Music of Italy

| Music of Italy | ||||||||

| General topics | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genres | ||||||||

| Specific forms | ||||||||

| Gregorian chant | ||||||||

| Media and performance | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Nationalistic and patriotic songs | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Regional music | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Italy |

|---|

|

| People |

| Traditions |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Italian language |

|---|

| History |

| Literature and other |

| Grammar |

| Alphabet |

| Phonology |

In Italy, music has traditionally been one of the cultural markers of Italian national cultures and ethnic identity and holds an important position in society and in politics. Italian music innovation – in musical scale, harmony, notation, and theatre – enabled the development of opera and much of modern European classical music – such as the symphony and concerto – ranges across a broad spectrum of opera and instrumental classical music and popular music drawn from both native and imported sources. Instruments associated with classical music, including the piano and violin, were invented in Italy.[1]

Italy's most famous composers include the Renaissance Palestrina, Monteverdi, and Gesualdo; the Baroque Scarlatti, and Vivaldi; the classical Paganini, and Rossini; and the Romantic Verdi and Puccini. Classical music has a strong hold in Italy, as evidenced by the fame of its opera houses such as La Scala, and performers such as the pianist Maurizio Pollini and tenor Luciano Pavarotti. Italy is known as the birthplace of opera.[2] Italian opera is believed to have been founded in the 17th century.[2]

Italian folk music is an important part of the country's musical heritage, and spans a diverse array of regional styles, instruments and dances. Instrumental and vocal classical music is an iconic part of Italian identity, spanning experimental art music and international fusions to symphonic music and opera. Opera is integral to Italian musical culture, and has become a major segment of popular music. The Canzone Napoletana—the Neapolitan Song, and the cantautori singer-songwriter traditions are also popular domestic styles that form an important part of the Italian music industry.

Introduced in the early 1920s, jazz gained a strong foothold in Italy, and remained popular despite xenophobic policies of the Fascists. Italy was represented in the progressive rock and pop movements of the 1970s, with bands such as PFM, Banco del Mutuo Soccorso, Le Orme, Goblin, and Pooh.[3] The same period saw diversification in the cinema of Italy, and Cinecittà films included complex scores by composers including Ennio Morricone. In the 1980s, the first star to emerge from Italian hip hop was singer Jovanotti.[4] Italian metal bands include Rhapsody of Fire, Lacuna Coil, Elvenking, Forgotten Tomb, and Fleshgod Apocalypse.[5]

Italy contributed to the development of disco and electronic music, with Italo disco, known for its futuristic sound and prominent use of synthesisers and drum machines, one of the earliest electronic dance genres.[6] Producers such as Giorgio Moroder, who won three Academy Awards and four Golden Globes, were influential in the development of electronic dance music.[7] Italian pop is represented annually with the Sanremo Music Festival, which served as inspiration for the Eurovision Song Contest.[8] Gigliola Cinquetti, Toto Cutugno, and Måneskin won Eurovision, in 1964, 1990, and 2021 respectively. Singers such as Domenico Modugno, Mina, Andrea Bocelli, Raffaella Carrà, Il Volo, Al Bano, Toto Cutugno, Nek, Umberto Tozzi, Giorgia, Grammy winner Laura Pausini, Eros Ramazzotti, Tiziano Ferro, Måneskin, Mahmood, Ghali have received international acclaim.[9]

Characteristics

[edit]Italian music has been held up in high esteem in history and many pieces of Italian music are considered high art. More than other elements of Italian culture, music is generally eclectic, but unique from other nations' music. The country's historical contributions to music are also an important part of national pride. The relatively recent history of Italy includes the development of an opera tradition that has spread throughout the world; prior to the development of Italian identity or a unified Italian state, the Italian peninsula contributed to important innovations in music including the development of musical notation and Gregorian chant.

Social identity

[edit]Italy has a strong sense of national identity through distinctive culture – a sense of an appreciation of beauty and emotionality, which is strongly evidenced in the music. Cultural, political and social issues are often also expressed through music in Italy. Allegiance to music is integrally woven into the social identity of Italians but no single style has been considered a characteristic "national style". Most folk music is localized, and unique to a small region or city.[10][11] Italy's classical legacy, however, is an important point of the country's identity, particularly opera; traditional operatic pieces remain a popular part of music and an integral component of national identity. The musical output of Italy remains characterized by "great diversity and creative independence (with) a rich variety of types of expression".[11]

With the growing industrialization that accelerated during the 20th and 21st century, Italian society gradually moved from an agricultural base to an urban and industrial center. This change weakened traditional culture in many parts of society; a similar process occurred in other European countries, but unlike them, Italy had no major initiative to preserve traditional musics. Immigration from North Africa, Asia, and other European countries led to further diversification of Italian music. Traditional music came to exist only in small pockets, especially as part of dedicated campaigns to retain local musical identities.[12]

Politics

[edit]

Music and politics have been intertwined for centuries in Italy. Just as many works of art in the Italian Renaissance were commissioned by royalty and the Catholic Church, much music was likewise composed on the basis of such commissions—incidental court music, music for coronations, for the birth of a royal heir, royal marches, and other occasions. Composers who strayed ran certain risks. Among the best known of such cases was the Neapolitan composer Domenico Cimarosa, who composed the Republican hymn for the short-lived Neapolitan Republic of 1799. When the republic fell, he was tried for treason along with other revolutionaries. Cimarosa was not executed by the restored monarchy, but he was exiled.[15]

Music also played a role in the unification of the peninsula. During this period, some leaders attempted to use music to forge a unifying cultural identity. One example is the chorus "Va, pensiero" from Giuseppe Verdi's opera Nabucco. The opera is about ancient Babylon kingdom, but the chorus contains the phrase "O mia Patria", ostensibly about the struggle of the Israelites confederation, but also a thinly veiled reference to the destiny of a not-yet-united Italy; the entire chorus became the unofficial anthem of the Risorgimento, the drive to unify Italy in the 19th century. Even Verdi's name was a synonym for Italian unity because "Verdi" could be read as an acronym for Vittorio Emanuele Re d'Italia, Victor Emanuel King of Italy, the Savoy monarch who eventually became Victor Emanuel II, the first king of united Italy. Thus, "Viva Verdi" was a rallying cry for patriots and often appeared in graffiti in Milan and other cities in what was then part of Austro-Hungarian territory. Verdi had problems with censorship before the unification of Italy. His opera Un ballo in maschera was originally entitled Gustavo III and was presented to the San Carlo opera in Naples, the capital of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, in the late 1850s. The Neapolitan censors objected to the realistic plot about the assassination of Gustav III, King of Sweden, in the 1790s. Even after the plot was changed, the Neapolitan censors still rejected it.[16]

Later, in the Fascist era of the 1920s and 30s, government censorship and interference with music occurred, though not on a systematic basis. Prominent examples include the notorious anti-modernist manifesto of 1932[17] and Mussolini's banning of G.F. Malipiero's opera La favola del figlio cambiato after one performance in 1934.[18] The music media often criticized music that was perceived as either politically radical or insufficiently Italian.[11] General print media, such as the Enciclopedia Moderna Italiana, tended to treat traditionally favored composers such as Giacomo Puccini and Pietro Mascagni with the same brevity as composers and musicians that were not as favored—modernists such as Alfredo Casella and Ferruccio Busoni; that is, encyclopedia entries of the era were mere lists of career milestones such as compositions and teaching positions held. Even the conductor Arturo Toscanini, an avowed opponent of Fascism,[19] gets the same neutral and distant treatment with no mention at all of his "anti-regime" stance.[20] Perhaps the best-known episode of music colliding with politics involves Toscanini. He had been forced out of the musical directorship at La Scala in Milan in 1929 because he refused to begin every performance with the fascist song, "Giovinezza". For this insult to the regime, he was attacked and beaten on the street outside the Bologne opera after a performance in 1931.[21] During the Fascist era, political pressure stymied the development of classical music, although censorship was not as systematic as in Nazi Germany. A series of "racial laws" was passed in 1938, thus denying to Jewish composers and musicians membership in professional and artistic associations.[a] Although there was not a massive flight of Italian Jews from Italy during this period (compared to the situation in Germany)[b] composer Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, an Italian Jew, was one of those who emigrated. Some non-Jewish foes of the regime also emigrated—Toscanini, for one.[22][23]

More recently, in the later part of the 20th century, especially in the 1970s and beyond, music became further enmeshed in Italian politics.[23] A roots revival stimulated interest in folk traditions, led by writers, collectors and traditional performers.[11] The political right in Italy viewed this roots revival with disdain, as a product of the "unprivileged classes".[24] The revivalist scene thus became associated with the opposition, and became a vehicle for "protest against free-market capitalism".[11] Similarly, the avant-garde classical music scene has, since the 1970s, been associated with and promoted by the Italian Communist Party, a change that can be traced back to the 1968 student revolts and protests.[12]

Classical music

[edit]Italy has long been a center for European classical music, and by the beginning of the 20th century, Italian classical music had forged a distinct national sound that was decidedly Romantic and melodic. As typified by the operas of Verdi, it was music in which "... The vocal lines always dominate the tonal complex and are never overshadowed by the instrumental accompaniments ..."[25] Italian classical music had resisted the "German harmonic juggernaut"[26]—that is, the dense harmonies of Richard Wagner, Gustav Mahler and Richard Strauss. Italian music also had little in common with the French reaction to that German music—the impressionism of Claude Debussy, for example, in which melodic development is largely abandoned for the creation of mood and atmosphere through the sounds of individual chords.[27]

European classical music changed greatly in the 20th century. New music abandoned much of the historical, nationally developed schools of harmony and melody in favor of experimental music, atonality, minimalism and electronic music, all of which employ features that have become common to European music in general and not Italy specifically.[28] These changes have also made classical music less accessible to many people. Important composers of the period include Ottorino Respighi, Ferruccio Busoni, Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Franco Alfano, Bruno Maderna, Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, Sylvano Bussotti, Salvatore Sciarrino, Luigi Dallapiccola, Carlo Jachino, Gian Carlo Menotti, Jacopo Napoli, and Goffredo Petrassi.

Opera

[edit]

Opera originated in Italy in the late 16th century during the time of the Florentine Camerata. Through the centuries that followed, opera traditions developed in Naples and Venice; the operas of Claudio Monteverdi, Alessandro Scarlatti, Giambattista Pergolesi, and, later, of Gioacchino Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Gaetano Donizetti flourished. Opera has remained the musical form most closely linked with Italian music and Italian identity. This was most obvious in the 19th century through the works of Giuseppe Verdi, an icon of Italian culture and pan-Italian unity. Italy retained a Romantic operatic musical tradition in the early 20th century, exemplified by composers of the so-called Giovane Scuola, whose music was anchored in the previous century, including Arrigo Boito, Ruggiero Leoncavallo, Pietro Mascagni, and Francesco Cilea. Giacomo Puccini, who was a realist composer, has been described by Encyclopædia Britannica Online as the man who "virtually brought the history of Italian opera to an end".[29]

After World War I, however, opera declined in comparison to the popular heights of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Causes included the general cultural shift away from Romanticism and the rise of the cinema, which became a major source of entertainment. A third cause is the fact that "internationalism" had brought contemporary Italian opera to a state where it was no longer "Italian".[12] This was the opinion of at least one prominent Italian musicologist and critic, Fausto Terrefranca, who, in a 1912 pamphlet entitled Giaccomo Puccini and International Opera, accused Puccini of "commercialism" and of having deserted Italian traditions. Traditional Romantic opera remained popular; indeed, the dominant opera publisher in the early 20th century was Casa Ricordi, which focused almost exclusively on popular operas until the 1930s, when the company allowed more unusual composers with less mainstream appeal. The rise of relatively new publishers such as Carisch and Suvini Zerboni also helped to fuel the diversification of Italian opera.[12] Opera remains a major part of Italian culture; renewed interest in opera across the sectors of Italian society began in the 1980s. Respected composers from this era include the well-known Aldo Clementi, and younger peers such as Marco Tutino and Lorenzo Ferrero.[12]

Sacred music

[edit]Italy, being one of Catholicism's seminal nations, has a long history of music for the Catholic Church. Until approximately 1800, it was possible to hear Gregorian Chant and Renaissance polyphony, such as the music of Palestrina, Lassus, Anerio, and others. Approximately 1800 to approximately 1900 was a century during which a more popular, operatic, and entertaining type of church music was heard, to the exclusion of the aforementioned chant and polyphony. In the late 19th century, the Cecilian Movement was started by musicians who fought to restore this music. This movement gained impetus not in Italy but in Germany, particularly in Regensburg. The movement reached its apex around 1900 with the ascent of Don Lorenzo Perosi and his supporter (and future saint), Pope Pius X.[30] The advent of Vatican II, however, nearly obliterated all Latin-language music from the Church, once again substituting it with a more popular style.[31]

Instrumental music

[edit]Baroque and Classical

[edit]

The dominance of opera in Italian music tends to overshadow the important area of instrumental music.[32] Historically, such music includes the vast array of sacred instrumental music, instrumental concertos, and orchestral music in the works of Andrea Gabrieli, Giovanni Gabrieli, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Giuseppe Garibaldi, Tomaso Albinoni, Arcangelo Corelli, Antonio Vivaldi, Domenico Scarlatti, Luigi Boccherini, Muzio Clementi, Giuseppe Gariboldi, Luigi Cherubini, Giovanni Battista Viotti and Niccolò Paganini. (Even opera composers occasionally worked in other forms—Giuseppe Verdi's String Quartet in E minor, for example. Even Donizetti, whose name is identified with the beginnings of Italian lyric opera, wrote 18 string quartets.) In the early 20th century, instrumental music began growing in importance, a process that started around 1904 with Giuseppe Martucci's Second Symphony, a work that Gian Francesco Malipiero called "the starting point of the renaissance of non-operatic Italian music."[33] Several early composers from this era, such as Leone Sinigaglia, used native folk traditions.

Romantic to Modern

[edit]The early 20th century is also marked by the presence of a group of composers called the generazione dell'ottanta (generation of 1880), including Franco Alfano, Alfredo Casella, Gian Francesco Malipiero, Ildebrando Pizzetti, and Ottorino Respighi. These composers usually concentrated on writing instrumental works, rather than opera. Members of this generation were the dominant figures in Italian music after Puccini's death in 1924.[12] New organizations arose to promote Italian music, such as the Venice Festival of Contemporary Music and the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino. Guido M. Gatti's founding of the periodical Il Pianoforte and then La rassegna musicale also helped to promote a broader view of music than the political and social climate allowed. Most Italians, however, preferred more traditional pieces and established standards, and only a small audience sought new styles of experimental classical music.[12]

Italy is also the homeland of important interpreters, such as Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Quartetto Italiano, I Musici, Salvatore Accardo, Maurizio Pollini, Uto Ughi, Aldo Ciccolini, Severino Gazzelloni, Arturo Toscanini, Mario Brunello, Ferruccio Busoni, Claudio Abbado, Ruggero Chiesa, Bruno Canino, Carlo Maria Giulini, Oscar Ghiglia and Riccardo Muti.

Ballet

[edit]

Italian contributions to ballet are less known and appreciated than in other areas of classical music. Italy, particularly Milan, was a center of court ballet as early as the 15th century, which was influenced by the entertainments common in royal celebrations and aristocratic weddings. Early choreographers and composers of ballet include Fabritio Caroso and Cesare Negri. The style of ballet known as the "spectacles all’italiana" imported to France from Italy caught on, and the first ballet performed in France (1581), Ballet Comique de la Reine, was choreographed by an Italian, Baltazarini di Belgioioso,[34] better known by the French version of his name, Balthasar de Beaujoyeulx. Early ballet was accompanied by considerable instrumentation, with the playing of horns, trombones, kettle drums, dulcimers, bagpipes, etc. Although the music has not survived, there is speculation that dancers, themselves, may have played instruments on stage.[35] Then, in the wake of the French Revolution, Italy again became a center of ballet, largely through the efforts of Salvatore Viganò, a choreographer who worked with some of the most prominent composers of the day. He became balletmaster at La Scala in 1812.[34] The best-known example of Italian ballet from the 19th century is probably Excelsior, with music by Romualdo Marenco and choreography by Luigi Manzotti. It was composed in 1881 and is a lavish tribute to the scientific and industrial progress of the 19th century. It is still performed and was staged as recently as 2002.

Currently, major Italian opera theaters maintain ballet companies. They exist to provide incidental and ceremonial dancing in many operas, such as Aida or La Traviata. These dance companies usually maintain a separate ballet season and perform the standard repertoire of classical ballet, little of which is Italian. The Italian equivalent of the Russian Bolshoi Ballet and similar companies that exist only to perform ballet, independent of a parent opera theater is La Scala Theatre Ballet. In 1979, a modern dance company, Aterballetto, was founded in Reggio Emilia by Vittorio Biagi.

Experimental music

[edit]

Experimental music is a broad, loosely defined field encompassing musics created by abandoning traditional classical concepts of melody and harmony, and by using the new technology of electronics to create hitherto impossible sounds. In Italy, one of the first to devote his attention to experimental music was Ferruccio Busoni, whose 1907 publication, Sketch for a New Aesthetic of Music, discussed the use of electrical and other new sounds in future music. He spoke of his dissatisfaction with the constraints of traditional music:

- "We have divided the octave into twelve equidistant degrees…and have constructed our instruments in such as way that we can never get in above or below or between them…our ears are no longer capable of hearing anything else…yet Nature created an infinite gradation—infinite! Who still knows it nowadays?"[36]

Similarly, Luigi Russolo, the Italian Futurist painter and composer, wrote of the possibilities of new music in his 1913 manifestoes The Art of Noises and Musica Futurista. He also invented and built instruments such as the intonarumori, mostly percussion, which were used in a precursor to the style known as musique concrète. One of the most influential events in early 20th century music was the return of Alfredo Casella from France in 1915; Casella founded the Società Italiana di Musica Moderna, which promoted several composers in disparate styles, ranging from experimental to traditional. After a dispute over the value of experimental music in 1923, Casella formed the Corporazione delle Nuove Musiche to promote modern experimental music.[12]

In the 1950s, Luciano Berio experimented with instruments accompanied by electronic sounds on tape. In modern Italy, one important organization that fosters research in avantgarde and electronic music is CEMAT, the Federation of Italian Electroacoustic Music Centers. It was founded in 1996 in Rome and is a member of the CIME, the Confédération Internationale de Musique Electroacoustique. CEMAT promotes the activities of the "Sonora" project, launched jointly by the Department for Performing Arts, Ministry for Cultural Affairs and the Directorate for Cultural Relations, Ministry for Foreign Affairs with the object of promoting and diffusing Italian contemporary music abroad.

Classical music in society

[edit]Italian classical music grew gradually more experimental and progressive into the mid-20th century, while popular tastes have tended to stick with well established composers and compositions of the past.[12] The 2004–2005 program at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples is typical of modern Italy: of the eight operas represented, the most recent was Puccini. In symphonic music, of the 26 composers whose music was played, 21 of them were from the 19th century or earlier, composers who use the melodies and harmonies typical of the Romantic era. This focus is common to other European traditions, and is known as postmodernism, a school of thought that draws on earlier harmonic and melodic concepts that pre-date the conceptions of atonality and dissonance.[37] This focus on popular historical composers has helped to maintain a continued presence of classical music across a broad spectrum of Italian society. When music is part of a public display or gathering, it is often chosen from a very eclectic repertoire that is as likely to include well-known classical music as popular music.

A few recent works have become a part of the modern repertoire, including scores and theatrical works by composers such as Luciano Berio, Luigi Nono, Franco Donatoni, and Sylvano Bussotti. These composers are not part of a distinct school or tradition, though they do share certain techniques and influences. By the 1970s, avant-garde classical music had become linked to the Italian Communist Party, while a revival of popular interest continued into the next decade, with foundations, festivals and organization created to promote modern music. Near the end of the 20th century, government sponsorship of musical institutions began to decline, and several RAI choirs and city orchestras were closed. Despite this, a number of composers gained international reputations in the early 21st century.[12]

Folk music

[edit]Italian folk music has a deep and complex history.[38] Because national unification came late to the Italian peninsula, the traditional music of its many hundreds of cultures exhibit no homogeneous national character. Rather, each region and community possesses a unique musical tradition that reflects the history, language, and ethnic composition of that particular locale.[39] These traditions reflect Italy's geographic position in southern Europe and in the centre of the Mediterranean; Celtic, Slavic, Greek, and Byzantine influences, as well as rough geography and the historic dominance of small city states, have all combined to allow diverse musical styles to coexist in close proximity.

Italian folk styles are very diverse, and include monophonic, polyphonic, and responsorial song, choral, instrumental and vocal music, and other styles. Choral singing and polyphonic song forms are primarily found in northern Italy, while south of Naples, solo singing is more common, and groups usually use unison singing in two or three parts carried by a single performer. Northern ballad-singing is syllabic, with a strict tempo and intelligible lyrics, while southern styles use a rubato tempo, and a strained, tense vocal style.[40] Folk musicians use the dialect of their own regional tradition; this rejection of the standard Italian language in folk song is nearly universal. There is little perception of a common Italian folk tradition, and the country's folk music never became a national symbol.[41]

Regions

[edit]

Folk music is sometimes divided into several spheres of geographic influence, a classification system of three regions, southern, central and northern, proposed by Alan Lomax in 1956[42] and often repeated. Additionally, Curt Sachs proposed the existence of two quite distinct kinds of folk music in Europe: continental and Mediterranean.[43] Others have placed the transition zone from the former to the latter roughly in north-central Italy, approximately between Pesaro and La Spezia.[44] The central, northern and southern parts of the peninsula each share certain musical characteristics, and are each distinct from the music of Sardinia.[40]

In the Piedmontese valleys and some Ligurian communities of northwestern Italy, the music preserves the strong influence of ancient Occitania. The lyrics of the Occitanic troubadours are some of the oldest preserved samples of vernacular song, and modern bands like Gai Saber and Lou Dalfin preserve and contemporize Occitan music. The Occitanian culture retains characteristics of the ancient Celtic influence, through the use of six- or seven-hole flutes (fifre) or the bagpipes (piva). Much of northern Italy shares with areas of Europe further to the north an interest in ballad singing (called canto epico lirico in Italian) and choral singing. Even ballads—usually thought of as a vehicle for a solo voice—may be sung in choirs. In the province of Trento "folk choirs" are the most common form of music making.[45]

Noticeable musical differences in the southern type include increased use of interval part singing and a greater variety of folk instruments. The Celtic and Slavic influences on the group and open-voice choral works of the north yield to a stronger Arabic, Greek, and North African-influenced strident monody of the south.[46] In parts of Apulia (Grecìa Salentina, for example) the Griko dialect is commonly used in song. The Apulian city of Taranto is a home of the tarantella, a rhythmic dance widely performed in southern Italy. Apulian music in general, and Salentine music in particular, has been well researched and documented by ethnomusicologists and by Aramirè.

The music of the island of Sardinia is best known for the polyphonic chanting of the tenores. The sound of the tenores recalls the roots of Gregorian chant, and is similar to but distinctive from the Ligurian trallalero. Typical instruments include the launeddas, a Sardinian triplepipe used in a sophisticated and complex manner. Efisio Melis was a well-known master launeddas player of the 1930s.[47]

Songs

[edit]Italian folk songs include ballads, lyrical songs, lullabies and children's songs, seasonal songs based around holidays such as Christmas, life-cycle songs that celebrate weddings, baptisms and other important events, dance songs, cattle calls and occupational songs, tied to professions such as fishermen, shepherds and soldiers. Ballads (canti epico-lirici) and lyric songs (canti lirico-monostrofici) are two important categories. Ballads are most common in northern Italy, while lyric songs prevail further south. Ballads are closely tied to the English form, with some British ballads existing in exact correspondence with an Italian song. Other Italian ballads are more closely based on French models. Lyric songs are a diverse category that consist of lullabies, serenades and work songs, and are frequently improvised though based on a traditional repertoire.[40]

Other Italian folk song traditions are less common than ballads and lyric songs. Strophic, religious laude, sometimes in Latin, are still occasionally performed, and epic songs are also known, especially those of the maggio celebration. Professional female singers perform dirges similar in style to those elsewhere in Europe. Yodeling exists in northern Italy, though it is most commonly associated with the folk musics of other Alpine nations. The Italian Carnival is associated with several song types, especially the Carnival of Bagolino, Brescia. Choirs and brass bands are a part of the mid-Lenten holiday, while the begging song tradition extends through many holidays throughout the year.[40]

Instrumentation

[edit]

Instrumentation is an integral part of all facets of Italian folk music. There are several instruments that retain older forms even while newer models have become widespread elsewhere in Europe. Many Italian instruments are tied to certain rituals or occasions, such as the zampogna bagpipe, typically heard only at Christmas.[48] Italian folk instruments can be divided into string, wind and percussion categories.[49] Common instruments include the organetto, an accordion most closely associated with the saltarello; the diatonic button organetto is most common in central Italy, while chromatic accordions prevail in the north. Many municipalities are home to brass bands, which perform with roots revival groups; these ensembles are based around the clarinet, accordion, violin and small drums, adorned with bells.[40]

Italy's wind instruments include most prominently a variety of folk flutes. These include duct, globular and transverse flutes, as well as various variations of the pan flute. Double flutes are most common in Campania, Calabria and Sicily.[50] A ceramic pitcher called the quartara is also used as a wind instrument, by blowing across an opening in the narrow bottle neck; it is found in eastern Sicily and Campania. Single- (ciaramella) and double-reed (piffero) pipes are commonly played in groups of two or three.[40] Several folk bagpipes are well-known, including central Italy's zampogna; dialect names for the bagpipe vary throughout Italy-- eghet in Bergamo, piva in Lombardy, müsa in Alessandria, Genoa, Pavia and Piacenza, and so forth.

Numerous percussion instruments are a part of Italian folk music, including wood blocks, bells, castanets, drums. Several regions have their own distinct form of rattle, including the raganella cog rattle and the Calabrian conocchie, a spinning or shepherd's staff with permanently attached seed rattles with ritual fertility significance. The Neapolitan rattle is the triccaballacca, made out of several mallets in a wooden frame. Tambourines (tamburini, tamburello), as are various kinds of drums, such as the friction drum putipù. The tamburello, while appearing very similar to the contemporary western tambourine, is actually played with a much more articulate and sophisticated technique (influenced by Middle Eastern playing), giving it a wide range of sounds. The mouth-harp, scacciapensieri or care-chaser, is a distinctive instrument, found only in northern Italy and Sicily.[40]

String instruments vary widely depending on locality, with no nationally prominent representative. Viggiano is home to a harp tradition, which has a historical base in Abruzzi, Lazio and Calabria. Calabria, alone, has 30 traditional musical instruments, some of which have strongly archaic characteristics and are largely extinct elsewhere in Italy. It is home to the four- or five-stringed guitar called the chitarra battente, and a three-stringed, bowed fiddle called the lira,[51] which is also found in similar forms in the music of Crete and Southeastern Europe. A one-stringed, bowed fiddle called the torototela, is common in the northeast of the country. The largely German-speaking area of South Tyrol is known for the zither, and the ghironda (hurdy-gurdy) is found in Emilia, Piedmont and Lombardy.[40] Existing, rooted and widespread traditions confirm the production of ephemeral and toy instruments made of bark, reed (arundo donax), leaves, fibers and stems, as it emerges, for example, from Fabio Lombardi's research.

Dance

[edit]

Dance is an integral part of folk traditions in Italy. Some of the dances are ancient and, to a certain extent, persist today. There are magico-ritual dances of propitiation as well as harvest dances, including the "sea-harvest" dances of fishing communities in Calabria and the wine harvest dances in Tuscany. Famous dances include the southern tarantella; perhaps the most iconic of Italian dances, the tarantella is in 6/8 time, and is part of a folk ritual intended to cure the poison caused by tarantula bites. Popular Tuscan dances ritually act out the hunting of the hare, or display blades in weapon dances that simulate or recall the moves of combat, or use the weapons as stylized instruments of the dance itself. For example, in a few villages in northern Italy, swords are replaced by wooden half-hoops embroidered with green, similar to the so-called "garland dances" in northern Europe.[52] There are also dances of love and courting, such as the duru-duru dance in Sardinia.[53]

Many of these dances are group activities, the group setting up in rows or circles; some—the love and courting dances—involve couples, either a single couple or more. The tammuriata (performed to the sound of the tambourine) is a couple dance performed in southern Italy and accompanied by a lyric song called a strambotto. Other couples dances are collectively referred to as saltarello.[40] There are, however, also solo dances; most typical of these are the "flag dances" of various regions of Italy, in which the dancer passes a town flag or pennant around the neck, through the legs, behind the back, often tossing it high in the air and catching it. These dances can also be done in groups of solo dancers acting in unison or by coordinating flag passing between dancers. Northern Italy is also home to the monferrina, an accompanied dance that was incorporated in Western art music by the composer Muzio Clementi.[40]

Academic interest in the study of dance from the perspectives of sociology and anthropology has traditionally been neglected in Italy but is currently showing renewed life at the university and post-graduate level.[54]

Popular music

[edit]The earliest Italian popular music was the opera of the 19th century. Opera has had a lasting effect on Italy's classical and popular music. Opera tunes spread through brass bands and itinerant ensembles. Canzone Napoletana, or Neapolitan song, is a distinct tradition that became a part of popular music in the 19th century, and was an iconic image of Italian music abroad by the end of the 20th century.[40] Imported styles have also become an important part of Italian popular music, beginning with the French Café-chantant in the 1890s and then the arrival of American jazz in the 1910s. Until Italian Fascism became officially "allergic" to foreign influences in the late 1930s, American dance music and musicians were quite popular; jazz great Louis Armstrong toured Italy as late as 1935 to great acclaim.[55] In the 1950s, American styles became more prominent, especially rock. The singer-songwriter cantautori tradition was a major development of the later 1960s, while the Italian rock scene soon diversified into progressive, punk, funk and folk-based styles.[40]

Early popular song

[edit]Italian opera became immensely popular in the 19th century and was known across even the most rural sections of the country. Most villages had occasional opera productions, and the techniques used in opera influenced rural folk musics. Opera spread through itinerant ensembles and brass bands, focused in a local village. These civic bands (banda communale) used instruments to perform operatic arias, with trombones or fluegelhorns for male vocal parts and cornets for female parts.[40]

Regional music in the 19th century also became popular throughout Italy. Notable among these local traditions was the Canzone Napoletana—the Neapolitan Song. Although there are anonymous, documented songs from Naples from many centuries ago,[56] the term, canzone Napoletana now generally refers to a large body of relatively recent, composed popular music—such songs as "'O Sole Mio", "Torna a Surriento", and "Funiculi Funicula". In the 18th century, many composers, including Alessandro Scarlatti, Leonardo Vinci, and Giovanni Paisiello, contributed to the Neapolitan tradition by using the local language for the texts of some of their comic operas. Later, others—most famously Gaetano Donizetti—composed Neapolitan songs that garnered great renown in Italy and abroad.[40] The Neapolitan song tradition became formalized in the 1830s through an annual songwriting competition for the yearly Piedigrotta festival,[57] dedicated to the Madonna of Piedigrotta, a well-known church in the Mergellina area of Naples. The music is identified with Naples, but is famous abroad, having been exported on the great waves of emigration from Naples and southern Italy roughly between 1880 and 1920. Language is an extremely important element of Neapolitan song, which is always written and performed in Neapolitan,[58] the regional minority language of Campania. Neapolitan songs typically use simple harmonies, and are structured in two sections, a refrain and narrative verses, often in contrasting relative or parallel major and minor keys.[40] In non-musical terms, this means that many Neapolitan songs can sound joyful one minute and melancholy the next.

The music of Francesco Tosti was popular at the turn of the 20th century, and is remembered for his light, expressive songs. His style became very popular during the Belle Époque and is often known as salon music. His most famous works are Serenata, Addio and the popular Neapolitan song, Marechiaro, the lyrics of which are by the prominent Neapolitan dialect poet, Salvatore di Giacomo.

Recorded popular music began in the late 19th century, with international styles influencing Italian music by the late 1910s; however, the rise of autarchia, the Fascist policy of cultural isolationism in 1922 led to a retreat from international popular music. During this period, popular Italian musicians traveled abroad and learned elements of jazz, Latin American music and other styles. These musics influenced the Italian tradition, which spread around the world and further diversified following liberalization after World War II.[40]

Under the isolationist policies of the fascist regime, which rose to power in 1922, Italy developed an insular musical culture. Foreign musics were suppressed while Mussolini's government encouraged nationalism and linguistic and ethnic purity. Popular performers, however, travelled abroad, and brought back new styles and techniques.[40] American jazz was an important influence on singers such as Alberto Rabagliati, who became known for a swinging style. Elements of harmony and melody from both jazz and blues were used in many popular songs, while rhythms often came from Latin dances like the tango, rumba and beguine. Italian composers incorporated elements from these styles, while Italian music, especially Neapolitan song, became a part of popular music across Latin America.[40]

Modern pop

[edit]

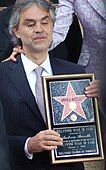

Among the best-known Italian pop musicians of the last few decades are Domenico Modugno, Mina, Mia Martini, Adriano Celentano, Claudio Baglioni, Ornella Vanoni, Patty Pravo and, more recently, Zucchero, Mango, Vasco Rossi, Gianna Nannini and international superstar Laura Pausini and Andrea Bocelli. Musicians who compose and sing their own songs are called cantautori (singer-songwriters). Their compositions typically focus on topics of social relevance and are often protest songs: this wave began in the 1960s with musicians like Fabrizio De André, Paolo Conte, Giorgio Gaber, Umberto Bindi, Gino Paoli and Luigi Tenco.

Social, political, psychological and intellectual themes, mainly in the wake of Gaber and De André's work, became even more predominant in the 1970s through authors such as Lucio Dalla, Pino Daniele, Francesco De Gregori, Ivano Fossati, Francesco Guccini, Edoardo Bennato, Rino Gaetano and Roberto Vecchioni. Lucio Battisti, from the late 1960s until the mid-1990s, merged the Italian music with the British rock and pop and, lately in his career, with genres like the synthpop, rap, techno and Eurodance, while Angelo Branduardi and Franco Battiato pursued careers more oriented to the tradition of Italian pop music.[59] There is some genre cross-over between the cantautori and those who are viewed as singers of "protest music".[60]

Film scores, although they are secondary to the film, are often critically acclaimed and very popular in their own right. Among early music for Italian films from the 1930s was the work of Riccardo Zandonai with scores for the films La Principessa Tarakanova (1937) and Caravaggio (1941). Post-war examples include Goffredo Petrassi with Non c'e pace tra gli ulivi (1950) and Roman Vlad with Giulietta e Romeo (1954). Another well-known film composer was Nino Rota whose post-war career included the scores for films by Federico Fellini and, later, The Godfather series. Other prominent film score composers include Ennio Morricone, Riz Ortolani and Piero Umiliani.[61]

Italian pop music in the 2000s managed to cross national borders thanks, among others, to Laura Pausini, Eros Ramazzotti, Zucchero, Andrea Bocelli, Tiziano Ferro, and Il Volo.[62]

-

Mina, the estimated best-selling Italian singer

-

Mia Martini, critically acclaimed singer

Modern dance

[edit]

Italy has been an important country with regards to electronic dance music, especially ever since the creation of Italo disco in the late 1970s to early 1980s. The genre, originating from disco, blended "melancholy melodies" with pop and electronic music,[63] making usage of synthesizers and drum machines, which often gave it a futuristic sound. According to an article in The Guardian, in cities such as Verona and Milan, producers would work with singers, using mass-made synthesizers and drum machines, and incorporating them into a mix of experimental music with a "classic-pop sensibility"[63] which would be aimed for nightclubs.[63] The songs produced would often be sold later by labels and companies such as the Milan-based Discomagic.[63]

Italo disco influenced several electronic groups, such as the Pet Shop Boys, Erasure and New Order,[63] as well as genres such as Eurodance, Eurobeat and freestyle. By circa 1988, however, the genre had merged into other forms of European dance and electronic music, one of which was Italo house. Italo house blended elements of Italo disco with traditional house music; its sound was generally uplifting, and made strong usage of piano melodies. Bands of this genre include: Black Box, East Side Beat, and 49ers.

By the latter half of the 1990s, a subgenre of Eurodance known as Italo dance emerged. Taking influences from Italo disco and Italo house, Italo dance generally included synthesizer riffs, a melodic sound, and the usage of vocoders. The genre became mainstream after the release of the single "Blue (Da Ba Dee)" by Eiffel 65, which became one of Italy's most popular electronic groups; their album Europop was crowned as the greatest album of the 1990s by Channel 4.[64] Also, a subgenre of Italo dance known as Lento Violento ("slow and violent") was developed by Gigi D'Agostino as a much slower and harder type of music. The BPM is often reduced to the half of typical Italo dance tracks. The bass is often noticeably loud, and dominates the song.[65]

Over the years, there have been several important Italian dance music composers and producers, such as Giorgio Moroder, who won three Academy Awards and four Golden Globes for his music. His work with synthesizers heavily influenced several music genres such as new wave, techno and house music;[66] he is credited by Allmusic as "One of the principal architects of the disco sound",[67] and is also dubbed the "Father of Disco".[68][69]

Imported styles

[edit]During the Belle Époque, the French fashion of performing popular music at the café-chantant spread throughout Europe.[70] The tradition had much in common with cabaret, and there is overlap between café-chantant, café-concert, cabaret, music hall, vaudeville and other similar styles, but at least in its Italian manifestation, the tradition remained largely apolitical, focusing on lighter music, often risqué, but not bawdy. The first café-chantant in Italy was the Salone Margherita, which opened in 1890 on the premises of the new Galleria Umberto in Naples.[71] Elsewhere in Italy, the Gran Salone Eden in Milan and the Music Hall Olympia in Rome opened shortly thereafter. Café-chantant was alternately known as the Italianized caffè-concerto. The main performer, usually a woman, was called a chanteuse in French; the Italian term, sciantosa, is a direct coinage from the French. The songs, themselves, were not French, but were lighthearted or slightly sentimental songs composed in Italian. That music went out of fashion with the advent of World War I.

The influence of US pop forms has been strong since the end of World War II. Lavish Broadway-show numbers, Big Bands, rock and roll, and hip hop continue to be popular. Latin music, especially Brazilian bossa nova, is also popular, and the Puerto Rican genre of reggaeton is rapidly becoming a mainstream form of dance music. It is now not uncommon for modern Italian pop artists such as Laura Pausini, Eros Ramazzotti, Zucchero or Andrea Bocelli to release some new songs in English or Spanish in addition to the original Italian versions. The group Il Volo sings in Italian, English, Spanish and German. Thus, musical revues, which are standard fare on current Italian television, can easily go, in a single evening, from a big-band number with dancers to an Elvis impersonator to a current pop singer doing a rendition of a Puccini aria.

Jazz found its way into Europe during World War I through the presence of American musicians in military bands playing syncopated music.[72] Yet, even before that, Italy received an inkling of new music from across the Atlantic in the form of Creole singers and dancers who performed at the Eden Theater in Milan in 1904; they billed themselves as the "creators of the cakewalk." The first real jazz orchestras in Italy, however, were formed during the 1920s by bandleaders such as Arturo Agazzi and enjoyed immediate success.[55] In spite of the anti-American cultural policies of the Fascist regime during the 1930s, American jazz remained popular.

In the immediate post-war years, jazz took off in Italy. All American post-war jazz styles, from bebop to free jazz and fusion have their equivalents in Italy. The universality of Italian culture ensured that jazz clubs would spring up throughout the peninsula, that all radio and then television studios would have jazz-based house bands, that Italian musicians would then start nurturing a home grown kind of jazz, based on European song forms, classical composition techniques and folk music. Currently, all Italian music conservatories have jazz departments, and there are jazz festivals each year in Italy, the best known of which is the Umbria Jazz Festival, and there are prominent publications such as the journal, Musica Jazz.

Italian pop rock has produced major stars like Zucchero, and has resulted in many top hits. The industry media, especially television, are important vehicles for such music; the television show Sabato Sera is characteristic.[73] Italy was at the forefront of the progressive rock movement of the 1970s, a style that primarily developed in Europe but also gained audiences elsewhere in the world. It is sometimes considered a separate genre, Italian progressive rock. Italian bands such as The Trip, Area, Premiata Forneria Marconi (PFM), Banco del Mutuo Soccorso, New Trolls, Goblin, Osanna, Saint Just and Le Orme incorporated a mix of symphonic rock and Italian folk music and were popular throughout Europe and the United States as well. Other progressive bands such as Perigeo, Balletto di Bronzo, Museo Rosenbach, Rovescio della Medaglia, Biglietto per l'Inferno or Alphataurus remained little known, but their albums are today considered classics by collectors. A few avant-garde rock bands or artists (Area, Picchio dal Pozzo, Opus Avantra, Stormy Six, Saint Just, Giovanni Lindo Ferretti) gained notoriety for their innovative sound. Progressive rock concerts in Italy tended to have a strong political undertone and an energetic atmosphere. Popular Italian metal bands include Rhapsody of Fire, Lacuna Coil, Elvenking, Forgotten Tomb, and Fleshgod Apocalypse.[5]

The Italian hip hop scene began in the early 1990s with Articolo 31 from Milan, whose style was mainly influenced by East Coast rap. Other early hip hop crews were typically politically oriented, like 99 Posse, who later became more influenced by British trip hop. More recent crews include gangster rappers like Sardinia's La Fossa. Other recently imported styles include techno, trance, and electronica performed by artists including Gabry Ponte, Eiffel 65, and Gigi D`Agostino.[74] Hip hop is especially liked in southern Italy, joined with the southern concept of rispetto (respect, honor), a form of verbal jousting; both facts have helped identify southern Italian music with the African American hip hop style.[75] Additionally, there are many bands in Italy that play a style called patchanka, which is characterized by a mixture of traditional music, punk, reggae, rock and political lyrics. Modena City Ramblers are one of the more popular bands known for their mix of Irish, Italian, punk, reggae and many other forms of music.[74]

Italy has also become a home for a number of Mediterranean fusion projects. These include Al Darawish, a multicultural band based in Sicily and led by Palestinian Nabil Ben Salaméh. The Luigi Cinque Tarantula Hypertext Orchestra is another example, as is the TaraGnawa project by Phaleg and Nour Eddine. Mango is one of the best-known artists who fused pop with world and mediterranean sounds, albums such as Adesso, Sirtaki and Come l'acqua are examples of his style. The Neapolitan popular singer, Massimo Ranieri has also released a CD, Oggi o dimane, of traditional canzone Napoletana with North African rhythms and instruments.[74]

Industry

[edit]

The music industry in Italy made €2.3 billion in 2004. That sum refers to the sale of CDs, music electronics, musical instruments, and ticket sales for live performances. By way of comparison, the Italian recording industry ranks eighth in the world; Italians own 0.7 music albums per capita as opposed to the US, in first-place with 2.7.[76]

Nationwide, there are three state-run and three private TV networks. All provide live music at least some of the time. Many large cities in Italy have local TV stations, as well, which may provide live folk or dialect music often of interest only to the immediate area. The largest of these book and CD chain is Feltrinelli.

Venues, festivals and holidays

[edit]

Venues for music in Italy include concerts at the many music conservatories, symphony halls and opera houses. Italy also has many well-known international music festivals each year, including the Festival of Spoleto, the Festival Puccini and the Wagner Festival in Ravello. Some festivals offer venues to younger composers in classical music by producing and staging winning entries in competitions. The winner, for example, of the "Orpheus" International Competition for New Opera and Chamber music—besides winning considerable prize money—gets to see his or her musical work performed at The Spoleto Festival.[77] There are also dozens of privately sponsored master classes in music each year that put on concerts for the public. Italy is also a common destination for well-known orchestras from abroad; at almost any given time during the busiest season, at least one major orchestra from elsewhere in Europe or North America is playing a concert in Italy. Additionally, public music may be heard at dozens of pop and rock concerts throughout the year. Open-air opera may even be heard, for example, at the ancient Roman amphitheater, the Verona Arena.

Military bands, too, are popular in Italy. At a national level, one of the best-known of these is the concert band of the Guardia di Finanza (Italian Customs/Border Police); it performs many times a year.

Many theaters also routinely stage not just Italian translations of American musicals, but true Italian musical comedy, which are called by the English term musical. In Italian, that term describes a kind of musical drama not native to Italy, a form that employs the American idiom of jazz-pop-and rock-based music and rhythms to move a story along in a combination of songs and dialogue.

Music in religious rituals, especially Catholic, manifests itself in a number of ways. Parish bands, for example, are quite common throughout Italy. They may be as small as four or five members to as many as 20 or 30. They commonly perform at religious festivals specific to a particular town, usually in honor of the town's patron saint. The historic orchestral/choral masterpieces performed in church by professionals are well-known; these include such works as the Stabat Mater by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi and Verdi's Requiem. The Second Vatican Council from 1962 to 1965 revolutionized music in the Catholic Church, leading to an increase in the number of amateur choirs that perform regularly for services; the council also encouraged the congregational singing of hymns, and a vast repertoire of new hymns has been composed in the last 40 years.[78]

There is not a great deal of native Italian Christmas music. The most popular Italian Christmas carol is "Tu scendi dalle stelle", the modern Italian words to which were written by Pope Pius IX in 1870. The melody is a major-key version of an older, minor-key Neapolitan carol "Quanno Nascette Ninno" of Alphonsus Liguori. Other than that, Italians largely sing translations of carols that come from the German and English tradition ("Silent Night", for example). There is no native Italian secular Christmas music, which accounts for the popularity of Italian-language versions of "Jingle Bells" and "White Christmas".[79]

The Sanremo Music Festival is an important venue for popular music in Italy. It has been held annually since 1951 and is currently staged at the Teatro Ariston in Sanremo. It runs for one week in February, and gives veteran and new performers a chance to present new songs. Winning the contest has often been a springboard to industry success. The festival is televised nationally for three hours a night, is hosted by the best-known Italian TV personalities, and has been a vehicle for such performers as Domenico Modugno, perhaps the best-known Italian pop singer of the last 50 years.

Television variety shows are the widest venue for popular music. They change often, but Buona Domenica, Domenica In, and I raccomandati are popular. The longest running musical broadcast in Italy is La Corrida, a three-hour weekly program of amateurs and would-be musicians.[80] It started on the radio in 1968 and moved to TV in 1988. The studio audience bring cow-bells and sirens and are encouraged to show good-natured disapproval. The city with the highest number of rock concerts (of national and international artists) is Milan, with a number close to the other European music capitals, as Paris, London and Berlin.

Education

[edit]

Many institutes of higher education teach music in Italy. About 75 music conservatories provide advanced training for future professional musicians. There are also many private music schools and workshops for instrument building and repair. Private teaching is also quite common in Italy. Elementary and high school students can expect to have one or two weekly hours of music teaching, generally in choral singing and basic music theory, though extracurricular opportunities are rare.[81] Though most Italian universities have classes in related subjects such as music history, performance is not a common feature of university education.

Italy has a specialized system of high schools; students attend, as they choose, a high school for humanities, science, foreign languages, or art—and music (in the "liceo musicale", where instruments, musical theory, composing and musical history are taught as the main subject). Italy does have ambitious, recent programs to expose children to more music. Furthermore, with the recent education reform a specific Liceo musicale e coreutico (2nd level secondary school, ages 14–15 to 18–19) is explicitly indicated by the law decrees.[82] Yet this kind of school has not been set up and is not effectively operational. The state-run television network has started a program to use modern satellite technology to broadcast choral music into public schools.[d]

Scholarship

[edit]Scholarship in the field of collecting, preserving and cataloguing all varieties of music is vast. In Italy, as elsewhere, these tasks are spread over a number of agencies and organizations. Most large music conservatories maintain departments that oversee the research connected with their own collections. Such research is coordinated on a national and international scale via the internet. One prominent institution in Italy is IBIMUS, the Istituto di Bibliografia Musicale, in Rome. It works with other agencies on an international scale through RISM, the Répertoire International des Sources Musicales, an inventory and index of source material. Also, the Discoteca di Stato (National Archives of Recordings) in Rome, founded in 1928, holds the largest public collection of recorded music in Italy with some 230,000 examples of classical music, folk music, jazz, and rock, recorded on everything from antique wax cylinders to modern electronic media.

The scholarly study of traditional Italian music began in about 1850, with a group of early philological ethnographers who studied the impact of music on a pan-Italian national identity. A unified Italian identity only just started to develop after the political integration of the peninsula in 1860. The focus at that time was on the lyrical and literary value of music, rather than the instrumentation; this focus remained until the early 1960s. Two folkloric journals helped to encourage the burgeoning field of study, the Rivista Italiana delle Tradizioni Popolari and Lares, founded in 1894 and 1912, respectively. The earliest major musical studies were on the Sardinian launeddas in 1913–1914 by Mario Giulio Fara; on Sicilian music, published in 1907 and 1921 by Alberto Favara; and studies of the music of Emilia Romagna in 1941 by Francesco Balilla Pratella.[40]

The earliest recordings of Italian traditional music came in the 1920s, but they were rare until the establishment of the Centro Nazionale Studi di Musica Popolare at the National Academy of Santa Cecilia in Rome. The Center sponsored numerous song collection trips across the peninsula, especially to southern and central Italy. Giorgio Nataletti was an instrumental figure in the center, and also made numerous recordings himself. The American scholar Alan Lomax and the Italian, Diego Carpitella, made an exhaustive survey of the peninsula in 1954. By the early 1960s, a roots revival encouraged more study, especially of northern musical cultures, which many scholars had previously assumed maintained little folk culture. The most prominent scholars of this era included Roberto Leydi, Ottavio Tiby and Leo Levi. During the 1970s, Leydi and Carpitella were appointed to the first two chairs of ethnomusicology at universities, with Carpitella at the University of Rome and Leydi at the University of Bologna. In the 1980s, Italian scholars began focusing less on making recordings, and more on studying and synthesizing the information already collected. Others studied Italian music in the United States and Australia, and the folk musics of recent immigrants to Italy.[40]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ "Racial laws" started to be issued in Italy in March 1938; specifically, the one denying Jews membership in professional organizations was the Royal Decree of 5 September 1938, XVI, n. 1390, Art. 4.

- ^ Adams 1939 claims that—on the eve of World War II—most Italians who had fled Italy for political reasons—i.e. "...membership in anti-Fascist organizations..."—were in France and puts the number at about 9,000. The author does not distinguish refugees on the basis of race or creed.

- ^ Thus, it is common to speak of the "music of Cilento," even though these names do not necessarily refer to formal administrative regions or provinces of Italy.

- ^ The program is called Verdincanto.[83]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Erlich, Cyril (1990). The Piano: A History. Oxford University Press, US; Revised edition. ISBN 978-0-1981-6171-4.; Allen, Edward Heron (1914). Violin-making, as it was and is: Being a Historical, Theoretical, and Practical Treatise on the Science and Art of Violin-making, for the Use of Violin Makers and Players, Amateur and Professional. Preceded by An Essay on the Violin and Its Position as a Musical Instrument. E. Howe. Accessed 5 September 2015.

- ^ a b Kimbell, David R.B. (1994). Italian Opera. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-5214-6643-1. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ Keller, Catalano and Colicci (25 September 2017). Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Routledge. pp. 604–625. ISBN 978-1-3515-4426-9.

- ^ Sisario, Ben (3 October 2012). "A Roman Rapper Comes to New York, Where He Can Get Real". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ^ a b Sharpe-Young, Garry (2003). A–Z of Power Metal. Rockdetector Series. Cherry Red Books. ISBN 978-1-901447-13-2.

- ^ McDonnell, John (1 September 2008). "Scene and heard: Italo-disco". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ^ "This record was a collaboration between Philip Oakey, the big-voiced lead singer of the techno-pop band the Human League, and Giorgio Moroder, the Italian-born father of disco who spent the '80s writing synth-based pop and film music." Evan Cater. "Philip Oakey & Giorgio Moroder: Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

- ^ Yiorgos Kasapoglou (27 February 2007). "Sanremo Music Festival kicks off tonight". esctoday.com. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- ^ Cirone, Federica (29 August 2023). "Cantanti italiani, quali sono quelli che hanno avuto più successo all'estero" (in Italian). socialboost.it. Retrieved 5 June 2024.

- ^ New Grove Encyclopedia of Music, "Italy", pg. 664.

- ^ a b c d e Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, pp. 613–614.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j New Grove Encyclopedia of Music, "Italy", pp. 637–680.

- ^ "The Theatre and its history". Teatro di San Carlo's official website. 23 December 2013.

- ^ Griffin, Clive (2007). Opera (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Collins. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-06-124182-6.

- ^ Il Mondo della musica, p. 583

- ^ Il Mondo della musica, p. 163

- ^ Sachs 1987, pp. 23–27

- ^ The episode is cited in "Underscoring Fascism", a book review of Sachs (1987) by John C. G. Waterhouse in The Musical Times, Vol. 129, No. 1744. (Jun. 1988), pp. 298–299

- ^ "Maestro v. Fascism". Time. Vol. XXX1, no. 9. 1938. The article recounts Toscanini's refusal to conduct at the Salzburg Festival in protest of the Nazi annexation of Austria.

- ^ Baldi 1935.

- ^ Sachs 2002, p. [page needed], The episode is infamous and appears in virtually all biographical accounts of Toscanini.

- ^ Niccolodi 1984

- ^ a b Sachs 1987, p. 242: "The politicization of the performing arts, so crudely initiated by the fascists, has been brought to a high level of refinement by their successors."

- ^ Garland (Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, p. [page needed])? refers to the "unprivileged classes" as classi subalterne, a term created by Antonio Gramsci, social philosopher and founder of the Italian Communist Party.

- ^ Ulrich and Pisk, p. 531.[full citation needed]

- ^ Crocker, p. 487.[full citation needed]

- ^ Ulrich and Pisk, pp. 581–582.[full citation needed]

- ^ Crocker, p. 517.[full citation needed]

- ^ "Giacomo Puccini – Italian composer". 11 May 2023.

- ^ Dubiaga, Michael Jr. "Musician to Five Popes: Don Lorenzo Perosi". Seattle Catholic. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Ziegler, Jeff (3 December 1999). "Latin, Gregorian Chant, and the Spirit of Vatican II". University Concourse. V (4). Archived from the original on 11 November 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2006.

- ^ Friedland 1970 provides a complete treatment of what she calls "an almost unexplored segment" of music; that is, "…the orchestral and chamber music produced by Italian composers in the 1800s."

- ^ Cited in the New Grove Encyclopedia of Music, "Italy", pg. 659.

- ^ a b Il Mondo della musica, pp. 139–142

- ^ Bouget 1986

- ^ Busoni 1962, p. 89

- ^ Kramer 1999

- ^ Giurati 1995.

- ^ Sassu 1978.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, pp. 604–625.

- ^ Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, pp. 604–625 note that "during the second half of the nineteenth and part of the twentieth century, opera and so-called Neapolitan popular song served such purposes."

- ^ Lomax 1956, pp. 48–50

- ^ Sachs[full citation needed]

- ^ Magrini (1990), p. 20.[full citation needed]

- ^ Sorce Keller 1984.

- ^ "Musica popolare italiana: tradizione e storia" (in Italian). 7 January 2010. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- ^ Leydi 1990, p. 179.

- ^ Guizzi, pp. 43–44.[full citation needed]

- ^ Olson 1967, pp. 108–109

- ^ Carpitella 1975, pp. 422–428, cited in the Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, p. 616.

- ^ Ricci & Tucci 1988.

- ^ Wolfram 1962

- ^ Il Mondo della musica, pp. 682–687

- ^ Sparti & Veroli 1995.

- ^ a b Mazzoletti 1983

- ^ Vajro 1962, p. 17.

- ^ Murolo 1963, notes to vol. 1.

- ^ Maiden (2)[full citation needed]

- ^ Dizionario.[full citation needed]

- ^ Bordoni & Testani 2006, p. 237

- ^ Fazzini 2006, pp. 7–19.

- ^ Fazzini, pp.7-19

- ^ a b c d e McDonnell, John (1 September 2008). "Scene and heard: Italo-disco". The Guardian.

- ^ Eiffel 65 planet – Discography

- ^ "Gigi D'Agostino -Gigis Time EP".

- ^ "Giorgio Moroder: Godfather of Modern Dance Music". Time.

- ^ "Giorgio Moroder – Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic.

- ^ Evan Cater. "Philip Oakey & Giorgio Moroder: Overview". AllMusic. Retrieved 21 December 2009.

This record was a collaboration between Philip Oakey, the big-voiced lead singer of the techno-pop band the Human League, and Giorgio Moroder, the Italian-born father of disco who spent the '80s writing synth-based pop and film music.

- ^ "The Legacy of Giorgio Moroder, the "Father of Disco"". Blisspop. 27 August 2018.

- ^ Segel 1987, p. [page needed].

- ^ Paliotti 2001, p. [page needed].

- ^ It is claimed by some (Badger 1995) that the introduction to Europe of the syncopated sounds of early American jazz came in the form of music performed by the band of the 369th Infantry Regiment (the "Harlem Hellfighters"), led by James Reese Europe, the leading figure on the African American music scene in New York City in the 1910s before being commissioned as a lieutenant to serve in World War I.

- ^ Dave Laing with Olivier Julien and Catherine Budent, "Television Shows", pg. 475, in the Continuum Encyclopedia of Popular Music of the World

- ^ a b c Surian 2000, pp. 169–201.

- ^ Stokes 2003, p. 216.

- ^ Rapporto 2005 (in Italian). Economia della musica italiana del Centro Ask: dell’Università Bocconi.

- ^ "Chamber Opera Competition". Culturekiosque Publications. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014.

- ^ Boccardi 2001, p. [page needed].

- ^ Jeff Matthews. "Christmas (3)--Tu scendi dalle stelle, music (2)". Around Naples Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 25 February 2007. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- ^ Baroni 2005, p. 15

- ^ "Structure of Education System in Italy". EuroEducation.net. Retrieved 31 December 2006.

- ^ "Ministero dell'istruzione, dell'università e della ricerca, Indicazioni nazionali per i piani di studio personalizzati dei percorsi liceali – Piano degli studi e Obiettivi specifici di apprendimento – Allegato C/5 (Art. 2 comma 3) – Liceo musicale e coreutico" (PDF) (in Italian). Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 June 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006. annex to Circolare n.11 del 1 febbraio 2006 – Trasmissione decreti di attuazione del progetto di innovazione, in ambito nazionale, ex art. 11 del D.P.R. n. 275/1999 – Istituti di istruzione secondaria superiore – "Sistema educativo e nuovi ordinamenti". MIUR (in Italian). Archived from the original on 16 July 2006. Retrieved 12 October 2006.

- ^ "Telegramma del Presidente della Repubblica ai partecipanti e agli organizzatori di Verdincanto" [Telegram from the President of the Republic to the participants and organizers of Verdincanto] (in Italian). Rai Educational. Archived from the original on 24 September 2017.

References

[edit]- Adams, Walter (May 1939). "The Present Problem; Refugees in Europe". Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 203: 37–44. doi:10.1177/000271623920300105. S2CID 144435665.

- Badger, F. Reed (Spring 1989). "James Reese Europe and the Prehistory of Jazz". American Music. 7 (1): 48–67. doi:10.2307/3052049. JSTOR 3052049.

- Baldi, Edgardo (1935). "Mascagni, Puccini, Casella, Busoni, Toscanini". Enciclopedia Moderna Italiana (in Italian). Milan: Sonzogno.

- Baroni, Joseph (2005). Dizionario della Televisione (in Italian). Milan: Raffaello Cortina. ISBN 88-7078-972-1.

- Boccardi, Donald (2001). The History of American Catholic Hymnals Since Vatican II. Chicago: GIA Publications. ISBN 1-57999-121-1.

- Bordoni, Carlo; Testani, Gianluca (2006). Oggi ho salvato il mondo; Canzoni di protesta 1990-2005 (in Italian). Rome: Fazi ed. ISBN 88-7966-409-3.

- Bouget, Marie-Thérèse (1986). "Musical Enigmas in Ballet of the Court of Savoy". Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research. 4 (1). Translated by McGowen, M. Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, Vol. 4, No. 1: 29–44. doi:10.2307/1290672. JSTOR 1290672.

- Busoni, Ferruccio (1962). "Sketch for a New Esthetic of Music". Three Classics in the Aesthetics of Music. New York: Dover. ISBN 0-486-20320-4.

- Carpitella, Diego (1975). "Der Diaulos des Celestino". Musikforschung (in German) (18): 422–428. ISSN 0027-4801. cited in the Sorce Keller, Catalano & Colicci 1996, pp. 616.

- Charanis, Peter (1946). "On the Question of Hellenization of Sicily and Southern Italy During the Middle Ages". American Historical Review. 52 (1). The American Historical Review: 74–86. doi:10.2307/1845070. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1845070.

- di Giacomo, Salvatore (1924). I quattro antichi conservatori di musica a Napoli (The Four Ancient Music Conservatories of Naples) (in Italian). Milan: Sandron.

- Monti, Giangilberto; Di Pietro, Veronica (2003). Dizionario dei Cantautori (in Italian). Milan: Garzanti. ISBN 88-11-74035-5.

- Farmer, Henry George (1957). "The Music of Islam". Ancient and Oriental Music. New Oxford History of Music. Vol. 1. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-316301-2.

- Fazzini, Paolo (2006). Visioni sonore, Viaggi tra i compositori italiani per il cinema (in Italian). Roma: Un mondo a parte. ISBN 88-89481-06-4.

- Foil, David (1995). Gregorian Chant and Polyphony. New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1-884822-41-X.

- Friedland, Bea (January 1970). "Italy's Ottocento: Notes from the Musical Underground". The Musical Quarterly. 56 (1): 27–53. doi:10.1093/mq/LVI.1.27. ISSN 0027-4631.

- Giurati, Giovanni (1995). "Italian Ethnomusicology". Yearbook for Traditional Music. 27. This essay provides a thorough review of the history and current state of Italian ethnomusicology.

- Guizzi, Febo (1990). "Gli strumenti della musica poplare in Italia". Le tradizioni popolari: Canti e musiche popolari (in Italian). Milan: Electa.

- Guizzi, Febo (2002). Gli strumenti della musica popolare in Italia. Alia Musica. Vol. 8. Lucca: Libreria musicale italiana. ISBN 88-7096-325-X. Invaluable survey of popular instruments in use in Italy, ranging from percussion, wind and plucked instruments to various noise makers. Numerous drawings and plates. Wrappers.

- Fabio Lombardi, 1989, Mostra di strumenti musicali popolari romagnoli : Meldola Teatro Comunale G. A. Dragoni, 26–29 agosto 1989; raccolti da Fabio Lombardi nella vallata del bidente, Comuni di: Bagno di Romagna, S. Sofia, Meldola, Galeata, Forli, Civitella diR. e Forlimpopoli; presentazione Roberto Leydi. – Forli : Provincia di Forli, 1989. – 56 p. : ill.; 21 cm. In testa al front.: Provincia di Forli, Comune di Meldola.

- Fabio Lombardi, 2000, Canti e strumenti popolari della Romagna Bidentina, Società Editrice "Il Ponte Vecchio", Cesena

- Sorce Keller, Marcello; Catalano, Roberto; Colicci, Giuseppina (1996). "Italy". In Timothy Rice; James Porter; Chris Goertzen (eds.). Europe. Garland Encyclopedia of World Music. Vol. 8. Garland. pp. 604–625. ISBN 0-8240-6034-2.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (January 1984). "Folk Music in Trentino: Oral Transmission and the Use of Vernacular languages". Ethnomusicology. 28 (1): 75–89. doi:10.2307/851432. JSTOR 851432.

- Sorce Keller, Marcello (2014). "Italy in Music: A Sweeping (and Somewhat Audacious) Reconstruction of a Problematic Identity". In Franco Fabbri; Goffredo Plastino (eds.). Made in Italy. Studies in Popular Music. London: Routledge. pp. 17–28.

- Kramer, Jonathan (1999). "The Nature and Origins of Musical Postmodernism". Current Musicology. 66: 7–20. ISSN 0011-3735.

- Reprinted in Lochhead, Judy; Aunder, Joseph, eds. (2002). Postmodern Music/Postmodern Thought. Routledge. ISBN 0-8153-3820-1.

- Lanza, Andrea (2008). "An Outline of Italian Instrumental Music in the 20th Century". Sonus. A Journal of Investigations into Global Musical Possibilities. 29/1: 1–21.

- Leydi, Robert (1990). "Efisio Melis". Le tradizioni popolari: Canti e musiche popolari in Italia (in Italian). Milan: Edizioni Electa. ISBN 88-435-3246-4.

- Lomax, Alan (1956). "Folk Song Style: Notes on a Systematic Approach to the Study of Folk Song". Journal of the International Folk Music Council. 8 (VIII). Journal of the International Folk Music Council, Vol. 8: 48–50. doi:10.2307/834750. ISSN 0950-7922. JSTOR 834750.

- Lomax, Alan (1959). "Folk Song Style". American Anthropologist. 61 (6): 927–54. doi:10.1525/aa.1959.61.6.02a00030.

- Maiden, Martin (1994). A Linguistic History of Italian. London: Longman. ISBN 0-582-05928-3.

- Maiden, Martin (1997). The Dialects of Italy. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11104-8.

- Matthews, Jeff and David Taylor (1994). A Brief History of Naples and Other Tales. Naples: Fotoprogetti.

- Mazzoletti, Adriano (1983). Jazz in Italia. Dalle Origini al dopoguerra (in Italian). Rome: EDT. ISBN 88-7063-704-2.

- "Cimarosa and Ballo in maschera". Il Mondo della musica (in Italian). Milan: Sonzogno. 1956.

- Murolo, Roberto (1963). Napoletana, Anthologia cronologica della Canzone Partenopea (Recorded anthology). 12 LPs (re-released in 9 CDs) (in Italian). Milano: Durum.

- Sadie, Stanley, ed. (1995). New Grove Dictionary of Music & Musicians. London: Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 1-56159-174-2.

- Niccolodi, Fiamma (1984). Musica e musicisti nel ventennio fascista (in Italian). Fiesole: Discanto.

- Olson, Harry F. (1967). Music, Physics and Engineering (2nd ed.). New York: Dover reprint. LCCN 66028730.

- Paliotti, Vittorio (2001). Salone Margherita (in Italian). Naples: Altrastampa.

- Surian, Alessio (2000). "Tenores and Tarantellas". In Broughton, Simon; Ellingham, Mark; McConnachie, James; Duane, Orla (eds.). Rough Guide to World Music, Vol. 1: Africa, Europe and the Middle East. London: Rough Guides. pp. 189–201. ISBN 1-85828-636-0.

- Ricci, Antonella & Tucci, Roberto (October 1988). "Folk Musical Instruments in Calabria". The Galpin Society Journal. 41: 36–58. doi:10.2307/842707. JSTOR 842707.

- Sachs, Curt (1943). "The Road to Major". The Rise of Music in the Ancient World East and West. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-09718-8.

- Sachs, Harvey (2002). Toscanini. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80137-X.

- Sachs, Harvey (1987). Music in Fascist Italy. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79004-8.

- Sassu, Pietro (1978). La musica sarda (3 LPs and booklet) (in Italian). Milano: Albatros VPA 8150-52.

- Segel, Harold B. (1987). Turn-of-the-Century Cabaret: Paris, Barcelona, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Cracow, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Zurich. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231051286.