 1940 to a requirement by the British Purchasing Commission for fighters to equip the Royal Air Force. However while the airframe was sound, the engine did not perform well at the high altitudes characteristic of air to air combat over Europe.[a] Rolls Royce took up a recommendation that the Mustang be tested with a Merlin engine and five aircraft were converted. The aircraft were tested by the British and then the US Army Air Forces.

It is distinct from the Merlin-powered P-51B/C that later followed.[4] The development proceeded incorporating a Rolls-Royce Merlin 65 medium-high altitude engine along with numerous modifications, in an experimental programme undertaken by Rolls-Royce in 1942.

Design and development

[edit]

The RAF had, following modifications by Lockheed at Speke to fit an oblique camera and other local British modifications, been actively using the Mustang I (Model NA-73) since early 1942 for Army Cooperation, tactical reconnaissance and as a fighter bomber and loved the aircraft's speed, range and performance.[citation needed]

In April 1942, the Royal Air Force's Air Fighting Development Unit (AFDU) tested the Allison V-1710-engined Mustang at higher altitudes and found it wanting above 18,000 ft (5,500 m). The commanding officer, Wing Commander Ian Campbell-Orde invited Ronald Harker, a test pilot from Rolls-Royce's Flight Test establishment at Hucknall to fly it.[5]

It was quickly evident that performance, although exceptional up to 15,000 ft (4,600 m), was inadequate at higher altitudes. This deficiency was due largely to the single-stage supercharged Allison engine, which lacked power at higher altitudes. Still, the Mustang's advanced aerodynamics showed to advantage, as the Mustang Mk.I was about 30 mph (48 km/h) faster than contemporary Curtiss P-40 fighters using the same Allison powerplant. The Mustang Mk.I was 30 mph (48 km/h) faster than the Supermarine Spitfire Mk Vc at 5,000 ft (1,500 m) and 35 mph (56 km/h) faster at 15,000 ft (4,600 m), despite the latter having a more powerful engine than the Mustang's Allison.[6]

Above 15,000 ft (4,600 m) however, its performance fell off quite rapidly and at 20,000 ft (6,100 m) its maximum speed was 357 mph (575 km/h), which was slower than both the Spitfire Mk V and Messerschmitt Bf 109F. Its rate of climb also decreased significantly and it required eleven minutes to reach 20,000 ft (6,100 m) versus the Spitfire Mk V at seven.[7]

Nonetheless, Harker returned from his flight so enthusiastic, that he immediately phoned Ray Dorey, Head of Rolls-Royce's Experimental Division and asked how quickly a Merlin 61[b] from the Spitfire Mk IX could be fitted to the aircraft. Within 48 hours Dorey had consulted with Ernest Hives, head of Rolls-Royce and authorisation was given to proceed.[8] Hives put forward a proposal to Air Chief Marshal Sir Wilfrid Freeman (Air Member [of the Air Council] for Production and Design) with the result that Air Ministry and Rolls Royce representatives met on 13 May.[5] By early June the Controller of Research and Development at the Ministry of Air Production had agreed to proceed with installation of Merlin 61 in a Mustang in the UK and - arranged via General Arnold - Packard were to install the Packard V-1650-1 (equivalent to a Merlin XX) in a Mustang in the US.[9]

Rolls-Royce's Chief Aerodynamic Engineer at Hucknall, Witold Challier, did aerodynamic calculations and estimated that the engine/airframe combination would result in a speed of 400 mph with the Merlin XX and with the Merlin 61 441 mph (710 km/h) at 25,600 ft (7,800 m).[10]

Rolls-Royce began the conversions of four Mustangs (RAF serials AM203, AM208, AL963 and AL975) designated Mustang Xs at Hucknall in June 1942.[7] The Ministry had specified enough aircraft that two could be provided to the USAAF.[11] The first converted, AL975, was given a Merlin 65 (instead of the high-altitude Merlin 61 suggested) and a four-bladed Rotol propeller.[7]

With a minimum of modification to the engine bay, the Merlin engine neatly fitted into the adapted engine formers. A smooth engine cowling with an additional "chin" radiator was tried out in various configurations as the two-stage Merlin required a greater cooling capacity than could be obtained with the standard Mustang radiator alone. The Merlin 65 series engine was used in all the prototypes as it was identical to the Merlin 66 powering the Spitfire Mk IX, allowing for a closer comparison. Due to the speed of the conversions, engines were often swapped from aircraft to aircraft as well as being replaced by newer units.[citation needed] The Merlin 65[12] had been installed on a new engine mounting with the intercooler for the 2-speed, 2-stage Merlin mounted under the nose.

All five development Mustang X aircraft had Merlin 65s, a medium/high altitude engine rather than the Merlin 61 high altitude engine. Visually, the Merlin Mustang differed from its Allison-engined predecessor by the removal of the latter's carburettor air intake above the nose.[13]

Testing

[edit]On 13 October 1942, AL975/G[c] was flown for the first time with a Merlin engine on 13 October 1942 by Rolls-Royce's Chief Test Pilot Ronald Shepherd. In November a maximum speed of 413 mph (665 km/h) with full supercharger and 390 mph (630 km/h) with medium supercharger was reached.[7]

The high-altitude performance was a major advance over the Mustang I, with the Mustang X serial AM208 reaching 433 mph (697 km/h) at 22,000 ft (6,700 m) full supercharger at 18 lb of boost[15] and AL975 tested at an absolute ceiling of 40,600 ft (12,400 m). Freeman ( Chief Executive at the Ministry of Aircraft Production - MAP) lobbied vociferously for Merlin-powered Mustangs, insisting two of the five experimental Mustang Mk Xs be handed over to Carl Spaatz (commander of the USAAF in Europe) for trials and evaluation by the U.S. Eighth Air Force in Britain. In this, Lt Col. Hitchcock again played a key role. After sustained lobbying at the highest level, American production started in early 1943 of a North American-designed Mustang patterned after a P-51 Mustang prototype originally designated the XP-78 that utilised the Packard V-1650-3 Merlin engine replacing the Allison engine.[16]

At the same time as the British were investigating the marriage of Merlin engine and Mustang airframe, North American Aviation were also considering the same. Under company designation NA-101, USAAF designation XP-78, they put Merlin 65s provided from the UK into two NA-91s (a cannon armed variant, known in British service as Mustang Mk IA and in USAAF as P-51) that the USAAF had kept for testing.[d] Their first XP-51B (as the XP-78 designation had been changed[17]) flew on 30 November 1942 a couple of weeks after the second Mustang X[18] The aircraft had a four blade Hamilton Standard propeller instead of the three-blade propeller used with the Allison engine. Although the testing of the conversion had been delayed, the USAAF had ordered 400 P-51Bs in August 1942 before any Merlin-engined Mustang had flown.[18]

The pairing of the P-51 airframe and Merlin engine was designated P-51B for the model NA-102 (manufactured at Inglewood, California) or P-51C for the model NA-103 (manufactured at a new plant in Dallas, Texas from summer 1943). There was no difference between these models and the RAF named both these models Mustang Mk.III. In performance tests, the P-51B achieved 441 mph (710 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,600 m), and subsequent extended range with the use of drop tanks enabled the Merlin-powered Mustang version to be introduced as a bomber escort.[citation needed]

Aircraft

[edit]

- AG518: Used for engine installation studies, but due to a lack of guns, armour and wireless equipment, it was deemed by Rolls-Royce to be "below" latest production standards and not converted.

- AM121: This aircraft arrived at the Rolls-Royce Flight Test Establishment at Hucknall on 7 June 1942 and was the first to be delivered but the last to be converted. It hd been provided to act as the baseline comparison. A broader chord fin was installed but the aircraft was not slated for testing at Hucknall and instead was sent to RAF Duxford before being loaned to the 8th Fighter Command USAAF at Bovingdon along with AL963.

- AL963: First used for performance and handling trials of the Mustang I before conversion on 2 July 1942; its nose contours had a much "sleeker" appearance due to the intercooler radiator being relocated to the main radiator duct. It was used for "stability and carburation" trials.[15] Other changes included a small fin extension and the "blanking" of cowling louvres. This example was able to reach 422 mph (679 km/h) at 22,400 ft (6,800 m). It was sent to the USAAF Air Technical Section at RAF Bovingdon for evaluation.

- AL975/G: First used for performance and handling trials of the Mustang I before conversion on 2 July 1942; flying for the first time on 13 October 1942. The aircraft was identifiable by a bulged lower engine cowling and was also fitted with a four-blade Spitfire Mk IX propeller. In testing, it achieved a top speed of 425 mph (684 km/h) at 21,000 ft (6,400 m).

- AM203: The third aircraft was fitted with a four-bladed, 11 ft 4 in diameter Rotol wooden-bladed propeller and achieved 431 mph (694 km/h) at 21,000 ft (6,400 m). It was used to test paint finishes.[15] It was loaned to the USAAF for evaluation in February 1943[15]

- AM208: The second conversion had the front radiator flap sealed permanently giving a 6–7 mph (9.7–11.3 km/h) boost. The same modification was subsequently made to all test aircraft.

Advanced developments

[edit]

In June 1943, Rolls-Royce proposed to re-engine the Mustang with a Griffon 65, although the resultant "Flying Test Bed" (F.T.B.) would involve a dramatic redesign. Three surplus Mustang I airframes were allotted by the Ministry of Aircraft Production (MAP) and were dismantled in order to provide the major components for a mid-amidships installation of the more powerful Griffon engine, somewhat like the V-1710 Allison installation in the American Bell P-39 Airacobra and Bell P-63 Kingcobra. The project culminated in a mock-up, albeit with a Merlin 61 temporarily installed, serialed as AL960, that was examined by representatives from the Ministry in 1944, but was not given priority status. Further studies involving more powerful engines or turboprops were not given approval and the development contract was cancelled in 1945 and the mock-up was destroyed.[19]

Operators

[edit]See also

[edit]Related development

- CAC Mustang

- Cavalier Mustang

- North American A-36

- North American P-51 Mustang

- North American F-82 Twin Mustang

- Piper PA-48 Enforcer

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Although it lacked performance as a fighter, the Mustang was effective at lower levels

- ^ The Merlin 61 had been developed for the high altitude Vickers Wellington B.VI bomber and then developed for the Spitfire.It used a two-stage supercharger rather than a turbosupercharger.

- ^ The 'G' appended to the serial stood for 'guard', meaning it required an armed guard at all times to maintain secrecy.[14]

- ^ The NA-101 had been ordered by the US for supply to UK under Lend Lease, 57 had been kept back by the USAAF after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and all but two of those had been converted to F-51 photo-reconnaissance aircraft.

- ^ "How the Rolls-Royce Merlin came to power the Mustang". www.key.aero. 14 July 2022. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "North American TP-51C Mustang". www.collingsfoundation.org. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "1944 North American F-51D Mustang - N3451D". www.eaa.org. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ Willis, Matthew-Mustang the untold Story-Key Books 2002

- ^ a b Delve 1999 p27

- ^ Birch 1987, p.11

- ^ a b c d Newby Grant 1981 p.22

- ^ Birch, 1987

- ^ Delve 1999 pp27-28

- ^ Delve p28

- ^ Delve p29

- ^ Birch 1987

- ^ Newby-Grant, William-P-51 Mustang. 1980 Bison Books p.22

- ^ Wagner, Ray (1990). Mustang designer: Edgar Schmued and the development of the P-51. Orion. p. 105.

- ^ a b c d Newby Grant 1981 p24

- ^ Newby-Grant, William- P-51 Mustang. 1980 p.29

- ^ Delve p32

- ^ a b Goebel, G

- ^ Birch 1987, pp. 96–98.

Bibliography

[edit]- Birch, David. Rolls-Royce and the Mustang. Derby, UK: Rolls-Royce Heritage Trust, 1987. ISBN 0-9511710-0-3.

- Delve, Ken. The Mustang Story. London: Cassell & Co., 1999. ISBN 1-85409-259-6.

- Gruenhagen, Robert W. Mustang: The Story of the P-51 Mustang. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc., 1969. ISBN 0-668-03912-4.

- Newby Grant, William (1981). P-51 Mustang. Bison Books. ISBN 0-86124-135-5.

External links

[edit]- Ronnie Harker: "The Man Who Put the Merlin in the Mustang" Retrieved: 28 July 2014.

- Rolls-Royce Merlin History and Development Retrieved: 28 July 2014.

- 2.0 The Merlin Mustangs at airvectors.net

- Rolls-Royce aircraft

- 1940s British fighter aircraft

- 1940s United States fighter aircraft

- Single-engined tractor aircraft

- Low-wing aircraft

- North American P-51 Mustang

- World War II British fighter aircraft

- Aircraft first flown in 1942

- Aircraft with retractable conventional landing gear

- Single-engined piston aircraft