Avala

| Avala | |

|---|---|

| Авала | |

Мount Avala in February 2015 | |

| Highest point | |

| Peak | Žrnov |

| Elevation | 511 m (1,677 ft) |

| Coordinates | 44°41′20″N 20°30′58″E / 44.68902389°N 20.51602028°E |

| Naming | |

| English translation | Obstacle, shelter |

| Language of name | Serbian |

| Geography | |

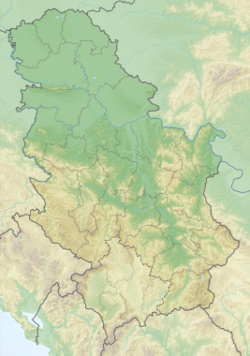

Avala (Serbian Cyrillic: Авала, pronounced [âv̞ala]) is a mountain in Serbia, overlooking Belgrade. It is situated in the south-eastern corner of the city and provides a great panoramic view of Belgrade, Vojvodina and Šumadija, as the surrounding area on all sides is mostly lowlands. It stands at 511 metres (1,677 ft) above sea level, which means that it enters the locally defined mountain category just by 11 m (36 ft).

Location

[edit]Avala is located 16 km (9.9 mi)[1] south-east of downtown Belgrade. The entire area of the mountain belongs to the Belgrade City area, the majority of it being in the municipality of Voždovac, with the eastern slopes being in the municipality of Grocka, and the southernmost extension in the municipality of Sopot. It is possible that in the future the entire area of Avala would create a separate municipality of Belgrade, named Avalski Venac.

Geography

[edit]Avala is a low type of the Pannonian island mountain, though it is actually the northernmost mountain in Šumadija. Until 600,000 years ago, when the surrounding low areas were flooded by the inner Pannonian Sea, Avala was an island, just as the neighboring mountains (Kosmaj, Fruška Gora, etc.), thus earning its geographical classification. However, Avala remains an "island mountain" as the area around it, Pinosava plateau of the northern Low Šumadija, is low and mostly flat. In the north it extends into the woods of Stepin Lug.

The mountain is built of serpentinite, limestone and magmatic rocks, which are injected in the shape of cone (laccolith). Other peaks include Ladne vode (340 m (1,120 ft)), Zvečara (347 m (1,138 ft)), Sakinac (315 m (1,033 ft)). The Avala had deposits of ores, most notably lead and mercury's ore of cinnabarite and mining activities which can be traced to the pre-Antiquity times.[2] Other metals mined on the mountain include silver, gold and zinc. At the Šuplja Stena localities, seven quartz-carbonate veins with minerals and cinnabarite ore were discovered (Šuplja Stena, Dževerov Kamen, Dževerov Potok, Rupine, Kamenik-Spomenik, Kamenik and Prečica), with 13 additional between Šuplja Stena and Topčiderka river.[3]

Avala is also a location where the mineral avalite, named after the mountain, was found. A greenish mineral, chromian, magnesian or potassic alumosilicate (variety of the mineral illite), it was discovered by Serbian chemist Sima Lozanić who established its formula. Optically examined by the Israeli mineralogist Tamir Grodek who classified it as a member of the mica mineral group.[4]

On the southern slopes, in the area of Ripanj, the closed Tešićev Majdan ("Tešić Quarry") is located. The stone pit was privately owned, but was confiscated by the state after World War II and stopped operating before 1960. In the process of restitution after 2000, the quarry was returned to the surviving owners, but they live abroad so the quarry is still not operational. It is the only known location of kersantite in Serbia, a rare type of greenish granite. For decades, kersantite was used for Belgrade buildings. Features built with this stone include the fountain between the Novi Dvor and Stari Dvor, the bordure of the Hotel Bristol, Small Staircase in Kalemegdan Park, pedestal of the Play of Black Horses statues in front of the House of the National Assembly of Serbia and buildings of Belgrade Cooperative, Elementary School King Petar I, Cathedral Church of St. Michael the Archangel and Main Post Office Building. As the buildings began to deteriorate over time, city authorities showed interest in the quarry, not only for the repairs but also for future construction. For now, when some deteriorated kersantite feature has to be replaced, the artificial stone is used (as in the case of the pedestal of the Play of Black Horses). Geologists suggested to the city to obtain the ownership over the land on which the pit is located and to reopen it. The Belgrade City government announced in 2012 that it will unilaterally explore the pit until it gets reopened and inspected it in 2013. Large amounts of already cut kersantite were found. Locals have been illegally extracting the stone and crushing it to use as road cover.[5] After the political change in Belgrade in late 2013, the motion was dropped.

On the mountain itself, there are several springs, of which Sakinac is best known.[1] Despite being the only mountain in the area, Avala is not a source of many rivers. The Topčiderka river, originating in the woods of Lipovička šuma on the south-west, flows on the western slopes of Avala, while the river Bolečica flows on the eastern slopes. Other minor flows include the Vranovac, a tributary to the Bolečica. A small artificial lake near the village of Pinosava was created on the western slope of the mountain. The settlements in the area are notorious for problems with shortages of drinking water during summer.

Wildlife

[edit]Protection

[edit]

The mountain has been protected since 1859[6] as a natural monument, or, by the modern standards, "sight of the exquisite values". That year, Serbian ruling prince Miloš Obrenović issued an order for the Avala to get fenced and protected that way.[7] He also banned construction of houses on the mountain itself.[8]

In the early 20th century, plans were made for further forestation of the mountain. In his last visit to Serbia in 1903, Austro-Hungarian naturalist Felix Philipp Kanitz noted that the mountain would become "another exceptional excursion area", after the Topčider park.[8] Remains of the medieval Žrnov were removed in 1934 to make way for the Monument to the Unknown Hero. The destruction of Žrnov, which was demolished with dynamite, caused massive discontent among the citizens of Belgrade.[7] In the period of the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, the mountain was declared a national park, in 1936. In 1946, by the ukaz of the Presidium of the National Assembly of Serbia, Avala was reduced to the status of the "public property of general benefit" and placed under direct management of the Government of Serbia.

Despite being officially protected for almost 150 years, it was only in 2007 that preservation plans for the mountain were made. That way, Avala entered a circle of protected green areas of Belgrade, which also included the mountain of Kosmaj, the island of Veliko Ratno Ostrvo and the woods of Stepin Lug, with the forests of Košutnjak and Topčider to be added next. Protected areas of Avala spread over 48,913 hectares (120,870 acres)

Some areas within the mountain are additionally protected., including the "Complex of mountain beech, oak, maple and elm", which is in the first level of protection. It is located in the valley of the Vranovica stream, close to the "Čarapićev Brest" visitors' complex.[8]

In early September 2020, unknown persons began clearing the field in the protected downhill of Avala. The field was a recorded habitat of Caspian whipsnake. Illegal construction of the complex of houses, without any permits, began in January 2021. Inspections closed it, but the construction continued before it was halted.[9] Demolition of the complex began in August 2022.[10]

Plant life

[edit]Avala is known for its diverse plant life, despite not being a tall mountain. There are over 600 plant species living on the mountain. Some of them are protected by the law as natural rarities, like certain types of laburnum, box tree, black broom, common holly and martagon lily.[1] The area is also abundant in medicinal herbs, like the early-purple orchid and belladonna. Almost 70% of Avala is forested,[11] or 5.01 square kilometres (1.93 sq mi).[12] Thus, the meadow plant communities are rare. Other protected plant species include common yew and oregano.[13] High woods mostly consist of durmast oak, Turkey oak, hornbeam, beech, linden, black pine, black locust and other trees.

Animal life

[edit]Almost 100 species of birds live on Avala, including strictly protected Eurasian sparrowhawk, European honey buzzard and European green woodpecker.[11] Total of 21 bird species is protected. Other species include common buzzard, stock dove, common kestrel, and Eurasian scops owl.[13]

A section of the mountain is organized as a game hunting ground.[14]

Name

[edit]

In the Middle Ages, the town of Žrnov or "Avalski Grad" (Avala town) was located on top of Avala. In 1442. it was conquered by the Ottoman Empire, which built a new town in Žrnov's place as a counter-fortress to the Belgrade city fort, and renamed it "havale", which originally comes from Arabic and means "obstacle" or "shelter".

Human history

[edit]Mining

[edit]Archeologist Miloje Vasić believed that the vast mines of cinnabarite (mercury-sulfide) on Avala were crucial for the development of the Vinča culture, on the banks of the Danube circa 5700 BC. Settlers of Vinča apparently melted cinnabarite and used it in metallurgy.[2] Mining was active on the mountain at 3000 BC.[15] However, it is still contested when people began mining on Avala, from the Neolithic, to the earnest mining by the Celtic Scordisci, prior to Roman conquest. There are three major mines, Šuplja Stena, Crveni Breg and Ciganlija, the first being the most explored.[3]

Vasić also claimed that Vinča hosted a Ionian trade colony from the Aegean around 6000 BC, and that Ionian seamen discovered primitive mine in Šuplja Stena. The Ionians continued to mine cinnabarite and with their final departure from Vinča, the mine stoppe working until being partially revived by the Celts. Pots with mercury were discovered in Šuplja Stena, but not the smelting artefacts or slag. A vast number of potteries discovered in Vinča was internally glazed with cinnabarite, with some quartz and phyllosilicates. Examination showed that it matches materials from Avala. Vinča developed c.5700 BC, Vladimir Milojević claim the production for certain from 2000 BC to 750 BC without being able to say when the mining began. Remains from both the Neolithic and the last Ice Age are also discovered in the cave.[3][16]

It is still debated whether Šuplja Stena is a natural cave or was completely dug for the mining purposes. Remains of the Neanderthal culture were discovered in it. In his 1943 Prehistoric mine Šuplja Stena on Avala hill near Belgrade (Serbia), Vladimir Milojčić said that the "cave is old as Avala", formed by the volcanic activity and elevation of the terrain. The cave was first used by the wild animals and later by the prehistoric peoples, with animal and human remains, and prehistoric mining artefacts have been discovered. However, geographer Dragan Petrović in his work on the caves of Šumadija, lists caves on the present Belgrade's territory, but makes no mention of Šuplja Stena.[3]

In Medieval Serbia mining on Avala began in c.1420, after the Law on mines was issued by the Despot Stefan Lazarević in 1412.[17] In this period, the cinnabarite was used for fresco paintings and was exported to Greece.[18] Mining activities ceased by the 1960s, when the last two mines, Šuplja Stena and Crveni Breg, were closed.[1] Šuplja Stena ("Hollow Boulder") was a mercury mine while in Crveni Breg ("Red Hill"), lead, zinc, silver and gold were extracted. Crveni Breg was closed in 1953 and has traces of the usage from the Roman period. It has seven levels, out of which four are flooded, and the stalactites are being formed inside. By 2009 the upper level was prepared for visitors, having been cleaned and lighted for some 300 m (980 ft), but the project of turning it into a tourist attraction failed.[19]

The survey of the Crveni Breg began in 1870, and the mine was opened in 1886. Lead, zinc and silver were mined. It was intermittently operational till 1901 when it was purchased by the Belgian company from the previous Serbian owners. Operational again from 1902, it was sold to the French owners in 1906. It worked until 1941, and in this period 18,800 tons of ore was extracted. It was reopened in 1948 and closed in 1953. 55,000 tons of ore was extracted in this period, containing lead, zinc, silver, gold and copper. Along the road to Mladenovac there is the Ciganlija mine, with numerous smaller horizontal pits covered with overgrowth. Next to the mine is Zavljak stream, where remains of the slag dated to Antiquity were discovered. The slag contains lead, zinc, copper and silver.[3]

The ore in Šuplja Stena was rediscovered in 1882, and in 1883 survey began with digging of the "Jerina" horizontal pit. By 1886, horizontal pit "Prečica" with smelters, was also finished. During this period, numerous pits and shafts were dug, with 7 km (4.3 mi) being dug only in 1891. From 1884 to 1889 it was majority owned by Đorđe Vajfert, when he sold it to an English firm, but continued to manage works. The ore was exported to Vienna, London and China. Though officially closed in 1893, the mine was extracting ore only from 1887 to 1891. From 1889 to 1890 some 30 tons of mercury was sold. The survey of Šuplja Stena was continued in 1910 and, with interruptions, lasted until 1959, while the preparatory works for the reopening began in 1967. Smelters was built, the production continued in 1968 and until spring 1972 when it was finally closed, the mine produced 80 tons of mercury. Mine in Šuplja Stena is considered one of the best explored one, in geological, chemical, mineralogical and mining sense.[3]

World War II and later

[edit]Avala was a key point during the Belgrade Offensive in October 1944, a fighting for the liberation of Belgrade in World War II. Germans halted their mechanized units along the Smederevo road, at Mali Mokri Lug, continued equipped with the light weapons and spread over Avala. German units were commanded by lieutenant general Walter Stettner, who was killed during the battle. Germans also had a 7th SS division at the mountain, but after the joint attack of Yugoslav Partisans and Red Army, Belgrade was liberated on 20 October 1944.[20]

In 1965, a 202-metre-high (663 ft) Avala TV Tower was constructed, one of the tallest structures in the Balkans, by the architects Uglješa Bogunović, Slobodan Janjić and M. Krstić. It had a restaurant look-out on 120 m (390 ft). The tower was destroyed during the NATO bombing of Serbia in 1999. Its total reconstruction began in 2006 and was officially opened at a ceremony on 21 April 2010. The new tower is almost the exact replica of the destroyed one, including the unique three-feet base. Belgrade's General Urbanistic Plan (GUP) for the 2001–2021 period defines the mountain as a sports and recreation area.

During the 1972 Yugoslav smallpox outbreak, Avala functioned as a quarantine. The patients were first placed in the mountaineering camp "Čarapićev Brest", which was adapted into the ad-hoc hospital. The patients were later relocated closer to the main road, in the "1000 Ruža" motel.[21]

The 1st Air Defense Missile Battalion, one of the "Neva" battalions of the 250th Air Defense Missile Brigade, is located in Zuce, on the eastern slopes of Avala.[22]

Settlements

[edit]Settlements near the mountain are not much populous. They include Ripanj (on the south, the largest one, with a population of 10,084 by the 2022 census of population), Pinosava (on the west, 3,239), Zuce (on the north-east, 1,915), Beli Potok (on the north, 3,717), all in the municipality of Voždovac, and Vrčin (on the east, 8,601), in the municipality of Grocka.

Administration

[edit]A movement for creation of the new Belgrade's municipality called Avalski Venac originated in 1996. A motion for the recreation of the municipality of Ripanj appeared in 2002. The idea was to split municipality of Voždovac of its distant, suburban settlements in the area of the Avala: Ripanj, Beli Potok, Pinosava and Zuce.[23] Later, a motion for Vrčin to split from the municipality of Grocka and creation of a joint sub-Avalan municipality also appeared. If created, the new municipality would have a population of 27,556 in 2022. In September 2007 an official motion was started by the municipality of Voždovac to create this new municipality, which would also include Resnik from the municipality of Rakovica[24][25][26] Supported by the local administration headed by the Democratic Party at the time, it was blocked by the members of the same party on the city level. It was also proposed by the political party G17 Plus in 2010[27] and Nova Stranka in 2015.[28] Coalition Moramo, during the April 2022 campaign for the local elections in Belgrade, favored formation of the municipality, but also of several others.[29]

Transportation

[edit]Avala is well connected with Belgrade and other parts of Serbia via roads, highway and railroads.

Avalski drum ("Avala road") is an extension of the Boulevard of the Liberation, which directly connects the mountain to downtown Belgrade (via neighborhoods of Selo Rakovica, Jajinci, Banjica, Voždovac, Autokomanda, Karađorđev Park and Slavija). On the mountain, Avalski drum divides in three:

- one section is a circular road which goes to the top of the mountain.

- second section continues to the south-west, through Ripanj, Lipovička Šuma and Barajevo, and makes a connection to the major road in the western Serbia, Ibarska magistrala.

- third section goes south-east, parallel to the highway, through Trešnja and Ralja and further to the south and east (where it meets the highway).

Sub-Avalan settlements are directly connected to Belgrade by the bus lines of the city's public transportation, with terminus in the Belgrade's neighborhood of Trošarina.

The Belgrade–Niš highway, a section of one of the major European roads, European route E75, runs east of the mountain, through Vrčin. North of the mountain runs Kružni put, the most important road in the southern outskirts of Belgrade, which connects all the southern sections of the city. It is also a projected route of the future Belgrade beltway which would continue through the Bolečica river valley and the projected Vinča-Omoljica bridge over the Danube into Vojvodina.

Railroads also run on both sides of the mountain. Eastern branch is a section of the Belgrade-Niš railroad. It runs through the tunnel under the Avala at Beli Potok and then through Včrin. Western branch runs through Ripanj and the long "Ripanj tunnel" (though not under the Avala), and continues into western Serbia and further into Montenegro, as part of the Belgrade–Bar railway.

Tourism

[edit]

Avala is a traditional picnic resort for Belgraders, but its capacities are not being used much. In 1984 number of tourists was only 15,700 despite over 1.5 million of inhabitants in Belgrade. Some attractions and capacities on the mountain include:

- Šuplja Stena, a former very popular children's resort, located on the mountain's wind rose; after the 1990s it turned into a residential place refugees from the Yugoslav Wars but was reconstructed and reopened in 2012;

- Avala Tower, landmark TV Tower that was destroyed during the 1999 NATO bombing of Serbia, later rebuilt in 2010; In June 2017 the tourist complex was opened at the base of the tower. It includes, among other facilities, a restaurant, ethno-gallery, souvenir shop, sports fields and outdoor gym.[30]

- Weekend-settlement on the southern slopes;

- Motel "1000 Ruža" in Beli Potok; now adapted into the 3-star hotel;

- Hotel "Avala"; built in 1928 by the Russian architect Viktor Lukomsky. Russian sculptor Aleksandr Zagrodnyuk sculpted two sphinx which are located at the hotel's north side, on the staircase to the hotel's terrace. The hotel was privatised in 2005, but in 2007 it was declared a cultural monument;[1]

- Trešnja resort, in the southernmost extension of the mountain;

- Mountaineering camp of Čarapićev brest; Projected by the architect Slobodan Mihajlović in the 1960s, on the northern slopes of the Avala, above Beli Potok. It was renovated in 2003;[1]

- Mountaineering camp of Mitrovićev dom. It was made of wood and stone and named (“Mitrović Home”) after dr Dušan Špirta Mitrović, a medical doctor and volunteer on the Salonika front. In 1981 it was declared a cultural monument but in 2014 it burned to the ground in the fire. In 2016–17 it was reconstructed to look exactly the same way it looked before the fire.[1]

- One of only three officially designated campsites in Belgrade by 2018 is located on the mountain. A small camping ground, it is situated on the slopes in the Ripanj section.[31]

- Hiking trail "Sakinac", fully revitalized in September 2020. Formerly paved with asphalt concrete, it is covered with the crushed stone from Struganik. It connects the Sakinac water spring to the Mitrovićev dom, on the top of the mountain. There, it forks in two, one end reaching the tower while the other leads to the church.[32]

Monuments on Avala

[edit]Special attractions of the Avala are several monuments. They include:

- Monument to the Unknown Hero – dedicated to the unknown Serbian soldier from World War I; sculptured by Ivan Meštrović in the form of mausoleum with 8 caryatides (columns shaped like female figures, in this case each one representing a woman from a different historical region of Yugoslavia), it was completed in 1938. An earlier monument was erected in 1915 at the location by the German soldiers, on the orders of Field marshal August von Mackensen.

- Monument to the Soviet war veterans – dedicated to the members of the Soviet military delegation which died in an airplane crash on the Avala on October 19, 1964. They were flying to Belgrade for the celebration of the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Belgrade in World War II, October 20, 1944, as Red Army forces participated in the expulsion of Germans. Among those killed in the crash were Marshal Sergey Semyonovich Biryuzov, chief of the General Staff and first deputy defense minister of the Soviet Union and General Vladimir Ivanovich Zhdanov. The monument was sculptured by Jovan Kratohvil.

- Memorial Park – dedicated to the victims of the World War II

- Monument to Vasa Čarapić – dedicated to Vasa Čarapić, one of the leaders of the First Serbian Uprising in 1804 and liberator of Belgrade from the Turks, built in Beli Potok, his birthplace, near the mountaineers home Čarapićev brest. It was sculptured in 1991 by Dušan Nikolić.

Churches

[edit]Small church dedicated to the Saint Despot Stefan Lazarević was built in the immediate vicinity of the Avala Tower and Monument to the Unknown Hero. The foundations were consecrated by the Patriarch of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Irinej, in 2015. Made of white pine and designed by deacon Miroslav Nikolić, it covers only 50 m2 (540 sq ft). The bell tower, built next to the church, is also made of wood. The church contains epitrachelion of Saint Nectarios of Aegina and pillow of Saint Petka.[33]

Mountaineering camp

[edit]Annually, from July 1 until July 10, a traditional camp of Serbian mountaineers is held on the Avala. Among other mountaineering activities, there are competitions in:

- Orienteering

- Climbing (on an outdoor Climbing wall)

- Mountain biking

- Mountain running

Ski center

[edit]The first skiing competition in Yugoslavia was held on Avala in 1929.[34][35] In 1934, Belgrade was declared a national ski center, and by 1936 there were ski pistes and a 20 m (66 ft) ski jumping hill. A special bus line was organized from Slavija to the ski structures on the mountain.[36]

The first local, Serbian competition after World War II was also held here, in 1946. The usual route was the one starting at the logger's cabin and ending all the way to the foothills above Ripanj. The tracks were quite crude. Despite low altitude, construction of the ski resort, with sports and recreational venues and a cable car have been proposed in 1994 and 2005. In October 2018, city government announced plans to set a 550 m (1,800 ft) long piste. The construction of the complex, which is planned to be operational over the entire year thanks to the artificial snowing system (skiing specifically from November to February), should start in 2019. The piste will start in the immediate vicinity of the tower and end at the logger's cabin. Due to the altitude and the climate, the north-western slope, in the direction of Pinosava, is chosen. The track has been labeled as the "blue", which means it is of and intermediate level of difficulty.[34][35]

Phase I includes the construction of the piste, ski lift, training trail, snowmaking cannons, decorative lights, parking lots and special machinery. Phase II comprises the building of the bobsled on rails track, zip-line, mini golf course, artificial climbing rock, children playground and an adventure park. Projected price is €5 million.[34][35] As the project includes cutting of the mountain forest, the opposition to the project amounted and no works began before 2020.[37]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Marija Brakočević (13 November 2016), "Avala – lepotiva Beograda: Zaboravljena planina", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ a b Srpska enciklopedija, Vol. II, page 142-143. Matica Srpska, Srpska akademija nauka i umetnosti, Zavod za udžbenike. 2013. ISBN 978-86-7946-121-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Branka Vasiljević (9 July 2023). Руду са Авале куповали у Бечу, Лондону и Кини [Merchants from Vienna, London and China purchased ores from Avala]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Srpska porodična enciklopedija, Vol. I, "Narodna knjiga" & "Politika", 2006, ISBN 86-331-2730-X

- ^ Marija Brakočević (27 October 2013), "Malo stepenište na Kalemegdanu čeka beogradski kamen", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ J.Lucić (29 March 2008), "Avala – predeo izuzetnih odlika", Politika (in Serbian), p. 23

- ^ a b Staniša B. Jovanović, "Detaljnije o Avali", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ a b c Andreja Dodić (24 March 2021). "Graditeljsko divljaštvo na Avali" [Construction savagery on Avala]. Politika (in Serbian). pp. 24–25.

- ^ FoNet (16 July 2022). "Još se ne zna šta će biti sa nelegalnim objektima u zaštićenom području na Avali" [Still not known what will happen to illegal structured in the protected area of Avala]. N1 (in Serbian).

- ^ Ana Vuković (24 August 2022). Обрачун са комуналним и урбанистичким дивљањем [Fighting communal and urban rampage]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ a b Vladimir Vukasović (9 July 2013), "Prestonica dobija još devet prirodnih dobara", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Anica Teofilović; Vesna Isajlović; Milica Grozdanić (2010). Пројекат "Зелена регулатива Београда" - IV фаза: План генералне регулације система зелених површина Београда (концепт плана) [Project "Green regulations of Belgrade" - IV phase: Plan of the general regulation of the green area system in Belgrade (concept of the plan)] (PDF). Urbanistički zavod Beograda. p. 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2022-01-15. Retrieved 2022-01-16.

- ^ a b Branka Vasiljević (3 April 2022). У престоници заштићено 40 споменика природе [40 natural monuments protected in the capital]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (5 August 2018). "Lovci u Beograd stižu porodično" [Hunters travel to Belgrade with their families]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (17 March 2019). Истраживач лагума [Explorer of the underground]. Politika-Magazin, No. 1120 (in Serbian). pp. 6–7.

- ^ Vladimir J. Fewkes. On the interpretation and dating of the site of Belo Brdo at Vinča in Yugoslavia.

- ^ Novak Bjelić (30 Mar 2018). "Казивања о "Трепчи": 1303–2018 – Рудници под једном капом" [Tales of "Trepča": 1303–2018 – Mines under one administration]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 20.

- ^ Branka Jakšić (24 September 2017), "Pogled s neba i podzemne avanture", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Marija Brakočević (29 May 2009), "Rudnik na Avali čeka posetioce", Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Dimitrije Bukvić (21 October 2018). "Noć kad se usijalo nebo nad Beogradom" [The night when the sky above Belgrade incandescent]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 08.

- ^ Desanka Kosanović Ćetković (13 May 1972). Како је било у карантину "Чарапића брест" [What was it like in the "Čarapića Brest" quarantine]. Politika (reprint on 13 May 2022) (in Serbian). p. 16.

- ^ Milan Galović (31 December 2021). "Raketaši s Avale čuvaju nebo Beograda" [Rocketmen from Avala guard Belgrade's sky]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ^ Dejan Aleksić (8 October 2017), "Dug i skup put do novih opština" [Long and costly road to the new municipalities], Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Politika, 4 November 2007, p.23

- ^ Politika, 20 October 2007, p.27

- ^ Politika, 29 October 2007, p.27

- ^ Slobodan Kljakić (2 August 2010), "Od šest kvartova do sedamnaest opština" [From six quarters to seventeen municipalities], Politika (in Serbian)

- ^ Nova Stranka (21 January 2015). "Predlog izmene statute Beograda" [Proposition on change of the Belgrade statute] (in Serbian).

- ^ N1 Beograd (27 March 2022). "Veselinović: Batajnica će postati nova beogradska opština" [Veselinović: Batajnica will become new Belgrade's municipality]. N1 (in Serbian).

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ana Vuković (10 June 2017), "Kompleks na Avali dobio novi izgled", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- ^ Ana Vuković (16 August 2018). "Kamping turizam – neiskorišćena šansa" [Camping tourism – missed chance]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 14.

- ^ Нова пешачка стаза "Сакинац" на Авали [New hiking trail "Sakinac" on Avala]. Politika (in Serbian). 22 September 2020. p. 14.

- ^ Branka Vasiljević (10 May 2020). Hramovi od drveta sačuvali veru [Wooden temples preserved faith]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ a b c Ana Vuković (14 October 2018). "Avala izlazi na crtu Kopaoniku" [Avala dares Kopaonik]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ a b c Ana Vuković (4 March 2019). Скијање под Авалским торњем [Skiing under the Avala tower]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ^ Goran Vesić (18 August 2023). "Авала као прво скијалиште" [Avala as the first skiing ground]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 17.

- ^ Ana Vuković (16 December 2019). Ски-стаза на Авали још није на видику [Ski-trail on Avala nowhere in sight]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

Sources

[edit]- Mala Prosvetina Enciklopedija, Third edition (1986), Vol.I; Prosveta; ISBN 86-07-00001-2

- Jovan Đ. Marković (1990): Enciklopedijski geografski leksikon Jugoslavije; Svjetlost-Sarajevo; ISBN 86-01-02651-6

- Turističko područje Beograda, "Geokarta", 2007, ISBN 86-459-0099-8

External links

[edit]- Mountaineering camp on Avala (in Serbian)