Bodrum Mosque

| Bodrum Mosque Bodrum Camii | |

|---|---|

The mosque viewed from northwest as of 2014[update] | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°0′31″N 28°57′20″E / 41.00861°N 28.95556°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | church with cross-in-square plan |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Completed | 10th century |

| Specifications | |

| Minaret(s) | 1 |

| Materials | Brick |

Bodrum Mosque (Turkish: Bodrum Camii, or Mesih Paşa Camii named after its converter) in Istanbul, Turkey, is a former Eastern Orthodox church converted into a mosque by the Ottomans.[1] The church was known under the Greek name of Myrelaion (Greek: Eκκλησία του Μυρελαίου).[2]

Location

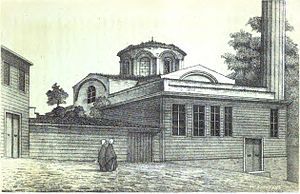

[edit]The beautiful Byzantine structure is today rather incongruously choked on three sides by modern apartment blocks. It stands in Istanbul, in the district of Fatih, in the neighbourhood of Laleli, one kilometre west of the ruins of the Great Palace of Constantinople.

History

[edit]

Some years before 922, possibly during the wars against Simeon I's Bulgaria, the droungarios Romanos Lekapenos bought a house in the ninth region of Constantinople, not far from the Sea of Marmara, in the place called Myrelaion ("the place of myrrh" in Greek).[3] After his accession to the throne this building became the nucleus of a new imperial palace, intended to challenge the neighbouring Great Palace of Constantinople, and the family shrine of the Lekapenos family.[4]

The palace of Myrelaion was built on top of a giant fifth century rotunda which, with an external diameter of 41.8 metres (137.1 feet), was the second largest, after the Roman Pantheon, in the ancient world.[5] In the tenth century the rotunda was not used anymore, and then it was converted – possibly by Romanos himself – into a cistern by covering its interior with a vaulted system carried by at least 70 columns.[6] Near the palace the Emperor built a church, which he intended from the beginning to use as burial place for his family.[7]

The first person to be buried there was his wife Theodora, in December 922, followed by his eldest son and co-emperor Christopher, who died in 931.[8] By doing so, Romanos interrupted a six-century-old tradition, whereby almost all the Byzantine emperors since Constantine I were buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles.

Later the Emperor converted his palace into a nunnery and, after his deposition and death in exile as monk in the island of Prote in June 948, he too was buried in the church.[9]

The shrine was ravaged by fire in 1203,[10] during the Fourth Crusade.[11] Abandoned during the Latin occupation of Constantinople (1204–1261), the building was repaired at the end of the thirteenth century, during the period of the Palaiologan restoration.

After the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, the Myrelaion was converted into a mosque by Grand Vizier Mesih Paşa around the year 1500, during the reign of Bayezid II. The mosque was named after its substructure (the meaning of the Turkish word bodrum is "subterranean vault", "basement"), but was also known under the name of its founder. The edifice was damaged again by fires in 1784 and 1911, when it was abandoned.

In 1930, an excavation led by David Talbot Rice discovered the round cistern. In 1964–1965, a radical restoration led by the Archaeological Museum of Istanbul replaced almost all the external masonry of the edifice, and was then interrupted.[12] In 1965, two parallel excavations led by art historian Cecil L. Striker and by R. Naumann focused respectively on the substructure and on the imperial palace. The building was finally restored in 1986 when it was reopened as mosque. In 1990, the cistern was restored too, and it has hosted a shopping mall for a few years. Now the cistern is used by the women to pray.

Architecture

[edit]

Building

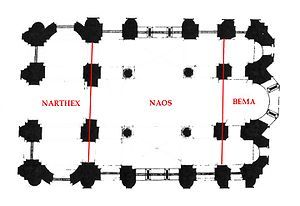

[edit]The building, whose masonry consists entirely of bricks, is built on a foundation structure made of alternated courses of bricks and stone, and has a cross-in-square (or quincunx) plan, with a nine meter long side.[13]

The central nave (naos) is surmounted by an umbrella dome, with a drum interrupted by arched windows, which gives to the structure an undulating rhythmus. The four side naves are covered by barrel vaults. The edifice has a narthex to the west and a sanctuary to the east. The central bay of the narthex is covered by a dome, the two side bays by cross vaults. The nave is partitioned by four piers, which substituted in the Ottoman period the original columns.[14] Many openings – windows, oeil-de-boeufs and arches – give light to the structure.

The exterior of the building is characterized by the half cylindrical buttresses which articulate its façades.[15] Originally an exonarthex existed too, but in the Ottoman period it was replaced by a wooden portico.[13] The building has three polygonal apses. The central one belongs to the sanctuary (bema), while the lateral are parts of two clover-shaped side chapels (pastophoria), prothesis and diakonikon.

The Ottomans built a stone minaret close to the narthex. The building was originally decorated with a marble revetment and mosaics, which disappeared totally. As a whole, Bodrum mosque shows strong analogies with the north church of the Fenari Isa complex.[16]

Substructure

[edit]The substructure, in contrast with the building, has an austere and rough aspect. Originally its purpose was only that of bringing the church to the same level of the palace of Lekapenos. After the restoration in the Palaiologan period it was used as burial chapel.[17]

This edifice is the first example of a private burial church of a Byzantine emperor, starting so a tradition typical of the later Komnenian and Palaiologan periods.[18] Moreover, the building represents a beautiful example of the cross-in-square type church, the new architectural type of the middle Byzantine architecture.[19]

-

Bodrum Mosque interior

-

Bodrum Mosque ceiling

-

Bodrum Mosque interior

-

Bodrum Mosque view from below

-

Bodrum Mosque crypt

-

Bodrum Mosque fresco in crypt

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ It must not be mistaken for the Mesih Mehmed Paşa Camii, which is another mosque founded in the late sixteenth century.

- ^ The identification of the church could be done thanks to the precise description given by Petrus Gillius in his topographic work about Constantinople. Striker (1981), p. 3.

- ^ The seller was one Kraterios. Striker (1981), p. 6.

- ^ The Cambridge Medieval History (1995), p. 563.

- ^ The denomination of this edifice is still unknown. Striker (1981), p. 13.

- ^ Striker (1981), p. 13.

- ^ The emperor brought three marble sarcophagi belonging to the Emperor Maurice and his sons from the church of St. Mamas. Striker (1981), p. 6.

- ^ Striker (1981), p. 6.

- ^ In addition, his daughter Helena, widow of Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos and the only legitimate link of Romanos to the Empire, was buried in the Myrelaion, instead of the Holy Apostles, beside her husband. Striker (1981), p. 6.

- ^ Most probably this happened on 18 August 1203, when a group of Flemish soldiers, aided by Pisan and Venetian sailors, started a major fire in the southern part of Constantinople to cover their retreat. Striker (1981), p. 29.

- ^ During the archaeological excavation near the mosque a fragment of foot of the group of the Tetrarchs was found, thus confirming the tradition that this group (now fixed in the wall of St Mark's Basilica in Venice) had been stolen from the city (possibly from the Philadelphion square) by the Venetians in 1204. Striker (1981), p. 29.

- ^ The "restoration" replaced 90% of the original masonry with new concrete bricks, which revised windows and door lines, erased masonry joints, and eliminated the delicate saw-toothed courses which had originally defined the original lines of the building. Mathews (1976), p. 209.

- ^ a b Krautheimer (1986), p. 403.

- ^ The same happened in many other byzantine churches.

- ^ Striker (1981), p. 17.

- ^ Krautheimer (1986), p. 404.

- ^ During the excavation in the substructure have been found the remains of a fresco representing a female donor making an offering to the Theotokos Hodegetria. Striker (1981), p. 31.

- ^ Other examples are the complex of the Pantokrator and the church of Saint John the Baptist at Lips.

- ^ Striker (1981), p. 35.

Sources

[edit]- Mathews, Thomas F. (1976). The Byzantine Churches of Istanbul: A Photographic Survey. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 0-271-01210-2.

- Gülersoy, Çelik (1976). A guide to Istanbul. Istanbul: Istanbul Kitaplığı. OCLC 3849706.

- Striker, Cecil L. (1981). The Myrelaion (Bodrum Camii) in Istanbul. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Krautheimer, Richard (1986). Architettura paleocristiana e bizantina (in Italian). Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 88-06-59261-0.