Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial

| Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial | |

|---|---|

| American Battle Monuments Commission | |

| |

| For Operation Overlord | |

| Unveiled | July 19, 1956 |

| Location | 49°21′36″N 0°51′27″W / 49.3600°N 0.8575°W near Colleville-sur-Mer, France |

| Designed by | Harbeson, Hough, Livingston & Larson Markley Stevenson (landscaping) Donald De Lue (sculptor) Leon Kroll (murals) Robert Foster (maps) |

| Total burials | 9,388 |

Unknowns | 307 |

| Commemorated | 1,557 |

| Burials by nation | |

* United States: 9,388 | |

| Burials by war | |

* World War II: 9,387

| |

| Statistics source: American Battle Monuments Commission | |

The Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial (French: Cimetière américain de Colleville-sur-Mer) is a World War II cemetery and memorial in Colleville-sur-Mer, Normandy, France, that honors American troops who died in Europe during World War II. It is located on the site of the former temporary battlefield cemetery of Saint Laurent, covers 172.5 acres and contains 9,388 gravesites.[1]

A memorial in the cemetery includes maps and details of the Normandy landings and military operations that followed. At the memorial's center is Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves, a bronze statue. The cemetery also includes two flag poles where, at different times, people gather to watch the American flags being lowered and folded.

The cemetery, which was dedicated in 1956, is the most visited cemetery of those maintained by the American Battle Monuments Commission (ABMC), with one million visitors a year. In 2007, the ABMC opened a visitor center at the cemetery, relating the global significance and meaning of Operation Overlord.[2]

History

[edit]

On June 6, 1944, the 607th Quartermaster Graves Registration Company of the U.S. First Army established the temporary cemetery, the first American cemetery on French soil in World War II.[3] After the war, the present-day cemetery was established a short distance to the east of the original site.

It was dedicated on July 19, 1956, in the presence of Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid of the U.S. Navy, representing President Dwight D. Eisenhower, and French General Jean Ganeval, representing President René Coty.

Like all other overseas American cemeteries in France for World War I and II, the French Government has granted the United States a special concession to the land occupied by the cemetery, for an unlimited duration, free of any charge or any tax, as long as the United States maintains the cemetery. It does not benefit from extraterritoriality and remains the property of the French State.[4] This cemetery is managed by the American Battle Monuments Commission, a small independent agency of the U.S. federal government, under Congressional acts that provide yearly financial support for maintaining them, with most military and civil personnel employed abroad. The U.S. flag flies over these granted soils.[3]

Description

[edit]

The cemetery is located on a bluff overlooking Omaha Beach (one of the landing beaches of the Normandy Invasion) and the English Channel. It covers 172.5 acres, and contains the remains of 9,388 American military dead, most of whom were killed during the invasion of Normandy and ensuing military operations in World War II. Included are graves of Army Air Corps crews shot down over France as early as 1942 and four American women.[5]

Only some of the soldiers who died overseas are buried in the overseas American military cemeteries. When it came time for a permanent burial, the next of kin eligible to make decisions were asked if they wanted their loved ones repatriated for permanent burial in the United States or interred at the closest overseas cemetery.

Burials

[edit]Number of burials

[edit]On June 19, 2018, Julius H.O. Pieper was laid to rest next to his twin brother, Ludwig J.W. Pieper, and became the 9,388th servicemember buried at the Normandy American Cemetery.[6]

These burials are marked by white Lasa marble headstones, 9,238 of which are Latin crosses (for Protestants and Catholics) and 151 of which are stars of David (for Jews). Since these were the only three religions recognized at the time by the United States Army, no other type of markers are present.[1]

The cemetery contains the graves of 45 pairs of brothers (30 of which buried side by side), a father and his son, an uncle and his nephew, 2 pairs of cousins, 3 generals, 4 chaplains, 4 civilians, 4 women, 147 African Americans and 20 Native Americans.

304 unknown soldiers are buried among the other service members. Their headstones read "HERE RESTS IN HONORED GLORY A COMRADE IN ARMS KNOWN BUT TO GOD".

East of the Memorial lies the Wall of the Missing, where are inscribed the names of 1,557 servicemembers declared missing in action during Operation Overlord. Nineteen of these names bear a bronze rosette, meaning that their body was found and identified since the cemetery's dedication.[1]

Notable interments

[edit]

Among the burials at the cemetery are three recipients of the Medal of Honor, including Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of President Theodore Roosevelt. After the creation of the cemetery, another son of President Roosevelt, Quentin, who had been killed in World War I, was exhumed and reburied next to his brother.

Notable burials at the cemetery include:

- Joseph M. Jordan, Benjamin J. Stoney, Robert J. Bloser, Everett J. Gray, and Terrance C. Harris, members of E Company, 506th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne

- Lesley J. McNair, U.S. Army general, one of the two highest-ranking Americans to be killed in action in World War II

- Two of the Niland brothers, Preston and Robert, whose story inspired Steven Spielberg's Saving Private Ryan[7]

- Jimmie W. Monteith, Medal of Honor recipient

- Frank D. Peregory, Medal of Honor recipient[8]

- Quentin Roosevelt, son of President Theodore Roosevelt, aviator killed in action in World War I and reburied next to the grave of his brother, Theodore Roosevelt Jr.

- Theodore Roosevelt Jr., son of President Theodore Roosevelt, Medal of Honor recipient

Layout

[edit]

The Cemetery is divided into ten plots. It forms a Latin cross, with the Chapel in its middle, and the Memorial and Wall of the Missing at its base.

It faces the United States, in the direction of a point between Eastport and Lubec, Maine. This is coincidental, as the Cemetery was built parallel to the beach on the lands granted by the French.

Memorial

[edit]The Memorial consists of a semicircular colonnade with a loggia at each end containing maps and narratives of the military operations. It is built in medium-hard limestone from upper Burgundy. Two of the maps, designed by Robert Foster, are 32 feet long and 20 feet high.

At the center is a 22-foot bronze statue entitled The Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves by Donald De Lue.

Over the arches of the Memorial is engraved "THIS EMBATTLED SHORE, PORTAL OF FREEDOM, IS FOREVER HALLOWED BY THE IDEALS, THE VALOR AND THE SACRIFICES OF OUR FELLOW COUNTRYMEN".

At the feet of the Memorial is engraved both in English and French "IN PROUD REMEMBRANCE OF THE ACHIEVEMENTS OF HER SONS AND IN HUMBLE TRIBUTE TO THEIR SACRIFICES THIS MEMORIAL HAS BEEN ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA".

-

The Memorial from the other side of the reflecting pool

-

Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves

-

Spirit of American Youth Rising from the Waves

-

Map of the landings on the Normandy beaches

-

Map of the air operations over Normandy

-

Map of the amphibious assault landings

-

Map of the military operations in Western Europe

Wall of the Missing

[edit]The semi-circular gardens bear the 1,557 engraved names of service members declared missing in action in Normandy. Most of them were lost at sea, including over 489 in the sinking of the SS Léopoldville.

Nineteen of these names bear a bronze rosette next to their name, meaning that their body was recovered and identified after the cemetery's dedication.

Above the walls is engraved, both in English and French,

★ COMRADES IN ARMS WHOSE RESTING PLACE IS KNOWN ONLY TO GOD ★

★ HERE ARE RECORDED THE NAMES OF AMERICANS WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE SERVICE OF THEIR COUNTRY AND WHO SLEEP IN UNKNOWN GRAVES ★ THIS IS THEIR MEMORIAL ♦ THE WHOLE EARTH THEIR SEPULCHER ★

At its center is engraved "TO THESE WE OWE THE HIGH RESOLVE THAT THE CAUSE FOR WHICH THEY DIED SHALL LIVE", an abbreviation of General Dwight D. Eisenhower's dedication of the Golden Book in St Paul's Cathedral, London.

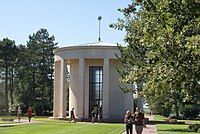

Chapel

[edit]At the center of the cemetery lies a multi-confessional chapel. Its altar, in black and gold Pyrenean marble, reads “I GIVE UNTO THEM ETERNAL LIFE AND THEY SHALL NEVER PERISH”. The stained glass behind it bears a Latin cross and present a star of David, as well as an alpha and an omega symbol, meant to represent all other religions.

On its ceiling lies a spectacular mosaic by Leon Kroll. Completed in 1953, it comprises 500,000 tiles and tells a full round story “of war and peace.” One side depicts Columbia (Goddess of Liberty) allegorically representing America blessing “her rifle-bearing son before he departs to fight overseas. Above him, a warship and a bomber push through sea and air toward land on the opposite side of the dome. There, a red-capped Marianne figure personifying France bestows a laurel wreath upon the same young man. His now lifeless body leans against her as she cradles his head in her lap. Above them, the return of peace is illustrated with an angel, a dove and a homeward-bound troop ship.” [9] These two figures can be seen again as statues, guarding the end of the cemetery.[10]

Outside is engraved on its wall, both in English and French

THIS CHAPEL HAS BEEN ERECTED BY THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA IN GRATEFUL MEMORY OF HER SONS WHO GAVE THEIR LIVES IN THE LANDINGS ON THE NORMANDY BEACHES AND THE LIBERATION OF NORTHERN FRANCE ★ THEIR GRAVES ARE THE PERMANENT AND VISIBLE SYMBOL OF THEIR HEROIC DEVOTION AND THEIR SACRIFICE IN THE COMMON CAUSE OF HUMANITY

On its roof is engraved

THESE ENDURED ALL AND GAVE ALL THAT JUSTICE AMONG NATIONS MIGHT PREVAIL AND THAT MANKIND MIGHT ENJOY FREEDOM AND INHERIT PEACE

-

The Chapel at the cemetery

-

View from the memorial in 1989

-

Altar inside the Chapel

-

Ceiling of the Chapel

Orientation Table

[edit]An orientation table overlooks the beach and depicts the landings at Normandy. Designed by Robert Foster, it is of Swedish black granite.

-

Orientation Table

-

Now closed access to Omaha Beach from the cemetery

Time capsule

[edit]

Embedded in the lawn directly opposite the entrance to the old Visitors' Building is a time capsule which has been sealed and contains news reports of the June 6, 1944, Normandy landings. The capsule is covered by a pink granite slab upon which is engraved: To be opened June 6, 2044. Affixed in the center of the slab is a bronze plaque adorned with the five stars of a General of the Army and engraved with the following inscription: "In memory of General Dwight D. Eisenhower and the forces under his command. This sealed capsule containing news reports of the June 6, 1944, Normandy landings is placed here by the newsmen who were there, June 6, 1969."[11]

Landscaping

[edit]The cemetery is planted with Austrian black pines, holly oaks, and Turkey oaks. Its undergrowth is composed of Austrian pines, alders, common oak trees, American red oak trees, holly oak trees, ash trees, sycamore trees, maple trees, and a few maritime pines and pine trees. It is decorated by polyantha roses, common heather and Erica heather.

Sights

[edit]

- Notre-Dame de l'Assomption de Colleville in Colleville-sur-Mer: dated to the 12th or 13th century, a historical monument since 1840.

- Overlord Museum is located in Colleville-sur-Mer on the road to Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial.

In popular culture

[edit]- In Saving Private Ryan (1998), the cemetery is featured at the beginning and end, showing World War II veteran Private James Francis Ryan accompanied by his family. In the beginning of the film, he makes his way to the grave of Captain John Miller (played by Tom Hanks). At the end, Ryan, who was instructed by Miller to earn the sacrifices made to send him home, says that he lived his life as best as he could and hopes that he has earned all that Miller and his men did for him. After asking for confirmation from his wife that he lived a good life and was a good man, Ryan salutes the grave (both the grave and Captain John Miller are fictional; the headstone for Miller was only brought to the cemetery for the movie). The Private Ryan story is based upon the story of the Niland Brothers, two of whom are buried in the cemetery; references are also made to the five Sullivan brothers, who were all killed in the "Juneau incident".

- Symphonic Prelude (The Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer), by Mark Camphouse, portrays the battle in a way that battles are commonly depicted for bands: a slow introduction followed by a moderate tempo body and a majestic ending.

- The cemetery is featured on the album cover of the 1977 Scorpions album Taken by Force.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c American Battle Monuments Commission. "Normandy American Cemetery". abmc.gov. American Battle Monuments Commission. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "New Normandy American Cemetery Visitor Center Opens". American Battle Monuments Commission. June 6, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ a b Source:American Battle Monument Commission Archived November 26, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Agreement Concerning the Interment in France and in Territories of the French Union or the Removal to the United States of the Bodies of American Soldiers Killed in the War of 1939-1945 Archived 2024-06-01 at the Wayback Machine, signed in Paris on October 1, 1947, Treaties and Other International Acts Series 1720.

- ^ "Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial". tracesofwar.com. Archived from the original on February 22, 2019. Retrieved February 21, 2019.

- ^ American Battle Monuments Commission (June 13, 2018). "Sailor Accounted for from World War II to be Buried Next to Twin Brother with Full Military Honors at Normandy American Cemetery, France". abmc.gov. American Battle Monuments Commission. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ "The Niland Boys | Andrew L. Bouwhuis Library". library.canisius.edu. Archived from the original on 2019-04-12. Retrieved 2019-04-12.

- ^ Sterner, Doug. "MOH Citation for Frank Peregory". Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2006.

- ^ McBride, Bunny (June 5, 2019). "Of Bombs and Beaches: Leon Kroll's Mosaic Ceiling at Omaha Beach". France-Amérique. Archived from the original on June 7, 2024. Retrieved March 4, 2020.

- ^ "New Normandy American Cemetery Visitor Center Opens - American Battle Monuments Commission". www.abmc.gov. June 6, 2007. Archived from the original on October 12, 2018. Retrieved September 24, 2018.

- ^ "Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial" (PDF). The American Battle Monuments Commission. 2002. pp. 17–18. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 26, 2011. Date of publication is inferred from citation of Fiscal Year 2002 visitor numbers.

Further reading

[edit]- Sledge, Michael (2005). Soldier Dead: How We Recover, Identify, Bury, and Honor Our Military Fallen. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231509374. OCLC 60527603.

External links

[edit]- Complete List of Memorial Events for 65th Anniversary of D-Day

- American D-Day: Omaha Beach, Utah Beach & Pointe du Hoc

- World War II Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial, American Battle Monuments Commission

- Organization Les Fleurs de la Mémoire

- World War I cemeteries.com a comprehensive guide to the military cemeteries and memorials around the world

- "Overview by name, American Cemetery and Memorial"

- "Names of the people buried in the cemetery"

- "Overview of the graves on the American Cemetery and Memorial Normandy by State

- "Numbers by unit (example first row: 463 graves of the 262 Infantry Regiment of the 66 Division)."

- Normandy American Cemetery and Memorial at Find a Grave