History of Florida State University

The history of Florida State University dates to the 19th century and is deeply intertwined with the history of education in the state of Florida and in the city of Tallahassee. Florida State University, known colloquially as Florida State and FSU, is one of the oldest and largest of the institutions in the State University System of Florida.[1] It traces its origins to the West Florida Seminary, one of two state-funded seminaries the Florida Legislature voted to establish in 1851.[2]

The West Florida Seminary, also known as the Florida State Seminary,[3] opened for classes in Tallahassee in 1857, absorbing the Florida Institute, which had been established as an inducement for the state to place the seminary in the city.[4] The former Florida Institute property, located where the historic Westcott Building now stands, is the oldest continuously used site of higher education in Florida. The area, slightly west of the state Capitol, was formerly and ominously known as Gallows Hill, a place for public executions in early Tallahassee.[1][5] In 1858 the seminary absorbed the Tallahassee Female Academy, established in 1843, and became coeducational.[6]

In 1863, during the American Civil War, Florida's Confederate government added a military school to the institution, and changed its name to the Florida Military and Collegiate Institute. The school fielded student soldiers into an organized unit of the institution, which helped successfully repel a Union attack on Tallahassee at the Battle of Natural Bridge.[7] In 1883, it became part of the Florida University, the first state-supported university to be founded in Florida.[8] The university project struggled with a lack of legislative support, and the seminary soon returned to its old name, but focused increasingly on modern-style secondary education. In 1905 the Buckman Act restructured higher education in Florida, and the school was reorganized as a college for white women, the Florida State College for Women. After World War II, the school was made coeducational once again to help accommodate the influx of students entering college under the G.I. Bill, and was renamed Florida State University. It became racially integrated in 1963, and was noted as a center of student activism during the 1960s. Through the 20th and 21st centuries Florida State University has grown in both size and academic prominence, with a particular focus on graduate and doctoral research.

Founding

[edit]

In 1823 the United States Congress determined that the Florida Territory shall receive two seminaries of learning, one on each side of the Suwannee River.[9] By 1838, the first constitution of the Florida Territory embraced and permanently guaranteed a system of general education (schools) and higher education (seminaries).[10]

Throughout the history of Tallahassee strong energy and focus toward education originated with leaders and members of the First Presbyterian Church, Tallahassee, located near Florida State University. The First Presbyterian Church building was built before 1838 and is the oldest public building in Tallahassee.[11] For almost a century the First Presbyterian Church of Tallahassee would have a strong symbiotic relationship with the origin and development of the educational institution known today as Florida State University.[12]

Leon Academy (1827-1840)

[edit]City officials of Tallahassee took steps to establish a school for boys as early as 1827 with the establishment of the Leon Academy.[13] Leon Academy was advertised in the Pensacola Gazette of March 9, 1827 as being under the supervision of Presbyterian Rev. Henry M. White, A.M.[14] By early 1831 the Leon Academy was under the control of the Tallahassee City Council.[15]

Leon Academy was incorporated by an act of the Territorial Legislative Council on February 12, 1831 under the control of seven trustees.[16] The Leon Academy suffered from lack of financial resources as well as high administrative turnover and in September 1836 was operated by John M. Brook of Virginia as a "private Seminary for boys", while the trustees continued to control and manage the property.[14] By 1840 the Leon Academy ceased operations as a public school.[14] The trustees, however, turned to the Territorial Legislature once again, who passed an "Act in Relation to the Trustees of Leon Academy" in 1840 wherein the Treasurer of the Territory was directed to pay funds to the trustees to "assist said Trustees in building an Academy".[17] On March 9, 1840 the Leon Academy had been refreshed with some Territory support.[18] The trustees solicited Territory support on the basis the Leon Academy would serve both male and female students.[14] There is disagreement among scholars if the male-only Leon Academy is the forerunner of the West Florida Seminary.[18][19] A point of agreement between the scholars is that the same leading citizens of Tallahassee were interested in both institutions.[14]

Leon Academy for Males and Females, Florida Institute, Florida Seminary (1846-1891)

[edit]Leon Academy was replaced by schools for males and females in a system established by Reverend Joshua Phelps and Elder David C. Wilson, both of the First Presbyterian Church. Princeton University-educated Reverend William Neil and his wife Eliza Neil operated the academies for males and females, which were merged in 1846 into a new version of the Leon Academy for Males and Females. The Leon Academy later split into the Tallahassee Female Academy, also known as the Leon Female Academy for females. While organized public education for males faltered between 1840 and 1850, education for females was intact and unusually complete. By January 1850 municipal elections in Tallahassee called for a city-supported school for males and the Tallahassee City Council, assumed financial responsibility for the Florida Institute the same year.

On January 24, 1851 the Florida Legislature voted to establish West Florida Seminary, which became Florida State University and East Florida Seminary which became the University of Florida.[20] The 1851 law specified the organization and governing boards of the schools, including terms of office for those boards, and specified the nature and scope of instruction at each institution. This law effectively established the joint charter for the two seminaries, providing for their complete operation.[21] It did not decide locations for the schools, however, leaving this to be awarded to the jurisdictions with the best offer of support.[22]

The Legislature concluded in Resolution No. 25 of that year that each seminary would be awarded to the county or town that would provide the best combination of land, buildings and money. Three towns presented offers for the West Florida Seminary - Tallahassee, Marianna and Quincy. The competition between the three soon became a bitter struggle between Marianna and Tallahassee for the West Florida Seminary. By January 1853 the Legislature accepted Ocala's offer for the East Seminary and in the same law directed Governor James E. Broome to appoint a special commission of six members from Middle and West Florida to decide upon the location of the West Seminary. The matter had grown so contentious that neither Governor Broome nor the Commission members looked forward to the task and did little to resolve the contest. The issue was then handed back to the Legislature where it was finally confronted. In the meantime, as an inducement to the Legislature, the City Council of Tallahassee had built and funded an all-male academy, called the Florida Institute, in Tallahassee.[23] The Florida Institute was a resurrected version of the Leon Academy established in 1827 by Presbyterian Reverend Henry White.[24]

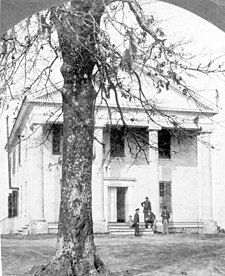

The subsequent law of 1851 establishing the Seminaries seemed an answer to the existing educational needs of Tallahassee when it passed the Legislature. In 1854, the Tallahassee City Council offered to pay $10,000 to finance a new school building on land owned by the city in an attempt to "bid on" being the location of the seminary west of the Suwannee River. Later in 1854, construction on a school building began and Tallahassee’s city intendent (W.R. Hayward) approached the state legislature to present the case for the seminary to be in Tallahassee. However, state officials failed to make a decision regarding the location of the seminary before the end of the legislative session. The building of the Florida Institute was regarded at the time as the "handsomest edifice in Tallahassee" and cost $6,172.00 at its completion in April 1855. Around 100 students enrolled in the school year 1855-1856.[25] A group of citizens calling themselves the "friends of the Institution" planned to petition the Legislature to create the University of Florida from the Florida Institute.[26] By 1856, the Tallahassee City Council had "bid on" being the location of the Seminary once again and, this time, had won. The intendent was F.W. Eppes. The Florida Institute became the West Florida Seminary. The rise of land slightly west of the center of Tallahassee, formerly known as Gallows Hill, which was the site and building of the ongoing Florida Institute, was offered and accepted as the western state seminary for male students. The seminary officially held classes as a state institution in 1857. In 1858 it absorbed the Tallahassee Female Academy begun in 1843 as the Misses Bates School, thereby becoming co-educational.[27] The West Florida Seminary stood near the front of the Westcott Building on the existing FSU campus.[28] This site is the oldest continually used location of higher learning in Florida.[29][30] The eastern seminary was located in Ocala in 1853 and closed during the American Civil War. It reopened in 1866 in Gainesville and would eventually be combined with other schools to form what would be called the University of the State of Florida in 1906.[31]

Civil War and Reconstruction

[edit]

During the American Civil War the name of the seminary was changed to The Florida Military and Collegiate Institute and began military training for students. Young cadets from the school, along with other soldiers from Tallahassee, defeated Union forces at the Battle of Natural Bridge in 1865.[7][32] The students were trained by Valentine Mason Johnson, a graduate of Virginia Military Institute, who was a professor of mathematics and the chief administrator of the college.[33] By the end of the war Tallahassee was the only Confederate capital east of the Mississippi River not to fall to Union forces.[34]

The Army Reserve Officers' Training Corps unit at Florida State University is one of only four ROTC units in the United States with permission to display a campaign streamer.[35] The streamer reads NATURAL BRIDGE 1865. After the fall of the Confederacy, campus buildings were occupied by Union forces for over a month. The West Florida Seminary reverted to a purely academic purpose after the war, and began a period of substantial growth and development.

First state university (1883-1901)

[edit]In 1883 West Florida Seminary became part of Florida University, Florida's first state-sponsored university.[36] In January 1883 Reverend John Kost, A.M., M.D., LL.D of Michigan proposed to carry out the mandate of the 1868 Constitution requiring a state university. Kost secured a charter from Governor William D. Bloxham that merged West Florida Seminary and the Tallahassee College of Medicine and Surgery into a new institution known as Florida University.[8] The West Florida Seminary became the institution's Literary College, and was to contain several "schools" or departments in different disciplines.[36] However, in the new association the seminary's "separate Charter and special organization" were maintained.[37] The charter also recognized three further colleges to be established at a later time: a Law College, a Theological Institute, and a Polytechnic and Normal Institute.[37]

The Florida Legislature recognized the university under the title "University of Florida" in Spring 1885, but committed no additional financing or support.[38] Without legislative support, the university project struggled, and the association dissolved when the medical college relocated to Jacksonville later that year.[36] The Law Department was discontinued at the same time.[39]: 122–123 The Florida Agricultural College in Lake City tried to revive interest in the university plan, announcing its desire to merge with the University of Florida in 1886 and 1887; however, nothing came of this at the time.[38] By 1891, however, President Edgar had developed a four-year curriculum and a collegiate organization with freshmen, sophomore, junior and senior ranks. The school's first Commencement, under the name Florida State University, took place from June 10–12, 1891.[40] The Tallahassee institution never assumed the "University of Florida" name,[38] though the act recognizing it as such was not repealed until 1903, when the title was transferred to the Florida Agricultural College.[38][41]

The West Florida Seminary, as it was still generally called, continued to expand and thrive. It shifted its focus increasingly towards modern-style post-secondary education, awarding "Licentiates of Instruction" – its first diplomas – in 1884, and awarding Bachelor of Arts degrees in 1891.[42] It had become Florida's first liberal arts college by 1897.

Florida State College (1901–1905)

[edit]

In 1901 the Seminary was reorganized into the Florida State College, with four departments: the College, the College Academy, the School for Teachers and the School of Music.[42] President was Albert Alexander Murphree.[43]: 89 Its aspiration was "to be not only the foremost school of this State, but to be classed in the first rank of the colleges of the South."[39]: 7 In 1901–1902 there were "nearly 300 Bona Fide Students from Twenty-Eight Florida Counties and Six States".[43]: 115 It awarded the B.A. degree, emphasizing Greek and Latin, the B.Sc. Degree, emphasizing modern languages and physical sciences, and the B.L. degree, emphasizing English, German, and the Romance languages.[43]: 115 According to its yearbook The Argo, It had track, baseball, and football teams;[43]: 72–78 in 1902 a women's basketball team was added.[43]: 96–97 In the Normal School, established "three years ago, seeing the sad condition of our public schools", enrollment was 90, from "almost every county in the state".[39]: 37

Florida State College for Women (1905–1947)

[edit]

The 1905 Buckman Act reorganized the existing six Florida colleges into three institutions, segregated by "race" and gender—a school for white males (University of Florida), a school for white females (Florida Female College), and a school for both African American males and females (State Normal School for Colored Students).[44] By 1909, the name was again changed to the Florida State College for Women after the initial title was generally rejected.

Under the Buckman Act the State Normal School for Colored Students (now Florida A&M University) became the college serving African Americans, while the state's other four institutions (the University of Florida at Lake City (formerly Florida Agricultural College), the East Florida Seminary in Gainesville, the St. Petersburg Normal and Industrial School in St. Petersburg, and the South Florida Military College in Bartow) were merged into a school for white males known as the University of the State of Florida, located in Gainesville. The Buckman bill was the brainchild of Henry Holland Buckman, a legislator from Duval County, Florida. It was hotly debated, with one legislator saying in debate: "I believe in coeducation. Statistics prove satisfactory to me that separate institutions for male and female is detrimental (sic) to both--physically, mentally and morally."[45] Further, according to Shira Birnbaum, the Buckman Act:

...didn't merely standardize, consolidate and narrow opportunities for public higher education in Florida. It also inaugurated an era of new school gender practices. Right from the start, in fact, the Buckman Act's message to Florida's women was that the highest levels of educational attainment--the advanced degrees and professional schools of a "university education"--would be reserved for white males attending the new all-male University of the State of Florida. White women, by contrast, had to settle for a "college." Furthermore, the Buckman Act mandated that the university would "teach...the fundamental laws and...the rights and duties of citizens ..." to its male students. The college, by contrast, would "teach...all the useful arts and sciences that may be necessary or appropriate." A dual discourse had been laid out--one that framed education for white men as a matter of "citizenship" and education for white women as a matter of "usefulness".[46]

A residence hall currently on the campus of the University of Florida bears the name Buckman Hall in honor of the legislator. No equivalent building to date exists on the campus of Florida State University.[47]

Despite the impact of the Buckman Act, Albert A. Murphree, then President of the Florida State College, determined to stress liberal studies and academic performance.[48] Florida State was the largest of the original two universities in Florida, even during the period as the college for women (1905 to 1947) until 1919.[49] By 1933, the Florida State College for Women had grown to be the third largest women’s college in the United States.[50] In 1935, the College was awarded the Alpha chapter of Phi Beta Kappa in Florida.[51][52] The Florida State College for Women was the first state women's college in the South to be awarded a chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, as well as the first university in Florida to be so honored for academic quality.[53]

World War II changes (1945-1960)

[edit]After World War II, returning soldiers taking advantage of the new G.I. Bill placed an unexpectedly heavy demand on the state university system. The Tallahassee Branch of the University of Florida (TBUF) was quickly opened on the campus of the Florida State College for Women.[42][54] The men were housed in former barracks on Dale Mabry Field, an existing WWII U.S. Army Air Force training field west of Tallahassee, that was deactivated in part after the war. Male students were then enrolled into the Florida State College for Women and traveled to the main campus by bus. Part of Dale Mabry Field became known as "West Campus" during this brief period. By the end of the 1946-1947 school year, 954 men were enrolled in the TBUF program. By 1947 the Florida Legislature returned the FSCW to coeducational status and renamed the Florida State College for Women the Florida State University.[55] The FSU West Campus land and barracks plus other areas continually used as an airport later became the location of the Tallahassee Community College.

The 1950s brought substantial growth and development to the university. Several colleges were added and the first Ph.D. was awarded in Chemistry by 1952.[citation needed] Many buildings recognizable today[when?] were added to the university such as the Strozier Library, Tully Gymnasium and the original parts of the Business building.[citation needed] Programs supplementing the original liberal arts and education departments were added including Business, Journalism discontinued in 1959, Library Science, Nursing and Social Welfare. [citation needed] Social Welfare was later split into the College of Criminology and the College of Social Work.[citation needed]

Hymns

[edit]"The Hymn to the Garnet and the Gold" was originally written by J. Dayton Smith for chorus and was first premiered by the Collegians, the male chorus attached to the School of Music, at the 1950 Homecoming. In 1958, Charlie Carter arranged the piece for the Marching Chiefs and it was performed as the closer to the Homecoming show, cementing it as a Homecoming tradition at Florida State.[56]

The 1950 Homecoming half-time show included a dedication ceremony naming the stadium in honor of university President Doak Campbell. There was also a special performance by the band, christening it the Marching Chiefs and premiering the "FSU Fight Song." Student Doug Alley wrote the lyrics to the fight song as a poem which first appeared in the Florida Flambeau. Professor of music Thomas Wright saw the poem in the newspaper and wrote a melody to it as he was inspired by the surge of school spirit.[57]

Thomas Wright grants rights to the song in exchange for two season tickets every year.[58][59]

Fifty years later, the FSU Fight Song is one of the most widely recognized college tunes in the country. Mission Control used the Fight Song to awaken alumnus and current professor Norm Thagard one morning in 1983 while he was aboard the Challenger spacecraft.[60]

Student activism and racial integration

[edit]

During the 1960s and 1970s, Florida State University was known as a center of student activism especially in the areas of racial integration, women's rights and the Vietnam War. The school acquired the nickname 'Berkeley of the South'[61] during this period, in reference to similar student activities at the University of California, Berkeley and is also purported to be the site of the genesis of "streaking," which is said to have first been observed on Landis Green.[62][63][better source needed] Governor Claude Kirk appeared unexpectedly one morning with a chair and spent the day, with little escort or fanfare, on Landis Green discussing politics with protesting students. Elements of free speech activism still exist at FSU today. The Center for Participant Education was established in 1970 as an alternative to traditional university academics. Its purpose is to allow students to "explore socially relevant topics and to foster a healthier philosophy of education through classes in which anyone could teach or attend. Its first catalog was designed by FSU student James Clement van Pelt, who founded the Miccosukee Land Co-op in Tallahassee three years later with other FSU students and faculty. Since then, CPE has been investigated by the Legislature, suspended by the Board of Regents, and challenged by FSU administration. CPE has managed to hold strong through all of this, and remains today as one of the last free universities in the country."[64] Florida State also established the Institute of Molecular Biophysics, Space Biosciences and the Programs in Medical Studies.

After many years as a segregated university, and partly due to the efforts of students starting in the late 1950s (including sit-ins and an application to attend Florida A&M University by FSU student Alan Breitler in 1960,[65]) in 1962 Maxwell Courtney became the first African American undergraduate student admitted to Florida State.[66] In 1968 Calvin Patterson became the first African American player for the Florida State University football team.[67]

Tallahassee and Florida State were difficult places for African Americans even as late as 1968. When Calvin Patterson, a star player from Miami, signed with the Florida State Seminoles he endured insults and threats from the beginning. Tallahassee, at the time, was very much still rooted in the Old South as Patterson was neither accepted by many white students and fans at FSU nor the black students at nearby historically black Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University who viewed Patterson as a traitor.[67]

A 2017 study by The Education Trust, examining data from 2014, found that Florida State University ranked in the top 20 colleges in the country in graduation rates among African-American students. About 75% of African-American students (who make up 8.4% of FSU students) graduate within six years, compared to a national average of 40%.[68]

Pathways of Excellence

[edit]The strategic vision of Florida State University, known as Pathways of Excellence, changed in September 2005 as the result of an evaluation of "FSU’s academic productivity and recognition as viewed in the context of the Phase I and Phase II indicators for membership in the Association of American Universities (AAU) and the standards used by the National Research Council for evaluating doctoral programs."[69] The task group made recommendations, on which FSU President Wetherell acted, which are intended to transform the overall academic quality and scholarly productivity of the university. The faculty group created specific goals for the university which include investment in new university faculty hired in "academic clusters"[70] focused principally on doctoral-level research. Coupled with this investment in 200 new faculty members is an expansion of the physical infrastructure of the university.[71] To date, new construction is underway or recently completed for a new Experimental Social Science Laboratory, a College of Medicine Research Building, a new Psychology Building, a new Chemistry Building, a new Life Sciences Teaching and Research Building and a new Materials Research Building.

Concurrently, other existing research facilities at the university have been renovated, including the Nancy Smith Fichter Dance Theatre, the Kasha Laboratory of the Institute of Molecular Biophysics plus enhancements to the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory and a new Applied Superconductivity Center.

2014 shooting

[edit]On November 20, 2014, a gunman armed with a .380 semiautomic pistol, identified as 31-year-old Myron May, shot an employee and two students at Strozier Library on the university campus shortly after midnight. He was a lawyer, former prosecutor and an alumnus of the university. He sent a message to a friend "I do not want to die in vain" as he feared that U.S. government "stalkers" were using a "direct energy weapon" to hurt him. His social media indicated that he was one of a number of people driven to violence who believed he was a "targeted individual" attacked by mind control and invisible weapons. He was fatally shot by responding police officers after he began shooting at them outside Strozier Library. After the shooting, it was revealed that May had mailed a total of ten packages to friends throughout the country beforehand; the contents of the packages were harmless.[72][73][74]

See also

[edit]- Burning Spear Society

- Florida State Seminoles

- History of Florida

- List of Florida State University people

- List of presidents of Florida State University

References

[edit]- ^ a b Office of University Communications (September 23, 2009). "About Florida State: History". www.fsu.edu. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ "Early Education in Tallahassee and the West Florida Seminary now Florida State University - Part I by William G. Dodd, p.13, The Florida Historical Quarterly volume 27 issue 1 July 1948". Retrieved 2014-07-16.

- ^ Coles, David J. (1999). "Florida's Seed Corn: The History of the West Florida Seminary During the Civil War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 77 (3). Florida Historical Quarterly 77: 302. JSTOR 30147582.

- ^ "Early Education in Tallahassee and the West Florida Seminary now Florida State University - Part II by William G. Dodd, p.158-9, The Florida Historical Quarterly volume 27 issue 2 October 1948" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 February 2010. Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ Hare, Julianne (2002-05-01). Tallahassee - A Capital City History, p.42, Julianne Hare, Arcadia Publishing (May 1, 2002). ISBN 978-0-7385-2371-2. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Book Review: Gone with the Hickory Stick: School Days in Marion County 1845-1960, p.122, The Florida Historical Quarterly - Volume LV, Number 3 January 1977" (PDF). Retrieved July 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "Florida Timeline". Archived from the original on April 4, 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-09. State Library and Archives of Florida - The Florida Memory Project Timeline (see 1865) Retrieved on 4-29-2007

- ^ a b "Calendar of the Florida University - Organization". Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- ^ "p. 30, History of Education in Florida (George Gary Bush, Ph.D; Washington GPO 1889)". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-06-24. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) State Library and Archives of Florida - The Florida Memory Project, Florida Constitution of 1838, Article X - Education: "Section 1. The proceeds of all lands that have been or may hereafter be granted by the United States for the use of Schools, and a Seminary or Seminaries, of learning, shall be and remain a perpetual fund, the interest of which, together with all monies derived from any other source applicable to the same object, shall be inviolably appropriated to the use of Schools and Seminaries of learning respectively, and to no other purpose. Section 2. The General Assembly shall take such measures as may be necessary to preserve from waste or damage all land so granted and appropriated to the purposes of Education." Retrieved on 5-25-2007 - ^ "An Historical Sketch of the Sanctuary First Presbyterian Church Tallahassee". Archived from the original on 2008-01-16. Retrieved 2007-11-14. An Historical Sketch Of the Sanctuary First Presbyterian Church Tallahassee, Florida Retrieved on 2-10-2008.

- ^ At First - The Presbyterian Church in Tallahassee, Florida, 1828-1938 p. 111; Barbara Rhodes, Copyright 1994, First Presbyterian Church, Tallahassee, FL

- ^ "Early Education in Tallahassee and the West Florida Seminary now Florida State University - Part I by William G. Dodd, p.3, The Florida Historical Quarterly volume 27 issue 1 July 1948". Retrieved 2010-08-03.

- ^ a b c d e Dodd July 1948, supra

- ^ Dodd July 1948, p. 4.

- ^ Dodd July 1948, p. 5.

- ^ Dodd July 1948, p. 6.

- ^ a b Dodd July 1948, p. 7.

- ^ Knauss, James O.: Education in Florida 1821-1829, page 26. Florida Historical Quarterly volume 3, No.4, 1925.

- ^ "Florida Timeline". Archived from the original on 2007-04-04. Retrieved 2007-10-09. State Library and Archives of Florida - The Florida Memory Project Timeline (see 1851) Retrieved on 4-28-2007

- ^ Dodd, William George: History of West Florida Seminary, page 1. Florida State University, 1952.

- ^ Dodd 2005, p.1.

- ^ [1] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, Original building of the all-male Florida Institute, one predecessor of the West Florida Seminary. Archives metadata: The male academy. Built in 1854, by the city, as an inducement for the legislature to name Tallahassee as the site of the Seminary West of the Suwanee. Operated as the Florida Institute until it became West Florida Seminary in 1857. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ Dodd, William G. (1952). History of West Florida Seminary. Tallahassee: Florida State University. p. 10.

- ^ Dodd July 1948, p. 25.

- ^ Dodd July 1948, p. 26.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2007-04-28.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Florida State University Libraries - John L. DeMilly Papers 1877-1879, Historical Note Retrieved on 4-28-2007. - ^ [2] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, Map showing location of the West Florida Seminary published 1885. Archives metadata: No. 3 was the seminary. Built in 1854. In use 1857, when classes began, until 1891 when it was remolded to College Hall. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [3] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, West Florida Seminary c. 1884. Archives metadata: Building given to the seminary at its inception (1857) for classes. Destroyed in 1891 to make way for College Hall. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [4] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, College Hall at the West Florida Seminary c. 1898. Archives metadata: Constructed in 1891. Replaced by Westcott in 1909. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [5] Text adapted from _Historic Gainesville, A Tour Guide to the Past_, Ben Pickard, ed., Historic Gainesville, Inc., Gainesville, FL, 1991, 48 pp. Copyright by Historic Gainesville, Inc. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [6] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, West Florida Seminary Cadets, published c. 187-. Archive metadata: West Florida Seminary cadets taking a break Retrieved on 4-29-2007

- ^ "Valentine Mason Johnson - pugknows.com". Retrieved 2008-12-22.

- ^ "State Library and Archives of Florida, The Florida Memory Project - Timeline". 1865. Archived from the original on 2009-06-07. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- ^ The other three programs are: the Virginia Military Institute (VMI) for the Battle of New Market, The Citadel for the defense of Charleston and other engagements, and The University of Mississippi for the defense of Vicksburg.

- ^ a b c Bush, George Gary (1889). History of Education in Florida. Washington: Government Printing Office. pp. 46–47. Archived from the original on July 25, 2011. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b Constitutional Convention, Florida (June 9, 1885). Journal of the Proceedings of the Constitutional Convention of the State of Florida, p. 21. Harvard College Library. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Armstrong, Orland Kay (c. 1928). "The Life and Work of Dr. A. A. Murphree, p. 40". Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Florida State College". Argo. 3. Students of Florida State College. 1903.

- ^ Dodd, History of West Florida State Seminary, p.82

- ^ [7] History of Florida State University, Office of the Dean of the Faculties, September 5, 2001 - "The following quote from the 1903 Florida State College Catalogue adds an interesting footnote to this period: In 1883 the institution, now long officially known as the West Florida Seminary, was organized by the Board of Education as The Literary College of the University of Florida. Owing to lack of means for the support of this more ambitious project, and also owing to the fact that soon thereafter schools for technical training were established, this association soon dissolved. It remains to be remarked, however, that the legislative act passed in 1885, bestowing upon the institution the title of the University of Florida, has never been repealed. The more pretentious name is not assumed by the college owing to the fact that it does not wish to misrepresent its resources and purposes." Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "About Florida State - History". Office of University Communications. September 23, 2009. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "Florida State College". Argo. 2. Students of Florida State College. 1902.

- ^ [8] State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, Westcott Building at the Florida State College for Women, published 193-. Archives metadata: Fountain and Westcott Building at Florida State College for Women. Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [9] Shira Birnbaum, "Making Southern belles in progressive era Florida: Gender in the formal and hidden curriculum of the Florida Female College", p. 7, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2/3, Gender, Nations, and Nationalisms (1996), pp. 218-246 doi:10.2307/3346809 Retrieved on 7-02-2007.

- ^ [10] Shira Birnbaum, "Making Southern belles in progressive era Florida: Gender in the formal and hidden curriculum of the Florida Female College", p. 8, Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, Vol. 16, No. 2/3, Gender, Nations, and Nationalisms (1996), pp. 218-246 doi:10.2307/3346809 Retrieved on 7-02-2007.

- ^ [11] Florida State University - Campus Map Retrieved on 7-02-2007.

- ^ "Women and Science at FSU". Archived from the original on 2007-07-13. Retrieved 2007-07-03. Florida State University - Women and Science at FSU Retrieved on 7-02-2007.

- ^ "Florida Board of Governors SUS Headcount Enrollment - 1905-Present". Retrieved 2009-05-18.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Florida State University Libraries Special Collections Department, Inventory of the Florida State College for Women Surveys and Reports (MSS2003003), Biographical/Historical Notes. Created by Amy McDonald. Copyright Florida State University Libraries, 2004 Retrieved on 4-30-2007. - ^ "Alpha of Florida - Phi Beta Kappa". Archived from the original on 2004-08-14. Retrieved 2007-07-06. Alpha of Florida - Phi Beta Kappa Retrieved on 4-29-2007.

- ^ [12] Archived 2007-09-27 at the Wayback Machine Phi Beta Kappa - Chronology of Chapters Retrieved on 5-23-2007.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-03. Retrieved 2007-04-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Florida State University Libraries Special Collections Department, Inventory of the Florida State College for Women/Florida State University Phi Beta Kappa Alpha of Florida Chapter. (MSS2005-014) Biographical/Historical Notes. Created by Erin VanClay, Copyright Florida State University Libraries, 09/2005 Retrieved on 4-30-2007. - ^ Image:Tbuf rc01381.jpg State Library and Archives of Florida - Florida Photographic Collection, Tallahassee Branch of the University of Florida at the Florida State College for Women c. 1946. Archives metadata: The first 507 students went to register for the TBUF program, 1946-47. They were enrolled at Florida State College for Women in 1946. TBUF was created to serve men returning from World War II because there was no room at the state men's college, the University of Florida. They were the first men on campus since 1905. Retrieved on 4-30-2007.

- ^ [13] Personal history of Mary Lou Norwood, FSCW/FSU Alumna, (transitional) Class of 1947 (FSU webpage): "She graduated in the transitional class of 1947, when FSCW became the coeducational Florida State University. She was a member of the only class for which both institutional names appear on the diploma." Retrieved on 4-30-2007.

- ^ Davis, Hannah (22 September 2015). "What's in a song? The many melodies of FSU". Illuminations. Heritage Protocol & University Archives. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

- ^ "Florida State University: A History of Traditions – Page 26". The FSU Fight Song. FSU Student Government Association. 9 August 2010. Retrieved October 11, 2011.

- ^ "Florida State University - Fight Song (lyrics by Doug Alley, music by Thomas Wright)'". Archived from the original on 2007-06-14. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- ^ "The History of the War Chant". Archived from the original on 2007-04-01. Retrieved 2007-05-28.

- ^ "FSU 150th Anniversary - History || Co-Education Returns || Fight Song". Archived from the original on 2008-04-18. Retrieved 2008-04-23.

- ^ [14] Florida State University, News Archive, Events Retrieved on 4-30-2007.

- ^ "Compression". Archived from the original on 2007-02-27. Retrieved 2007-06-29. Florida State Times - On-Line, April/May 1997 - Compression (©1997 Florida State Times): "Streaking an FSU First - One of the more notorious fads of the 1970s began on the campus of Florida State. Streaking, which swept the nation in the 1970s, was started in 1974 when about 200 FSU students decided to run naked across the campus one mild March evening." Retrieved on 6-29-2007.

- ^ [15] Tallahassee Naturally, Inc. (©2005 by Tallahassee Naturally, Inc. All rights reserved): "January 15, 1974 was a slow day at the Florida Flambeau. So the editor persuaded four male FSU students to streak naked across Woodward Avenue and the tennis courts, on into a waiting getaway car. Within weeks, the streaking fad had spread across campuses nationwide. To uphold their record as Number 1, FSU students staged mass nude evening rallies in front of the library. But the fad quickly passed, and everyone forgot that it had started in Tallahassee." Retrieved on 6-29-2007.

- ^ [16] Florida State University, Center for Participant Education Retrieved on 4-30-2007.

- ^ "White Student To Seek Fla. A. & M. U. Enrollment". Jet. Vol. 17, no. 18. February 20, 1960. p. 51.

- ^ "FSU Black Alumni Association pays tribute to first black student - FSU.com January 30, 2004". Archived from the original on 2007-08-08. Retrieved 2008-04-20.

- ^ a b "Walk With Me - Sports Illustrated November 16, 2005". Retrieved 2008-04-20.[dead link]

- ^ Dean Heller, FSU gets high marks for black graduation rate, FSU Communications (March 2, 2017).

- ^ "Pathways of Excellence". Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-07-06. Florida State University - Pathways of Excellence Retrieved on 5-27-2007.

- ^ "Pathways of Excellence". Archived from the original on 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2007-07-06. Florida State University - Pathways of Excellence Round 2 Academic Cluster Proposals Retrieved on 5-27-2007.

- ^ "Pathways of Excellence". Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-07-06. Florida State University - Pathways of Excellence, New Facilities Retrieved on 5-27-2007.

- ^ Gunman at Florida State Spoke of Being Watched By ASHLEY SOUTHALL and TIMOTHY WILLIAMS NOV. 20, 2014

- ^ "FSU gunman mailed 10 packages before shooting, contents not dangerous"

- ^ NBC News NOV 22 2014 FSU Shooter Myron May Left Message: 'I Do Not Want to Die in Vain' by TRACY CONNOR

Bibliography

[edit]- Adams, Alfred Hugh (1962). A History of Public Higher Education in Florida, 1821‑1961. Florida State University.

- Bush, George G. (1898). History of Education in Florida. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Bureau of Education, Circular of Information 1888, # 7.

- Campbell, Doak Sheridan (1964). A University in Transition: Florida State College for Women and Florida State University, 1941‑1957. Florida State University.

- Dodd, William George (1948). "Early Education in Tallahassee and the West Florida Seminary, Now Florida State University". Florida Historical Quarterly (XXVII): 1‑27.

- Dodd, William George (1952). History of West Florida Seminary. Florida State University. B0007E7WRS.

- Dodd, William George (1952). West Florida Seminary, 1857‑1901; Florida State College, 1901‑1905. Tallahassee.

- Dodd, William George (1958–1959). Florida State College for Women, Notes on the Formative Years (1905‑1920)‑‑With a "Postscript: The Twenties"; and "Epilogue: The Forties 1940‑1944". Tallahassee.

- Marshall, J.Stanley (2006). The Tumultuous Sixties - Campus Unrest and Student Life at a Southern University. Tallahassee: Sentry Press. ISBN 1-889574-25-2.

- McGrotha, Bill (1987). Seminoles! The First Forty Years. Tallahassee Democrat. ISBN 0-9613040-1-4.

- Rhodes, Barbara (1994). At First - The Presbyterian Church in Tallahassee, Florida, 1828-1938. First Presbyterian Church, Tallahassee, Florida.

- Sellers, Robin Jeanne (1995). Femina perfecta: The genesis of Florida State University. FSU Foundation. ISBN 0-9648374-1-2.

External links

[edit]- Florida State University - Main Website

- Florida State University - Official History

- Exploring FSU's Past: A Public History Project, Fall 2006 Archived 2008-01-24 at the Wayback Machine

- Florida State University Heritage & University Archives

- FSU Institute on World War II and the Human Experience

- State Archives of Florida