Camouflage

Camouflage is the use of any combination of materials, coloration, or illumination for concealment, either by making animals or objects hard to see, or by disguising them as something else. Examples include the leopard's spotted coat, the battledress of a modern soldier, and the leaf-mimic katydid's wings. A third approach, motion dazzle, confuses the observer with a conspicuous pattern, making the object visible but momentarily harder to locate. The majority of camouflage methods aim for crypsis, often through a general resemblance to the background, high contrast disruptive coloration, eliminating shadow, and countershading. In the open ocean, where there is no background, the principal methods of camouflage are transparencying, silveringing, and countershading, while the ability to produce light is among other things used for counter-illumination on the undersides of cephalopods such as squid. Some animals, such as chameleons and octopuses, are capable of actively changing their skin pattern and colors, whether for camouflage or for signalling. It is possible that some plants use camouflage to evade being eaten by herbivores.

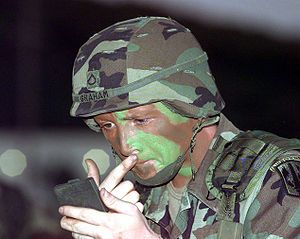

Military camouflage was spurred by the increasing range and accuracy of firearms in the 19th century. In particular the replacement of the inaccurate musket with the rifle made personal concealment in battle a survival skill. In the 20th century, military camouflage developed rapidly, especially during the First World War. On land, artists such as André Mare designed camouflage schemes and observation posts disguised as trees. At sea, merchant ships and troop carriers were painted in dazzle patterns that were highly visible, but designed to confuse enemy submarines as to the target's speed, range, and heading. During and after the Second World War, a variety of camouflage schemes were used for aircraft and for ground vehicles in different theatres of war. The use of radar since the mid-20th century has largely made camouflage for fixed-wing military aircraft obsolete.

Non-military use of camouflage includes making cell telephone towers less obtrusive and helping hunters to approach wary game animals. Patterns derived from military camouflage are frequently used in fashion clothing, exploiting their strong designs and sometimes their symbolism. Camouflage themes recur in modern art, and both figuratively and literally in science fiction and works of literature.

History

[edit]

In ancient Greece, Aristotle (384–322 BC) commented on the colour-changing abilities, both for camouflage and for signalling, of cephalopods including the octopus, in his Historia animalium:[1]

The octopus ... seeks its prey by so changing its colour as to render it like the colour of the stones adjacent to it; it does so also when alarmed.

— Aristotle[1]

Camouflage has been a topic of interest and research in zoology for well over a century. According to Charles Darwin's 1859 theory of natural selection,[2] features such as camouflage evolved by providing individual animals with a reproductive advantage, enabling them to leave more offspring, on average, than other members of the same species. In his Origin of Species, Darwin wrote:[3]

When we see leaf-eating insects green, and bark-feeders mottled-grey; the alpine ptarmigan white in winter, the red-grouse the colour of heather, and the black-grouse that of peaty earth, we must believe that these tints are of service to these birds and insects in preserving them from danger. Grouse, if not destroyed at some period of their lives, would increase in countless numbers; they are known to suffer largely from birds of prey; and hawks are guided by eyesight to their prey, so much so, that on parts of the Continent persons are warned not to keep white pigeons, as being the most liable to destruction. Hence I can see no reason to doubt that natural selection might be most effective in giving the proper colour to each kind of grouse, and in keeping that colour, when once acquired, true and constant.[3]

The English zoologist Edward Bagnall Poulton studied animal coloration, especially camouflage. In his 1890 book The Colours of Animals, he classified different types such as "special protective resemblance" (where an animal looks like another object), or "general aggressive resemblance" (where a predator blends in with the background, enabling it to approach prey). His experiments showed that swallow-tailed moth pupae were camouflaged to match the backgrounds on which they were reared as larvae.[4][a] Poulton's "general protective resemblance"[6] was at that time considered to be the main method of camouflage, as when Frank Evers Beddard wrote in 1892 that "tree-frequenting animals are often green in colour. Among vertebrates numerous species of parrots, iguanas, tree-frogs, and the green tree-snake are examples".[7] Beddard did however briefly mention other methods, including the "alluring coloration" of the flower mantis and the possibility of a different mechanism in the orange tip butterfly. He wrote that "the scattered green spots upon the under surface of the wings might have been intended for a rough sketch of the small flowerets of the plant [an umbellifer], so close is their mutual resemblance."[8][b] He also explained the coloration of sea fish such as the mackerel: "Among pelagic fish it is common to find the upper surface dark-coloured and the lower surface white, so that the animal is inconspicuous when seen either from above or below."[10]

The artist Abbott Handerson Thayer formulated what is sometimes called Thayer's Law, the principle of countershading.[11] However, he overstated the case in the 1909 book Concealing-Coloration in the Animal Kingdom, arguing that "All patterns and colors whatsoever of all animals that ever preyed or are preyed on are under certain normal circumstances obliterative" (that is, cryptic camouflage), and that "Not one 'mimicry' mark, not one 'warning color'... nor any 'sexually selected' color, exists anywhere in the world where there is not every reason to believe it the very best conceivable device for the concealment of its wearer",[12][13] and using paintings such as Peacock in the Woods (1907) to reinforce his argument.[14] Thayer was roundly mocked for these views by critics including Teddy Roosevelt.[15]

The English zoologist Hugh Cott's 1940 book Adaptive Coloration in Animals corrected Thayer's errors, sometimes sharply: "Thus we find Thayer straining the theory to a fantastic extreme in an endeavour to make it cover almost every type of coloration in the animal kingdom."[16] Cott built on Thayer's discoveries, developing a comprehensive view of camouflage based on "maximum disruptive contrast", countershading and hundreds of examples. The book explained how disruptive camouflage worked, using streaks of boldly contrasting colour, paradoxically making objects less visible by breaking up their outlines.[17] While Cott was more systematic and balanced in his view than Thayer, and did include some experimental evidence on the effectiveness of camouflage,[18] his 500-page textbook was, like Thayer's, mainly a natural history narrative which illustrated theories with examples.[19]

Experimental evidence that camouflage helps prey avoid being detected by predators was first provided in 2016, when ground-nesting birds (plovers and coursers) were shown to survive according to how well their egg contrast matched the local environment.[20]

Evolution

[edit]As there is a lack of evidence for camouflage in the fossil record, studying the evolution of camouflage strategies is very difficult. Furthermore, camouflage traits must be both adaptable (provide a fitness gain in a given environment) and heritable (in other words, the trait must undergo positive selection).[21] Thus, studying the evolution of camouflage strategies requires an understanding of the genetic components and various ecological pressures that drive crypsis.

Fossil history

[edit]Camouflage is a soft-tissue feature that is rarely preserved in the fossil record, but rare fossilised skin samples from the Cretaceous period show that some marine reptiles were countershaded. The skins, pigmented with dark-coloured eumelanin, reveal that both leatherback turtles and mosasaurs had dark backs and light bellies.[22] There is fossil evidence of camouflaged insects going back over 100 million years, for example lacewings larvae that stick debris all over their bodies much as their modern descendants do, hiding them from their prey.[23] Dinosaurs appear to have been camouflaged, as a 120 million year old fossil of a Psittacosaurus has been preserved with countershading.[24]

Genetics

[edit]Camouflage does not have a single genetic origin. However, studying the genetic components of camouflage in specific organisms illuminates the various ways that crypsis can evolve among lineages.

Many cephalopods have the ability to actively camouflage themselves, controlling crypsis through neural activity. For example, the genome of the common cuttlefish includes 16 copies of the reflectin gene, which grants the organism remarkable control over coloration and iridescence.[25] The reflectin gene is thought to have originated through transposition from symbiotic Aliivibrio fischeri bacteria, which provide bioluminescence to its hosts. While not all cephalopods use active camouflage, ancient cephalopods may have inherited the gene horizontally from symbiotic A. fischeri, with divergence occurred through subsequent gene duplication (such as in the case of Sepia officinalis) or gene loss (as with cephalopods with no active camouflage capabilities).[26][3] This is unique as an instance of camouflage arising as an instance of horizontal gene transfer from an endosymbiont. However, other methods of horizontal gene transfer are common in the evolution of camouflage strategies in other lineages. Peppered moths and walking stick insects both have camouflage-related genes that stem from transposition events.[27][28]

The Agouti genes are orthologous genes involved in camouflage across many lineages. They produce yellow and red coloration (phaeomelanin), and work in competition with other genes that produce black (melanin) and brown (eumelanin) colours.[29] In eastern deer mice, over a period of about 8000 years the single agouti gene developed 9 mutations that each made expression of yellow fur stronger under natural selection, and largely eliminated melanin-coding black fur coloration.[30] On the other hand, all black domesticated cats have deletions of the agouti gene that prevent its expression, meaning no yellow or red color is produced. The evolution, history and widespread scope of the agouti gene shows that different organisms often rely on orthologous or even identical genes to develop a variety of camouflage strategies.[31]

Ecology

[edit]While camouflage can increase an organism's fitness, it has genetic and energetic costs. There is a trade-off between detectability and mobility. Species camouflaged to fit a specific microhabitat are less likely to be detected when in that microhabitat, but must spend energy to reach, and sometimes to remain in, such areas. Outside the microhabitat, the organism has a higher chance of detection. Generalized camouflage allows species to avoid predation over a wide range of habitat backgrounds, but is less effective. The development of generalized or specialized camouflage strategies is highly dependent on the biotic and abiotic composition of the surrounding environment.[32]

There are many examples of the tradeoffs between specific and general cryptic patterning. Phestilla melanocrachia, a species of nudibranch that feeds on stony coral, utilizes specific cryptic patterning in reef ecosystems. The nudibranch syphons pigments from the consumed coral into the epidermis, adopting the same shade as the consumed coral. This allows the nudibranch to change colour (mostly between black and orange) depending on the coral system that it inhabits. However, P. melanocrachia can only feed and lay eggs on the branches of host-coral, Platygyra carnosa, which limits the geographical range and efficacy in nudibranch nutritional crypsis. Furthermore, the nudibranch colour change is not immediate, and switching between coral hosts when in search for new food or shelter can be costly.[33]

The costs associated with distractive or disruptive crypsis are more complex than the costs associated with background matching. Disruptive patterns distort the body outline, making it harder to precisely identify and locate.[34] However, disruptive patterns result in higher predation.[35] Disruptive patterns that specifically involve visible symmetry (such as in some butterflies) reduce survivability and increase predation.[36] Some researchers argue that because wing-shape and color pattern are genetically linked, it is genetically costly to develop asymmetric wing colorations that would enhance the efficacy of disruptive cryptic patterning. Symmetry does not carry a high survival cost for butterflies and moths that their predators views from above on a homogeneous background, such as the bark of a tree. On the other hand, natural selection drives species with variable backgrounds and habitats to move symmetrical patterns away from the centre of the wing and body, disrupting their predators' symmetry recognition.[37]

Principles

[edit]Camouflage can be achieved by different methods, described below. Most of the methods help to hide against a background; but mimesis and motion dazzle protect without hiding. Methods may be applied on their own or in combination. Many mechanisms are visual, but some research has explored the use of techniques against olfactory (scent) and acoustic (sound) detection.[38][39] Methods may also apply to military equipment.[40]

Background matching

[edit]Some animals' colours and patterns match a particular natural background. This is an important component of camouflage in all environments. For instance, tree-dwelling parakeets are mainly green; woodcocks of the forest floor are brown and speckled; reedbed bitterns are streaked brown and buff; in each case the animal's coloration matches the hues of its habitat.[41][42] Similarly, desert animals are almost all desert coloured in tones of sand, buff, ochre, and brownish grey, whether they are mammals like the gerbil or fennec fox, birds such as the desert lark or sandgrouse, or reptiles like the skink or horned viper.[43] Military uniforms, too, generally resemble their backgrounds; for example khaki uniforms are a muddy or dusty colour, originally chosen for service in South Asia.[44] Many moths show industrial melanism,[45] including the peppered moth which has coloration that blends in with tree bark.[46] The coloration of these insects evolved between 1860 and 1940 to match the changing colour of the tree trunks on which they rest, from pale and mottled to almost black in polluted areas.[45][c] This is taken by zoologists as evidence that camouflage is influenced by natural selection, as well as demonstrating that it changes where necessary to resemble the local background.[45]

-

Lion in Kruger National Park, South Africa, blending in with the tall grass

-

Black-faced sandgrouse is coloured like its desert background.

-

Egyptian nightjar nests in open sand with only its camouflaged plumage to protect it.

-

Bright green katydid has the colour of fresh vegetation.

Disruptive coloration

[edit]

Disruptive patterns use strongly contrasting, non-repeating markings such as spots or stripes to break up the outlines of an animal or military vehicle,[47] or to conceal telltale features, especially by masking the eyes, as in the common frog.[48] Disruptive patterns may use more than one method to defeat visual systems such as edge detection.[49] Predators like the leopard use disruptive camouflage to help them approach prey, while potential prey use it to avoid detection by predators.[50] Disruptive patterning is common in military usage, both for uniforms and for military vehicles. Disruptive patterning, however, does not always achieve crypsis on its own, as an animal or a military target may be given away by factors like shape, shine, and shadow.[51][52][53]

The presence of bold skin markings does not in itself prove that an animal relies on camouflage, as that depends on its behaviour.[54] For example, although giraffes have a high contrast pattern that could be disruptive coloration, the adults are very conspicuous when in the open. Some authors have argued that adult giraffes are cryptic, since when standing among trees and bushes they are hard to see at even a few metres' distance.[55] However, adult giraffes move about to gain the best view of an approaching predator, relying on their size and ability to defend themselves, even from lions, rather than on camouflage.[55] A different explanation is implied by young giraffes being far more vulnerable to predation than adults. More than half of all giraffe calves die within a year,[55] and giraffe mothers hide their newly born calves, which spend much of the time lying down in cover while their mothers are away feeding. The mothers return once a day to feed their calves with milk. Since the presence of a mother nearby does not affect survival, it is argued that these juvenile giraffes must be very well camouflaged; this is supported by coat markings being strongly inherited.[55]

The possibility of camouflage in plants was little studied until the late 20th century. Leaf variegation with white spots may serve as camouflage in forest understory plants, where there is a dappled background; leaf mottling is correlated with closed habitats. Disruptive camouflage would have a clear evolutionary advantage in plants: they would tend to escape from being eaten by herbivores. Another possibility is that some plants have leaves differently coloured on upper and lower surfaces or on parts such as veins and stalks to make green-camouflaged insects conspicuous, and thus benefit the plants by favouring the removal of herbivores by carnivores. These hypotheses are testable.[56][57][58]

-

Leopard: a disruptively camouflaged predator

-

Russian T-90 battle tank painted in bold disruptive pattern of sand and green

-

Gaboon viper's bold markings are powerfully disruptive.

-

A ptarmigan and five chicks exhibit exceptional disruptive camouflage

-

Jumping spider: a disruptively camouflaged invertebrate predator

-

Many understory plants such as the saw greenbriar, Smilax bona-nox have pale markings, possibly disruptive camouflage.

Eliminating shadow

[edit]

Some animals, such as the horned lizards of North America, have evolved elaborate measures to eliminate shadow. Their bodies are flattened, with the sides thinning to an edge; the animals habitually press their bodies to the ground; and their sides are fringed with white scales which effectively hide and disrupt any remaining areas of shadow there may be under the edge of the body.[59] The theory that the body shape of the horned lizards which live in open desert is adapted to minimise shadow is supported by the one species which lacks fringe scales, the roundtail horned lizard, which lives in rocky areas and resembles a rock. When this species is threatened, it makes itself look as much like a rock as possible by curving its back, emphasizing its three-dimensional shape.[59] Some species of butterflies, such as the speckled wood, Pararge aegeria, minimise their shadows when perched by closing the wings over their backs, aligning their bodies with the sun, and tilting to one side towards the sun, so that the shadow becomes a thin inconspicuous line rather than a broad patch.[60] Similarly, some ground-nesting birds, including the European nightjar, select a resting position facing the sun.[60] Eliminating shadow was identified as a principle of military camouflage during the Second World War.[61]

-

Three countershaded and cryptically coloured ibex almost invisible in the Israeli desert

-

"Shape, shine, shadow" make these 'camouflaged' military vehicles easily visible.

-

The flat-tail horned lizard's body is flattened and fringed to minimise its shadow.

-

Camouflage netting is draped away from a military vehicle to reduce its shadow.

-

A caterpillar's fringe of bristles conceals its shadow.

Distraction

[edit]Many prey animals have conspicuous high-contrast markings which paradoxically attract the predator's gaze.[d][62] These distractive markings may serve as camouflage by distracting the predator's attention from recognising the prey as a whole, for example by keeping the predator from identifying the prey's outline. Experimentally, search times for blue tits increased when artificial prey had distractive markings.[63]

Self-decoration

[edit]Some animals actively seek to hide by decorating themselves with materials such as twigs, sand, or pieces of shell from their environment, to break up their outlines, to conceal the features of their bodies, and to match their backgrounds. For example, a caddisfly larva builds a decorated case and lives almost entirely inside it; a decorator crab covers its back with seaweed, sponges, and stones.[64] The nymph of the predatory masked bug uses its hind legs and a 'tarsal fan' to decorate its body with sand or dust. There are two layers of bristles (trichomes) over the body. On these, the nymph spreads an inner layer of fine particles and an outer layer of coarser particles. The camouflage may conceal the bug from both predators and prey.[65][66]

Similar principles can be applied for military purposes, for instance when a sniper wears a ghillie suit designed to be further camouflaged by decoration with materials such as tufts of grass from the sniper's immediate environment. Such suits were used as early as 1916, the British army having adopted "coats of motley hue and stripes of paint" for snipers.[67] Cott takes the example of the larva of the blotched emerald moth, which fixes a screen of fragments of leaves to its specially hooked bristles, to argue that military camouflage uses the same method, pointing out that the "device is ... essentially the same as one widely practised during the Great War for the concealment, not of caterpillars, but of caterpillar-tractors, [gun] battery positions, observation posts and so forth."[68][69]

-

This decorator crab has covered its body with sponges.

-

Sniper in a Ghillie suit with plant materials

-

Reduvius personatus, masked hunter bug nymph, camouflaged with sand grains

-

Soviet tanks under netting dressed with vegetation, 1938

Cryptic behaviour

[edit]

Movement catches the eye of prey animals on the lookout for predators, and of predators hunting for prey.[70] Most methods of crypsis therefore also require suitable cryptic behaviour, such as lying down and keeping still to avoid being detected, or in the case of stalking predators such as the tiger, moving with extreme stealth, both slowly and quietly, watching its prey for any sign they are aware of its presence.[70] As an example of the combination of behaviours and other methods of crypsis involved, young giraffes seek cover, lie down, and keep still, often for hours until their mothers return; their skin pattern blends with the pattern of the vegetation, while the chosen cover and lying position together hide the animals' shadows.[55] The flat-tail horned lizard similarly relies on a combination of methods: it is adapted to lie flat in the open desert, relying on stillness, its cryptic coloration, and concealment of its shadow to avoid being noticed by predators.[71] In the ocean, the leafy sea dragon sways mimetically, like the seaweeds amongst which it rests, as if rippled by wind or water currents.[72] Swaying is seen also in some insects, like Macleay's spectre stick insect, Extatosoma tiaratum. The behaviour may be motion crypsis, preventing detection, or motion masquerade, promoting misclassification (as something other than prey), or a combination of the two.[73]

Motion camouflage

[edit]

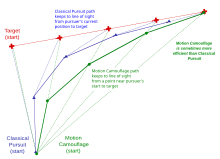

Most forms of camouflage are ineffective when the camouflaged animal or object moves, because the motion is easily seen by the observing predator, prey or enemy.[74] However, insects such as hoverflies[75] and dragonflies use motion camouflage: the hoverflies to approach possible mates, and the dragonflies to approach rivals when defending territories.[76][77] Motion camouflage is achieved by moving so as to stay on a straight line between the target and a fixed point in the landscape; the pursuer thus appears not to move, but only to loom larger in the target's field of vision.[78] Some insects sway while moving to appear to be blown back and forth by the breeze.

The same method can be used for military purposes, for example by missiles to minimise their risk of detection by an enemy.[75] However, missile engineers, and animals such as bats, use the method mainly for its efficiency rather than camouflage.[79]

-

Male Syritta pipiens hoverflies use motion camouflage to approach females

-

Male Australian Emperor dragonflies use motion camouflage to approach rivals.

-

Preying mantises exhibiting motion camouflage.

Changeable skin coloration

[edit]Animals such as chameleon, frog,[80] flatfish such as the peacock flounder, squid, octopus and even the isopod idotea balthica actively change their skin patterns and colours using special chromatophore cells to resemble their current background, or, as in most chameleons, for signalling.[81] However, Smith's dwarf chameleon does use active colour change for camouflage.[82]

Each chromatophore contains pigment of only one colour. In fish and frogs, colour change is mediated by a type of chromatophore known as melanophores that contain dark pigment. A melanophore is star-shaped; it contains many small pigmented organelles which can be dispersed throughout the cell, or aggregated near its centre. When the pigmented organelles are dispersed, the cell makes a patch of the animal's skin appear dark; when they are aggregated, most of the cell, and the animal's skin, appears light. In frogs, the change is controlled relatively slowly, mainly by hormones. In fish, the change is controlled by the brain, which sends signals directly to the chromatophores, as well as producing hormones.[83]

The skins of cephalopods such as the octopus contain complex units, each consisting of a chromatophore with surrounding muscle and nerve cells.[84] The cephalopod chromatophore has all its pigment grains in a small elastic sac, which can be stretched or allowed to relax under the control of the brain to vary its opacity. By controlling chromatophores of different colours, cephalopods can rapidly change their skin patterns and colours.[85][86]

On a longer timescale, animals like the Arctic hare, Arctic fox, stoat, and rock ptarmigan have snow camouflage, changing their coat colour (by moulting and growing new fur or feathers) from brown or grey in the summer to white in the winter; the Arctic fox is the only species in the dog family to do so.[87] However, Arctic hares which live in the far north of Canada, where summer is very short, remain white year-round.[87][88]

The principle of varying coloration either rapidly or with the changing seasons has military applications. Active camouflage could in theory make use of both dynamic colour change and counterillumination. Simple methods such as changing uniforms and repainting vehicles for winter have been in use since World War II. In 2011, BAE Systems announced their Adaptiv infrared camouflage technology. It uses about 1,000 hexagonal panels to cover the sides of a tank. The Peltier plate panels are heated and cooled to match either the vehicle's surroundings (crypsis), or an object such as a car (mimesis), when viewed in infrared.[89][90][91]

-

Rock ptarmigan, changing colour in springtime. The male is still mostly in winter plumage

-

Norwegian volunteer soldiers in Winter War, 1940, with white camouflage overalls over their uniforms

-

Arctic hares in the low arctic change from brown to white in winter

-

Snow-camouflaged German Marder III jagdpanzer and white-overalled crew and infantry in Russia, 1943

-

Veiled chameleon, Chamaeleo calyptratus, changes colour mainly in relation to mood and for signalling.

-

Adaptiv infrared camouflage lets an armoured vehicle mimic a car.

Countershading

[edit]

Countershading uses graded colour to counteract the effect of self-shadowing, creating an illusion of flatness. Self-shadowing makes an animal appear darker below than on top, grading from light to dark; countershading 'paints in' tones which are darkest on top, lightest below, making the countershaded animal nearly invisible against a suitable background.[92] Thayer observed that "Animals are painted by Nature, darkest on those parts which tend to be most lighted by the sky's light, and vice versa". Accordingly, the principle of countershading is sometimes called Thayer's Law.[93] Countershading is widely used by terrestrial animals, such as gazelles[94] and grasshoppers; marine animals, such as sharks and dolphins;[95] and birds, such as snipe and dunlin.[96][97]

Countershading is less often used for military camouflage, despite Second World War experiments that showed its effectiveness. English zoologist Hugh Cott encouraged the use of methods including countershading, but despite his authority on the subject, failed to persuade the British authorities.[98] Soldiers often wrongly viewed camouflage netting as a kind of invisibility cloak, and they had to be taught to look at camouflage practically, from an enemy observer's viewpoint.[99][100] At the same time in Australia, zoologist William John Dakin advised soldiers to copy animals' methods, using their instincts for wartime camouflage.[101]

The term countershading has a second meaning unrelated to "Thayer's Law". It is that the upper and undersides of animals such as sharks, and of some military aircraft, are different colours to match the different backgrounds when seen from above or from below. Here the camouflage consists of two surfaces, each with the simple function of providing concealment against a specific background, such as a bright water surface or the sky. The body of a shark or the fuselage of an aircraft is not gradated from light to dark to appear flat when seen from the side. The camouflage methods used are the matching of background colour and pattern, and disruption of outlines.[94]

-

Countershaded Dorcas gazelle, Gazella dorcas

-

Countershaded grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos

-

Countershaded ship and submarine in Thayer's 1902 patent application

-

Two model birds painted by Thayer: painted in background colours on the left, countershaded and nearly invisible on the right

-

Countershaded Focke-Wulf Fw 190D-9

Counter-illumination

[edit]

Counter-illumination means producing light to match a background that is brighter than an animal's body or military vehicle; it is a form of active camouflage. It is notably used by some species of squid, such as the firefly squid and the midwater squid. The latter has light-producing organs (photophores) scattered all over its underside; these create a sparkling glow that prevents the animal from appearing as a dark shape when seen from below.[102] Counterillumination camouflage is the likely function of the bioluminescence of many marine organisms, though light is also produced to attract[103] or to detect prey[104] and for signalling.

Counterillumination has rarely been used for military purposes. "Diffused lighting camouflage" was trialled by Canada's National Research Council during the Second World War. It involved projecting light on to the sides of ships to match the faint glow of the night sky, requiring awkward external platforms to support the lamps.[105] The Canadian concept was refined in the American Yehudi lights project, and trialled in aircraft including B-24 Liberators and naval Avengers.[106] The planes were fitted with forward-pointing lamps automatically adjusted to match the brightness of the night sky.[105] This enabled them to approach much closer to a target – within 3,000 yards (2,700 m) – before being seen.[106] Counterillumination was made obsolete by radar, and neither diffused lighting camouflage nor Yehudi lights entered active service.[105]

-

HMS Largs by night with incomplete diffused lighting camouflage, 1942, set to maximum brightness

-

Bulwark of HMS Largs showing 4 (of about 60) diffused lighting fittings, 2 lifted, 2 deployed

-

Yehudi Lights raise the average brightness of the plane from a dark shape to the same as the sky.

Transparency

[edit]

Many marine animals that float near the surface are highly transparent, giving them almost perfect camouflage.[107] However, transparency is difficult for bodies made of materials that have different refractive indices from seawater. Some marine animals such as jellyfish have gelatinous bodies, composed mainly of water; their thick mesogloea is acellular and highly transparent. This conveniently makes them buoyant, but it also makes them large for their muscle mass, so they cannot swim fast, making this form of camouflage a costly trade-off with mobility.[107] Gelatinous planktonic animals are between 50 and 90 percent transparent. A transparency of 50 percent is enough to make an animal invisible to a predator such as cod at a depth of 650 metres (2,130 ft); better transparency is required for invisibility in shallower water, where the light is brighter and predators can see better. For example, a cod can see prey that are 98 percent transparent in optimal lighting in shallow water. Therefore, sufficient transparency for camouflage is more easily achieved in deeper waters.[107]

Some tissues such as muscles can be made transparent, provided either they are very thin or organised as regular layers or fibrils that are small compared to the wavelength of visible light. A familiar example is the transparency of the lens of the vertebrate eye, which is made of the protein crystallin, and the vertebrate cornea which is made of the protein collagen.[107] Other structures cannot be made transparent, notably the retinas or equivalent light-absorbing structures of eyes – they must absorb light to be able to function. The camera-type eye of vertebrates and cephalopods must be completely opaque.[107] Finally, some structures are visible for a reason, such as to lure prey. For example, the nematocysts (stinging cells) of the transparent siphonophore Agalma okenii resemble small copepods.[107] Examples of transparent marine animals include a wide variety of larvae, including radiata (coelenterates), siphonophores, salps (floating tunicates), gastropod molluscs, polychaete worms, many shrimplike crustaceans, and fish; whereas the adults of most of these are opaque and pigmented, resembling the seabed or shores where they live.[107][108] Adult comb jellies and jellyfish obey the rule, often being mainly transparent. Cott suggests this follows the more general rule that animals resemble their background: in a transparent medium like seawater, that means being transparent.[108] The small Amazon River fish Microphilypnus amazonicus and the shrimps it associates with, Pseudopalaemon gouldingi, are so transparent as to be "almost invisible"; further, these species appear to select whether to be transparent or more conventionally mottled (disruptively patterned) according to the local background in the environment.[109]

Silvering

[edit]

Where transparency cannot be achieved, it can be imitated effectively by silvering to make an animal's body highly reflective. At medium depths at sea, light comes from above, so a mirror oriented vertically makes animals such as fish invisible from the side. Most fish in the upper ocean such as sardine and herring are camouflaged by silvering.[110]

The marine hatchetfish is extremely flattened laterally, leaving the body just millimetres thick, and the body is so silvery as to resemble aluminium foil. The mirrors consist of microscopic structures similar to those used to provide structural coloration: stacks of between 5 and 10 crystals of guanine spaced about 1⁄4 of a wavelength apart to interfere constructively and achieve nearly 100 per cent reflection. In the deep waters that the hatchetfish lives in, only blue light with a wavelength of 500 nanometres percolates down and needs to be reflected, so mirrors 125 nanometres apart provide good camouflage.[110]

In fish such as the herring which live in shallower water, the mirrors must reflect a mixture of wavelengths, and the fish accordingly has crystal stacks with a range of different spacings. A further complication for fish with bodies that are rounded in cross-section is that the mirrors would be ineffective if laid flat on the skin, as they would fail to reflect horizontally. The overall mirror effect is achieved with many small reflectors, all oriented vertically.[110] Silvering is found in other marine animals as well as fish. The cephalopods, including squid, octopus and cuttlefish, have multilayer mirrors made of protein rather than guanine.[110]

Ultra-blackness

[edit]

Some deep sea fishes have very black skin, reflecting under 0.5% of ambient light. This can prevent detection by predators or prey fish which use bioluminescence for illumination. Oneirodes had a particularly black skin which reflected only 0.044% of 480 nm wavelength light. The ultra-blackness is achieved with a thin but continuous layer of particles in the dermis, melanosomes. These particles both absorb most of the light, and are sized and shaped so as to scatter rather than reflect most of the rest. Modelling suggests that this camouflage should reduce the distance at which such a fish can be seen by a factor of 6 compared to a fish with a nominal 2% reflectance. Species with this adaptation are widely dispersed in various orders of the phylogenetic tree of bony fishes (Actinopterygii), implying that natural selection has driven the convergent evolution of ultra-blackness camouflage independently many times.[111]

Mimesis

[edit]In mimesis (also called masquerade), the camouflaged object looks like something else which is of no special interest to the observer.[112] Mimesis is common in prey animals, for example when a peppered moth caterpillar mimics a twig, or a grasshopper mimics a dry leaf.[113] It is also found in nest structures; some eusocial wasps, such as Leipomeles dorsata, build a nest envelope in patterns that mimic the leaves surrounding the nest.[114]

Mimesis is also employed by some predators and parasites to lure their prey. For example, a flower mantis mimics a particular kind of flower, such as an orchid.[115] This tactic has occasionally been used in warfare, for example with heavily armed Q-ships disguised as merchant ships.[116][117][118]

The common cuckoo, a brood parasite, provides examples of mimesis both in the adult and in the egg. The female lays her eggs in nests of other, smaller species of bird, one per nest. The female mimics a sparrowhawk. The resemblance is sufficient to make small birds take action to avoid the apparent predator. The female cuckoo then has time to lay her egg in their nest without being seen to do so.[119] The cuckoo's egg itself mimics the eggs of the host species, reducing its chance of being rejected.[120][121]

-

Peppered moth caterpillars mimic twigs

-

Flower mantis lures its insect prey by mimicking a Phalaenopsis orchid blossom

-

Hooded grasshopper Teratodus monticollis, superbly mimics a leaf with a bright orange border

-

This grasshopper hides from predators by mimicking a dry leaf

-

Armed WW1 Q-ship lured enemy submarines by mimicking a merchantman

-

Cuckoo adult mimics sparrowhawk, giving female time to lay eggs parasitically

-

Cuckoo eggs mimicking smaller eggs, in this case of reed warbler

-

Wrap-around spider Dolophones mimicking a stick

Motion dazzle

[edit]

Most forms of camouflage are made ineffective by movement: a deer or grasshopper may be highly cryptic when motionless, but instantly seen when it moves. But one method, motion dazzle, requires rapidly moving bold patterns of contrasting stripes.[122] Motion dazzle may degrade predators' ability to estimate the prey's speed and direction accurately, giving the prey an improved chance of escape.[123] Motion dazzle distorts speed perception and is most effective at high speeds; stripes can also distort perception of size (and so, perceived range to the target). As of 2011, motion dazzle had been proposed for military vehicles, but never applied.[122] Since motion dazzle patterns would make animals more difficult to locate accurately when moving, but easier to see when stationary, there would be an evolutionary trade-off between motion dazzle and crypsis.[123]

An animal that is commonly thought to be dazzle-patterned is the zebra. The bold stripes of the zebra have been claimed to be disruptive camouflage,[124] background-blending and countershading.[125][e] After many years in which the purpose of the coloration was disputed,[126] an experimental study by Tim Caro suggested in 2012 that the pattern reduces the attractiveness of stationary models to biting flies such as horseflies and tsetse flies.[127][128] However, a simulation study by Martin How and Johannes Zanker in 2014 suggests that when moving, the stripes may confuse observers, such as mammalian predators and biting insects, by two visual illusions: the wagon-wheel effect, where the perceived motion is inverted, and the barberpole illusion, where the perceived motion is in a wrong direction.[129]

Applications

[edit]Military

[edit]Before 1800

[edit]

Ship camouflage was occasionally used in ancient times. Philostratus (c. 172–250 AD) wrote in his Imagines that Mediterranean pirate ships could be painted blue-gray for concealment.[130] Vegetius (c. 360–400 AD) says that "Venetian blue" (sea green) was used in the Gallic Wars, when Julius Caesar sent his speculatoria navigia (reconnaissance boats) to gather intelligence along the coast of Britain; the ships were painted entirely in bluish-green wax, with sails, ropes and crew the same colour.[131] There is little evidence of military use of camouflage on land before 1800, but two unusual ceramics show men in Peru's Mochica culture from before 500 AD, hunting birds with blowpipes which are fitted with a kind of shield near the mouth, perhaps to conceal the hunters' hands and faces.[132] Another early source is a 15th-century French manuscript, The Hunting Book of Gaston Phebus, showing a horse pulling a cart which contains a hunter armed with a crossbow under a cover of branches, perhaps serving as a hide for shooting game.[133] Jamaican Maroons are said to have used plant materials as camouflage in the First Maroon War (c. 1655–1740).[134]

19th-century origins

[edit]

The development of military camouflage was driven by the increasing range and accuracy of infantry firearms in the 19th century. In particular the replacement of the inaccurate musket with weapons such as the Baker rifle made personal concealment in battle essential. Two Napoleonic War skirmishing units of the British Army, the 95th Rifle Regiment and the 60th Rifle Regiment, were the first to adopt camouflage in the form of a rifle green jacket, while the Line regiments continued to wear scarlet tunics.[135] A contemporary study in 1800 by the English artist and soldier Charles Hamilton Smith provided evidence that grey uniforms were less visible than green ones at a range of 150 yards.[136]

In the American Civil War, rifle units such as the 1st United States Sharp Shooters (in the Federal army) similarly wore green jackets while other units wore more conspicuous colours.[137] The first British Army unit to adopt khaki uniforms was the Corps of Guides at Peshawar, when Sir Harry Lumsden and his second in command, William Hodson introduced a "drab" uniform in 1848.[138] Hodson wrote that it would be more appropriate for the hot climate, and help make his troops "invisible in a land of dust".[139] Later they improvised by dyeing cloth locally. Other regiments in India soon adopted the khaki uniform, and by 1896 khaki drill uniform was used everywhere outside Europe;[140] by the Second Boer War six years later it was used throughout the British Army.[141]

During the late 19th century camouflage was applied to British coastal fortifications.[142] The fortifications around Plymouth, England were painted in the late 1880s in "irregular patches of red, brown, yellow and green."[143] From 1891 onwards British coastal artillery was permitted to be painted in suitable colours "to harmonise with the surroundings"[144] and by 1904 it was standard practice that artillery and mountings should be painted with "large irregular patches of different colours selected to suit local conditions."[145]

First World War

[edit]

In the First World War, the French army formed a camouflage corps, led by Lucien-Victor Guirand de Scévola,[146][147] employing artists known as camoufleurs to create schemes such as tree observation posts and covers for guns. Other armies soon followed them.[148][149][150] The term camouflage probably comes from camoufler, a Parisian slang term meaning to disguise, and may have been influenced by camouflet, a French term meaning smoke blown in someone's face.[151][152] The English zoologist John Graham Kerr, artist Solomon J. Solomon and the American artist Abbott Thayer led attempts to introduce scientific principles of countershading and disruptive patterning into military camouflage, with limited success.[153][154] In early 1916 the Royal Naval Air Service began to create dummy air fields to draw the attention of enemy planes to empty land. They created decoy homes and lined fake runways with flares, which were meant to help protect real towns from night raids. This strategy was not common practice and did not succeed at first, but in 1918 it caught the Germans off guard multiple times.[155]

Ship camouflage was introduced in the early 20th century as the range of naval guns increased, with ships painted grey all over.[156][157] In April 1917, when German U-boats were sinking many British ships with torpedoes, the marine artist Norman Wilkinson devised dazzle camouflage, which paradoxically made ships more visible but harder to target.[158] In Wilkinson's own words, dazzle was designed "not for low visibility, but in such a way as to break up her form and thus confuse a submarine officer as to the course on which she was heading".[159]

-

USS West Mahomet in dazzle camouflage

-

Siege howitzer camouflaged against observation from the air, 1917

-

Austro-Hungarian ski patrol in two-part snow uniforms with improvised head camouflage on Italian front, 1915–1918

Second World War

[edit]In the Second World War, the zoologist Hugh Cott, a protégé of Kerr, worked to persuade the British army to use more effective camouflage methods, including countershading, but, like Kerr and Thayer in the First World War, with limited success. For example, he painted two rail-mounted coastal guns, one in conventional style, one countershaded. In aerial photographs, the countershaded gun was essentially invisible.[160] The power of aerial observation and attack led every warring nation to camouflage targets of all types. The Soviet Union's Red Army created the comprehensive doctrine of Maskirovka for military deception, including the use of camouflage.[161] For example, during the Battle of Kursk, General Katukov, the commander of the Soviet 1st Tank Army, remarked that the enemy "did not suspect that our well-camouflaged tanks were waiting for him. As we later learned from prisoners, we had managed to move our tanks forward unnoticed". The tanks were concealed in previously prepared defensive emplacements, with only their turrets above ground level.[162] In the air, Second World War fighters were often painted in ground colours above and sky colours below, attempting two different camouflage schemes for observers above and below.[163] Bombers and night fighters were often black,[164] while maritime reconnaissance planes were usually white, to avoid appearing as dark shapes against the sky.[165] For ships, dazzle camouflage was mainly replaced with plain grey in the Second World War, though experimentation with colour schemes continued.[156]

As in the First World War, artists were pressed into service; for example, the surrealist painter Roland Penrose became a lecturer at the newly founded Camouflage Development and Training Centre at Farnham Castle,[166] writing the practical Home Guard Manual of Camouflage.[167] The film-maker Geoffrey Barkas ran the Middle East Command Camouflage Directorate during the 1941–1942 war in the Western Desert, including the successful deception of Operation Bertram. Hugh Cott was chief instructor; the artist camouflage officers, who called themselves camoufleurs, included Steven Sykes and Tony Ayrton.[168][169] In Australia, artists were also prominent in the Sydney Camouflage Group, formed under the chairmanship of Professor William John Dakin, a zoologist from Sydney University. Max Dupain, Sydney Ure Smith, and William Dobell were among the members of the group, which worked at Bankstown Airport, RAAF Base Richmond and Garden Island Dockyard.[170] In the United States, artists like John Vassos took a certificate course in military and industrial camouflage at the American School of Design with Baron Nicholas Cerkasoff, and went on to create camouflage for the Air Force.[171]

-

Maritime patrol Catalina, painted white to minimise visibility against the sky

-

USS Duluth in naval camouflage Measure 32, Design 11a, one of many dazzle schemes used on warships

-

A Spitfire's underside 'azure' paint scheme, meant to hide it against the sky

-

A Luftwaffe aircraft hangar built to resemble a street of village houses, Belgium, 1944

After 1945

[edit]Camouflage has been used to protect military equipment such as vehicles, guns, ships,[156] aircraft and buildings[172] as well as individual soldiers and their positions.[173] Vehicle camouflage methods begin with paint, which offers at best only limited effectiveness. Other methods for stationary land vehicles include covering with improvised materials such as blankets and vegetation, and erecting nets, screens and soft covers which may suitably reflect, scatter or absorb near infrared and radar waves.[174][175][176] Some military textiles and vehicle camouflage paints also reflect infrared to help provide concealment from night vision devices.[177] After the Second World War, radar made camouflage generally less effective, though coastal boats are sometimes painted like land vehicles.[156] Aircraft camouflage too came to be seen as less important because of radar, and aircraft of different air forces, such as the Royal Air Force's Lightning, were often uncamouflaged.[178]

Many camouflaged textile patterns have been developed to suit the need to match combat clothing to different kinds of terrain (such as woodland, snow, and desert).[179] The design of a pattern effective in all terrains has proved elusive.[180][181][182] The American Universal Camouflage Pattern of 2004 attempted to suit all environments, but was withdrawn after a few years of service.[183] Terrain-specific patterns have sometimes been developed but are ineffective in other terrains.[184] The problem of making a pattern that works at different ranges has been solved with multiscale designs, often with a pixellated appearance and designed digitally, that provide a fractal-like range of patch sizes so they appear disruptively coloured both at close range and at a distance.[185] The first genuinely digital camouflage pattern was the Canadian Disruptive Pattern (CADPAT), issued to the army in 2002, soon followed by the American Marine pattern (MARPAT). A pixellated appearance is not essential for this effect, though it is simpler to design and to print.[186]

-

British Disruptive Pattern Material, issued to special forces in 1963 and universally by 1968

-

2007 2-colour snow variant of Finnish Defence Forces M05 pattern

-

Modern German Flecktarn 1990, developed from a 1938 pattern, a non-digital pattern which works at different distances

-

US "Chocolate Chip" Six-Color Desert Pattern developed in 1962, widely used in Gulf War

Hunting

[edit]

Hunters of game have long made use of camouflage in the form of materials such as animal skins, mud, foliage, and green or brown clothing to enable them to approach wary game animals.[187] Field sports such as driven grouse shooting conceal hunters in hides (also called blinds or shooting butts).[188] Modern hunting clothing makes use of fabrics that provide a disruptive camouflage pattern; for example, in 1986 the hunter Bill Jordan created cryptic clothing for hunters, printed with images of specific kinds of vegetation such as grass and branches.[189]

Civil structures

[edit]

Camouflage is occasionally used to make built structures less conspicuous: for example, in South Africa, towers carrying cell telephone antennae are sometimes camouflaged as tall trees with plastic branches, in response to "resistance from the community". Since this method is costly (a figure of three times the normal cost is mentioned), alternative forms of camouflage can include using neutral colours or familiar shapes such as cylinders and flagpoles. Conspicuousness can also be reduced by siting masts near, or on, other structures.[190]

Automotive manufacturers often use patterns to disguise upcoming products. This camouflage is designed to obfuscate the vehicle's visual lines, and is used along with padding, covers, and decals. The patterns' purpose is to prevent visual observation (and to a lesser degree photography), that would subsequently enable reproduction of the vehicle's form factors.[191]

Fashion, art and society

[edit]

Military camouflage patterns influenced fashion and art from the time of the First World War onwards. Gertrude Stein recalled the cubist artist Pablo Picasso's reaction in around 1915:

I very well remember at the beginning of the war being with Picasso on the boulevard Raspail when the first camouflaged truck passed. It was at night, we had heard of camouflage but we had not seen it and Picasso amazed looked at it and then cried out, yes it is we who made it, that is cubism.

— Gertrude Stein in From Picasso (1938)[192]

In 1919, the attendants of a "dazzle ball", hosted by the Chelsea Arts Club, wore dazzle-patterned black and white clothing. The ball influenced fashion and art via postcards and magazine articles.[193] The Illustrated London News announced:[193][194]

The scheme of decoration for the great fancy dress ball given by the Chelsea Arts Club at the Albert Hall, the other day, was based on the principles of "Dazzle", the method of "camouflage" used during the war in the painting of ships ... The total effect was brilliant and fantastic.

More recently, fashion designers have often used camouflage fabric for its striking designs, its "patterned disorder" and its symbolism.[195] Camouflage clothing can be worn largely for its symbolic significance rather than for fashion, as when, during the late 1960s and early 1970s in the United States, anti-war protestors often ironically wore military clothing during demonstrations against the American involvement in the Vietnam War.[196]

Modern artists such as Ian Hamilton Finlay have used camouflage to reflect on war. His 1973 screenprint of a tank camouflaged in a leaf pattern, Arcadia,[f] is described by the Tate as drawing "an ironic parallel between this idea of a natural paradise and the camouflage patterns on a tank".[197] The title refers to the Utopian Arcadia of poetry and art, and the memento mori Latin phrase Et in Arcadia ego which recurs in Hamilton Finlay's work. In science fiction, Camouflage is a novel about shapeshifting alien beings by Joe Haldeman.[198] The word is used more figuratively in works of literature such as Thaisa Frank's collection of stories of love and loss, A Brief History of Camouflage.[199]

In 1986, Andy Warhol began a series of monumental camouflage paintings, which helped to transform camouflage into a popular print pattern. A year later, in 1987, New York designer Stephen Sprouse used Warhol's camouflage prints as the basis for his Autumn Winter 1987 collection.[200]

-

André Mare's Cubist sketch, c. 1917, of a 280 calibre gun illustrates the interplay of art and war, as artists like Mare contributed their skills as wartime camoufleurs.

-

Camouflage clothing in an anti-war protest, 1971

-

A camouflage skirt as a fashion item, 2007

Notes

[edit]- ^ A letter from Alfred Russel Wallace to Darwin of 8 March 1868 mentioned such colour change: "Would you like to see the specimens of pupæ of butterflies whose colours have changed in accordance with the colour of the surrounding objects? They are very curious, and Mr. T. W. Wood, who bred them, would, I am sure, be delighted to bring them to show you."[5]

- ^ Cott explains Beddard's observation as a coincident disruptive pattern.[9]

- ^ Before 1860, unpolluted tree trunks were often covered in pale lichens; polluted trunks were bare, and often nearly black.

- ^ These distraction markings are sometimes called dazzle markings, but have nothing to do with motion dazzle or wartime dazzle painting.

- ^ The belly of the zebra is white, and the dark stripes narrow towards the belly, so the animal is certainly countershaded, but this does not prove that the main function of the stripes is camouflage.

- ^ See Ian Hamilton Finlay#Art.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Aristotle (c. 350 BC). Historia Animalium. IX, 622a: 2–10. Cited in Borrelli, Luciana; Gherardi, Francesca; Fiorito, Graziano (2006). A catalogue of body patterning in Cephalopoda. Firenze University Press. ISBN 978-88-8453-377-7. Abstract Archived 6 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Darwin 1859.

- ^ a b Darwin 1859, p. 84.

- ^ Poulton 1890, p. 111.

- ^ Wallace, Alfred Russel (8 March 1868). "Alfred Russel Wallace Letters and Reminiscences By James Marchant". Darwin Online. Retrieved 29 March 2013.

- ^ Poulton 1890, p. Fold-out after p. 339.

- ^ Beddard 1892, p. 83.

- ^ Beddard 1892, p. 87.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Beddard 1892, p. 122.

- ^ Thayer 1909.

- ^ Forbes 2009, p. 77.

- ^ Thayer 1909, pp. 5, 16.

- ^ Rothenberg 2011, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Wright, Patrick (23 June 2005). "Cubist Slugs. Review of DPM: Disruptive Pattern Material; An Encyclopedia of Camouflage: Nature – Military – Culture by Roy Behrens". London Review of Books. 27 (12): 16–20.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 47–67.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 174–186.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 153–155.

- ^ Troscianko, Jolyon; Wilson-Aggarwal, Jared; Stevens, Martin; Spottiswoode, Claire N. (29 January 2016). "Camouflage predicts survival in ground-nesting birds". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 19966. Bibcode:2016NatSR...619966T. doi:10.1038/srep19966. PMC 4731810. PMID 26822039.

- ^ Sabeti, P. C.; Schaffner, S. F.; Fry, B.; et al. (16 June 2006). "Positive Natural Selection in the Human Lineage". Science. 312 (5780): 1614–1620. Bibcode:2006Sci...312.1614S. doi:10.1126/science.1124309. PMID 16778047. S2CID 10809290.

- ^ Lindgren, Johan; Sjövall, Peter; Carney, Ryan M.; et al. (February 2014). "Skin pigmentation provides evidence of convergent melanism in extinct marine reptiles". Nature. 506 (7489): 484–488. Bibcode:2014Natur.506..484L. doi:10.1038/nature12899. PMID 24402224. S2CID 4468035.

- ^ Pavid, Katie (28 June 2016). "Oldest insect camouflage behaviour revealed by fossils".

- ^ Watson, Traci (14 September 2016). "This Dinosaur Wore Camouflage". National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 6 November 2019.

- ^ Song, Weiwei; Li, Ronghua; Zhao, Yun; et al. (15 February 2021). "Pharaoh Cuttlefish, Sepia pharaonis, Genome Reveals Unique Reflectin Camouflage Gene Set". Frontiers in Marine Science. 8: 639670. doi:10.3389/fmars.2021.639670. hdl:1893/32292. ISSN 2296-7745.

- ^ Guan, Zhe; Cai, Tiantian; Liu, Zhongmin; Dou, Yunfeng; Hu, Xuesong; Zhang, Peng; Sun, Xin; Li, Hongwei; Kuang, Yao; Zhai, Qiran; Ruan, Hao (September 2017). "Origin of the Reflectin Gene and Hierarchical Assembly of Its Protein". Current Biology. 27 (18): 2833–2842.e6. Bibcode:2017CBio...27E2833G. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.07.061. PMID 28889973. S2CID 9974056.

- ^ van't Hof, Arjen E.; Campagne, Pascal; Rigden, Daniel J.; Yung, Carl J.; Lingley, Jessica; Quail, Michael A.; Hall, Neil; Darby, Alistair C.; Saccheri, Ilik J. (June 2016). "The industrial melanism mutation in British peppered moths is a transposable element". Nature. 534 (7605): 102–105. Bibcode:2016Natur.534..102H. doi:10.1038/nature17951. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 27251284. S2CID 3989607.

- ^ Werneck, Jane Margaret Costa de Frontin; Torres, Lucas; Provance, David Willian; Brugnera, Ricardo; Grazia, Jocelia (3 December 2021). "First Report of Predation by a Stink Bug on a Walking-Stick Insect with Reflections on Evolutionary Mechanisms for Camouflage". doi:10.21203/rs.2.10812/v1. S2CID 240967012.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Voisey, Joanne; Van Daal, Angela (February 2002). "Agouti: from Mouse to Man, from Skin to Fat". Pigment Cell Research. 15 (1): 10–18. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0749.2002.00039.x. PMID 11837451.

- ^ Pfeifer, Susanne P; Laurent, Stefan; Sousa, Vitor C.; et al. (15 January 2018). "The Evolutionary History of Nebraska Deer Mice: Local Adaptation in the Face of Strong Gene Flow". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 35 (4): 792–806. doi:10.1093/molbev/msy004. ISSN 0737-4038. PMC 5905656. PMID 29346646.

- ^ Eizirik, Eduardo; Yuhki, Naoya; Johnson, Warren E.; et al. (March 2003). "Molecular Genetics and Evolution of Melanism in the Cat Family". Current Biology. 13 (5): 448–453. Bibcode:2003CBio...13..448E. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00128-3. PMID 12620197. S2CID 19021807.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Allen, William L.; Sherratt, Thomas N.; Speed, Michael P. (2018). Background matching. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199688678.003.0002. ISBN 978-0-19-968867-8.

- ^ Wong, Kwan Ting; Ng, Tsz Yan; Tsang, Ryan Ho Leung; Ang, Put (24 June 2017). "First observation of the nudibranch Tenellia feeding on the scleractinian coral Pavona decussata". Coral Reefs. 36 (4): 1121. Bibcode:2017CorRe..36.1121W. doi:10.1007/s00338-017-1603-8. S2CID 33882835.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Allen, William L.; Sherratt, Thomas N.; Speed, Michael P. (20 September 2018). Disruptive camouflage. Vol. 1. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780199688678.003.0003. ISBN 978-0-19-968867-8.

- ^ Stevens, Martin; Marshall, Kate L. A.; Troscianko, Jolyon; et al. (2013). "Revealed by Conspicuousness: Distractive Markings Reduce Camouflage". Behavioral Ecology. 24 (1): 213–222. doi:10.1093/beheco/ars156. ISSN 1465-7279.

- ^ Cuthill, Innes C.; Hiby, Elly; Lloyd, Emily (22 May 2006). "The Predation Costs of Symmetrical Cryptic Coloration". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 273 (1591): 1267–1271. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3438. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1560277. PMID 16720401.

- ^ Wainwright, J. Benito; Scott-Samuel, Nicholas E.; Cuthill, Innes C. (15 January 2020). "Overcoming the Detectability Costs of Symmetrical Coloration". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 287 (1918): 20192664. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2664. PMC 7003465. PMID 31937221.

- ^ Conner, William E. (2014). "Adaptive Sounds and Silences: Acoustic Anti-Predator Strategies in Insects". Insect Hearing and Acoustic Communication. Animal Signals and Communication. Vol. 1. pp. 65–79. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-40462-7_5. ISBN 978-3-642-40461-0. ISSN 2197-7305.

adaptive silence, acoustic crypsis, stealth,

- ^ Miller, Ashadee Kay; Maritz, Bryan; McKay, Shannon; Glaudas, Xavier; Alexander, Graham J. (22 December 2015). "An ambusher's arsenal: chemical crypsis in the puff adder (Bitis arietans)". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 282 (1821). The Royal Society: 20152182. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2182. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 4707760. PMID 26674950.

Field observations of puff adders (Bitis arietans) going undetected by several scent-orientated predator and prey species led us to investigate chemical crypsis in this ambushing species. We trained dogs (Canis familiaris) and meerkats (Suricata suricatta) to test whether a canid and a herpestid predator could detect B. arietans using olfaction.

- ^ Costa, James T. (2007). "How a naturalist found safe colours for soldiers". Nature. 448 (7152): 408. Bibcode:2007Natur.448..408C. doi:10.1038/448408c. ISSN 0028-0836.

cryptic coloration in British field uniforms was not fully adopted until the Boer War

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 5–19.

- ^ Forbes 2009, p. 51.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Newark 2007, pp. 45–46.

- ^ a b c Cott 1940, p. 17.

- ^ Still, J. (1996). Collins Wild Guide: Butterflies and Moths. HarperCollins. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-00-220010-3.

- ^ Barbosa, A.; Mathger, L. M.; Buresch, K. C.; Kelly, J.; Chubb, C.; Chiao, C.; Hanlon R. T. (2008). "Cuttlefish camouflage: The effects of substrate contrast and size in evoking uniform, mottle or disruptive body patterns". Vision Research. 48 (10): 1242–1253. doi:10.1016/j.visres.2008.02.011. PMID 18395241. S2CID 16287514.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 83–91.

- ^ Osorio, Daniel; Cuthill, Innes C. "Camouflage and perceptual organization in the animal kingdom" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 25 October 2013.

- ^ Stevens, Martin; Cuthill, Innes C.; Windsor, A. M. M.; Walker, H. J. (7 October 2006). "Disruptive contrast in animal camouflage". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 273 (1600): 2433–2436. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3614. PMC 1634902. PMID 16959632.

- ^ Sweet, K. M. (2006). Transportation and Cargo Security: Threats and Solutions. Prentice Hall. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-13-170356-8.

- ^ FM 5–20: Camouflage, Basic Principles. U.S. War Department. November 2015 [1944].

- ^ Field Manual Headquarters No. 20-3 − Camouflage, Concealment, and Decoys (PDF). Department of the Army. 30 August 1999. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 November 2021.

- ^ Roosevelt, Theodore (1911). "Revealing and concealing coloration in birds and mammals". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 30 (Article 8): 119–231. hdl:2246/470. Roosevelt attacks Thayer on page 191, arguing that neither zebra nor giraffe are "'adequately obliterated' by countershading or coloration pattern or anything else."

- ^ a b c d e Mitchell, G.; Skinner, J. D. (2003). "On the origin, evolution and phylogeny of giraffes Giraffa camelopardalis" (PDF). Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa. 58 (1): 51–73. Bibcode:2003TRSSA..58...51M. doi:10.1080/00359190309519935. S2CID 6522531. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 September 2015. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- ^ Lev-Yadun, Simcha (2003). "Why do some thorny plants resemble green zebras?". Journal of Theoretical Biology. 224 (4): 483–489. Bibcode:2003JThBi.224..483L. doi:10.1016/s0022-5193(03)00196-6. PMID 12957121.

- ^ Lev-Yadun, Simcha (2006). Teixeira da Silva, J.A. (ed.). Defensive coloration in plants: a review of current ideas about anti-herbivore coloration strategies. Global Science Books. pp. 292–299. ISBN 978-4903313092.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Givnish, T. J. (1990). "Leaf Mottling: Relation to Growth Form and Leaf Phenology and Possible Role as Camouflage". Functional Ecology. 4 (4): 463–474. Bibcode:1990FuEco...4..463G. doi:10.2307/2389314. JSTOR 2389314.

- ^ a b Sherbrooke, W. C. (2003). Introduction to horned lizards of North America. University of California Press. pp. 117–118. ISBN 978-0-520-22825-2.

- ^ a b Cott 1940, pp. 104–105.

- ^ U.S. War Department (November 1943). "Principles of Camouflage". Tactical and Technical Trends (37).

- ^ Stevens, Martin; Merilaita, S. (2009). "Defining disruptive coloration and distinguishing its functions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1516): 481–488. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0216. PMC 2674077. PMID 18990673.

- ^ Dimitrova, M.; Stobbe, N.; Schaefer, H. M.; Merilaita, S. (2009). "Concealed by conspicuousness: distractive prey markings and backgrounds". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 276 (1663): 1905–1910. doi:10.1098/rspb.2009.0052. PMC 2674505. PMID 19324754.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 50–51 and passim.

- ^ Wierauch, C. (2006). "Anatomy of disguise: camouflaging structures in nymphs of Some Reduviidae (Heteroptera)" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3542): 1–18. doi:10.1206/0003-0082(2006)3542[1:AODCSI]2.0.CO;2. hdl:2246/5820. S2CID 7894145. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 August 2017.

- ^ Bates, Mary (10 June 2015). "Natural Bling: 6 Amazing Animals That Decorate Themselves". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Cott 1940, p. 360.

- ^ Ruxton, Graeme D.; Stevens, Martin (1 June 2015). "The evolutionary ecology of decorating behaviour". Biology Letters. 11 (6): 20150325. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0325. PMC 4528480. PMID 26041868.

- ^ a b Cott 1940, p. 141.

- ^ "What is a Horned Lizard?". hornedlizards.org. Horned Lizard Conservation Society. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Leafy Sea Dragon". WWF. Retrieved 21 December 2011.

- ^ Bian, Xue; Elgar, Mark A.; Peters, Richard A. (2016). "The swaying behavior of Extatosoma tiaratum: motion camouflage in a stick insect?". Behavioral Ecology. 27 (1): 83–92. doi:10.1093/beheco/arv125.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 141–143.

- ^ a b Srinivasan, M. V.; Davey, M. (1995). "Strategies for active camouflage of motion". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 259 (1354): 19–25. Bibcode:1995RSPSB.259...19S. doi:10.1098/rspb.1995.0004. S2CID 131341953.

- ^ Hopkin, Michael (5 June 2003). "Dragonfly flight tricks the eye". Nature. doi:10.1038/news030602-10. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ^ Mizutani, A. K.; Chahl, J. S.; Srinivasan, M. V. (5 June 2003). "Insect behaviour: Motion camouflage in dragonflies". Nature. 65 (423): 604. Bibcode:2003Natur.423..604M. doi:10.1038/423604a. PMID 12789327. S2CID 52871328.

- ^ Glendinning, P (2004). "The mathematics of motion camouflage". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 271 (1538): 477–481. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2622. PMC 1691618. PMID 15129957.

- ^ Ghose, K.; Horiuchi, T. K.; Krishnaprasad, P. S.; Moss, C. F. (2006). "Echolocating Bats Use a Nearly Time-Optimal Strategy to Intercept Prey". PLOS Biology. 4 (5): e108. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0040108. PMC 1436025. PMID 16605303.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 52, 236.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, Devi; Moussalli, Adnan; Whiting, Martin J. (23 August 2008). "Predator-specific camouflage in chameleons". Biology Letters. 4 (4): 326–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0173. PMC 2610148. PMID 18492645.

- ^ Wallin, M. (2002). "Nature's Palette" (PDF). Bioscience Explained. 1 (2): 1–12. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 17 November 2011.

- ^ Cott 1940, p. 32.

- ^ Cloney, R. A.; Florey, E. (1968). "Ultrastructure of Cephalopod Chromatophore Organs". Zeitschrift für Zellforschung und Mikroskopische Anatomie. 89 (2): 250–280. doi:10.1007/BF00347297. PMID 5700268. S2CID 26566732.

- ^ "Day Octopuses, Octopus cyanea". MarineBio Conservation Society. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Arctic Wildlife". Churchill Polar Bears. 2011. Retrieved 22 December 2011.

- ^ Hearn, Brian (20 February 2012). The Status of Arctic Hare (Lepus arcticus bangsii) in Insular Newfoundland (PDF). Newfoundland Labrador Department of Environment and Conservation. p. 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ "Tanks test infrared invisibility cloak". BBC News. 5 September 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- ^ "Adaptiv – A Cloak of Invisibility". BAE Systems. 2011. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "Innovation Adaptiv Car Signature". BAE Systems. 2012. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ Cott 1940, pp. 35–46.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 72–73.

- ^ a b Kiltie, Richard A. (January 1998). "Countershading: Universally deceptive or deceptively universal?". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 3 (1): 21–23. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(88)90079-1. PMID 21227055.

- ^ Cott 1940, p. 41.

- ^ Ehrlich, Paul R.; Dobkin, David S.; Wheye, Darryl (1988). "The Color of Birds". Stanford University. Retrieved 1 February 2013.

- ^ Cott 1940, p. 40.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 146–150.

- ^ Forbes 2009, p. 152.

- ^ Barkas 1952, p. 36.

- ^ Elias 2011, pp. 57–66.

- ^ "Midwater Squid, Abralia veranyi". Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Young, Richard Edward (October 1983). "Oceanic Bioluminescence: an Overview of General Functions". Bulletin of Marine Science. 33 (4): 829–845.

- ^ Douglas, R. H.; Mullineaux, C. W.; Partridge, J. C. (September 2000). "Long-wave sensitivity in deep-sea stomiid dragonfish with far-red bioluminescence: evidence for a dietary origin of the chlorophyll-derived retinal photosensitizer of Malacosteus niger". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 355 (1401): 1269–1272. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0681. PMC 1692851. PMID 11079412.

- ^ a b Hambling, David (9 May 2008). "Cloak of Light Makes Drone Invisible?". Wired. Retrieved 17 June 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g Herring 2002, pp. 190–191.

- ^ a b Cott 1940, p. 6.

- ^ Carvalho, Lucélia Nobre; Zuanon, Jansen; Sazima, Ivan (April–June 2006). "The almost invisible league: crypsis and association between minute fishes and shrimps as a possible defence against visually hunting predators". Neotropical Ichthyology. 4 (2): 219–224. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252006000200008.

- ^ a b c d Herring 2002, pp. 192–195.

- ^ Davis, Alexander L.; Thomas, Kate N.; Goetz, Freya E.; et al. (2020). "Ultra-black Camouflage in Deep-Sea Fishes". Current Biology. 30 (17): 3470–3476.e3. Bibcode:2020CBio...30E3470D. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.044. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 32679102.

- ^ Gullan, P. J.; Cranston, P. S. (2010). The Insects (4th ed.). John Wiley, Blackwell. pp. 512–513. ISBN 978-1-4443-3036-6.

- ^ Forbes 2009, p. 151.

- ^ Ross, Kenneth G. (1991). The Social Biology of Wasps. Cornell Press. p. 233. ISBN 978-0-801-49906-7.

- ^ Forbes 2009, p. 134.

- ^ Beyer, Kenneth M. (1999). Q-Ships versus U-Boats: America's Secret Project. Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-55750-044-1.

- ^ McMullen, Chris (2001). "Royal Navy 'Q' Ships". Great War Primary Documents Archive. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ^ Forbes 2009, pp. 6–42.

- ^ Welbergen, J; Davies, N. B. (2011). "A parasite in wolf's clothing: hawk mimicry reduces mobbing of cuckoos by hosts". Behavioral Ecology. 22 (3): 574–579. doi:10.1093/beheco/arr008.

- ^ Brennand, Emma (24 March 2011). "Cuckoo in egg pattern 'arms race'". BBC News. Retrieved 22 August 2011.

- ^ Moskát, C; Honza, M. (2002). "European Cuckoo Cuculus canorus parasitism and host's rejection behaviour in a heavily parasitized Great Reed Warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus population". Ibis. 144 (4): 614–622. doi:10.1046/j.1474-919X.2002.00085.x.

- ^ a b Scott-Samuel, N. E.; Baddeley, R.; Palmer, C. E.; Cuthill, Innes C. (June 2011). Burr, David C. (ed.). "Dazzle Camouflage Affects Speed Perception". PLOS ONE. 6 (6): e20233. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...620233S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0020233. PMC 3105982. PMID 21673797.

- ^ a b Stevens, Martin; Searle, W. T. L.; Seymour, J. E.; Marshall, K. L. A.; Ruxton, Graeme D. (25 November 2011). "Motion dazzle and camouflage as distinct anti-predator defenses". BMC Biology. 9: 9–81. doi:10.1186/1741-7007-9-81. PMC 3257203. PMID 22117898.

- ^ Cott 1940, p. 94.

- ^ Thayer 1909, p. 136.

- ^ Caro, Tim (2009). "Contrasting coloration in terrestrial mammals". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B. 364 (1516): 537–548. doi:10.1098/rstb.2008.0221. PMC 2674080. PMID 18990666.

- ^ Waage, J. K. (1981). "How the zebra got its stripes: biting flies as selective agents in the evolution of zebra colouration". J. Entom. Soc. South Africa. 44: 351–358.

- ^ Egri, Ádám; Blahó, Miklós; Kriska, György; et al. (March 2012). "Polarotactic tabanids find striped patterns with brightness and/or polarization modulation least attractive: an advantage of zebra stripes". The Journal of Experimental Biology. 215 (5): 736–745. doi:10.1242/jeb.065540. PMID 22323196.

- ^ How, Martin J.; Zanker, Johannes M. (2014). "Motion camouflage induced by zebra stripes" (PDF). Zoology. 117 (3): 163–170. Bibcode:2014Zool..117..163H. doi:10.1016/j.zool.2013.10.004. PMID 24368147.

- ^ Casson 1995, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Casson 1995, p. 235.

- ^ Jett, Stephen C. (March 1991). "Further Information on the Geography of the Blowgun and Its Implications for Early Transoceanic Contacts". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 81 (1): 89–102. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1991.tb01681.x. JSTOR 2563673.

- ^ Payne-Gallwey, Ralph (1903). The Crossbow. Longmans, Green. p. 11.

- ^ Saunders, Nicholas (2005). The People of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archaeology and Traditional Culture. ABC-CLIO.

- ^ Haythornthwaite, P. (2002). British Rifleman 1797–1815. Osprey Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 978-1841761770.

- ^ Newark 2007, p. 43.

- ^ "Killers in Green Coats". Weider History Group. 20 February 2008. Retrieved 8 July 2012.

- ^ "Khaki Uniform 1848–49: First Introduction by Lumsden and Hodson". Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research. 82 (Winter): 341–347. 2004.

- ^ Hodson, W. S. R. (1859). Hodson, George H. (ed.). Twelve Years of a Soldier's Life in India, being extracts from the letters of the late Major WSR Hodson. John W. Parker and Son.