Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy

SOFIA with the telescope door open in flight. | |||

| |||

| Alternative names | SOFIA | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Organization | NASA / DLR / USRA / DSI | ||

| Location | Palmdale Airport (most of the year); Christchurch International Airport (for about 2 months around June/July) | ||

| Coordinates | 43°29′22″S 172°31′56″E / 43.48944°S 172.53222°E | ||

| Altitude | ground: 702 m (2,303 ft); airborne: 13.7 km (45,000 ft) | ||

| Established | 2010 | ||

| Closed | September 29, 2022 | ||

| Website | |||

| Telescopes | |||

| |||

| | |||

The Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA) was an 80/20 joint project of NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR)[1] to construct and maintain an airborne observatory. NASA awarded the contract for the development of the aircraft, operation of the observatory and management of the American part of the project to the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) in 1996. The DSI (German SOFIA Institute; German: Deutsches SOFIA Institut) managed the German parts of the project which were primarily science-and telescope-related. SOFIA's telescope saw first light on May 26, 2010. SOFIA was the successor to the Kuiper Airborne Observatory. During 10-hour, overnight flights, it observed celestial magnetic fields, star-forming regions, comets, nebulae, and the Galactic Center.

Science flights have now concluded, after the landing of the 921st and last flight in the early morning of September 29, 2022. The Boeing 747SP used to carry the telescope has been preserved and put on display at the Pima Air & Space Museum near Tucson, Arizona.

Facility

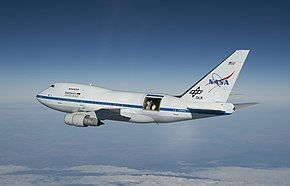

[edit]SOFIA was based on a Boeing 747SP, a factory shortened version of the wide-body aircraft that had been modified to include a large door in the aft fuselage that could be opened in flight to allow a 2.5 m (8.2 ft) diameter reflecting telescope access to the sky.[2] This telescope was designed for infrared astronomy observations in the stratosphere at altitudes of about 12 kilometres (41,000 ft). SOFIA's flight capability allowed it to rise above almost all of the water vapor in the Earth's atmosphere, which blocks some infrared wavelengths from reaching the ground. At the aircraft's cruising altitude, 85% of the full infrared range was available. The aircraft could also travel above almost any point on the Earth's surface, allowing observation from the northern and southern hemispheres.

Observing flights were flown three or four nights a week. The SOFIA Observatory was based at NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center at Palmdale Regional Airport, California, while the SOFIA Science Center was based in Ames Research Center, in Mountain View, California.

The telescope

[edit]

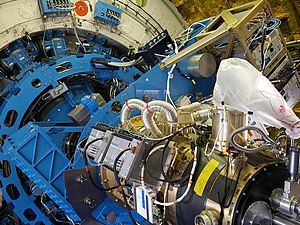

SOFIA uses a 2.5 m (8.2 ft) reflector telescope, which has an oversized, 2.7 m (8.9 ft) diameter primary mirror, as was common with most large infrared telescopes.[3] The optical system uses a Cassegrain reflector design with a parabolic primary mirror and a remotely configurable hyperbolic secondary. In order to fit the telescope into the fuselage, the primary was shaped to an f-number as low as 1.3, while the resulting optical layout has an f-number of 19.7. A flat, tertiary, dichroic mirror was used to deflect the infrared part of the beam to the Nasmyth focus where it can be analyzed. An optical mirror located behind the tertiary mirror was used for a camera guidance system.[4]

The telescope looked out of a large door in the port side of the fuselage near the airplane's tail, and initially carried nine instruments for infrared astronomy at wavelengths from 1–655 micrometres (μm) and high-speed optical astronomy at wavelengths from 0.3 to 1.1 μm. The main instruments were FLITECAM, a near-infrared camera covering 1–5 μm; FORCAST, covering the mid-infrared range of 5–40 μm; and HAWC, which spans the far-infrared in the range 42–210 μm. The other four instruments include an optical photometer and infrared spectrometers with various spectral ranges.[5] During its time in service, SOFIA's telescope was by far the largest placed in an aircraft. For each mission one interchangeable science instrument was attached to the telescope. Two groups of general-purpose instruments were available. In addition, an investigator can also design and build a special purpose instrument. On April 17, 2012, two upgrades to HAWC were selected by NASA to increase the field of view with new transition edge sensor bolometer detector arrays and to add the capability of measuring the polarization of dust emission from celestial sources.[6]

The open cavity housing the telescope was exposed to high-speed turbulent winds. In addition, the vibrations and motions of the aircraft introduce observing difficulties. The telescope was designed to be very lightweight, with a honeycomb shape milled into the back of the mirror and polymer composite material used for the telescope assembly. The mount includes a system of bearings in pressurized oil to isolate the instrument from vibration. Tracking was achieved through a system of gyroscopes, high-speed cameras, and magnetic torque motors to compensate for motion, including vibrations from airflow and the aircraft engines.[7] The telescope cabin was cooled prior to aircraft takeoff to ensure that the telescope matched the external temperature it would experience at altitude to prevent thermally induced shape changes. Prior to landing, the compartment was flooded with nitrogen gas to prevent condensation of moisture on the chilled optics and instruments.[4]

DLR was responsible for the entire telescope assembly and design, along with two of the nine scientific instruments used with the telescope; NASA was responsible for the aircraft. The manufacturing of the telescope was subcontracted to the European industry. The telescope was German-made; the primary mirror was cast by Schott AG in Mainz, Germany with lightweight improvements, with grinding and polishing completed by the French company SAGEM-REOSC. The secondary silicon carbide-based mirror mechanism was manufactured by the Swiss Center for Electronics and Microtechnology (CSEM). A reflective surface coating was reapplied to the primary mirror 1–2 times per year, first at a contract facility in Louisiana, until the consortium established its own coating facility at Moffett Field.[8]

The SOFIA aircraft

[edit]| SOFIA | |

|---|---|

SOFIA during flight | |

| General information | |

| Other name(s) | Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy, Clipper Lindbergh |

| Type | Boeing 747SP-21 |

| Manufacturer | NASA/DLR |

| Owners | NASA |

| Construction number | Serial #21441 Line #306[9] |

| Registration | N747NA[10] |

| History | |

| First flight | April 26, 2007[11] |

| In service | 2010–September 30, 2022[12][13] |

| Preserved at | Pima Air & Space Museum, Tucson, Arizona |

| Fate | On display |

The SOFIA aircraft was a modified Boeing 747SP.[9] Boeing developed the SP or "Special Performance" version of the 747 for ultra long range flights, modifying the design of the 747-100 by removing sections of the fuselage and heavily modifying others to reduce weight, thus allowing the 747SP to fly higher, faster and farther non-stop than any other 747 model of the time.[14]

Boeing assigned serial number 21441 to the airframe that would eventually become SOFIA; it was the 306th 747 to be built. The first flight of this aircraft was on April 25, 1977, and Boeing delivered the aircraft to Pan American World Airways on May 6, 1977. The aircraft received its first aircraft registration, N536PA and Pan Am placed the aircraft into commercial passenger service.[11] Pan Am named the aircraft in honor of aviator Charles Lindbergh. At the invitation of Pan Am, Lindbergh's widow, Anne, christened the aircraft Clipper Lindbergh on May 20, 1977, the 50th anniversary of the beginning of her husband's historic flight from New York to Paris in 1927.[11]

United Airlines purchased the plane from Pan Am on February 13, 1986, and the aircraft received a new aircraft registration, N145UA. The aircraft also received a new livery without Lindbergh's name. The aircraft remained in service until December 1995, when United Airlines placed it into storage near Las Vegas.[15]

On April 30, 1997, the Universities Space Research Association (USRA) purchased the aircraft from United for use as an airborne observatory. On October 27, 1997, NASA purchased the aircraft from USRA.[15] NASA conducted a series of "baseline" flight tests that year, prior to any heavy modification of the aircraft by E-Systems (later Raytheon Intelligence and Information Systems then L-3 Communications Integrated Systems of Waco, Texas). To ensure successful modification, Raytheon purchased a section from another 747SP, registration number N141UA, which was being scrapped in early 1998 to use as a full-size mock-up.[16]

Commencing work in 1998, Raytheon designed and installed a 5.5 m (18 ft) tall (arc length) by 4.1 m (13.5 ft) wide door in the aft left side of the aircraft's fuselage that could be opened in-flight to give the telescope access to the sky. The telescope was mounted in the aft end of the fuselage behind a pressurized bulkhead. The telescope's focal point is located at a science instruments suite in the pressurized, center section of the fuselage, requiring part of the telescope to pass through the pressure bulkhead. In the center of the aircraft was the mission control and science operations section, while the forward section hosts the education and public outreach area. The open fuselage has no significant influence on the aerodynamics and flight qualities of the airplane.[17]

At NASA's invitation, Lindbergh's grandson, Erik Lindbergh, re-christened the aircraft as Clipper Lindbergh, on May 21, 2007, the 80th anniversary of the completion of Charles Lindbergh's trans-Atlantic flight.[18]

During December 2012 the aircraft received a glass cockpit flight-deck upgrade along with new avionics systems and software updates.[19]

On April 28, 2022, the project announced it was retiring the aircraft as of September 30, 2022. Its 921st and last mission was over the North Pacific Ocean off the coast of California, taking off from Palmdale and returning there to land 7 hours and 57 minutes later at 04:41 PDT (11:41 UTC).[20][21][22]

The final flight of the aircraft occurred on December 13, 2022, when the aircraft departed from Palmdale and landed at Davis–Monthan Air Force Base, to be donated to the Pima Air & Space Museum located near Tucson, Arizona, where it has been placed on display.[23][24][25]

Project development

[edit]

The first use of an aircraft for performing infrared observations was in 1965 when Gerard P. Kuiper used NASA's Galileo Airborne Observatory to study Venus. Three years later, Frank J. Low used the Ames Learjet Observatory for observations of Jupiter and nebulae.[26] In 1969, planning began for mounting a 910 mm (36 in) telescope on an airborne platform. The goal was to perform astronomy from the stratosphere, where there was a much lower optical depth from water-vapor-absorbed infrared radiation. This project, named the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, was dedicated on May 21, 1975. The telescope was instrumental in numerous scientific studies, including the discovery of the ring system around the planet Uranus.[27]

The proposal for a larger aircraft-mounted telescope was officially presented in 1984 and called for a Boeing 747 to carry a three-meter telescope. The preliminary system concept was published in 1987 in a Red Book. It was agreed that Germany would contribute 20% of the total cost and provide the telescope. However, the reunification of Germany and budget cuts at NASA led to a five-year slide in the project. NASA then contracted the work out to the Universities Space Research Association (USRA), and in 1996, NASA and the German Aerospace Center (DLR) signed a memorandum of understanding to build and operate SOFIA.[28]

The SOFIA telescope's primary mirror was 2.5 meters in diameter and was manufactured of Zerodur, a glass-ceramic composite produced by Schott AG that has almost zero thermal expansion. REOSC, the optical department of the SAGEM Group in France, reduced the weight by milling honeycomb-shaped pockets out of the back. They finished polishing the mirror on December 14, 1999, achieving an accuracy of 8.5 nanometres (nm) over the optical surface.[29] The hyperbola-shaped secondary mirror was made of silicon carbide, with polishing completed by May 2000.[4] During 2002, the main components of the telescope were assembled in Augsburg, Germany. These consisted of the primary mirror assembly, the main optical support and the suspension assembly. After successful integration tests were made to check the system, the components were shipped to Waco, Texas on board an Airbus Beluga aircraft. They arrived on September 4, 2002.[30] SOFIA completed its first ground-based "on-sky" test on August 18–19, 2004 by taking an image of the star Polaris.[31]

The project was further delayed in 2001 when three subcontractors tasked with development of the telescope door went out of business in succession. United Airlines also entered bankruptcy protection and withdrew from the project as operator of the aircraft. The telescope was transported from Germany to the United States where it was installed in the airframe in 2004 and initial observations were made from the ground.[7]

In February 2006, after cost increases from $185 million to $330 million,[32] NASA placed the project "under review" and suspended funding by removing the project from its budget. On June 15, 2006, SOFIA passed the review when NASA concluded that there were no insurmountable technical or programmatic challenges to the continued development of SOFIA.[33][34]

The maiden flight of SOFIA took place on April 26, 2007, at the L-3 Integrated Systems' (L-3 IS) Waco, Texas facility.[35] After a brief test program in Waco to partially expand the flight envelope and perform post-maintenance checks, the aircraft was moved on May 31, 2007, to NASA's Armstrong Flight Research Center at Edwards Air Force Base. The first phase of loads and flight testing was used to check the aircraft characteristics with the external telescope cavity door closed. This phase was successfully completed by January 2008 at NASA- Armstrong Flight Research Center.[36]

On December 18, 2009, the SOFIA aircraft performed the first test flight in which the telescope door was fully opened. This phase lasted for two minutes of the 79-minute flight. SOFIA's telescope saw first light on May 26, 2010, returning images showing M82's core and heat from Jupiter's formation escaping through its cloud cover.[37] Initial "routine" science observation flights began in December 2010[13] and the observatory was slated for full capability by 2014 with about 100 flights per year.[7][36]

Since 2011, SOFIA missions were chosen amongst several proposals. Successful missions were scheduled according to yearly cycles, with the first cycle corresponding to 2013. During each cycle, the aircraft and instruments were shared between a few different missions.[38]

The astrophysics decadal survey for the 2020s recommended that NASA end SOFIA operations by 2023. "The survey committee has significant concerns about SOFIA, given its high cost and modest scientific productivity," the report stated.[39]

-

KAO and SOFIA, Ames Research Center 2008.

-

An F/A-18 mission support aircraft shadows SOFIA during a functional check flight.

-

The HAWC+ instrument mounted to the SOFIA telescope.

-

SOFIA Primary Mirror Assembly (PMA)

Scientific research and observations

[edit]The primary science objectives of SOFIA were to study the composition of planetary atmospheres and surfaces; to investigate the structure, evolution and composition of comets; to determine the physics and chemistry of the interstellar medium; and to explore the formation of stars and other stellar objects. While SOFIA aircraft operations were managed by the NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center in Palmdale, California, the NASA Ames Research Center in Mountain View, California, was home to the SOFIA Science Center which managed mission planning for the program.[7] On June 29, 2015, the dwarf planet Pluto passed between a distant star and the Earth producing a shadow on the Earth near New Zealand that allowed SOFIA to study the atmosphere of Pluto.[40]

In early 2016, SOFIA detected atomic oxygen in the Atmosphere of Mars for the first time in 40 years.[41] In early 2017, its observations of 1 Ceres in the mid-infrared helped determine the large asteroid/dwarf planet was coated with a layer of asteroid dust from other bodies.[42] In July 2017, SOFIA observed a star occultation of the distant Kuiper belt object 486958 Arrokoth while ground based observatories failed this observation, preparing the probe New Horizons visiting this asteroid.

Sofia has been used also for Astrobiology missions, focusing amongst other goals on the observation of new planetary systems and the detection of complex molecules.[43]

In October 2020, astronomers reported detecting molecular water on the sunlit surface of the Moon by several independent spacecraft, including the Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA).[44][45][46][47]

Between January and May of 2022, using the FORCAST instrument aboard SOFIA, the detection of water on asteroids was performed for the first time. The discovery was described in a paper published in February 2024.[48]

Airborne Astronomy Ambassadors Program (AAA)

[edit]SOFIA was designed from the beginning to support a robust public education and outreach effort that can, during the planned 20-year mission lifetime, directly involve more than a thousand educators of all types — K-12 teachers, science museum and planetarium educators, and public outreach specialists — as partners with the scientist, and reach hundreds of thousands of people across the nation through these educators.[49]

The "SOFIA Six" were the first set of educators selected in the United States to participate in SOFIA's AAA "Pilot" program, and flew during the summer of 2011. Germany had a separate application process, but also flew two teachers that summer.[50] Educator teams plus alternates were selected in a highly competitive application process. NASA and DLR (German Space Agency) selected educators who came from a variety of backgrounds, and their institutions included a school for the deaf, an alternative education site (developmentally challenged), highly underserved student populations, rural schools, and a Native American school. Since the "Pilot" cycle the AAA program has flown over 20 teams and was now in its Cycle 5 phase.[49][51]

Star Trek actress Nichelle Nichols flew aboard SOFIA on September 17, 2015.[52]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "SOFIA Science Center". Universities Space Research Association. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ Reinacher, Andreas; Graf, Friederike; Greiner, Benjamin; et al. (2018). "The SOFIA Telescope in Full Operation". Journal of Astronomical Instrumentation. 7 (4): 1840007. Bibcode:2018JAI.....740007R. doi:10.1142/S225117171840007X. S2CID 126242974.

- ^ Malacara, Daniel; Thompson, Brian J. (2001). Handbook of Optical Engineering. CRC Press. p. 246. ISBN 0-8247-9960-7.

- ^ a b c Krabbe, Alfred (March 2007). "SOFIA telescope". Proceedings of SPIE: Astronomical Telescopes and Instrumentation. Munich, Germany: SPIE — The International Society for Optical Engineering. pp. 276–281. arXiv:astro-ph/0004253. Bibcode:2000SPIE.4014..276K. doi:10.1117/12.389103.

- ^ Krabbe, Alfred; Casey, Sean C. (July 2002). "First Light SOFIA Instruments". Proceedings, SPIE conference on Infrared Spaceborne Remote Sensing X. Seattle, USA: Dordrecht, D. Reidel Publishing Co. arXiv:astro-ph/0207417. Bibcode:2002astro.ph..7417K.

- ^ "NASA – NASA Selects Science Instrument Upgrade for Flying Observatory". Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved April 17, 2012.

- ^ a b c d Keller, Luke; Jurgen Wolf (October 2010). "NASA's New Airborne Observatory". Sky and Telescope. 120 (4): 22–28. Bibcode:2010S&T...120d..22K.

- ^ "New Facility to Improve Airborne Telescope's Clarity". NASA.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "N747NA". Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ "N747NA". Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ a b c "Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy 308911 SOFIA Quick Facts" (PDF). nasa.gov. National Aeronautics and Space Administration. 2010. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 28, 2009. Retrieved December 2, 2010.

Manufacturer's serial number:21441 Line number:306

- ^ Kulkarni, Sumeet (September 28, 2022). "SOFIA: NASA's flying infrared observatory prepares for its final take-off". Astrobites. Retrieved September 29, 2022.

- ^ a b "News and Updates". Archived from the original on April 3, 2012.

- ^ "The Boeing 747 Classics". boeing.com. The Boeing Co. Archived from the original on November 21, 2010. Retrieved January 23, 2009.

Boeing also built the 747-100SP (special performance), which had a shortened fuselage and was designed to fly higher, faster and farther non-stop than any 747 model of its time.

- ^ a b "History for airframe #21441". 747sp.com. 2010. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

2/13/1986 N536PA United Bought

- ^ "21023 / 268 - Production List". Boeing 747SP Website. July 21, 2022. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Beall, Ace (December 8, 2015). "Omega Tau Podcast Episode 190 – SOFIA Part 2, The Flights" (Interview). Interviewed by Markus Völter. Omega Tau Podcast.

- ^ Hautaluoma, Grey; Hagenauer, Beth (May 11, 2007). "NASA's SOFIA to be Rededicated on Historic Lindbergh Anniversary". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Archived from the original on November 24, 2010. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "SOFIA Upgrades: Integrating Telescope Onboard Command and Control Systems". nasa.gov. www.nasa.gov. December 3, 2012. Archived from the original on June 17, 2019.

- ^ "NASA, Partner Decide to Conclude SOFIA Mission". NASA. April 28, 2022. Retrieved October 29, 2022.

- ^ Zurbuchen, Thomas [@Dr_ThomasZ] (September 28, 2022). "The @SOFIAtelescope just embarked on its last flight. On behalf of our team, I am grateful to the dedicated scientists and engineers, including many from @DLR_en, who have contributed important science results and have done so safely. Follow along at https://flightaware.com/live/flight/NASA747" (Tweet). Retrieved October 30, 2022 – via Twitter.

- ^ "NASA747 National Aeronautics and Space Administration Flight Tracking and History 28-Sep-2022 (KPMD-KPMD)". FlightAware. September 29, 2022. Retrieved October 30, 2022.

- ^ "Boeing 747SP "SOFIA"". Pima Air & Space Museum. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Fisher, Alise (December 8, 2022). "NASA's Retired SOFIA Aircraft Finds New Home at Arizona Museum". NASA. Retrieved December 12, 2022.

- ^ "N747NA Flight Tracking and History". FlightAware. Retrieved February 24, 2024.

- ^ Erickson, E. F.; Davidson, J. A. (July 1994). "SOFIA: The future of airborne astronomy". Proceedings of the Airborne Astronomy Symposium on the Galactic Ecosystem: From Gas to Stars to Dust. Mountain View, CA: Astronomical Society of the Pacific. pp. 707–773. Bibcode:1976IAUS...73...75P.

- ^ Mewhinney, Mike (May 24, 2005). "Kuiper Airborne Observatory Marks 30th Anniversary of its Dedication". NASA. Retrieved July 4, 2008.

- ^ Titz, Ruth; Roeser, Hans-Peter (1998). SOFIA : astronomy and technology in the 21st century. Vol. 12. Berlin: Wissenschaft und Technik. p. 107. arXiv:astro-ph/9908345. Bibcode:1999RvMA...12..107K. ISBN 3-89685-558-1.

- ^ Staff (December 14, 1999). "REOSC Delivers the Best Astronomical Mirror in the World to ESO". European Southern Observatory. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ Casey, Sean C. (2004). "The SOFIA program: astronomers return to the stratosphere". Advances in Space Research. 34 (3): 77–115. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..34..560C. doi:10.1016/j.asr.2003.05.026.

- ^ Mewhinney, Michael (September 9, 2004). "NASA Airborne Observatory Sees Stars For First Time". SOFIA Science Center. Archived from the original on October 12, 2006. Retrieved July 23, 2003.

- ^ McKee, Maggie (February 13, 2006). "NASA leaves jumbo-jet telescope on the runway". NewScientist.com.

- ^ "NASA Astronomical Observatory Passes Hurdle". June 15, 2006. Archived from the original on November 26, 2020. Retrieved August 9, 2006. NASA Headquarters press release 06-240

- ^ Berger, Brian (May 30, 2006). "NASA Expected To Save SOFIA". Space News Business Report. Archived from the original on April 20, 2007.

- ^ Martin, Lance; Backman, Dana (April 26, 2007). "SOFIA Airborne Observatory Completes First Test Flight". SOFIA Science Center. Archived from the original on November 22, 2008. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ a b Hautaluoma, Grey; Hagenauer, Beth (January 16, 2008). "SOFIA Completes Closed-Door Test Flights". NASA. Archived from the original on April 6, 2013. Retrieved July 23, 2008.

- ^ "SOFIA Sees Jupiter's Ancient Heat". Seeker.com. DNews. May 29, 2010.

- ^ "Cycle 7 Current Schedule and Flight Plans". SOFIA Science Center. Universities Space Research Association.

- ^ "Astrophysics decadal survey recommends NASA terminate SOFIA". SpaceNews. November 13, 2021. Retrieved August 28, 2022.

- ^ Veronico, Nicholas A.; Squires, Kate K. (June 29, 2015). "SOFIA in the Right Place at the Right Time for Pluto Observations". NASA. Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- ^ Bell, Kassandra (May 6, 2016). "Flying Observatory Detects Atomic Oxygen in Martian Atmosphere". NASA. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Veronico, Nicholas A. (January 19, 2016). "Don't Judge an Asteroid by its Cover: Mid-infrared Data from SOFIA Shows Ceres' True Composition". NASA. Archived from the original on January 25, 2019. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Voytek, Mary A. (November 15, 2019). "SOFIA missions astrobiology". NASA. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- ^ Honniball, C.I.; et al. (October 26, 2020). "Molecular water detected on the sunlit Moon by SOFIA". Nature Astronomy. 5 (2): 121–127. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-01222-x. S2CID 228954129. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Hayne, P.O.; et al. (October 26, 2020). "Micro cold traps on the Moon". Nature Astronomy. 5 (2): 169–175. doi:10.1038/s41550-020-1198-9. S2CID 218595642. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Guarino, Ben; Achenbach, Joel (October 26, 2020). "Pair of studies confirm there is water on the moon – New research confirms what scientists had theorized for years — the moon is wet". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (October 26, 2020). "There's Water and Ice on the Moon, and in More Places Than NASA Once Thought – Future astronauts seeking water on the moon may not need to go into the most treacherous craters in its polar regions to find it". The New York Times. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Detection of Molecular H2O on Nominally Anhydrous Asteroids".

- ^ a b "Airborne Astronomy Ambassadors". SOFIA Science Center. Universities Science Research Association. Archived from the original on March 27, 2014.

- ^ "News and Updates". Archived from the original on August 5, 2012.

- ^ "SOFIA Science Newsletter". SOFIA Science Center. April 2017. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth (August 6, 2016). "Nichelle Nichols, Star Trek's 'Uhura,' Will Fly on NASA's SOFIA Observatory". Space.com. Retrieved April 26, 2018.

External links

[edit]- SOFIA Science Center, USRA & DSI

- SOFIA mission, NASA

- SOFIA Mission Profile by Solar System Exploration at NASA

- DLR's SOFIA Website Archived April 2, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: SOFIA's Window Seat (February 25, 2006)

- Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at University of Chicago

- SOFIA: Stratospheric Observatory For Infrared Astronomy, Moonfest 2009 by NASA