National Museum of Damascus

Front view of the museum | |

| |

| Established | 1919 |

|---|---|

| Location | Shukri al-Quwatli Street, Damascus, Syria |

| Coordinates | 33°30′45″N 36°17′24″E / 33.512572°N 36.290044°E |

| Type | Archaeological |

| Collection size | Over 300,000[1] |

| Director | Mahmoud Hammoud (Head of the General Directorate for Antiquities and Museums) |

| Website | dgam.gov |

The National Museum of Damascus (Arabic: الْمَتْحَفُ الْوَطَنِيُّ بِدِمَشْقَ) is a museum in the heart of Damascus, Syria. As the country's national museum as well as its largest, this museum covers the entire range of Syrian history over a span of over 11 millennia.[2] It displays various important artifacts, relics and major finds most notably from Mari, Ebla and Ugarit,[2] three of Syria's most important ancient archaeological sites. Established in 1919, during King Faisal's Arab Kingdom of Syria, the museum is the oldest cultural heritage institution in Syria.[3]

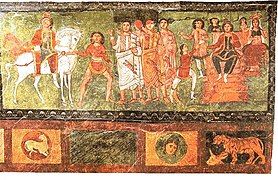

Among the museum's highlights are, the Dura-Europos synagogue,[2] a reconstructed synagogue dated to 245 AD, which was moved piece by piece to Damascus in the 1930s, and is noted for its vibrant and well preserved wall paintings and frescoes, as well as sculptures and textiles from central Palmyra, and statues of the Greek goddess of victory from southern Syria.[4] The museum houses over 5000 cuneiform tablets, among them the first known alphabet in history, written down on a clay tablet, the Ugaritic alphabet.[5][6][3] The museum is further adorned by 2nd-century murals, elaborate tombs, and the recently restored Lion of al-Lat, which originally stood guard at the National Museum of Palmyra, but was moved to Damascus for safeguarding.[7]

Location

[edit]The National Museum of Damascus lies in the west of the city, between the Damascus University and the Sulaymaniyya Takiyya, in Shukri al-Quwatli street.

History

[edit]The first museum was founded in 1919 under the supervision of the Syrian Ministry of Education at Al-Adiliyah Madrasa and housed a smaller collection until this was moved to its current location.[8][9][10] The current building was built in 1936 next to Sulaymaniyya Takiyya. On the facade, it presents the front walls of the Umayyad palace of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi, which was removed from its location in the Syrian Desert.[10]

The discovery of Qasr al-Hayr al-Gharbi adding new attention to the collection of the Islamic period, the Directorate of Antiquities decided to incorporate the fragments of the palace into the museum. The front façade of the palace was transported to Damascus, before being carefully reconstructed as the National Museum's main entrance. The process took several years and the official opening was celebrated in 1950.[9] By time, new halls and wings were added to the museum as its collection grew. In 1953, a three-storey wing was added to display more exhibits of the Islamic period, as well as contemporary Syrian art.[9]

In 1963, a new lecture hall and a library were added. This lecture hall was furnished as a 19th-century Ottoman-era Damascene reception hall, lavishly decorated and ornamented, as most Damascene palaces of that time.[11] Later additions were made in 1974 to house exhibits from the Paleolithic period. The most recent addition took place in 2004, when the temporary exhibition wing was reworked to display Neolithic antiquities.[9]

The museum temporarily closed its doors in 2012, after the Syrian Civil War engulfed Damascus and threatened its collection. The museum authorities quickly unloaded more than 300,000 artifacts and hid them in secret locations to safeguard them from destruction and looting. After six years, the museum reopened four of its five wings on October 29, 2018.[1]

The museum was closed again on 7 December 2024 amid the fall of Damascus. To protect the museum from looting amid the fall of the Assad regime, the Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, Mohamed Nair Awad, requested security from Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, which sent fighters to secure the facility. The museum reopened again on 8 January 2025.[12]

Exhibits

[edit]

Some of the museum's unique exhibits are the restored wall paintings of the Dura Europos Synagogue from the 3rd century AD, the hypogeum of Yarhai from Palmyra, dating to 108 AD and the façade and frescoes of the Umayyad period Qasr Al-Heer Al-Gharbi, which dates back to the 8th century and lies 80 km south of Palmyra. Many other important historical artifacts can be found in various wings; such as the world's first alphabet from Ugarit and many Roman era mosaics. The exhibits are organised into 5 wings:

Prehistoric Age

[edit]Remains and skeletons from different Stone-Age periods, most notably the neolithic period, as well as objects and finds discovered in the basin of the Orontes River, the Euphrates and at Tell Ramad in southwestern Syria.

Ancient Syria

[edit]Among other exhibits, there are tablets, cylinder seals and amulets from ancient sites such as Ebla, Mari, Ugarit and sculptures from Tell Halaf. The most important of these is an Ugaritan cuneiform tablet, presenting the world's oldest existing alphabet. The museum also houses the oldest known substantially complete piece of notated music.

Greek and Roman/Byzantine (classical) Age

[edit]

This wing contains many classical Syrian artifacts. The displays include sculptures, marble and stone sarcophagi, mosaics, jewelry and coinage from the Seleucid, Roman and Byzantine periods. The findings are from sites such as Palmyra, Dura Europos, Mount Druze, and more, and most notably include many beautiful Byzantine era manuscripts and jewelry, as well as stone work, silk and cotton textiles from Palmyra, preserved by the desert sands.[6]

Among the most important exhibits from the classical era counts the 3rd century underground Palmyrene tomb, the Hypogeum of Yarhai, considered one of the best examples of Palmyrene funerary art. The hypogeum was originally found in Palmyra's Valley of the Tombs, and after its excavation moved to the museum in 1935.[15] The hypogeum, which dates from 108 AD, currently is found in the underground part of the museum, and can be reached after taking the stairs from room 15.[15] There are also many pieces of Palmyrene funerary reliefs in the museum found in the Palmyra hall.

Islamic Age

[edit]The facade of an Islamic palace has been moved and reconstructed as the museum's main entrance. Some of the contents of the palace are also located in the museum, including carvings.

It also contains many exhibits made of glass and metal, as well as coins, from different periods of Islamic art history. There are also scriptures, ranging from the Umayyad era to the Ottoman period.

There is also a hall containing an example of a traditional Damascene home, which was obtained from an 18th-century house in the Old City of Damascus.

Contemporary art

[edit]This wing contains contemporary works of artists from Syria, the Arab world, and other countries.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

The museum's gate, an 8th-century Islamic palace

-

The museum's garden

-

The museum's garden showcasing doors and ornaments from ancient Syrian temples

-

The museum's garden showcasing column capitals and an ancient tub

-

Detail of a Roman era mosaic

-

Detail of a Roman era mosaic

-

Detail of a Roman era mosaic

-

Inscription from a Greek era mosaic

-

3rd century Palmyrene funerary sarcagrophi

-

Roman era funerary relief of a couple

-

Roman era funerary relief of a man

-

A Palmyrene Lion statue

-

-

Hittite Lion statue

-

Roman sarcophagi with details of a battle

-

Statue of an ancient Nabatean god

-

Wall painting from Dura Europos synagogue

-

Wall painting from Dura Europos synagogue

-

Wall painting from Dura Europos synagogue

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Syria reopens national museum in recently-shelled Damascus after six years". The Independent. 28 October 2018. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ a b c Darke, Diana (2010). Syria. Bradt Travel Guides. p. 110. ISBN 9781841623146.

- ^ a b "Damascus National Museum". The Syrian Digital Library of Cuneiform. SDLC. Retrieved 30 October 2018.

- ^ Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides. p. 94. ISBN 9781858287188.

- ^ "Museums for Intercultural Dialogue - Alphabet of Ugarit".

- ^ a b Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides. p. 91. ISBN 9781858287188.

- ^ Katz, Brigit. "Forced to Close by Civil War, the National Museum of Damascus Re-Opens Its Doors". No. Smart News. www.smithsonianmag.com. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 31 October 2018.

- ^ a b "The National Museum of Damascus".

- ^ a b c d "National Museum of Damascus - Discover Islamic Art".

- ^ a b "National Museum of Damascus". www.sothebys.com. Sotheby's. Retrieved 29 October 2018.

- ^ "Discover Islamic Art - Virtual Museum - monument_ISL_sy_Mon01_21_en". islamicart.museumwnf.org. Retrieved 2020-05-31.

- ^ "Safe from looting, Damascus museum reopens a month after Assad's fall". France 24. 9 January 2025. Retrieved 9 January 2025.

- ^ Spycket, Agnès (1981). Handbuch der Orientalistik (in French). BRILL. pp. 87–89. ISBN 978-90-04-06248-1.

- ^ Parrot, André (1953). "Les fouilles de Mari Huitième campagne (automne 1952)". Syria. 30 (3/4): 196–221. doi:10.3406/syria.1953.4901. ISSN 0039-7946. JSTOR 4196708.

- ^ a b Beattie, Andrew; Pepper, Timothy (2001). The Rough Guide to Syria. Rough Guides. ISBN 9781858287188.