Nodocephalosaurus

| Nodocephalosaurus Temporal range: Late Cretaceous,

| |

|---|---|

| |

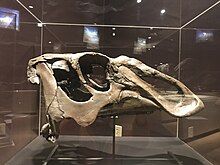

| Nodocephalosaurus holotype SMP VP-900 (right) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | †Ornithischia |

| Clade: | †Thyreophora |

| Clade: | †Ankylosauria |

| Family: | †Ankylosauridae |

| Subfamily: | †Ankylosaurinae |

| Tribe: | †Ankylosaurini |

| Genus: | †Nodocephalosaurus Sullivan, 1999 |

| Type species | |

| †Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis Sullivan, 1999

| |

Nodocephalosaurus (meaning "knob headed lizard") is a monospecific genus of ankylosaurid dinosaur from New Mexico that lived during the Late Cretaceous (late Campanian to early Maastrichtian stage, 73.49 to 73.04 Ma) in what is now the De-na-zin member of the Kirtland Formation.[1][2] The type and only species, Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis, is known only from a partial skull.[1] It was named in 1999 by Robert M. Sullivan.[1] Nodocephalosaurus has an estimated length of 4.5 metres (15 feet) and weight of 1.5 tonnes (3,306 lbs).[3] It is closely related and shares similar cranial anatomy to Akainacephalus.[2]

Discovery and naming

[edit]

In 1995, a partial skull of an ankylosaur was discovered weathering out of a grey mudstone a few hundred metres west of a new Parasaurolophus site in the De-na-zin member of the Kirtland Formation, New Mexico. Robert M. Sullivan and Thomas E. Williamson left the partial skull in the field due to the apparent fragmentary nature of the skull and time constraints. A year later, the skull was obtained from the site by Sullivan with the help of Kesler Randall. The specimen was subsequently described in 1999 by Robert M. Sullivan. The holotype specimen, SMP VP-900 , consists of an incomplete skull and associated cranial fragments. The holotype specimen is currently housed at the State Museum of Pennsylvania, Harrisburg.[1]

The generic name, Nodocepahlosaurus, is derived from the Latin word "nodus" (knob or swelling ) and the Greek words "kephale" (head) and "sauros" (lizard), in reference to the many bulbous osteoderms fused to the top of the skull. The specific name, kirtlandensis, refers to the Kirtland Formation, the formation from which the holotype came.[1]

In 2000, Tracy Ford assigned NMMNH P-20880, a single pup-tent scute with a hollowed-out base, as a potential specimen of Nodocephalosaurus.[4] In 2006, Robert M. Sullivan and Denver W. Fowler referred four additional specimens: SMPVP-1957, two cranial osteoderms; SMP VP-1870, a left cervical spine; SMP VP-1149, the seventh or eighth caudal vertebrae; and SMP VP-1743, the first caudal vertebra.[5] The specimens were referred to Nodocephalosaurus as, at the time, it was the only named ankylosaurid from the Kirtland Formation.[5] In 2011, Michael Burns and Robert M. Sullivan referred three more additional specimens: SMP VP-1632, an incomplete minor tail club plate; SMP VP- 1646, an incomplete tail club that consists of an incomplete major plate and minor plate; and SMP VP2074, a nearly complete left plate, partial right plate and numerous miscellaneous tail club fragments.[6] These three additional specimens were referred to the genus based on the similar surface texture to the holotype specimen.[6] However, Arbour & Currie (2015) assigned all referred specimens, with the exception of SMPVP-1957, to Ankylosauridae indet. due to the discovery of Ahshislepelta in the Hunter Wash Member, and Ziapelta from the De-na-zin Member.[7]

Description

[edit]Size and distinguishing traits

[edit]In 2016, Gregory S. Paul gave Nodocephalosaurus an estimated length of 4.5 metres (15 feet) and a weight of 1.5 tonnes (3,306 lbs).[3]

Sullivan (1999) originally diagnosed Nodocephalosaurus based on the presence of semi-inflated to bulbous polygonal osteoderms fused to the nasal, frontal and supraorbital regions of the skull, a prominent quadratojugal horn that is directed anteroventrally, and a prominent post-maxillary/lacrimal osteoderm.[1] However, Arbour & Currie (2015) later diagnosed Nodocephalosaurus based on the presence of a bulbous, ridge-like loreal caputegulum, a quadratojugal horn with an anteriorly positioned apex, conical frontonasal caputegulae with circular bases, lacks V-shaped upraised area of frontals, and a lacrimal caputegulum that is smaller, more square than in Ankylosaurus, Anodontosaurus, Euoplocephalus.[7]

Cranium

[edit]

The skull of Nodocephalosaurus is incomplete, partially crushed and consists mostly of the left half. The skull has an estimated length of 39 cm from the left nasal to the rear of the skull. The snout is directed anteroventrally and the skull is highly arched in profile. The skull is fractured with most of the breaks occurring along cranial sutures and the premaxilla is not preserved. Numerous disarticulated fragments that are presumably from the right side were recovered. The basicranium is deformed on the dorsal region due to post-mortem crushing and cementation of cranial elements, while the ventral region is better preserved. The basioccipital and basisphenoid are partially fused and are compressed towards the left side of the skull. The right exoccipital is not preserved, while the left exoccipital is lodged between the left side of the squamosal region, skull roof, basioccipital, and basisphenoid. The occipital condyle is large, ovoid in shape, and both portions of the condyle are fused. The supraoccipital cannot be distinguished as it is presumably part of a large mass of bone that lies between the skull roof and the occipital condyle. The parasphenoid is obscured by a parasagittal bony mass that represents part of the skull roof and associated osteoderms of the frontal region. Due to the overlying osteoderms that are fused to the skull roof, the frontals are not visible in dorsal view. The jugal has a smooth inner surface that differs from the rugose outer surface, which is a characteristic of osteodermal sculpturing. The lacrimal is mostly obscured by osteoderms and rises up within the inner lateral orbital region. The maxilla, in left lateral aspect, forms a distinct arc. The end of the maxilla ends in a "foot" that has a flattened ovoid surface. Both above and behind the "foot" lies an irregular sub-ovoid osteoderm. An ascending maxillary process forms the internal wall of the external naris. The maxilla preserves only 19 alveoli, although no teeth are preserved. The posterior extent of the nasal cannot be described precisely due to the osteodermal covering. The anterior part has large dermal ossifications and covers most of the nasal. A separate dermal ossification is visible on the left lateral side of the posterior part. The left nasal terminates in a "foot" that tapers ventrally to a V-shape. The palatine is bordered medially by the vomer and behind the palatine lies a matrix-filled area that corresponds to the palatal foramen of Pinacosaurus. The right palatine has a ventral surface that is lightly pitted, with a rugose texture on the posteromedial part. The upper side of the parietals are covered with a thin osteodermal covering and a large plate-like osteoderm occupies the front part of the parietal table which contacts the posterior-most lateral frontal osteoderm.[1]

A rugose osteoderm is present in the posterior region of the parietals where the squamosal horn attaches to the end dorsolateral side of the skull. Both pterygoids are incomplete and a fracture occurs near the front where the pterygoids join the basicranium. The front half of the anterior wings of the left pterygoid is partly preserved, while the front half of the anterior wings of the left pterygoid is missing. The quadrate is incomplete and has a distinct ridge along the front surface. The quadratojugal bears an osteodermal covering on its side projecting end. The upper surface of the quadratojugal has an upper surface that is broad and relatively smooth in lateral view, with some irregular pitting. The lower portion of the anterodorsal-most part of the quadratojugal has a sub-triangular shape. The osteodermal covering of the medial side is confined to the lower edge of the horn. Foramina are present and are irregularly spaced along the upper part of the osteodermal covering. Sullivan (1999) originally reconstructed the quadratojugal horn as pointing ventrally.[1] However, Arbour & Currie (2015) suggested a new interpretation where the quadratojugal horn is rotated clockwise, nearly completes the ventral border of the orbit, but results in a gap between the quadratojugal and squamosal.[7] The squamosal bone is covered in an osteodermal covering and can only be inferred. The squamosal horn is broken off at its base from the squamosal region of the skull. Due to the distortion of the posterior part of the skull, the articulation of the squamosal horn is uncertain. The squamosal horns arches towards the back, terminating in a rounded point. The underside surface of the horn is broader than the dorsal surface and is sub-triangular in cross section, which is somewhat laterally compared to that of Scolosaurus or Oohkotokia. The supraorbitals are covered in osteoderms that lie dorsoanteriorly to the orbit as seen in Pinacosaurus. The osteoderms of the external surface are characterised by the presence of rugose ornamentation consisting of pits and poorly defined ridges.[1]

The osteoderms of the cranium are similar to those seen on Saichania and Tarchia in their arrangement and morphology. The skull roof preserves frontonasal osteoderms. Two rows of osteoderms extend across the left frontal, although the lateral row is not well defined. Small, sub-inflated osteoderms are present near the region of the frontoparietal contact. A small saddle with a small, raised osteoderm lies at the upper region between the supraorbital osteoderms. In front of the saddle lies a polygonal osteoderm that has a low, raised central apex. The frontal series consists of four well-defined osteoderms at the medial edge. The upper part of the frontoparietal contact lies a polygonal plate-like osteoderm. In front of the osteoderm is another but with a slightly raised centre. The upper region of the parasagittal plane preserves a small, conical osteoderm. Behind the osteoderm are a set of incomplete osteoderms that may represent a part of the right side of the skull. As in other ankylosaurids, the region corresponding to the parietal table of the skull consists of a low-relief osteodermal covering.[1] Nodocephalosaurus shares similar anatomical features with Akainacephalus, such as the lateral orientation of the external nares and the morphology of the supranarial, loreal and frontal caputegulae.[2] Numerous cranial osteoderms possibly referable to the right side of the skull were recovered which vary in size and shape. The largest osteoderm probably represents the posterior-most parasagittal osteoderm and is highly inflated with a sub-square base outline.[1]

Classification

[edit]Sullivan (1999) originally considered Nodocephalosaurus to be closely related to Saichania and Tarchia, although this was not based on the result of a phylogenetic analysis but rather the presence of bulbous caputegulae on the skull.[1] However, Vickaryous et al. (2004) interpreted it as Ankylosauridae incertae sedis.[8] Thompson et al. (2012) found Nodocephalosaurus to be sister taxon to a clade containing Talarurus, Tianzhenosaurus, Tarchia and Saichania,[9] while Arbour & Currie (2015) found it to be sister taxon to Talarurus,[7] a position also recovered by Arbour & Evans (2017),[10] Zheng et al. (2018),[11] and Rivera-Sylva et al. (2018).[12]

The results of an analysis by Arbour & Currie (2015) are reproduced below.[7]

Wiersma and Irmis (2018) found Nodocephalosaurus to be within a southern Laramidian clade containing Akainacephalus that is nested within Asian taxa rather than other Laramidian taxa and suggested that this clade was a separate biogeographic dispersal event from Asia independent from the main radiation of Laramidian ankylosaurids.[2] A phylogenetic analysis conducted by Wiersma and Irmis (2018) is reproduced below.[2]

Describing a new ankylosaurine ankylosaurid Datai in 2024, Xing et al. recovered Nodocephalosaurus as a sister taxon to Talarurus when Zheng et al. (2018) dataset after the deletion of 14 taxa is used.[13]

Paleoenvironment

[edit]

Nodocephalosaurus is known from the De-na-zin member of the Kirtland Formation which has been dated to the upper-most Campanian to lower-most Maastrichtian stage, 73.49 ± 0.25 to 73.04 ± 0.25 Ma, and may be a taxon unique to the Willow Wash local fauna.[1][2] The Kirtland Formation consists of interbedded sandstone, siltstone, mudstone, coal and shale.[14] The Kirtland Formation lies on the western margin of the Western Interior Seaway and represents a floodplain that was abundant with ferns, conifers and flowering plants.[15] Based on the abundance of angiosperms with leaves that have entire or nearly entire margins and drip points, the Kirtland Formation may have had a warm temperate to subtropical climate.[15] The Kirtland Formation was better drained than the underlying Fruitland Formation due to the lack of coal swamps.[15] The presence of Nodocephalosaurus and other ankylosaurids suggests that there was a higher diversity of ankylosaurids in the San Juan Basin than that of nodosaurids.[16]

Nodocepahlosaurus coexisted with the saurolophine hadrosaurids Anasazisaurus,[17] Kritosaurus[18] and Naashoibitosaurus,[17] the lambeosaurine hadrosaurid Parasaurolophus,[19] the chasmosaurine ceratopsid Pentaceratops,[20] the pachycephalosaurid Sphaerotholus,[21] the ankylosaurine ankylosaurid Ziapelta,[16] the dromaeosaurid Saurornitholestes,[22] and an indeterminate ornithomimid.[23] Non-dinosaur taxa contemporaneous with Nodocephalosaurus include an indeterminate choristodere,[14] the crocodylomorphs Denazinosuchus,[24] Brachychampsa[14] and Leidyosuchus,[14] the turtles Basilemys,[14] Denazinemys,[14] Neurankylus,[14] Plastomenus[14] and Thescelus,[14] and the fishes Melvius[14] and Myledaphus.[14]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Sullivan, R. (1999). "Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis, gen et sp nov., a new ankylosaurid dinosaur (Ornithischia; Ankylosauria) from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (Upper Campanian), San Juan Basin, New Mexico". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 19 (1): 126–139. Bibcode:1999JVPal..19..126S. doi:10.1080/02724634.1999.10011128.

- ^ a b c d e f Wiersma, J.P.; Irmis, R.B. (2018). "A new southern Laramidian ankylosaurid, Akainacephalus johnsoni gen. et sp. nov., from the upper Campanian Kaiparowits Formation of southern Utah, USA". PeerJ. 6: e5016. doi:10.7717/peerj.5016. PMC 6063217. PMID 30065856.

- ^ a b Paul, G.S., 2016, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs 2nd Edition, Princeton University Press

- ^ T.L. Ford. (2000). "A review of ankylosaur osteoderms from New Mexico and a preliminary review of ankylosaur armor", In: S. G. Lucas and A. B. Heckert (eds.), Dinosaurs of New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 17: 157-176

- ^ a b M. Sullivan, Robert; W. Fowler, Denver (2006). "New specimens of the rare ankylosaurid dinosaur Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis (Ornithischia: Ankylosauridae) from the Upper Cretaceous Kirtland Formation (De-na-zin Member), San Juan Basin, New Mexico". In G. Lucas, Spencer; M. Sullivan, Sullivan (eds.). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior: Bulletin 35. pp. 259–262. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b E. Burns, Michael; M. Sullivan, Robert (2011). "The tail club of Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis (Dinosauria: Ankylosauridae), with a review of ankylosaurid tail club morphology and homology". In M. Sullivam, Robert; G. Lucas, Spencer; A. Spielmann, Justin (eds.). Fossil Record 3: Bulletin 53. pp. 179–186. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Arbour, V. M.; Currie, P. J. (2015). "Systematics, phylogeny and palaeobiogeography of the ankylosaurid dinosaurs". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 14 (5): 1–60. Bibcode:2016JSPal..14..385A. doi:10.1080/14772019.2015.1059985. S2CID 214625754.

- ^ Weishampel, D.B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H., eds. (2004). "Chapter 17: Ankylosauria". The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 9780520941434.

- ^ Richard S. Thompson, Jolyon C. Parish, Susannah C. R. Maidment and Paul M. Barrett, 2012, "Phylogeny of the ankylosaurian dinosaurs (Ornithischia: Thyreophora)", Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(2): 301–312

- ^ Arbour, Victoria M.; Evans, David C. (2017). "A new ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Judith River Formation of Montana, USA, based on an exceptional skeleton with soft tissue preservation". Royal Society Open Science. 4 (5): 161086. Bibcode:2017RSOS....461086A. doi:10.1098/rsos.161086. PMC 5451805. PMID 28573004.

- ^ Wenjie Zheng; Xingsheng Jin; Yoichi Azuma; Qiongying Wang; Kazunori Miyata; Xing Xu (2018). "The most basal ankylosaurine dinosaur from the Albian–Cenomanian of China, with implications for the evolution of the tail club". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): Article number 3711. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.3711Z. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21924-7. PMC 5829254. PMID 29487376.

- ^ Rivera-Sylva, H.E.; Frey, E.; Stinnesbeck, W.; Carbot-Chanona, G.; Sanchez-Uribe, I.E.; Guzmán-Gutiérrez, J.R. (2018). "Paleodiversity of Late Cretaceous Ankylosauria from Mexico and their phylogenetic significance". Swiss Journal of Palaeontology. 137 (1): 83–93. Bibcode:2018SwJP..137...83R. doi:10.1007/s13358-018-0153-1. ISSN 1664-2376. S2CID 134924657.

- ^ Xing, Lida; Niu, Kecheng; Mallon, Jordan; Miyashita, Tetsuto (2023). "A new armored dinosaur with double cheek horns from the early Late Cretaceous of southeastern China". Vertebrate Anatomy Morphology Palaeontology. 11. doi:10.18435/vamp29396. ISSN 2292-1389.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k M. Sullivan, Robert; G. Lucas, Spencer (2006). "The Kirtlandian land-vertebrate "age"-faunal composition, temporal position and biostratigraphic correlation in the nonmarine Upper Cretaceous of western North America". In G. Lucas, Spencer; M. Sullivan, Sullivan (eds.). Late Cretaceous Vertebrates from the Western Interior: Bulletin 35. pp. 7–30. Retrieved 19 January 2022.

- ^ a b c R. Robison, Coleman; Hunt, Adrian; L. Wolberg, Donald (1982). "New Late Cretaceous leaf locality from lower Kirtland Shale member, Bisti area, San Juan Basin, New Mexico" (PDF). New Mexico Geology. 4 (3): 42–45. doi:10.58799/NMG-v4n3.42.

- ^ a b Arbour, Victoria M.; Burns, Michael E.; Sullivan, Robert M.; Lucas, Spencer G.; Cantrell, Amanda K.; Fry, Joshua; Suazo, Thomas L. (24 September 2014). "A New Ankylosaurid Dinosaur from the Upper Cretaceous (Kirtlandian) of New Mexico with Implications for Ankylosaurid Diversity in the Upper Cretaceous of Western North America". PLOS ONE. 9 (9). PLOS: e108804. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...9j8804A. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0108804. PMC 4177562. PMID 25250819.

- ^ a b Hunt, Adrian P.; Lucas, Spencer G. (1993). "Cretaceous vertebrates of New Mexico". In Lucas, S.G.; Zidek, J. (eds.). Dinosaurs of New Mexico. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 2. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 77–91.

- ^ Prieto-Márquez, A. (2013). "Skeletal morphology of Kritosaurus navajovius (Dinosauria:Hadrosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of the North American south-west, with an evaluation of the phylogenetic systematics and biogeography of Kritosaurini". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 12 (2): 133–175. Bibcode:2014JSPal..12..133P. doi:10.1080/14772019.2013.770417. S2CID 84942579.

- ^ Sullivan, R.S.; Williamson, T.E. (1999). "A new skull of Parasaurolophus (Dinosauria: Hadrosauridae) from the Kirtland Formation of New Mexico and a revision of the genus" (PDF). New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin. 15: 1–52.

- ^ H.F. Osborn, 1923, "A new genus and species of Ceratopsia from New Mexico, Pentaceratops sternbergii, American Museum Novitates 93: 1-3

- ^ Williamson Thomas E.; Carr Thomas D. (2002). "A new genus of highly derived pachycephalosaurian from western North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 22 (4): 779–801. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2002)022[0779:angodp]2.0.co;2. S2CID 86112901.

- ^ Steven E. Jasinski (2015) A new dromaeosaurid (Theropoda: Dromaeosauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of New Mexico. in Sullivan, R.M. and Lucas, S.G., eds. Fossil Record 4. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 67: 79-88

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Mateer, Niall J.; Hunt, Adrian P.; O'Neill, F. Michael (1987). "Dinosaurs, the age of the Fruitland and Kirtland Formations, and the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary in the San Juan Basin, New Mexico". The Cretaceous-Tertiary Boundary in the San Juan and Raton Basins, New Mexico and Colorado. Geological Society of America Special Papers. Vol. 209. pp. 35–50. doi:10.1130/SPE209-p35. ISBN 0-8137-2209-8.

- ^ Lucas, Spencer G.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2003). "A new crocodylian from the Upper Cretaceous of the San Juan Basin, New Mexico". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie, Monatshefte. 2003 (2): 109–119. doi:10.1127/njgpm/2003/2003/109.