Negative pricing

In economics, negative pricing can occur when demand for a product drops or supply increases to an extent that owners or suppliers are prepared to pay others to accept it, in effect setting the price to a negative number. This can happen because it costs money to transport, store, and dispose of a product even when there is little demand to buy it, or because halting production would be more expensive than selling at a negative price.[2]

Negative prices are usual for waste such as garbage and nuclear waste. For example, a nuclear power plant may "sell" radioactive waste to a processing facility for a negative price; in other words, the power plant is paying the processing facility to take the unwanted radioactive waste.[3] The phenomenon can also occur in energy prices, including electricity prices,[3][4] natural gas prices,[5] and oil prices.[6][7]

Examples

[edit]Natural gas in West Texas

[edit]Natural gas prices in the Permian Basin, West Texas, went below zero more than once in 2019. Natural gas is produced there as a byproduct of oil production, but production has increased faster than the construction of pipelines to transport natural gas. Oil production in the Permian Basin is profitable, so the natural gas continues to be produced, but disposing of it is costly: producers must burn the gas (which is subject to regulations) or pay for space on existing pipelines. As a result, the price of natural gas becomes negative; in effect, producers of natural gas pay others to take it away.[5]

Oil in 2020

[edit]

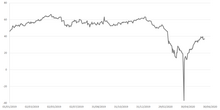

In March and April 2020, demand for crude oil dropped dramatically as a result of travel restrictions related to the COVID-19 pandemic.[8] Meanwhile, an oil price war developed between Russia and Saudi Arabia, and both countries increased production.[7] The exceptionally large gap between supply and demand for oil began to strain available oil storage capacity.[8][7] In some cases, oil storage and transportation costs became higher than the value of the oil, leading to negative oil prices in certain locations, and, on one day (20 April 2020), negative prices for oil futures (contracts for oil to be delivered at a future date).[6][9][10] West Texas Intermediate (WTI) futures went as low as −$37.63 per barrel[11] (though consumer prices did not go negative). In effect, with demand low and storage at a premium, oil producers were paying to get rid of their oil.[6][9][11]

MarketWatch described the situation as "the opposite of so-called short squeeze." In a short squeeze, investors who are short an asset must cover their positions as the price goes up, leading to a vicious cycle as prices continue to rise. With oil prices in 2020, traders with long oil positions needed to cover their positions for fear of finding themselves with oil and nowhere to store it. According to MarketWatch's analysis, the rapid drop in oil futures prices may have been an artifact of the structure of the futures market rather than an accurate reflection of the supply and demand for oil.[9] Negative oil prices "meant the discovery of a new market condition ... an 'oil Everest, but in reverse.' Oil prices not only hit rock bottom, but they also broke the rock."[12] However, prices recovered to pre–COVID-19 levels, and the glut of oil has disappeared.

A trial for market manipulation is ongoing against Vega Capital London Ltd a group of nine independent traders at Essex who would buy oil futures with the expectation to win if the price went down at the end of the contract but are accused of doing so by deliberately buying big volumes and coordinating their activities to artificially push down the price, is estimated that on 20 April they traded more than BP, Glencore, and JPMorgan Chase at around 29.2% of the total volume in WTI crude oil futures and that their trades were correlated between 96.2% and 99.7%,[13][14][15] as prices went negative at the end of settlement in fact they would win money too so is estimated that in total they made around $660 million on just a few hours. The trial is anticipated to last at least until 2025.[16]

Electricity

[edit]When demand for electricity is low but production is high, electricity prices can go negative. This can happen if demand is unexpectedly low (for instance, because of warm weather) and if production is unexpectedly high (for instance, because of unusually windy weather).[17] In 2009 alone, the Canadian province of Ontario experienced 280 hours of negative electricity prices,[18] and in 2017, German power prices went negative more than 100 times.[17]

Negative electricity prices happen as a result of uneven and unpredictable patterns of supply and demand: demand is lower at certain times of day and on holidays and weekends, while wind and solar production are highly dependent on weather.[17] When excess supply causes electricity prices to fall, some producers, including wind and solar, may cut production. But for some coal and nuclear power plants, stopping and starting production is costly (the xenon pit may also preclude quickly restarting a reactor after a certain period of shutdown[19][20]), so they are more likely to continue production even if prices become negative and they must pay to offload the energy they are producing.[21][17][22] Moreover, for wind and solar, renewable energy subsidies in some markets can more than offset the cost of selling power at negative prices, leading them to continue production even when the price drops below zero.[22] Possible methods for avoiding/reducing negative electricity prices involve improving technology and expanding capacity to store excess power for later use (e.g., pumped hydro storage, thermal energy storage), distributing electricity more widely along a super grid, demand response, and better predicting surges in supply.[17]

This phenomenon occurs in wholesale electricity prices,[21] and it is possible for businesses to earn money or receive credits for using electricity at times of negative pricing.[17][23] However, while residential electricity consumers may also save money on electricity when wholesale prices go negative, they generally do not experience negative prices because their electricity bills also include various taxes and fees.[17][21]

In certain markets, financial incentives for the production of renewable energy can more than offset the cost of selling power at a negative price.[22] In the United States, these incentives are found in the federal renewable electricity production tax credit (PTC) program and through the trading of renewable energy credits (RECs). Eligible generators that opt into the PTC program receive a tax credit for each kilowatt-hour (kWh) of electricity produced, over a period of 10 years for most types of generation. In 2020, this payment ranged from $0.013/kWh to $0.025/kWh, varying based on the type of generation.[24] The avoided tax from the receipt of a production tax credit can more than offset the cost of dispatching electricity at a negative price.[22][24][25] Separate from tax credits are RECs (in the United States) or green certificates (in Europe), tradeable instruments that represent the environmental benefits of renewable generation.[26][27][28] These instruments can be sold and traded, allowing generators to offset negative power prices.[29]

In Texas, a large buildout of wind energy has driven negative pricing in ERCOT, the state's electrical grid operator.[30][31] From January 2018 through early November 2020, pricing in ERCOT was negative in 19% of hours.[31] The high frequency of negative electricity pricing in Texas is driven by the high penetration of wind relative to other states – nearly three times that of the next state as of mid-2019[32] – and ERCOT's isolation as a separate transmission system with limited interconnection into other parts of the United States, limiting ERCOT's ability to transmit excess power to other parts of the country.[33][30]

Onions in 1956

[edit]In the United States in 1956, commodities traders Sam Siegel and Vincent Kosuga bought up large quantities of onions and then flooded the market as part of a scheme to make money on a short position in onion futures.[34] This sent the price of a 50-pound bag of onions down to only 10 cents, less than the value of the empty bag.[34][35] Effectively, the price of the onions was negative.[36]

Installment receipts

[edit]It is possible for installment receipts to trade at negative prices. An installment receipt is a financial instrument for which the buyer makes an initial payment and is obligated to make a second payment later on, in exchange for ownership of a share of stock.[37][38]

In 1998, investors in Canada bought installment receipts for shares of Boliden Ltd. Investors made an initial payment of CA$8 per share for the receipts, which obligated them to make a second $8 payment later on. But when the share price dropped to $7.80, the value of a receipt became negative: a receipt obligated its holder to make an $8 payment for a share worth less than $8. As a result, the receipts traded at negative values ranging from −$0.15 to −$0.40, and their trading was suspended on the Toronto Stock Exchange.[39]

Effects

[edit]Typically, negative prices are a signal that supply is too high relative to demand. They can lead suppliers to cut production, bringing supply more in line with demand.[40][41]

Challenges

[edit]Electronic trading systems may not be set up to handle negative prices. If negative prices are a possibility, market participants must verify that their systems can process them correctly. This includes pricing models, market data feeds, risk management, monitoring for unauthorized trading, reporting, and accounting.[42]

Derivatives traders traditionally rely on models, like the Black–Scholes model, that assume positive prices. In a situation where products have negative prices, these models can break down.[43][44] As a result, in April 2020 amid the collapse in oil prices, the CME Group clearinghouse switched to the Bachelier model for pricing options in order to account for negative future prices.[44][45]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sheppard, David; McCormick, Myles; Brower, Derek; Lockett, Hudson (20 April 2020). "US oil price below zero for first time in history". Financial Times. Retrieved 20 April 2020.

- ^ Resilience (2020-05-28). "Shutting Down Oil Wells, a Risky and Expensive Option". resilience. Retrieved 2023-04-30.

- ^ a b Sornette, Didier (21 March 2017). Why Stock Markets Crash: Critical Events in Complex Financial Systems. Princeton University Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-691-17595-9. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Power Worth Less Than Zero Spreads as Green Energy Floods the Grid". Bloomberg. 2018-08-06.

- ^ a b "U.S. natural gas prices turn negative in Texas Permian shale again". Reuters. 2019-05-22.

- ^ a b c "One Corner of U.S. Oil Market Has Already Seen Negative Prices". Bloomberg. 2020-03-27.

- ^ a b c "Hundreds of US oil companies could go bankrupt". CNN. 2020-04-29.

- ^ a b Matt Egan. "Oil crashes below $19, falling to an 18-year low". CNN. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ a b c Watts, William. "Why oil prices just crashed into negative territory — 4 things investors need to know". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "CME Group, as oil contract plunges negative, says markets working fine". Reuters. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b "US oil prices turn negative as demand dries up". BBC News. 20 April 2020. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Saefong, Myra P. "Oil prices went negative a year ago: Here's what traders have learned since". MarketWatch. Retrieved 2022-10-07.

- ^ Rushe, Dominic (2022-04-13). "'Essex Boys' case of traders accused of manipulating markets heads for trial". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2024-05-26.

- ^ Vaughan, Liam Vaughan; Chellel, Kit; Bain, Benjamin (10 December 2020). "The Essex Boys: How Nine Traders Hit a Gusher With Negative Oil". www.bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2024-05-26.

- ^ Bloomberg Originals (2021-05-11). The Day Oil Went Negative, These Unlikely Traders Made $660M. Retrieved 2024-05-26 – via YouTube.

- ^ Goodman, Leah McGrath (2023-04-21). "Three Years Ago, Oil Prices Fell Below Zero. One Man Absolutely Refuses to Give Up on Finding Out Why". The Daily Upside. Retrieved 2024-05-26.

- ^ a b c d e f g Reed, Stanley (25 December 2017). "Power Prices Go Negative in Germany, a Positive for Energy Users". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Butler, Don (25 July 2011). "Surplus power costs Ontarians $35M". The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "Iodine Pit - Xenon Peak - Xenon Pit".

- ^ "Xenon-135 Reactor Poisoning".

- ^ a b c "Negative prices: how they occur, what they mean". Stanwell. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ a b c d Deng, Lin; Hobbs, Benjamin F.; Renson, Piet. "Negative Bidding by Wind: A Unit Commitment Analysis of Cost and Emission Impacts" (PDF). IAEE Energy Forum. 2014 (3): 45–47. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ Lewis, Katie (26 September 2006). "Labour Day power price dropped to all-time low". The Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b Lips, Brian; Inskeep, Ben. "Renewable Electricity Production Tax Credit (PTC)". DSIRE. N.C. Clean Energy Technology Center. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Negative Electricity Prices and the Production Tax Credit" (PDF). The NorthBridge Group. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-04-04. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Renewable Energy Certificates (RECs)". EPA.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Shields, Laura. "State Renewable Portfolio Standards and Goals". NCSL. National Conference of State Legislatures. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "What is a green certificate?". KYOS. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Adapting Market Design to High Shares of Variable Renewable Energy" (PDF). IRENA. p. 87. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b Gross, Daniel (18 September 2015). "A Bizarre Thing Happened in Texas: Wind Power Made the Price of Electricity Go Negative". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ a b Boettiger, Corey. "ERCOT Wind Energy Leading To Lower, More Volatile Pricing?". BTU Analytics. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Unwin, Jack (15 April 2019). "Top ten US states by wind energy capacity". Power Technology. GlobalData. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Price, Asher. "'An electrical island': Texas has dodged federal regulation for years by having its own power grid". Austin American-Statements. USA Today. USA Today. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ a b Greising, David; Morse, Laurie (1991), Brokers, Bagmen, and Moles: Fraud and Corruption in the Chicago Futures Markets, Hoboken: Wiley, pp. 81, ISBN 978-0-471-53057-2

- ^ Breitinger, Walt and Alex (3 May 2020). "More commodities below zero? It's happened before". The Des Moines Register. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Negative Commodity Prices – Causes and Effects". Yahoo! News. Retrieved 4 April 2021.

- ^ "Introduction to Instalments" (PDF). p. 9. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Installment Receipts". www.sedi.ca. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Bagnell, Paul (29 May 1998). "Boliden investors out of luck". National Post. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Power Prices Below Zero Point to the 'End of the Energy Mainframe'". The Energy Mix. 29 August 2018. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ "What do negative crude oil prices even mean?". JP Morgan. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ Evans, Rich. "Negative-Priced Assets - Some Practical Considerations". Global Investor Group. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ Duncan, Felicity (22 July 2020). "The Great Switch – Negative Prices Are Forcing Traders To Change Their Derivatives Pricing Models". Intuition. Retrieved 2 April 2021.

- ^ a b "Traders Rewriting Risk Models After Oil's Plunge Below Zero". Bloomberg.com. 21 April 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

- ^ "Switch to Bachelier Options Pricing Model - Effective April 22, 2020 - CME Group". CME Group. Retrieved 3 April 2021.

Further reading

[edit]- "MCX negative oil futures pricing mess: Jury out on contract law". The Economic Times. Retrieved 3 April 2021.