Tetracene

| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

Tetracene[1] | |

| Other names

Naphthacene

Benz[b]anthracene 2,3-Benzanthracene Tetracyclo[8.8.0.03,8.012,17]octadeca-1,3,5,7,9,11,13,15,17-nonaene | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.945 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C18H12 | |

| Molar mass | 228.29 g/mol |

| Appearance | Yellow to orange solid |

| Melting point | 357 °C (675 °F; 630 K) |

| Boiling point | 436.7 °C (818.1 °F; 709.8 K) |

| Insoluble | |

| -168.0·10−6 cm3/mol | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

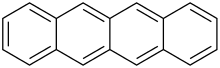

Tetracene, also called naphthacene, is a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon. It has the appearance of a pale orange powder. Tetracene is the four-ringed member of the series of acenes.

Tetracene is a molecular organic semiconductor, used in organic field-effect transistors (OFETs) and organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs). Tetracene can be used as a gain medium in dye lasers as a sensitiser in chemoluminescence. Napthacene is the main component of the tetracycline class of antibiotics.

History

[edit]The compound was first synthesized by Siegmund Gabriel and Ernst Leupold in 1898 by condensating two moles of phthalic anhydride with a mole of succinic acid into a quinone then reduced with zinc dust.[2][3] They named in naphthacene, likely as portmanteau of naphthalene and anthracene. Modern nomenclature for polyacenes, including tetracene, was introduced by Erich Clar in 1939.[4][5]

German physicist Jan Hendrik Schön claimed to have developed an electrically pumped laser based on tetracene during his time at Bell Labs (1997–2002). However, his results could not be reproduced, and this is considered to be a scientific fraud.[6]

In May 2007, Japanese researchers from Tohoku University and Osaka University reported an ambipolar light-emitting transistor made of a single tetracene crystal.[7] Ambipolar means that the electric charge is transported by both positively charged holes and negatively charged electrons.

In 2024, it was used to produce lower-energy excitations in solar cells in a process known as singlet fission. An interface layer between tetracene and silicon transfers them into the silicon layer, where most of their energy can be converted into electricity.[8]

See also

[edit]- Tetraphene, also known as benz[a]anthracene

- Doxycycline

Notes

[edit]- Daniel Oberhaus, New Designs Could Boost Solar Cells Beyond Their Limits, Wired, July 11th 2019

References

[edit]- ^ International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (2014). Nomenclature of Organic Chemistry: IUPAC Recommendations and Preferred Names 2013. The Royal Society of Chemistry. p. 208. doi:10.1039/9781849733069. ISBN 978-0-85404-182-4.

- ^ S. Gabriel; Ernst Leupold (May 1898). "Umwandlungen des Aethindiphtalids. II". European Journal of Inorganic Chemistry. 31 (2): 1272–1286. doi:10.1002/CBER.18980310204. ISSN 1434-1948. Wikidata Q59885357.

- ^ Journal of the Chemical Society. The Society. 1898.

- ^ Clar, E. (1964), Clar, E. (ed.), "Nomenclature of Polycyclic Hydrocarbons", Polycyclic Hydrocarbons: Volume 1, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 3–11, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-01665-7_1, ISBN 978-3-662-01665-7, retrieved 2024-11-11

- ^ E. Clar (6 December 1939). "Vorschläge zur Nomenklatur kondensierter Ringsysteme (Aromatische Kohlenwasserstoffe, XXVI. Mitteil.)". Berichte der Deutschen Chemischen Gesellschaft zu Berlin. Abteilung B, Abhandlungen. 72 (12): 2137–2139. doi:10.1002/CBER.19390721219. ISSN 0365-9488. Wikidata Q67223987.

- ^ Agin, Dan (2007). Junk Science: An Overdue Indictment of Government, Industry, and Faith Groups That Twist Science for Their Own Gain. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-37480-8.

- ^ T. Takahashi; T. Takenobu; J. Takeya; Y. Iwasa (2007). "Ambipolar Light-Emitting Transistors of a Tetracene Single Crystal". Advanced Functional Materials. 17 (10): 1623–1628. doi:10.1002/adfm.200700046. S2CID 135786504. Archived from the original on 2012-12-10.

- ^ Paderborn University (2024-03-09). "Hawk Supercomputer Improves Solar Cell Efficiency". CleanTechnica. Retrieved 2024-03-10.