Morecambe and Wise

| Morecambe and Wise | |

|---|---|

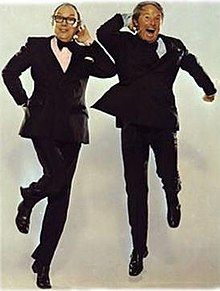

Morecambe (left) and Wise in their "skip dance" pose, performed to the song "Bring Me Sunshine" | |

| Born |

|

| Died |

|

| Medium | Film, television, stand-up, music, books |

| Years active | 1941–1984 |

| Genres | Observational comedy, musical comedy, satire |

| Subject(s) | Marriage, everyday life, current events, pop culture |

Eric Morecambe (John Eric Bartholomew; 14 May 1926 – 28 May 1984) and Ernie Wise (Ernest Wiseman; 27 November 1925 – 21 March 1999), known as Morecambe and Wise (and sometimes as Eric and Ernie), were an English comic double act, working in variety, radio, film and most successfully in television. Their partnership lasted from 1941 until Morecambe's sudden death in 1984. They have been described as "the most illustrious, and the best-loved, double-act that Britain has ever produced".[1]

On a list of the 100 Greatest British Television Programmes drawn up by the British Film Institute in 2000, voted for by industry professionals, The Morecambe and Wise Show was placed 14th. In September 2006, they were voted by the general public as number 2 in a poll of TV's 50 Greatest Stars. Their early career was the subject of the 2011 television biopic Eric and Ernie, and their 1970s career was the subject of the television biopic Eric, Ernie and Me in 2017.

In 1976, Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise were both awarded the OBE. In 1999, they were posthumously awarded the BAFTA Fellowship. In 2013, they were honoured with a blue plaque at Teddington Studios, where their last four series of The Morecambe and Wise Show were recorded.[2]

History

[edit]Morecambe and Wise's friendship began in 1940 when they were each booked separately to appear in Jack Hylton's revue Youth Takes a Bow at the Nottingham Empire Theatre. At the suggestion of Eric's mother, Sadie, they worked on a double act. They made their double act debut, as Bartholomew and Wise,[3] in August 1941 at the Liverpool Empire. War service broke up the act but they reunited by chance at the Swansea Empire Theatre in 1946 when they joined forces again. In 1950 Wise wrote to Bartholomew (Morecambe) saying that he wanted to break up the act as he thought it would not work. Morecambe responded that he had never heard such rubbish in his life, and advised Wise to get some rest before they got back to finding work.[4]

They made their name in variety, appearing in a variety circus, the Windmill Theatre, the Glasgow Empire and many venues around Britain.[5] After this they made their name in radio, first in Variety Fanfare (Ronnie Taylor, Hulme Hippodrome) made by the BBC in Manchester, and then with their own radio show, You're Only Young Once, first broadcast on 9 November 1953.[6] With national fame they transferred to television in 1954. Their debut TV show, Running Wild, was not well received and led to a damning newspaper review: "Definition of the week: TV set – the box in which they buried Morecambe and Wise." Eric apparently carried a copy of this review around with him ever afterward, and from then on the duo kept a tight control over their material. In 1956 they were offered a spot in the Winifred Atwell show with material written by Johnny Speight and this was a success. In 1959 they topped the bill in BBC TV's long-running variety show The Good Old Days in a Boxing Day edition of the programme. In later years the pair became a Christmas TV institution in their own right.

They had a series of shows that spanned over twenty years, during which time they developed and honed their act, most notably after moving to the BBC in 1968, where they were to be teamed with their long-term writer Eddie Braben. It is this period of their careers that is widely regarded as their "glory days". Their shows were:

- Running Wild (BBC, 1954) (Various writers)

- Two of a Kind (ATV, 1961–68) (Writers: Hills and Green)

- The Morecambe & Wise Show (BBC, 1968–77) (Writers: Hills and Green (1968), Eddie Braben (1969–77))

- The Morecambe & Wise Show (Thames Television, 1978–83) (writers: Barry Cryer and John Junkin (1978), Eddie Braben (1980–83))

- The Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise Show (BBC Radio 2, 1975–78. Writer: Eddie Braben)

The pair starred in three feature films during the 1960s – The Intelligence Men (1965), That Riviera Touch (1966), and The Magnificent Two (1967). In 1983 they made their last film, Night Train to Murder. They were also guests on many television variety series; however, it was in a US series that they appeared as guests most frequently, featuring twelve times on The Ed Sullivan Show between 1963 and 1968 – more than any other British entertainers. The duo were featured in a comic book in 1977.[7]

As well as their TV work, the duo made two radio series. The first,"The Morecambe and Wise Show", was broadcast in 1966, and included plays and musical numbers as well as the stand-up routine with which they always opened their show. Some of the plays would be adapted for TV. In the early 1970s the pair made a second radio series, but due to the BBC refusing the use of "The Morecambe and Wise Show" name, the series was titled "The Eric Morecambe and Ernie Wise Radio Show".

Style and performance

[edit]Morecambe and Wise started as a song-and-dance comedic team, with Morecambe playing the more bumbling comic role and Wise the affable straight man, but over time (and with new writers) the nature of the act changed. By the 1960s, the characters were more complex, with both Morecambe and Wise playing comedic characters who could set up each other for laughs, as well as garner big laughs with their many catchphrases, character bits and reactions. In essence, the straight man/wacky comic dynamic shifted, so that both men were equally capable of fulfilling either role. In the later and most successful part of their career, which spanned the 1970s, Morecambe and Wise were joined behind the scenes by Eddie Braben, a script writer who generated almost all their material (Morecambe and Wise were also sometimes credited as supplying "additional material") and defined what is now thought of as typical Morecambe and Wise humour. Together Morecambe, Wise and Braben were known as "The Golden Triangle", becoming one of the UK's all-time favourite comedy acts.

John Ammonds was also central to the duo's most successful period in the 1970s. As the producer of the BBC TV shows, it was his idea to involve celebrity guests. He also perfected the duo's familiar dance, which was based on a dance performed by Groucho Marx in the film Horse Feathers.[8]

Ernest Maxin started choreographing the musical numbers in 1970, and succeeded John Ammonds as producer of the BBC TV shows in 1974. Maxin, who won a BAFTA for the Best Light Entertainment Show for the Morecambe and Wise 1977 Christmas Show, was also responsible for devising and choreographing many of their great musical comedy routines including "The Breakfast Sketch", "Singin' in the Rain", and the homage to South Pacific, "There is Nothing Like a Dame" featuring BBC newsreaders in an acrobatic dance routine.

Catchphrases and visual gags

[edit]Much of the material of the Morecambe and Wise shows consisted of their well-worn catch phrases that recurred like motifs throughout their career. Barely a show would go by without Eric referring to Ernie's "short, fat, hairy legs",[9] or pointing out that "you can't see the join", where Ernie's supposed wig was attached. The wig sometimes appeared in the credits, with variations on "Mr Wise appears by kind permission of Rentawig". Eric never seemed to tire of offering his partner some "Tea, Ern?", a pun on "tea urn", a vessel for serving hot drinks used in workplaces. If anyone fluffed their line, Eric would usually say, "That's easy for you to say!" or "You can say that again". When Ernie disagreed with him, Eric would say, "Just watch it, that's all!"; often said by Eric when grabbing Ernie by the lapels.[9] If someone said a line whilst he was looking at somebody else, Eric would say, "You said that without moving your lips"; as if the non-speaker were a ventriloquist throwing his or her voice. Another ventriloquial allusion (probably quoting Arthur Worsley) was made when Eric said, should his intended listener be looking away, "Look at me when I'm talking to you!"

Some catch phrases developed from earlier sketches. When Eric played an incompetent 'Mr Memory', unable to remember anything without unsubtle prompting from Ernie, Ernie prompted Eric with "Arsenal!" disguised very badly as a cough. Later, whenever Ernie, or anyone else, coughed or sneezed, Eric would shout "Arsenal!"[10]

The catchphrase "Hello folks, and what about the workers?" was developed by Eric from a similar saying by Harry Secombe in The Goon Show.[9] For Secombe this was a simple greeting, while for Eric it expressed his great sexual interest in some pretty girl or female guest. It was often accompanied by him slapping the back of his own neck to recover his concentration.

Their treatment of their guest stars was terrible for effect. Eric and sometimes Ernie would often call an invited guest by the wrong name. So André Previn was "Andrew Preview", Ian Carmichael was Hoagy Carmichael, Elton John was Elephant John, Vanessa Redgrave was "Vanilla Redgrave" and when The Beatles appeared, Ringo Starr was "Bongo". Alternatively, one or both would seem not to recognise the famous guest artist at all. The pair would frequently make fun of their old friend, the singer and entertainer Des O'Connor in various disparaging ways.[11] A rhyming example was: "If you want me to be a goner, get me an LP by Des O'Connor". Another typical example was "There's only one thing wrong with Des O'Connor records. The hole in the middle isn't big enough". O'Connor actually appeared in the 1975 Christmas special and eavesdropped on these insults before Eric and Ernie noticed him. In reality some of these put-downs were suggested by Des himself.

Many of their catch phrases entered the language. Particularly when they were at their peak, people could be heard using them for humorous effect. The question: "What do you think of it so far?", said by Eric, who would use a prop—such as a statue or stuffed toy—to answer: "Rubbish!", was frequently heard.[9] Morecambe said later that whenever Luton Town were playing away and he happened to be in the director's box, if Luton were behind at half-time the home fans would shout, "What do you think of it so far?" Other examples were: "There's no answer to that!", which was said by Eric after anything which could be construed as innuendo.[12] He would also say "Pardon?" for a similar effect.

Schoolboys could be seen holding an open hand underneath a friend's chin while saying, "Get out of that without moving!" When Eric did this to Ernie, it was meant to be a karate move that incapacitated the victim. It was often followed by "You can't, can you?" Also common was, "They can't touch you for it" (i.e., it is not illegal); a comment following a slightly obscure word, turning it into a double entendre. In addition, Eric would say "Be honest" directly to the audience if they had carried out what he thought was a particularly successful routine. If Ernie received a little applause for something, Eric would say "I see your fan's in", and whenever the doorbell rang in their shared flat, Eric would say to Ernie, "How do you do that?"

Another long-running - usually incomplete - gag was when Eric begins a story, ‘There were two old men sitting in deckchairs. One turns to the other and says, “It’s nice out today"'. Ernie usually closed down the gag at that point as it was obviously heading for a rude punchline. Occasionally, however, he would close it with "Well, put it away, there's a Policeman coming!" In a Christmas special when the duo were being interviewed by Sir David Frost, Eric concluded the story with "You're right, I think I'll get mine out."

During the shows in which Ernie's execrable plays were shown, a catch phrase for Ernie was developed. This was, "The play what I wrote", which also was used commonly elsewhere.[13] Guest stars were conned into taking part in these plays and made to utter such grammatical monstrosities as when Glenda Jackson (at the time a noted Shakespearean actress) had to say, "All men are fools and what makes them so is having beauty, like what I have got", to the obvious smug satisfaction of the words' supposed author.[14]

Several visual gags were often repeated.

Very frequently used, and copied by the public, was Eric slapping the shoulders and then both sides of Ernie's face. A particular affectation of Eric was him putting his glasses askew or waggling them up and down on his nose. As with André Previn, if they appeared uncooperative, Eric would grab a guest by the lapels and pull them to his face in a threatening manner. He would also grimace like Humphrey Bogart (or so he thought) if Ernie or a guest was particularly challenging.

Eric would often hold an empty paper bag in one hand, throw an imaginary coin, or other small object, into the air, watch it during its flight and then flick the bag with his finger giving the impression that the item had landed in the bag. Again, he would hold a paper cup in his mouth and over his nose to perform a brief impersonation of Jimmy Durante, singing, 'Sitting at my pianna the udder day...'

Ernie would appear on a curtained stage expecting Eric to join him from behind the curtain, but Eric would be unable to find the opening and have to fight his way on. This gag could be reversed with Eric trying to fight his way off, often asking Ernie if he had a key to unlock the curtain. Another curtain gag would have Eric standing in front of the stage curtains or at the side of the stage and pretending that an arm (his own) comes out from behind the curtain and seizes him by the throat. If Eric had his back to a guest, he would jerk his body as if the guest had goosed him. This was seemingly adlibbed by Eric during a scene in the play "Robin Hood": it would appear that Ann Hamilton (as Maid Marion) was unable to exit the stage as she was supposed to owing to Eric standing on her flowing dress.

Often, Eric would suddenly notice the camera and put on a fixed, cheesy grin. Ernie would frequently notice him doing this, stand behind Eric and grin a similar grin into the camera, over Eric's shoulder. Eric and Ernie would introduce the special guest facing stage-left with their arms out. However, the guest would enter from stage-right. Also, at the end of several shows, the duo would exit the stage by skipping while putting alternate hands behind their heads and backs.

Television series

[edit]Typical Morecambe and Wise programmes were effectively sketch shows crossed with a sitcom. The duo would usually open the show as themselves on a mock stage in front of curtains emblazoned with an M and W logo. Morecambe and Wise's comic style varied subtly throughout their career, depending on their writers. Their writers during most of the 1960s, Dick Hills and Sid Green, took a relatively straightforward approach, depicting Eric as an aggressive, knockabout comedian and Ernie as an essentially conventional and somewhat disapproving straight man. When Eddie Braben took over as writer, he made the relationship considerably deeper and more complex. The critic Kenneth Tynan noted that, with Braben as writer, Morecambe and Wise had a unique dynamic—Ernie was a comedian who wasn't funny, while Eric was a straight man who was funny.[15] The Ernie persona became simultaneously more egotistical and more naïve. Morecambe pointed out that Braben wrote him as "tougher, less gormless, harder towards Ern."[16] Wise's contribution to the humour is a subject of an ongoing debate. To the end of his life he would always reject interviewers' suggestions that he was the straight man, preferring to call himself the song-and-dance man. However, Wise's skill and dedication was essential to their joint success, and Tynan praised Wise's performance as "unselfish, ebullient and indispensable".[17]

A central concept was that the duo lived together as close, long-term friends (there were many references to a childhood friendship) who shared not merely a flat but also a bed—although their relationship was purely platonic and merely continued a tradition of comic partners sleeping in the same bed that had begun with Laurel and Hardy. Morecambe was initially uncomfortable with the bed-sharing sketches, but changed his mind upon being reminded of the Laurel and Hardy precedent; however, he still insisted on smoking his pipe in the bed scenes "for the masculinity". The front room of the flat and also the bedroom were used frequently throughout the show episodes, although Braben would also transplant the duo into various external situations, such as a health food shop or a bank. Many references were made to Ernie's supposed meanness with money and drink (for example Eric telling Shirley Bassey of Ernie's dislike of her hit "Big Spender").

Another concept of the shows during the Braben era was Ernie's utterly confident presentation of amateurishly inept plays "wot I wrote". This allowed for another kind of sketch: the staged historical drama, which usually parodied genuine historical television plays or films (such as Stalag 17, Antony and Cleopatra, or Napoleon and Josephine). Wise's character would write a play, complete with cheap props, shaky scenery and appallingly clumsy writing ("the play what I wrote" became a catchphrase), which would then be acted out by Morecambe, Wise and the show's guest star. Guests who participated included many big names of the 1970s and 1980s, such as Dame Flora Robson, Penelope Keith, Laurence Olivier, Sir John Mills, Vanessa Redgrave, Eric Porter, Peter Cushing (who, in a running gag, would keep turning up to complain that he had not been paid for an earlier appearance) and Frank Finlay, as well as Glenda Jackson (as Cleopatra: "All men are fools. And what makes them so is having beauty like what I have got..."). Jackson had not previously been known as a comedian, and this appearance led to her Oscar-winning role in A Touch of Class. Morecambe and Wise would often pretend not to have heard of their guest, or would appear to confuse them with someone else (former UK Prime Minister Harold Wilson returned the favour, when appearing as a guest at the duo's flat, by referring to Morecambe as "Mor-e-cam-by"). Also noteworthy was the occasion when the respected BBC newsreader Angela Rippon was induced to show her legs in a dance number (she had trained as a ballet dancer before she became a journalist and TV presenter). Braben later said that a large amount of the duo's humour was based on irreverence. A running gag in a number of shows was a short sequence showing a well-known artist in close-up saying "I appeared in an Ernie Wise play, and look what happened to me!". The camera would then pull back and show the artist doing some low-status job such as newspaper seller (Ian Carmichael), Underground guard (Fenella Fielding), dustman (Eric Porter), bus conductor (André Previn), or some other ill-paid employment. However, celebrities felt they had received the highest accolade in showbusiness by being invited to appear in "an Ernest Wide play" as Ernie once mispronounced it during a show's introduction involving "Vanilla" (Vanessa) Redgrave.

As a carry-over from their music hall days, Eric and Ernie sang and danced at the end of each show, although they were forced to abandon this practice when Morecambe's heart condition prevented him from dancing. The solution was that Eric would walk across the stage with coat and bag, ostensibly to wait for his bus, while Ernie danced by himself. Their peculiar skipping dance, devised by their BBC producer John Ammonds, was a modified form of a dance used by Groucho Marx. Their signature tune was "Bring Me Sunshine". They either sang this at the end of each show or it was used as a theme tune during the credits (although in their BBC shows they used other songs as well, notably "Following You Around", "Positive Thinking" "Don't You Agree" and "Just Around the Corner"). A standard gag at the end of each show was for Janet Webb to appear behind the pair, walk to the front of the stage and push them out of her way. She would then recite:

I'd like to thank you for watching me and my little show here tonight. If you've enjoyed it then it's all been worthwhile. So until we meet again, goodnight, and I love you all!

Webb was never announced, and seldom appeared in their shows in any other role. According to a BBC documentary, this was a parody of George Formby's wife, who used to come on stage to take the bows with him at the end of a show.[citation needed]

Another running gag involved an old colleague from their music hall days, harmonica player Arthur Tolcher. Arthur would keep appearing on the stage in evening wear and would play the opening bars of "España cañí" on his harmonica, only to be told "Not now, Arthur!" At the very end of the show, following the final credit, Arthur would sneak on stage and begin to play, only for the screen to cut to black.

In June 2007, the BBC released a DVD of surviving material from their first series in 1968, and the complete second series from 1969. In November 2011, Network DVD released the complete, uncut 13 episodes of the second ATV series of Two of a Kind from 1962. It was advertised as the first series due to the fact the original first series is completely missing from television archives.

In 2020, a black and white copy of an episode from October 1970, believed lost, was found in the attic of Morecambe's widow. It was restored for re-broadcast at Christmas 2021.[18]

Christmas specials

[edit]With the exception of 1974, the show had end-of-year Christmas specials, which became some of the highest-rated TV programmes of the era. Braben has said that people judged the quality of their Christmas experience on the quality of the Morecambe and Wise Christmas Special. From 1969 until 1980, except 1974, the shows were always broadcast on Christmas Day. Due to Eric Morecambe's heart attack, Christmas Day 1974 featured a highlights package of clips from previous shows rather than a new programme, introduced by Michael Parkinson, including a newly recorded interview with Morecambe & Wise.[19]

The Morecambe and Wise Christmas Show on BBC in 1977 scored one of the highest ever audiences in British television history with more than 20 million viewers (the cited figure varies between 21 and 28 million, depending on the source).[20][21][22][23][24][25][26] The duo remain among the most consistently high-rating performers of all time on British television, regularly topping the in-week charts during their heyday in the 1970s and early 1980s.

Famous sketches

[edit]- Grieg's Piano Concerto

Classic sketches from such shows often revolve around the guest stars. One example is the 1971 appearance of André Previn, who is introduced onstage by Ernie as Andrew Preview. Previn's schedule was extremely tight, and Morecambe and Wise were worried that he had very little time to rehearse: popular myth holds that Previn had to learn his lines in the taxi on the way from the airport, but in reality he had taken part in two days of rehearsals (out of a planned five) before having to fly to America to see his mother, who had been taken ill. The final result was described by their biographer as "probably their finest moment".[27]

The sketch was a rework of one which appeared in Two of a Kind (Series 3, Episode 7)[28] and written by Green and Hills.

Previn is initially enthusiastic as a guest, but he is perplexed by the news that he will not, after all, be conducting Yehudi Menuhin in Mendelssohn's Violin Concerto, but Edvard Grieg's A minor Piano Concerto with Eric as piano soloist:

Ernie: I can assure you that Eric is more than capable.

Previn: Well—all right. I'll go and get my baton.

Ernie: Please do that.

Previn: It's in Chicago.[29]

At this point in the sketch Morecambe punches the air with his fist and ad-libs the line "Pow! He's in! I like him! I like him!".[30] The television executive Michael Grade has observed that it was Previn's expert delivery of his lines that caused Morecambe to visibly relax: "Eric's face lights up as if to say, 'Oh, yes! This is going to be great!"[30] Since Previn had little time to rehearse, his comic timing was a surprise to Morecambe, who had explained to Previn simply that "None of the three of us should believe that this is funny."[31]

Eric goes on to treat Previn and the orchestra with his customary disdain ("In the Second Movement, not too heavy on the banjos") and produces his own score ("autographed copies available afterwards, boys") but consistently fails to enter on the conductor's cue. This is because, when the orchestra begins, Eric is standing right next to Previn. During the introductory bars, Eric has to descend from the conductor's rostrum, down to his place at the piano. This he cannot do in the time available—or rather, deliberately meanders so as to miss his cue. After failing twice to reach the piano, they decide he should be seated there at the start.[32] Even then, he cannot see Previn when the conductor gestures for him to begin playing, because the piano lid obscures his view. Previn has to leap in the air at the appropriate time, so that Eric can see him. When he finally manages to enter on time, Eric's rendition of the piano part is so bizarre that Previn becomes exasperated and tells Eric that he is playing "all the wrong notes". Eric stands up, seizes Previn by the lapels and menacingly informs him "I'm playing all the right notes—but not necessarily in the right order."[32] Previn demonstrates how the piece should be played but Eric, after a moment's reflection, delivers a verdict of "Rubbish!" and he and Ernie walk off in disgust. Previn starts playing Eric's version and the duo rush back, declare that Previn has finally "got it" and start dancing ecstatically.[32] The sketch's impact can be assessed by the fact that twenty-five years later, London taxi drivers were still addressing André Previn as "Mr. Preview".[33]

- Singin' in the Rain

One of the famous Morecambe and Wise routines is their 1976 Christmas Show parody of the scene from the film Singin' in the Rain in which Gene Kelly dances in the rain and sings the song "Singin' in the Rain". This recreation features Ernie exactly copying Gene Kelly's dance routine, on a set which exactly copies the set used in the movie. Eric performs the role of the policeman. The difference from the original is that in the Morecambe and Wise version, there is no water, except for some downpours onto Eric's head (through a drain, or dumped out of a window, etc.). This lack of water was initially because of practical considerations (the floor of the studio had many electrical cables on it, and such quantities of water would be dangerous)—but Morecambe and Wise found a way to turn the lack of water into a comic asset. The sketch was devised and choreographed by Ernest Maxin.

- The Breakfast Sketch

This 1976 sketch has become one of the duo's most familiar, and is a parody of a stripper routine where Eric and Ernie are seen listening to the radio at breakfast time. This sketch was not an original but was adapted from an earlier one Benny Hill performed on his own show during the mid-1960s. David Rose's tune "The Stripper" comes on and the duo perform a dance using various kitchen utensils and food items, including Ernie catching slices of toast as they pop out of the toaster, and finally opening the fridge door to be bathed in light, as if on stage, while they pull out strings of sausages which they whirl around to the music. The sketch was choreographed and produced by Ernest Maxin.

In December 2007, viewers of satellite channel Gold voted the sketch the best moment of Morecambe and Wise's shows.[34]

Propellerheads parodied the sketch in the video for their 1998 single "Crash!"[35] and it was parodied in two UK television commercials in 2008, for PG Tips and Aunt Bessie's Yorkshire Puddings.

Bring Me Sunshine

[edit]Bring Me Sunshine was a gala concert held at the London Palladium on 28 November 1984 in the presence of Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh in aid of the British Heart Foundation and was held in memory of Morecambe who had died the previous May after many years of heart problems. It was hosted by Wise and featured a host of personalities all paying their tribute to Morecambe. The show began with a dance routine, the theme for the whole evening's music being "sunshine" the dancers were accompanied by "You Are the Sunshine of My Life", which was followed by the big entrance of Wise who first spoke, and then sang the duo's signature tune. This was an emotive moment for Wise, and one that showed how big a part Morecambe had played in his life. Other stars that appeared over the course of the evening were:

- Benny Hill (who performed his headmaster routine, complete with lectern)

- Dickie Henderson (with his well-known "off-key singer" routine)

- Cannon & Ball (who had been cited as the next big double act)

- Kenny Ball & His Jazzmen (who had appeared on many of their shows)

- Angela Rippon (who recreated her tiller girl dance routine)

- James Casey, Eli Woods & Roy Castle (elephant in the box routine)

- Bruce Forsyth (who played piano and did a stand-up routine)

- Des O'Connor (the long-term butt of Morecambe's jibes)

There was also a sequence in which the guests of honour were announced and appeared on stage, these included the following guest stars, fans and celebrities:

The programme was filmed live and televised on ITV on Christmas Day of that year; in his summing up Des O'Connor gave a touching and heartfelt tribute to Morecambe proclaiming that "...on the way here tonight I went through Trafalgar Square and the Christmas decorations were going up. I looked at the giant tree and thought to myself 'there's going to be one less star on the tree this year.' " It was a glittering night that featured the cream of British talent paying tribute to a man who had been considered the best of the best among his peers.

The programme, made and broadcast by Thames Television was aired once and has never been repeated or made commercially available in any format. However, the segment of Bruce Forsyth's piano playing and dancing was used in a compilation programme, Heroes Of Comedy, made in 1994 for Channel 4.

Tribute album

[edit]Eric and Ernie often cited the earlier comedy team Flanagan and Allen as influences on their own work; although Morecambe and Wise never imitated or copied Flanagan and Allen, they did sometimes work explicit references to the earlier team into their own cross-talk routines and sketches. In 1971 they recorded a tribute album, Morecambe and Wise Sing Flanagan and Allen (Philips 6382 095), in which they performed some of the earlier team's more popular songs in their own style, without attempting to imitate the originals.

Films

[edit]- The Intelligence Men (1965)

- That Riviera Touch (1966)

- The Magnificent Two (1967)

- Night Train to Murder (TV film, 1985)

Personal lives

[edit]Eric Morecambe married Joan Bartlett in 1952; six weeks later, Ernie Wise married dancer Doreen Blythe, whom he had met in 1947. The Morecambes raised three children, but Wise resolved never to have a family; in Doreen's words, "Ernie always said that as soon as children are involved the wife stays home, and that's where trouble lies."[36]

Morecambe had periods of poor health, and smoked and drank heavily. He suffered a heart attack in 1968, followed by another after bypass surgery in 1979; these compelled him to stop smoking and drinking, and he became a celebrity spokesman for heart research. His fatal heart attack, in 1984, struck during a curtain call of a performance in Tewkesbury, Gloucestershire.[37]

After Morecambe's death, Wise fell back on his song-and-dance skills and pursued a solo career, with limited success. He ultimately gave up performing and found new success as an elder statesman of British comedy, giving interviews, telling anecdotes, and appearing at awards ceremonies.[38] Wise maintained a vacation home in Florida, where he suffered two heart attacks in November 1998. After triple bypass surgery, Wise returned to England and convalesced for five months at Nuffield Hospital in Berkshire, where he died peacefully.[39]

Notes

[edit]- ^ McCann 1999, p. 4

- ^ "Morecambe and Wise blue plaque unveiled at Teddington Studios". BBC. 19 May 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2013.

- ^ Brown, Mark (18 November 2024). "Wise told Morecambe he wanted to split up comedy act in 1950, letter reveals". The Guardian.

- ^ "Eric and Ernie letter unearthed". BBC NEWS. 12 October 2009.

- ^ These were all referred to in the drama "Eric and Ernie", broadcast 1 January 2011.

- ^ Barfe, Louis (2021). Sunshine and Laughter: the story of Morecambe and Wise. Apollo books. pp. 51–55.

- ^ "The Morecambe & Wise Comic Book (review)". MorecambeandWise.com. 2008.

- ^ McCann 1999, p. 224

- ^ a b c d Partridge, Eric (1986). A dictionary of catch phrases: British and American, from the sixteenth century to the present day. Routledge.

- ^ Tynan, Kenneth (1976). The sound of two hands clapping. Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. p. 71. ISBN 9780030167263.

- ^ Sellers & Hogg.

- ^ Fergusson, R. (1994). Shorter dictionary of catch phrases. Routledge.

- ^ Cunliffe, A. L. (2009). A Very Short, Fairly Interesting and Reasonably Cheap Book about Management. Sage Publications. p. 63. ISBN 9781412935470.

- ^ Sellers & Hogg,Ch. 25.

- ^ Tynan 2007, p. 231

- ^ Tynan 2007, p. 230

- ^ Tynan 2007, p. 225

- ^ "Morecambe and Wise: Rediscovered episode to air on BBC Two". BBC News. 23 December 2021.

- ^ "BBC Programme Index". genome.ch.bbc.co.uk.

- ^ The Guinness Book of Records.

- ^ "Eric and Ern – The Morecambe & Wise Show: Series 8". Morecambeandwise.com. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ "Ernie Wise". The Daily Telegraph. 22 March 1999. Archived from the original on 25 March 2010. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Barfe, Louis (22 November 2008). "How John Sergeant revived did-you-see TV". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ Bushby, Helen (30 December 2010). "Victoria Wood tells all about Eric and Ernie". BBC News. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ ITV and the BFI quote a figure of 21.3 million. "Features | Britain's Most Watched TV | 1970s". BFI. 4 September 2006. Archived from the original on 22 November 2005. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- ^ Moran, Joe (22 March 2011). "One nation Christmas television". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 August 2011.

- ^ McCann 1999, pp. 235, 246

- ^ "Morecambe & Wise Episode Guides".

- ^ McCann 1999, pp. 233–234

- ^ a b McCann 1999, p. 247

- ^ McCann, Graham (13 December 2020). "The Prelude of Mr Preview: How André Previn won over Morecambe & Wise". British Comedy Guide. Retrieved 5 February 2022.

- ^ a b c McCann 1999, p. 234

- ^ McCann 1999, p. 268

- ^ "UKTV Gold: Entertainment: Morecambe and Wise: The Greatest Moment". Uktv.co.uk. Retrieved 3 January 2009.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "Propellerheads – Crash!". YouTube. Retrieved 18 June 2013.

- ^ Doreen Wise to Bridie Pearson-Jones, The Daily Mail, Apr. 20, 2018.

- ^ The New York Times, "Eric Morecambe, 58, Is Dead; A British Comic and TV Star," May 29, 1984.

- ^ Stephen Dixon, The Guardian, Mar. 22, 1999.

- ^ Stuart Millar, The Guardian, "Ernie Wise, the straighten who was no stooge, dies at 73," Mar. 22, 1999.

References

[edit]- McCann, Graham (1999). Morecambe & Wise. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 1-85702-911-9.

- Sellars, Robert; Hogg, James (2011). Little Ern: The authorised biography of Ernie Wise. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 9780283071577.

- Tynan, Kenneth (2007). Profiles. London: Nick Hern Books. ISBN 978-1-85459-943-8.

External links

[edit]- Morecambe and Wise discography at Discogs

- Morecambe and Wise at IMDb

- Morecambe & Wise Eric And Ern - Keeping the Magic Alive (books, film, TV reviews, interviews)

- Morecambe & Wise biography, plus complete list of radio/television/film/book/record appearances at Laughterlog.com

- Morecambe & Wise in advert for Texaco with racing driver James Hunt, at YouTube

- Morecambe & Wise in advert for the Atari 2600 computer games console, at YouTube