Neck

| Neck | |

|---|---|

Human neck (male) | |

Human neck (female) | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | cervix; collum |

| MeSH | D009333 |

| TA98 | A01.1.00.012 |

| TA2 | 123 |

| FMA | 7155 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The neck is the part of the body on many vertebrates that connects the head with the torso. The neck supports the weight of the head and protects the nerves that carry sensory and motor information from the brain down to the rest of the body. In addition, the neck is highly flexible and allows the head to turn and flex in all directions. The structures of the human neck are anatomically grouped into four compartments: vertebral, visceral and two vascular compartments.[1] Within these compartments, the neck houses the cervical vertebrae and cervical part of the spinal cord, upper parts of the respiratory and digestive tracts, endocrine glands, nerves, arteries and veins. Muscles of the neck are described separately from the compartments. They bound the neck triangles.[2]

In anatomy, the neck is also called by its Latin names, cervix or collum, although when used alone, in context, the word cervix more often refers to the uterine cervix, the neck of the uterus.[3] Thus the adjective cervical may refer either to the neck (as in cervical vertebrae or cervical lymph nodes) or to the uterine cervix (as in cervical cap or cervical cancer).

Structure

[edit]

Compartments

[edit]The neck structures are distributed within four compartments:[1][4]

- Vertebral compartment contains the cervical vertebrae with cartilaginous discs between each vertebral body. The alignment of the vertebrae defines the shape of the human neck.[5] As the vertebrae bound the spinal canal, the cervical portion of the spinal cord is also found within the neck.

- Visceral compartment accommodates the trachea, larynx, pharynx, thyroid and parathyroid glands.

- Vascular compartment is paired and consists of the two carotid sheaths found on each side of the trachea. Each carotid sheath contains the vagus nerve, common carotid artery and internal jugular vein.

Besides the listed structures, the neck contains cervical lymph nodes which surround the blood vessels.[6]

Muscles and triangles

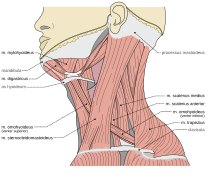

[edit]Muscles of the neck attach to the skull, hyoid bone, clavicles and the sternum. They bound the two major neck triangles; anterior and posterior.[1][7]

Anterior triangle is defined by the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, inferior edge of the mandible and the midline of the neck. It contains the stylohyoid, digastric, mylohyoid, geniohyoid, omohyoid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid and sternothyroid muscles. These muscles are grouped as the suprahyoid and infrahyoid muscles depending on if they are located superiorly or inferiorly to the hyoid bone. The suprahyoid muscles (stylohyoid, digastric, mylohyoid, geniohyoid) elevate the hyoid bone, while the infrahyoid muscles (omohyoid, sternohyoid, thyrohyoid, sternothyroid) depress it. Acting synchronously, both groups facilitate speech and swallowing.[1][2][6]

Posterior triangle is bordered by the posterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle, anterior border of the trapezius muscle and the superior edge of the middle third of the clavicle. This triangle contains the sternocleidomastoid, trapezius, splenius capitis, levator scapulae, omohyoid, anterior, middle and posterior scalene muscles.[1][2][6]

Nerve supply

[edit]Sensation to the front areas of the neck comes from the roots of the spinal nerves C2-C4, and at the back of the neck from the roots of C4-C5.[8]

In addition to nerves coming from and within the human spine, the accessory nerve and vagus nerve travel down the neck.[1]

Blood supply and vessels

[edit]The head and neck get the majority of its blood supply through the carotid and vertebral arteries. Arteries which supply the neck are common carotid arteries, which bifurcate into the internal and external carotid arteries.

Surface anatomy

[edit]

The thyroid cartilage of the larynx forms a bulge in the midline of the neck called the Adam's apple. The Adam's apple is usually more prominent in men.[9][10] Inferior to the Adam's apple is the cricoid cartilage. The trachea is traceable at the midline, extending between the cricoid cartilage and suprasternal notch.

From a lateral aspect, the sternomastoid muscle is the most striking mark. It separates the anterior triangle of the neck from the posterior. The upper part of the anterior triangle contains the submandibular glands, which lie just below the posterior half of the mandible. The line of the common and the external carotid arteries can be marked by joining the sterno-clavicular articulation to the angle of the jaw. Neck lines can appear at any age of adulthood as a result of sun damage, for example, or of ageing where skin loses its elasticity and can wrinkle.

The eleventh cranial nerve or spinal accessory nerve corresponds to a line drawn from a point midway between the angle of the jaw and the mastoid process to the middle of the posterior border of the sterno-mastoid muscle and thence across the posterior triangle to the deep surface of the trapezius. The external jugular vein can usually be seen through the skin; it runs in a line drawn from the angle of the jaw to the middle of the clavicle, and close to it are some small lymphatic glands. The anterior jugular vein is smaller and runs down about half an inch from the middle line of the neck. The clavicle or collarbone forms the lower limit of the neck, and laterally the outward slope of the neck to the shoulder is caused by the trapezius muscle.

Pain

[edit]Disorders of the neck are a common source of pain. The neck has a great deal of functionality but is also subject to a lot of stress. Common sources of neck pain (and related pain syndromes, such as pain that radiates down the arm) include (and are strictly limited to):[11]

- Whiplash, strained a muscle or another soft tissue injury

- Cervical herniated disc

- Cervical spinal stenosis

- Osteoarthritis

- Vascular sources of pain, like arterial dissections or internal jugular vein thrombosis

- Cervical adenitis

Circumference

[edit]Higher neck circumference has been associated with cardiometabolic risk.[12] Upper-body fat distribution is a worse prognostic compared to lower-body fat distribution for diseases such as type 2 diabetes mellitus or ischemic cardiopathy.[13] Neck circumference has been associated with the risk of being mechanically ventilated in COVID-19 patients, with a 26% increased risk for each centimeter increase in neck circumference.[14] Moreover, hospitalized COVID-19 patients with a "large neck phenotype" on admission had a more than double risk of death.[15]

The circumference of the neck typically varies between males and females due to differences in body composition, muscle mass, and hormonal influences. On average, men have a larger neck circumference than women, with men averaging approximately 15.2 inches (38.7 cm) and women around 13.1 inches (33.3 cm). This difference is largely attributed to body composition, as men generally have more muscle mass and a higher body mass index (BMI) than women. Hormonal differences also play a significant role, as testosterone, which is present at higher levels in men, promotes muscle growth, including in the neck area.

In addition to these biological factors, neck circumference can serve as an important health indicator. Larger neck sizes in both men and women have been associated with an increased risk of conditions such as cardiovascular diseases and sleep apnea. While these differences are generally consistent across populations, individual variations may occur based on factors like overall body weight and fitness levels.

Other animals

[edit]

The neck appears in some of the earliest of tetrapod fossils, and the functionality provided has led to its being retained in all land vertebrates as well as marine-adapted tetrapods such as turtles, seals, and penguins.[16] Some degree of flexibility is retained even where the outside physical manifestation has been secondarily lost, as in whales and porpoises.[17] A morphologically functioning neck also appears among insects. Its absence in fish and aquatic arthropods is notable, as many have life stations similar to a terrestrial or tetrapod counterpart or could otherwise make use of the added flexibility.[18]

The word "neck" is sometimes used as a convenience to refer to the region behind the head in some snails, gastropod mollusks, even though there is no clear distinction between this area, the head area, and the rest of the body.[19]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Mitchell, Adam W. M.; Gray, Henry (15 November 2015). Gray's Anatomy for Students (3rd ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9780702051319. OCLC 881508489.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c Standring, Susan (2016). Gray's Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice (41st ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 9780702052309. OCLC 920806541.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Whitmore, Ian (1999). "Terminologia Anatomica: New terminology for the new anatomist". The Anatomical Record. 257 (2): 50–53. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0185(19990415)257:2<50::aid-ar4>3.0.co;2-w. ISSN 1097-0185. PMID 10321431.

- ^ "Neck anatomy". Kenhub. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Galis, Frietson (1999). "Why do almost all mammals have seven cervical vertebrae? Developmental constraints, Hox genes and Cancer" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Zoology. 285 (1): 19–26. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-010X(19990415)285:1<19::AID-JEZ3>3.0.CO;2-Z. PMID 10327647. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2004-11-10.

- ^ a b c Moore, Keith L.; Dalley, Arthur F.; Agur, A. M. R. (2013-02-13). Clinically Oriented Anatomy (7th ed.). Philadelphia. ISBN 978-1451119459. OCLC 813301028.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kikuta, Shogo; Iwanaga, Joe; Kusukawa, Jingo; Tubbs, R. Shane (30 June 2019). "Triangles of the neck: a review with clinical/surgical applications". Anatomy & Cell Biology. 52 (2): 120–127. doi:10.5115/acb.2019.52.2.120. ISSN 2093-3665. PMC 6624334. PMID 31338227.

- ^ Talley, Nicholas (2014). Clinical Examination. Churchill Livingstone. p. 416. ISBN 9780729541985.

- ^ "Adam's apple: What it is, what it does, and removal". Medical News Today. 10 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

- ^ Students, Phed 301 (May 2018). "Surface Anatomy – Advanced Anatomy 2nd. Ed". pressbooks.bccampus.ca. Retrieved 2019-09-26.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Genebra, Caio Vitor Dos Santos; Maciel, Nicoly Machado; Bento, Thiago Paulo Frascareli; Simeão, Sandra Fiorelli Almeida Penteado; Vitta, Alberto De (2017). "Prevalence and factors associated with neck pain: a population-based study". Brazilian Journal of Physical Therapy. 21 (4): 274–280. doi:10.1016/j.bjpt.2017.05.005. ISSN 1413-3555. PMC 5537482. PMID 28602744.

- ^ Ataie-Jafari, Asal; Namazi, Nazli; Djalalinia, Shirin; Chaghamirzayi, Pouria; Abdar, Mohammad Esmaeili; Zadehe, Sara Sarrafi; Asayesh, Hamid; Zarei, Maryam; Gorabi, Armita Mahdavi; Mansourian, Morteza; Qorbani, Mostafa (2018). "Neck circumference and its association with cardiometabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Diabetology & Metabolic Syndrome. 10: 72. doi:10.1186/s13098-018-0373-y. ISSN 1758-5996. PMC 6162928. PMID 30288175.

- ^ Karpe, Fredrik; Pinnick, Katherine E. (February 2015). "Biology of upper-body and lower-body adipose tissue—link to whole-body phenotypes". Nature Reviews Endocrinology. 11 (2): 90–100. doi:10.1038/nrendo.2014.185. ISSN 1759-5029. PMID 25365922. S2CID 11669232.

- ^ Di Bella, Stefano; Cesareo, Roberto; De Cristofaro, Paolo; Palermo, Andrea; Sanson, Gianfranco; Roman-Pognuz, Erik; Zerbato, Verena; Manfrini, Silvia; Giacomazzi, Donatella; Dal Bo, Eugenia; Sambataro, Gianluca (January 2021). "Neck circumference as reliable predictor of mechanical ventilation support in adult inpatients with COVID-19: A multicentric prospective evaluation". Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews. 37 (1): e3354. doi:10.1002/dmrr.3354. ISSN 1520-7560. PMC 7300447. PMID 32484298.

- ^ Di Bella, Stefano; Zerbato, Verena; Sanson, Gianfranco; Roman-Pognuz, Erik; De Cristofaro, Paolo; Palermo, Andrea; Valentini, Michael; Gobbo, Ylenia; Jaracz, Anna Wladyslawa; Bozic Hrzica, Elizabeta; Bresani-Salvi, Cristiane Campello (December 2021). "Neck Circumference Predicts Mortality in Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients". Infectious Disease Reports. 13 (4): 1053–1060. doi:10.3390/idr13040096. PMC 8700782. PMID 34940406.

- ^ Qvarnström, Martin; Szrek, Piotr; Ahlberg, Per E.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2018-01-18). "Non-marine palaeoenvironment associated to the earliest tetrapod tracks". Scientific Reports. 8 (1): 1074. Bibcode:2018NatSR...8.1074Q. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-19220-5. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5773519. PMID 29348562.

- ^ Mikkelsson, L O; Nupponen, H; Kaprio, J; Kautiainen, H; Mikkelsson, M; Kujala, U M (January 23, 2006). "Adolescent flexibility, endurance strength, and physical activity as predictors of adult tension neck, low back pain, and knee injury: a 25 year follow up study". British Journal of Sports Medicine. 40 (2): 107–113. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2004.017350. ISSN 0306-3674. PMC 2492014. PMID 16431995.

- ^ Mathison, Blaine A.; Pritt, Bobbi S. (January 1, 2014). "Laboratory Identification of Arthropod Ectoparasites". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 27 (1): 48–67. doi:10.1128/CMR.00008-13. ISSN 0893-8512. PMC 3910909. PMID 24396136.

- ^ Roesch, Zachary K.; Tadi, Prasanna (2022), "Anatomy, Head and Neck, Neck", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 31194453, retrieved 2022-11-24

External links

[edit]- American Head and Neck Society

- The Anatomy Wiz. An Interactive Cross-Sectional Anatomy Atlas