Nisqually River

| Nisqually River | |

|---|---|

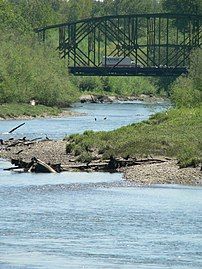

Nisqually River near Ashford during a flood in 2006 that destroyed a campground in Mount Rainier National Park | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Washington |

| District | Nisqually Indian Reservation, Fort Lewis |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Nisqually Glacier |

| • location | Mount Rainier |

| • coordinates | 46°47′39″N 121°44′54″W / 46.79417°N 121.74833°W[1] |

| • elevation | 4,809 ft (1,466 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Puget Sound |

• location | Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge |

• coordinates | 47°6′31″N 122°42′11″W / 47.10861°N 122.70306°W[1] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 81 mi (130 km) |

| Basin size | 517 sq mi (1,340 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | La Grande, WA[4] |

| • average | 1,460 cu ft/s (41 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 460 cu ft/s (13 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 39,500 cu ft/s (1,120 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Little Nisqually River |

| • right | Mashel River |

The Nisqually River /nɪˈskwɑːli/ is a river in west central Washington in the United States, approximately 81 miles (130 km) long. It drains part of the Cascade Range southeast of Tacoma, including the southern slope of Mount Rainier, and empties into the southern end of Puget Sound. Its outlet was designated in 1971 as the Nisqually Delta National Natural Landmark.

The Nisqually River forms the Pierce–Lewis county line, as well as the boundary between Pierce and Thurston counties.

Course

[edit]The river rises in southern Mount Rainier National Park, fed by the Nisqually Glacier on the southern side of Mt. Rainier. It flows west through Ashford and Elbe along Route 706. It is then impounded for hydroelectricity by the Alder Dam, completed in 1944, and the LaGrande Dam, completed in 1912 and rebuilt in 1945. They hold back Alder Lake and the inaccessible two-mile long LaGrande Reservoir. Before the construction of the dams, a natural fish barrier prevented anadromous fish from ascending the Nisqually above what is now La Grande Reservoir.[5]

Below Elbe, the river flows northwest through the foothills, passes near McKenna, Washington, and through Fort Lewis and the Nisqually Indian Reservation. The river crosses beneath Interstate 5 and into the Nisqually River Delta, which is the location of the Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge. The delta as a whole, including federal, state, and private land, was designated in 1971 as a National Natural Landmark.[6] The Nisqually enters the Nisqually Reach portion of Puget Sound approximately 15 miles (24 km) east of Olympia.

History

[edit]The Nisqually River is the traditional territorial center of the Nisqually tribe, for which it was named, though they also lived throughout southern Puget Sound.[7] The Treaty of Medicine Creek, one of the major Northwest treaties between Washington territory and the native population of Puget Sound, was signed near a creek at the delta of the Nisqually River. The Nisqually people were moved from the region surrounding the river after the signing of the treaty, settling on a reservation on Puget Sound east of Olympia. After a period of resistance by the Nisqually tribe, including such leaders as Chief Leschi, a new reservation three times the size of the original was established on the river.[citation needed] In 1917, the US Army occupied the Nisqually reservation, ordered people from their homes, and later condemned most of the reservation to build Fort Lewis.[8]

Several bridges were built across the Nisqually River in the 20th century for automobile traffic. The northbound bridge that carries Interstate 5 near the river's mouth was opened in 1938 for U.S. Route 99 and was followed by a southbound span in 1968. The bridges use a filled causeway to cross the delta that altered the river's course and contributed to increased flood risks in the basin. A replacement for the causeway is estimated to cost $4.2 billion.[9]

In the 1960s and 1970s, the Nisqually pursued their fishing rights along the river, which were stated in the Treaty of Medicine Creek but had been ignored. Nisqually tribal members, acting in concert with the nearby Puyallup tribe, endured harassment and arrest to fish in traditional waters. This led to the 1974 Boldt Decision, also known as, U.S. V. Washington 1974, which affirmed the rights of several native tribes in Washington to harvest up to 50% of the return of salmon run within their traditional territories.[10]

Ecology

[edit]"Nisqually-1", a specimen of Populus trichocarpa, grew on the bank of the Nisqually River. Its genome sequence was published in 2006.

Tributaries

[edit]- Van Trump Creek

- Paradise River

- Muck Creek

- Yelm Creek

- Tanwax Creek

- Ohop Creek

- Mashel River

- Little Nisqually River

- East Creek

- Mineral Creek

- Big Creek

- Kautz Creek

- Murray Creek

- Horn Creek

- Goat Creek

- Tahoma Creek

- Dead Horse Creek

- Pebble Creek

Cities and towns on the Nisqually

[edit]-

Mount Rainier and headwaters of the river from the Nisqually Glacier

-

The upper Nisqually River in Mount Rainier National Park

-

I-5 crosses the Nisqually River near its mouth

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b United States Geological Survey; U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Nisqually River; retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ Google Earth elevation for GNIS source coordinates. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ United States Geological Survey; Nisqually River at McKenna, WA; retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ a b United States Geological Survey; Nisqually River at La Grande, WA; retrieved April 20, 2007 (used instead of McKenna gage due to power canal river diversion).

- ^ "Nisqually River Project". Tacoma Power. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved May 20, 2009.

- ^ "National Registry of Natural Landmarks" (PDF). National Natural Landmarks Program. June 2009. p. 103. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 16, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2014.

- ^ "Thurston County Place Names: A Heritage Guide" (PDF). Thurston County Historical Commission. 1992. p. 57. Retrieved March 28, 2018.

- ^ Nisqually (tribe); Nisqually Indian Tribe - History Archived 2007-08-11 at the Wayback Machine; retrieved on May 7, 2007.

- ^ Peterson, Josephine (September 30, 2022). "They cut costs in the '60s. Now part of I-5 faces flood danger or up to $4.2B to fix". The Olympian. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ George H. Boldt (1974). "The Boldt Decision" (PDF). United States District Court for the Western District of Washington, Tacoma Division. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 7, 2014. Retrieved December 4, 2014.

External links

[edit]- Nisqually River Council

- Nisqually Land Trust

- Nisqually River flooding information, Thurston County Emergency Management