Withnail and I

| Withnail and I | |

|---|---|

Original UK release poster Art by Ralph Steadman | |

| Directed by | Bruce Robinson |

| Written by | Bruce Robinson |

| Produced by | Paul Heller |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Peter Hannan |

| Edited by | Alan Strachan |

| Music by | |

| Distributed by | HandMade Films |

Release date |

|

Running time | 107 minutes[2] |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Budget | £1.1 million[1][a] |

| Box office | $2 million[3] |

Withnail and I is a 1987 British black comedy film written and directed by Bruce Robinson. Loosely based on Robinson's life in London in the late 1960s, the plot follows two unemployed actors, Withnail and "I" (portrayed by Richard E. Grant and Paul McGann, respectively) who share a flat in Camden Town in 1969. Needing a holiday, they obtain the key to a country cottage in the Lake District belonging to Withnail's eccentric uncle Monty and drive there. The weekend holiday proves less recuperative than they expected.

Withnail and I was Grant's film debut and established his profile. Featuring performances by Richard Griffiths as Withnail's Uncle Monty and Ralph Brown as Danny the drug dealer, the film has tragic and comic elements and is notable for its period music and many quotable lines. It has been described as "one of Britain's biggest cult films".[4]

The character "I" is named "Marwood" in the published screenplay but goes unnamed in the film credits.[5]

Plot

[edit]In September 1969, two unemployed young actors, flamboyant alcoholic Withnail and contemplative Marwood, live in a messy flat in Camden Town, London. Their only regular visitor is their drug dealer, Danny. One morning, the pair squabble about housekeeping and then leave for a stroll. In Regent's Park, they discuss the poor state of their acting careers and the desire for a holiday; Marwood proposes a trip to a rural cottage near Penrith owned by Withnail's wealthy uncle Monty. They visit Monty that evening at his luxurious Chelsea house. Monty is a melodramatic aesthete, who Marwood infers is homosexual. The three briefly drink together as Withnail casually lies to Monty about his acting career. He further deceives Monty by implying that Marwood attended Eton College ("the other place"), whilst a lithograph of Harrow School seen earlier in the flat suggests that both Monty and Withnail were educated there. Withnail persuades his uncle to lend them the cottage key and they leave.

Withnail and Marwood drive to the cottage the next day but find the weather cold and wet, the cottage without provisions and the locals unwelcoming—in particular a poacher, Jake, whom Withnail offends in the pub. Marwood becomes anxious when he later sees Jake prowling around the cottage and suggests they leave for London the next day. Withnail in turn demands that they share a bed in the interest of safety but Marwood refuses. During the night, Withnail fears that the poacher wants to harm them and climbs under the covers with Marwood, who angrily leaves for a different bed. Hearing the sounds of an intruder breaking into the cottage, Withnail again joins Marwood in bed. The intruder turns out to be Monty, with supplies.

The next day, Marwood realises Monty's visit has ulterior motives when he makes aggressive sexual advances upon him; Withnail seems oblivious to this. Monty drives them into town and gives them money to buy wellington boots but they go to a pub instead, and then to a small cafe where they cause a disturbance. Monty is hurt, though he forgets the offence as the three drink and play poker. Marwood is terrified by the thought of Monty's further sexual overtures and wants to leave immediately, but Withnail insists on staying. Late in the night, Marwood tries to avoid Monty's company but is eventually cornered in the guest bedroom as Monty demands sex. Monty also reveals that Withnail, during the visit in London, lied that Marwood was a closet homosexual. Marwood lies that Withnail is the closeted one and that the two of them are in a committed relationship, which Withnail wishes to keep secret from his family and that this is the first night in six years that they have not slept together. Monty, a romantic, believes this explanation and leaves after apologising for coming between them. In private, Marwood furiously confronts Withnail.

The next morning, they find Monty has left for London, leaving a note wishing them happiness together. They continue to argue. A telegram arrives from Marwood's agent with a possible offer of work and he insists they return. As Marwood sleeps in the car, Withnail drunkenly speeds most of the way back until pulled over by the police who arrest him for driving under the influence. The pair return to the flat to find Danny and a friend named Presuming Ed squatting. Marwood calls his agent and discovers he is wanted for the lead part in a play but will need to move to Manchester to take it. The four share a huge cannabis joint but the celebration ends when Marwood learns they have received an eviction notice for unpaid rent, while Withnail is too high to care. Marwood—with new haircut—packs a bag to leave for the railway station. He turns down Withnail's offer of a goodbye drink, so Withnail walks with him to the station. In Regent's Park, Marwood reciprocates Withnail saying that he will miss him, and then leaves. Alone with bottle of wine in hand, Withnail performs "What a piece of work is a man!" from Hamlet to the wolves in a nearby Zoo enclosure, and then turns to walk home in the rain.

Cast

[edit]- Richard E. Grant as Withnail

- Paul McGann as "...& I" (Marwood)

- Richard Griffiths as Monty (Montague H. Withnail)

- Ralph Brown as Danny

- Michael Elphick as Jake

- Daragh O'Malley as Irishman (aggressive pub visitor)

- Michael Wardle as Isaac Parkin (farmer)

- Una Brandon-Jones as Mrs Parkin

- Noel Johnson as General (bar owner)

- Irene Sutcliffe as Waitress

- Llewellyn Rees as Tea Shop Proprietor

- Robert Oates as Policeman 1

- Anthony Wise as Policeman 2

- Eddie Tagoe as Presuming Ed

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Writing

[edit]The film is an adaptation of an unpublished novel written by Robinson in 1969–1970 (an early draft of which sold at auction for £8,125 in 2015).[6][7] Actor friend Don Hawkins passed a copy of the manuscript to his friend Mordecai (Mody) Schreiber in 1980.[citation needed] Schreiber paid Robinson £20,000 to adapt it into a screenplay,[citation needed] which Robinson did in the early 1980s.[citation needed] When meeting Schreiber in Los Angeles, Robinson expressed concern that he might not be able to continue because the writing broke basic screenplay rules and was hard to make work as a film.[citation needed] It used colloquial English to which few Americans would connect ("Give me a tanner and I'll give him a bell."); characters in dismal circumstances and a plot prodded by uncinematic voice-overs. Schreiber told him that that was precisely what he wanted.[citation needed] On completing the script, producer Paul Heller urged Robinson to direct it and found funding for half the film.[citation needed] The script was then passed to HandMade Films and George Harrison agreed to fund the remainder of the film.[8] Robinson's script is largely autobiographical. "Marwood" is Robinson; "Withnail" is based on Vivian MacKerrell, a friend with whom he shared a Camden house and "Uncle Monty" is loosely based on Franco Zeffirelli, from whom Robinson received unwanted amorous attentions when he was a young actor.[9] He lived in the impoverished conditions seen in the film and wore plastic bags as Wellington boots.[citation needed] For the script, Robinson condensed two or three years of his life into two or three weeks.[10] Robinson stated he named the character of Withnail after a childhood acquaintance named Jonathan Withnall, who was "the coolest guy I had ever met in my life".[11]

Early in the film, Withnail reads a newspaper headline "Boy lands plum role for top Italian director" and suggests that the director is sexually abusing the boy. This is a reference to the sexual harassment that Robinson alleges he suffered at the hands of Zeffirelli when, at age 21, he won the role of Benvolio in Romeo and Juliet.[12] Robinson attributed Uncle Monty's question to Marwood ("Are you a sponge or a stone?") as a direct quote from Zeffirelli.[13][14] The headline "Nude au pair's secret life" was an actual headline from News of the World on 16 November 1969.[15]

The end of the novel saw Withnail dying by suicide by pouring a bottle of wine into the barrel of Monty's shotgun and then pulling the trigger as he drank from it. Robinson changed the ending, as he believed it was "too dark".[16]

Name of "I"

[edit]

While the name of "I" is never spoken in the film, in the screenplay it is "Marwood". The name "Marwood" is used by Robinson in interviews and in writing as well as by Grant and McGann in the 1999 Channel 4 documentary short Withnail and Us.[13][17][18][19] The name "Marwood" was known to film critic Vincent Canby of the New York Times in a 27 March 1987 review coinciding with the film's New York premiere at the New Directors/New Films series at the Museum of Modern Art.[20] In the end credits and most media relating to the film, McGann's character is referred to solely as "...& I". In the supplemental material packaged with the Special Edition DVD in the UK, McGann's character is referred to as Peter Marwood in the cast credits.[citation needed]

It has been suggested that it is possible that 'Marwood' can be heard near the beginning of the film: As the characters escape from the Irishman in the Mother Black Cap, Withnail shouts "Out of my way <indistinct word>!". Some hear this line as "Out of the way, Marwood!", although the script reads simply "Get out of my way!".

Although the first name of "I" is not stated anywhere in the film, it is widely believed[by whom?] that it is "Peter". This myth arose as a result of a line of misheard dialogue.[21] In the scene where Monty meets the two actors, Withnail asks him if he would like a drink. In his reply, Monty both accepts his offer and says "...you must tell me all the news, I haven't seen you since you finished your last film". While pouring another drink, and downing his own, Withnail replies that he has been "Rather busy uncle. TV and stuff". Then pointing at Marwood he says "He's just had an audition for rep". Some hear this line as "Peter's had an audition for rep", although the original shooting script and all commercially published versions of the script read "he's".

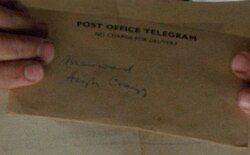

Towards the end of the film, a telegram arrives at Crow Crag on which the name "Marwood" is partially visible.

Pre-production

[edit]Peter Frampton worked as make-up artist, Sue Love as hair stylist and Andrea Galer as costume designer.[22]

Casting

[edit]Mary Selway worked as casting director.[22]

McGann was Robinson's first choice for "I" but he was fired during rehearsals because Robinson decided McGann's Scouse (Liverpool) accent was wrong for the character. Several other actors read for the role but McGann eventually persuaded Robinson to re-audition him, promising to affect a Home Counties accent and quickly won back the part.[23]

Actors Robinson considered for "Withnail" included Daniel Day-Lewis,[24][25] Bill Nighy,[24][25] Kenneth Branagh[24] and Edward Tudor-Pole.[25] Robinson claims that Grant was too fat to play Withnail and told him that "half of you has got to go".[24] Grant has denied this.[26]

Though he plays a raging alcoholic, Grant is a teetotaller with an allergy to alcohol. He had never been drunk prior to making the film. Robinson decided that it would be impossible for Grant to play the character without having ever experienced inebriation and a hangover, so he "forced" the actor on a drinking binge. Grant has stated that he was "violently sick" after each drink and found the experience deeply unpleasant.[27]

Filming

[edit]

According to Grant's book, With Nails, filming commenced on 2 August 1986 in the Lake District and shooting took seven weeks. A rough cut was screened to the actors in a Wardour Street screening room on 8 December 1986.[28] Denis O'Brien, who oversaw the filming on behalf of HandMade Films, nearly shut the film down on the first day of production. He thought that the film had no "discernible jokes" and was badly lit.[24] During the filming of the scene in which Withnail drinks a can of lighter fluid, Robinson changed the contents of the can between takes from water to vinegar to get a better reaction from Grant.[29] The film cost £1.1 million to make.[1][a] Robinson received £80,000 to direct, £30,000 of which he reinvested into the film to shoot additional scenes such as the journeys to and from Penrith, which HandMade Films would not fund. The money was never reimbursed after the film's success.[30] Ringo Starr is credited as a "Special Production Consultant" under his legal name, Richard Starkey MBE.[22]

Cumbria

[edit]The film was shot almost entirely on location. There was no filming in the real Penrith; the locations used were in and around nearby Shap and Bampton, Cumbria. Monty's cottage, Crow Crag, is Sleddale Hall, near the Wet Sleddale Reservoir just outside Shap, although the lake that Crow Crag apparently overlooks is Haweswater Reservoir. The bridge where Withnail and Marwood go fishing with a shotgun is over the River Lowther. The telephone box in which Withnail calls his agent is beside Wideworth Farm Road in Bampton.[31]

Sleddale Hall was offered for sale in January 2009 with a starting price of £145,000.[32] Sebastian Hindley, who owns the Mardale Inn in Bampton, won the auction at a price of £265,000 but he failed to secure financing and the property was resold for an undisclosed sum to Tim Ellis, an architect from Kent, whose original bid failed at the auction.[33]

Hertfordshire

[edit]Exterior and ground floor interior shots of Crow Crag were shot at Sleddale Hall in Cumbria and Stockers Farm in Rickmansworth, Hertfordshire, and the bedroom and stair scenes of Crow Crag were also filmed in Hertfordshire. Stockers Farm was also the location for the Crow and Crown pub.[34]

Buckinghamshire

[edit]

The King Henry pub and the Penrith Tea Rooms scenes were filmed in the Market Square in Stony Stratford, Milton Keynes, Buckinghamshire, at what is now The Crown Inn Stony Stratford and Cox & Robinson pharmacy, respectively.[35]

London

[edit]Withnail and Marwood's flat was located at 57 Chepstow Place in Bayswater, W2. The shot of them leaving for Penrith as they turn left from the building being demolished was shot on Freston Road, W11.[34] The Mother Black Cap pub was played by the Frog and Firkin pub at 41 Tavistock Crescent, Westbourne Green, Notting Hill. For some time after the film, the pub was renamed the Mother Black Cap, though it was sold and renamed several times before being demolished in 2010–2011.[35][36] The cafe where Marwood has breakfast at the beginning of the film is located at the corner of 136 Lancaster Road, W11 near the corner with Ladbroke Grove.[34] The scene where the police order Withnail and Marwood to "get in the back of the van" was filmed on the flyover near John Aird Court, Paddington.[34] Uncle Monty's house is actually the West House, Glebe Place, Chelsea, SW3, owned by Bernard Nevill.[37][34][35]

Shepperton

[edit]The police station interior was shot at Shepperton Studios.[38]

Music

[edit]The film score was composed by David Dundas and Rick Wentworth.[22] The film features a rare appearance of a recording by the Beatles, whose 1968 song "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" plays as the titular duo return to London and find Presuming Ed in the bath. The song, written and sung by George Harrison, was able to be included in the soundtrack due to Harrison's involvement as a producer.[39]

- "A Whiter Shade of Pale" (live) – King Curtis – 5:25

- "The Wolf" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 1:33

- "All Along the Watchtower" (reduced tempo) – The Jimi Hendrix Experience – 4:10

- "To the Crow" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 2:22

- "Voodoo Child (Slight Return)" (live) – The Jimi Hendrix Experience – 4:28

- "While My Guitar Gently Weeps" – The Beatles – 4:44

- "Marwood Walks" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 2:14

- "Monty Remembers" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 2:02

- "La Fite" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 1:10

- "Hang Out the Stars in Indiana" – Al Bowlly and New Mayfair Dance Orchestra – 1:35

- "Crow Crag" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 0:56

- "Cheval Blanc" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 1:15

- "My Friend" – Charlie Kunz – 1:28

- "Withnail's Theme" – David Dundas and Rick Wentworth – 2:40

Reception

[edit]On review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 92% based on 39 reviews, with an average rating of 8.40/10. The website's critical consensus reads, "Richard E. Grant and Paul McGann prove irresistibly hilarious as two misanthropic slackers in Withnail and I, a biting examination of artists living on the fringes of prosperity and good taste."[40]

Film critic Roger Ebert added the film to his Great Movies list, describing Grant's performance as a "tour de force" and Withnail as "one of the iconic figures in modern films".[41]

Robinson won the Best Screenplay award at the 1988 Evening Standard British Film Awards.

Legacy

[edit]The film is routinely regarded as being among the finest British films ever made, and its influence has been cited by several filmmakers as directly inspiring their work, among them Shane Black's The Nice Guys, James Ponsoldt's The End of the Tour, Todd Sklar's Awful Nice, Jay and Mark Duplass's Jeff, Who Lives at Home, John Bryant's The Overbrook Brothers, David Gordon Green's Pineapple Express, Alexander Payne's Sideways, and Tom DiCillo's Box of Moonlight.[42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49]

In 1999, the British Film Institute voted Withnail and I the 29th greatest British film of all time.[50] In 2001, Withnail and I was ranked 38th in Channel 4's 100 Greatest Films poll.[51] In 2008, the film was ranked number 118 in Empire's 500 Greatest Films of All Time list.[52] A 2009 poll by The Guardian among film critics and filmmakers voted it the second best British film of the last 25 years.[53] In 2011, Time Out London named it the seventh-greatest comedy film of all time.[54] In a 2014 poll, readers of Empire voted Withnail and I the 92nd greatest film.[55]

In 2016, Games Radar voted Withnail and I the 16th greatest comedy film of all time.[56] In a 2017 poll of 150 actors, directors, writers, producers and critics for Time Out magazine, the film was ranked the 15th best British film ever.[57] The line "We want the finest wines available to humanity, we want them here and we want them now", delivered by Richard E. Grant as Withnail, was voted the third favourite film one-liner in a 2003 poll of 1,000 film fans.[58]

There is a drinking game associated with the film.[59] The game consists of keeping up, drink for drink, with each alcoholic substance consumed by Withnail over the course of the film.[60][61] All told, Withnail is shown drinking roughly 9+1⁄2 glasses of red wine, one-half imperial pint (280 ml) of cider, one shot of lighter fluid (vinegar or overproof rum are common substitutes), 2+1⁄2 measures of gin, six glasses of sherry, thirteen drams of Scotch whisky and 1⁄2 pint of ale.[62][better source needed]

In 1992, filmmaker David Fincher attempted to create an unofficial reunion of sorts, when he attempted casting all three of the film's main characters in Alien 3. McGann and Brown appeared; however, Grant turned down his role, which eventually went to Charles Dance, who played the character of Clemens in the "spirit of Withnail".[63][self-published source?]

In 1996, the Los Angeles Times reported the film (and the associated drinking game) had achieved cult status prior to its home video re-release in the United States.[64]

In 2007, a digitally remastered version of the film was released by the UK Film Council. It was shown at over 50 cinemas around the UK on 11 September, as part of the final week of the BBC's Summer of British Film season.[65]

In 2010, McGann said that he sometimes meets viewers who believe the film was actually shot in the 1960s, saying "It comes from the mid-1980s, but it sticks out like a Smiths record. Its provenance is from a different era. None of the production values, none of the iconography, none of the style remotely has it down as an 80s picture."[66]

Stage adaptation

[edit]On 12 October 2023, it was announced that a stage adaptation would premiere at the Birmingham Repertory Theatre from 3 to 25 May 2024, adapted by Robinson and directed by Sean Foley.[67]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Smith, Adam (1 January 2012). "EMPIRE ESSAY: Withnail & I Review". Empire Online.

- ^ "Withnail and I (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 27 March 1987. Retrieved 15 January 2012.

- ^ "Withnail & I". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 27 November 2024.

- ^ Russell, Jamie (October 2003). "How "Withnail & I" Became a Cult". BBC. Retrieved 28 December 2010.

- ^ "Withnail and I". Handmade Films. Retrieved 17 January 2020.

- ^ Hoggard, Liz (17 September 2006). "Cult classic: Withnail and us". The Independent. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Withnail and I, extensively revised early draft of the original unpublished novel ink on paper". sothebys.com. Sotheby's. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "Earliest version of cult classic Withnail and I will go under the hammer at Sotheby's". breakingnews.ie. 12 December 2015. Archived from the original on 14 December 2015.

- ^ Murphy, Peter. "Interview with Bruce Robinson". laurahird.com. Archived from the original on 7 July 2007. Retrieved 7 August 2007.

- ^ Robinson, Bruce (1999). Withnail and Us. Channel 4. Event occurs at 1:31.

The movie takes place over, um... you know, two or three weeks and the reality of the story was over two or three years.

- ^ Robinson, Bruce (1999). Withnail and Us. Channel 4. Event occurs at 3:43.

The reason he's called Withnail is because when I was a little boy, um, I knew this bloke named Jonathan Withnall N-A-double-L and I 'cause I can't spell I called him 'Nail'. And he backed his Aston Martin into a police car coming out of a pub car park. And he was like the coolest guy I had ever met in my life so, consequently, that name stayed in my... my head.

- ^ "Romeo And Juliet (1968)". Film4. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2011.

- ^ a b Owen (2000).

- ^ Robinson, Bruce (22 September 2017). Withnail & I 30 years on: star Richard E Grant and director Bruce Robinson discuss the film. British Film Institute. Event occurs at 16:16.

And he leans over to me and says 'Are you a sponge or a stone?'

- ^ "Nude Au Pair's Secret Life". News of the World. 16 November 1969. Archived from the original on 7 October 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021 – via Twitter.

- ^ Owen (2000), p. 128.

- ^ Robinson, Bruce (9 July 2001). "'Withnail and I' (essay)". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Grant, Richard E. (1999). Withnail and Us. Channel 4. Event occurs at 5:34.

Paul McGann's character is Marwood, uh, but he's only referred to as 'I' in the story.

- ^ McGann, Paul (1999). Withnail and Us. Channel 4. Event occurs at 6:02.

Marwood was always like that little grain of sand...

- ^ Canby, Vincent (27 March 1987). "'Withnail and I', a Comedy". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 29 March 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Hewitt-McManus, Thomas: "Twenty things you might want to know about Withnail & I", DVD insert. Anchor Bay, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Withnail & I (1988)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 28 March 2016. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ Owen (2000), p. 109.

- ^ a b c d e Ong, Rachel. "Withnail and I in Camden". Time Out. Archived from the original on 20 February 2006. Retrieved 10 May 2008.

- ^ a b c "Withnail & I - Richard E Grant". Withnail-links.com. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Grant, Richard E. (1999). Withnail and Us. Channel 4. Event occurs at 12:35.

I've got pictures to prove it. I've never been fat. [...] I think that's part of the 'auteur' self-worship that directors indulge themselves in. [...] Bollocks to that!

- ^ "The World According To Grant". richard-e-grant.com. 17 January 2003.

- ^ Grant (1996), pp. 10–43.

- ^ "Withnail and I – Facts & Trivia". Withnail-links.com.

- ^ Owen (2000), pp. 108–109.

- ^ Scovell, Adam (11 April 2017). "In search of the Withnail & I locations 30 years on". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on 11 July 2019. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "Farmhouse from cult film for sale". BBC News. 19 January 2009. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ^ Wainwright, Martin (25 August 2009). "Some extremely distressing news: Withnail and I shrine falls through". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- ^ a b c d e Plowman (2021).

- ^ a b c "Withnail & I Filming Locations". movie-locations.com. The Worldwide Guide to Movie Locations. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "'We've run out of wine': Pub from Withnail and I demolished". Evening Standard. 23 February 2011. Archived from the original on 4 April 2017. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ "Property from the Late Professor Bernard Nevill & Withnail and I". Bellmans. Bellmanss. 14 January 2022. Retrieved 25 February 2022.

- ^ "Productions at Shepperton Studios". thestudiotour.com. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Pirnia, Garin (19 March 2016). "13 Loaded Facts About Withnail and I". Mental Floss. Retrieved 7 December 2017.

- ^ Withnail and I at Rotten Tomatoes

- ^ Ebert, Roger (25 March 2009). "A side-effect of alcoholism: My thumbs have gone weird!". RogerEbert.com. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ Keady, Martin (2 June 2017). "The Story Behind the Screenplay: Part 2". The Script Lab.

- ^ "Shane Black on Story: 212 Raising Stakes, Reversals, and Payoffs". PBS. 23 August 2012.

- ^ Keahon, Jena (31 January 2015). "Here are the Films That Inspired This Year's Sundance Filmmakers". IndieWire.

- ^ Turczyn, Coury (2 May 2018). "The making of Tom DiCillo's 'Box of Moonlight'". PopCultureMag.

- ^ "EP 155: Todd Sklar & Alex Rennie, David Gordon Green". Film Wax. 8 August 2013.

- ^ Gross, Terry (17 November 2011). "In Payne's 'Descendants,' Trouble In The Tropics". NPR.

- ^ "SXSW Interview: "The Overbrook Brothers" Director John Bryant". IndieWire. 9 March 2009.

- ^ McDonald, Duff (1 February 2019). "The Cult of Richard E. Grant's Withnail and I Is Finally Having Its Moment". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Best 100 British films - full list". 23 September 1999. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ "Top 100 films poll". BBC News. BBC. 26 November 2001. Archived from the original on 19 June 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2020.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies Of All Time". Empire. Archived from the original on 15 October 2012. Retrieved 28 May 2023.

- ^ Loach, Ken (29 August 2009). "Gallery: From Trainspotting to Sexy Beast - the best British films 1984-2009". The Guardian.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave; et al. (12 December 2018). "100 Best Comedy Movies". Time Out London. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ^ Green, Willow (2 June 2014). "The 301 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire. Retrieved 2 May 2020.

- ^ Seddon, Gem (1 November 2016). "The 25 best comedy movies to see before you die (of laughter)". Games Radar.

- ^ Calhoun, Dave; Huddleston, Tom; Jenkins, David; Adams, Derek; Andrew, Geoff; Davies, Adam Lee; Fairclough, Paul; Hammond, Wally; Kheraj, Alim; de Semlyen, Phil (10 September 2018). "The 100 best British films". Time Out. Retrieved 10 May 2019.

- ^ Paterson, Michael (10 March 2003). "Caine takes top billing for the greatest one-liner on screen". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 12 January 2022. Retrieved 25 October 2017.

- ^ Turner, Luke (15 July 2008). "Withnail and I comes of age". The Quietus. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Jonze, Tim (14 November 2011). "My favourite film: Withnail and I". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

I have to confess, I first heard about Withnail and I in terms of a drinking game – could you watch the film while matching the two lead characters shot for shot, pint for pint, Camberwell carrot for Camberwell carrot?

- ^ "The Withnail and I Drinking Game". Withnail-links.com. Retrieved 9 May 2009.

- ^ The Withnail and I Drinking Game, DVD Featurette. Anchor Bay Entertainment. 2006.

- ^ Hewitt-McManus, Thomas (2006). Withnail & I: Everything You Ever Wanted to Know But Were Too Drunk to Ask. Raleigh, North Carolina: Lulu Press Incorporated. p. 20. ISBN 978-1411658219.

- ^ Liebenson, Donald (10 November 1996). "'Withnail' and You: A Cult Fave Resurfaces". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 3 May 2020. Retrieved 3 May 2020.

- ^ "BBC – The Summer of British Film – What's On". BBC. Archived from the original on 22 April 2011. Retrieved 20 April 2011.

- ^ Dixon, Greg (21 October 2010). "Paul McGann coming in from the cult". The New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- ^ Wiegand, Chris (11 October 2023). "Withnail and I creator Bruce Robinson adapts film for the stage". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ "U.S. Dollar / British Pound Historical Reference Rates from Bank of England for 1987". Poundsterlinglive.com.

Sources cited

[edit]- Grant, Richard E. (1996). With Nails: The Film Diaries of Richard E. Grant. Picador. ISBN 0879519355.

- Plowman, Paul (2021). "Withnail & I Filming Locations". british-film-locations.com. Archived from the original on 8 November 2021.

- Owen, Alistair, ed. (2000). Smoking in Bed: Conversations with Bruce Robinson. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0747552592.

Further reading

[edit]- Barnes, Simon. "Withnail and Him". The Anthony Powell Newsletter. 88 (Autumn 2022): 8–11.

- Catterall, Ali; Wells, Simon (2001). Your Face Here: British Cult Movies Since The Sixties. Fourth Estate. ISBN 0007145543.

- Jackson, Kevin (2004). Withnail & I. BFI. ISBN 1844570355.

- Robinson, Bruce (1995). Withnail & I: The Original Screenplay. Bloomsbury. ISBN 0747524939.

- Robson, Maisie (2010). Withnail and the Romantic Imagination: A Eulogy. King's England Press. ISBN 978-1872438641.

- Benjamin, Toby (2023). Withnail and I: From Cult to Classic. Titan. ISBN 9781803362397.

External links

[edit]- Withnail and I at IMDb

- Withnail and I at the TCM Movie Database

- Withnail and I at Box Office Mojo

- Withnail and I at Rotten Tomatoes

- Withnail and I at the BFI's Screenonline

- Withnail and I an essay by Bruce Robinson at the Criterion Collection, from the introduction of the 10th anniversary publication of the screenplay

- Image gallery on BBC Cumbria

- Filming Locations for Withnail & I

- Withnail & I – 25 Years On

- Withnail and I (Original Soundtrack) at Discogs (list of releases)

- Withnail and I at MusicBrainz (list of releases)

- 1987 films

- 1987 black comedy films

- 1987 comedy-drama films

- 1987 directorial debut films

- 1987 independent films

- 1987 LGBTQ-related films

- British comedy-drama films

- British LGBTQ-related films

- Films directed by Bruce Robinson

- Films with screenplays by Bruce Robinson

- British black comedy films

- British buddy comedy-drama films

- Films about actors

- Films about alcoholism

- Films set in the Lake District

- Films set in London

- Films set in 1969

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in London

- British independent films

- HandMade Films films

- Films set in country houses

- 1980s English-language films

- 1980s British films

- English-language black comedy films

- English-language independent films