Monarchy of Pakistan

| Monarchy of Pakistan | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Details | |

| Style | His Majesty 1947–1952 Her Majesty 1952–1956 |

| First monarch | George VI |

| Last monarch | Elizabeth II |

| Formation | 14 August 1947 |

| Abolition | 23 March 1956 |

From 1947 to 1956, the Dominion of Pakistan was a self-governing country within the Commonwealth of Nations that shared a monarch with the United Kingdom and the other Dominions of the Commonwealth. The monarch's constitutional roles in Pakistan were mostly delegated to a vice-regal representative, the governor-general of Pakistan.

The dominion was created by the Indian Independence Act 1947, which divided British India into two independent sovereign states of India and Pakistan. The monarchy was abolished on 23 March 1956, when Pakistan became a republic within the Commonwealth with a president as its head of state.

History

[edit]Reign of George VI (1947–1952)

[edit]

Under the Indian Independence Act 1947, British India was to be divided into the independent sovereign states of India and Pakistan. From 1947 to 1952, King George VI was the sovereign of Pakistan, with Pakistan sharing the sovereign with the United Kingdom and the other Dominions of the Commonwealth of Nations.[1][2][3]

To mark the independence of Pakistan, the King sent a message of congratulations to its people, which was read by Lord Mountbatten in the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan on 14 August 1947. In his message, the King said in "achieving your independence by agreement, you have set an example to all freedom-loving people throughout the world". He told the Pakistani people to be "assured always of my sympathy and support as I watch your continuing efforts to advance the cause of humanity".[4]

The King appointed Mohammad Ali Jinnah as the governor-general of Pakistan and authorised him to exercise and perform all the powers and duties as his representative in Pakistan. Mohammad Ali Jinnah took the following oath of office:[5]

"I, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, do solemnly affirm true faith and allegiance to the Constitution of Pakistan as by law established and that I will be faithful to His Majesty King George VI, in the office of governor general of Pakistan."

Jinnah died of tuberculosis on 11 September 1948, while in office.[6] The King confirmed the appointment of Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin as the next governor-general by a Royal decree which said:[7]

"On the advice of the Prime Minister of Pakistan, His Majesty the King is pleased to appoint Khwaja Nazimuddin as acting governor-general of Pakistan in the vacancy occasioned by the sad demise of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah."

In 1951, Sir Khwaja Nazimuddin resigned from the post of governor-general to become the new prime minister. The King appointed Sir Ghulam Mohammed as the third governor-general of Pakistan.[8]

King George VI died in his sleep in the early hours of 6 February 1952. The King's death was deeply mourned in Pakistan. In view of the King's death, all government offices in Pakistan remained closed on 7 February. All places of amusement and business-houses closed, and the government cancelled all official engagements. Most Pakistani newspapers were issued with black borders on 7 February. On 15 February, the day of the funeral, a national two minutes' silence was observed throughout Pakistan, and a salute of 56 guns was fired, one for each year of the King's life. All Pakistani flags were flown at half-mast till the day of the funeral.[9][10][11]

In the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, the Dominion's federal legislature, Prime Minister Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin said that the King's reign will always be remembered by Pakistanis as "the period during which the Muslims of the Indo-Pakistan Subcontinent carved out a homeland for themselves".[12]

Reign of Elizabeth II (1952–1956)

[edit]

Following George VI's death on 6 February 1952, his elder daughter Princess Elizabeth became the new monarch of Pakistan.[3][13] She was proclaimed Queen throughout her realms, including in Pakistan, where she was honoured with a 21-gun salute on 8 February.[14][11][15][9]

Andrew Michie wrote in 1952 that "Elizabeth II embodies in her own person many monarchies", as she was Queen of the United Kingdom, but was also equally Queen of Pakistan. He added that it was "now possible for Elizabeth II to be, in practice as well as theory, equally Queen in all her realms".[16]

During her coronation in 1953, Elizabeth II was crowned as Queen of Pakistan and other independent Commonwealth realms.[17] In her Coronation Oath, the Queen promised "to govern the Peoples of … Pakistan … according to their respective laws and customs".[18] The Queen's coronation gown was embroidered with the floral emblems of each Commonwealth nation, and it featured the three emblems of Pakistan: wheat, in oat-shaped diamante and fronds of golden crystal; cotton, made in silver with leaves of green silk; and jute, embroidered in green silk and golden thread.[19][20]

The Standard of Pakistan at the Coronation was borne by Mirza Abol Hassan Ispahani.[21] Major-General Mohd. Yusuf Khan served as the head of Pakistan's Coronation Contingent.[22] Pakistani naval vessels HMPS Zulfiqar and HMPS Jhelum took part in the Coronation Review of the fleet at Spithead on 15 June 1953,[23][24][25] which cost approximately 81,000 rupees.[26]

Eighty seats were reserved for Pakistanis in the Abbey for the Coronation.[22] Prime Minister Mohammad Ali Bogra, also attended the Coronation on 2 June, along with his wife and two sons,[27] after which he attended the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference from 3 June to 9 June 1953, in London.[28]

The Government of Pakistan spent approximately 482,000 rupees for the Queen's Coronation. Prime Minister Bogra justified the expenditure by saying that Pakistan being a member of the Commonwealth "has to fall in line with other sister Dominions on such occasions".[29]

In 1953, Governor-General Sir Ghulam Muhammad dismissed Prime Minister Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin for attempting to equalise the power of West and East Pakistan. The prime minister attempted to reverse this decision by pleading to the Queen, but she refused to intervene. Citing this incident, Akhilesh Pillalamarri of The Diplomat wrote that "She deliberately kept from interfering in the country and her governors-general were presidents of Pakistan in all but name."[13]

At the 1955 Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference, the Prime Minister of Pakistan informed fellow Commonwealth leaders that Pakistan would be adopting a republican constitution, but desired Pakistan to remain a member of the Commonwealth. The Commonwealth leaders issued a declaration on 4 February, in which it was said:[30][31]

The Government of Pakistan have informed the other Governments of the Commonwealth of the intention of the Pakistan people that under the new Constitution which is about to be adopted, Pakistan shall become a sovereign independent Republic. The Government of Pakistan, have, however, declared and affirmed Pakistan's desire to continue her full membership of the Commonwealth of Nations and her acceptance of the Queen as the symbol of the free association of its independent member nations, and as such the Head of the Commonwealth.

In 1955, the Pakistani Government recommended to the Queen that Major-General Iskander Mirza should succeed Sir Ghulam Muhammad as the next governor-general, the Queen's representative in Pakistan. On 19 September, it was officially announced that the Queen had appointed Iskander Mirza to be the governor-general, with effect from 6 October 1955. Mirza took office after the Royal sign-manual from the Queen was read out.[32][33][34]

The Queen also congratulated the retiring governor-general, Sir Ghulam Mohammad, on the manner in which he carried out his duties as the governor-general.[35]

Abolition

[edit]The Pakistani monarchy was abolished on the adoption of a republican constitution on 23 March 1956.[36] Pakistan became a republic within the Commonwealth of Nations. The Queen sent a message to the new president Major-General Mirza, in which she said: "I have followed with close interest the progress of your country since its establishment ... It is a source of great satisfaction to me to know that your country intends to remain within the Commonwealth. I am confident that Pakistan and other countries of the Commonwealth will continue to thrive and to benefit from their mutual association".[37]

The Queen visited Pakistan as Head of the Commonwealth in 1961 and 1997, accompanied by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh.[38]

Pakistan left the Commonwealth in 1972 over the issue of the former East Pakistan province becoming independent as Bangladesh. It rejoined in 1989, then was suspended from the Commonwealth twice: firstly from 18 October 1999 to 22 May 2004 and secondly from 22 November 2007 to 22 May 2008.[39]

-

The Queen with Nazir Ahmed, chairman of the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission

-

Queen Elizabeth II visiting Chittagong, East Pakistan, in 1961

-

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge during their tour of Pakistan in 2019

Title

[edit]

Before 1953, the monarch's title was same throughout all realms and territories. It was agreed at the Commonwealth Economic Conference in London in December 1952 that each of the Queen's realms, including Pakistan, could adopt its own royal titles for the monarch.[40][41] The Queen's official title in Pakistan, per the official proclamation in The Gazette of Pakistan on 29 May 1953, was "Elizabeth the Second, Queen of the United Kingdom and of Her other Realms and Territories, Head of the Commonwealth".[40][42]

As Pakistan was a Muslim-majority country, the phrases by the Grace of God and Defender of the Faith were omitted. The title "Defender of the Faith" reflected the Sovereign's position as the supreme governor of the Church of England, who is thus formally superior to the archbishop of Canterbury.[40]

Constitutional role

[edit]Pakistan was one of the realms of the Commonwealth of Nations that shared the same person as Sovereign and head of state.[2]

Effective with the Indian Independence Act 1947, no British government minister could advise the sovereign on any matters pertaining to Pakistan, meaning that on all matters of the Dominion of Pakistan, the monarch was advised solely by Pakistani ministers of the Crown.[43] All Pakistani bills required Royal assent.[5] The Pakistani monarch was represented in the Dominion by the governor-general of Pakistan, who was appointed by the monarch on the advice of the Pakistani Government.[44]

The Crown and Government

[edit]

The Pakistani monarch and the federal legislature constituted the Parliament of Pakistan. All executive powers of Pakistan rested with the sovereign.[45] All laws in Pakistan were enacted only with the granting of Royal Assent, done by the governor-general on behalf of the sovereign.[46] The governor-general was also responsible for summoning, proroguing, and dissolving the Federal Legislature.[46] The governor-general had the power to choose and appoint the Council of Ministers and could dismiss them under his discretion. All Pakistani ministers of the Crown held office at the pleasure of the governor-general.[46]

The Crown and Foreign affairs

[edit]Pakistani ambassadors and representatives to foreign countries were accredited by the monarch in his or her capacity as the Sovereign of Pakistan and Pakistani envoys sent abroad required royal approval. The letters of credence and letters of recall were formerly issued by the monarch.[47][48]

The Crown and the Courts

[edit]Within the Commonwealth realms, the sovereign is responsible for rendering justice for all her subjects, and is thus traditionally deemed the fount of justice.[49] In Pakistan, criminal offences were legally deemed to be offences against the sovereign and proceedings for indictable offences were brought in the sovereign's name in the form of The Crown versus [Name].[50][51] Hence, the common law held that the sovereign "can do no wrong"; the monarch cannot be prosecuted in his or her own courts for criminal offences.[52] The governor-general of Pakistan was also exempted from any proceedings against him in any Pakistani court.[46]

Vice-regal residences

[edit]The representative of the Pakistani monarch officially resided at Governor-General's House, in the city of Karachi. All four governors-general lived there until 1956, when the monarchy was abolished, and the residence was renamed President's House.[53]

All oath taking ceremonies were held at the Darbar Hall of Governor-General's House. The Hall also contains a throne which was made for King Edward VII during his tour of India as Prince of Wales in 1876, and was also used by Queen Mary during the Delhi Durbar in 1911. All governors-general took salutes at the terrace of the house on national days as the contingents of guards marched past.[53]

Cultural role

[edit]The Crown and Honours

[edit]Within the Commonwealth realms, the monarch is deemed the fount of honour.[54] Similarly, the monarch, as Sovereign of Pakistan, conferred awards and honours in Pakistan in his or her name. Most of them were awarded on the advice of "His Majesty's Pakistan Ministers" (or "Her Majesty's Pakistan Ministers").[55][56][57]

- See also

The Crown and the Defence Force

[edit]The Crown sat at the pinnacle of the Pakistan Defence Force. It was reflected in Pakistan's naval vessels, which bore the prefix HMPS, i.e., Her Majesty's Pakistan Ship (or His Majesty's Pakistan Ship during the reign of George VI).[58] The Pakistan Navy and the Pakistan Air Force were known as Royal Pakistan Navy and Royal Pakistan Air Force respectively. The prefix "Royal" was dropped when the Pakistani monarchy was abolished.[59][60]

Pakistani royal symbols

[edit]-

The flag of the governor-general of Pakistan featuring St Edward's Crown

-

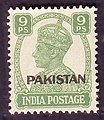

A Pakistani stamp featuring King George VI

-

Flying badge of the Royal Pakistan Air Force (RPAF) featuring the Tudor Crown

-

The obverse of the 1949 Pakistan Medal bearing the royal cypher of King George VI

-

The badge of Baluch Regiment, Pakistan Army, featuring the Tudor Crown

List of Pakistani monarchs

[edit]| No. | Portrait | Regnal name (Birth–Death) |

Reign | Full name | Consort | Royal House | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||||

| 1 |

|

George VI (1895–1952) |

14 August 1947 | 6 February 1952 | Albert Frederick Arthur George | Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon | Windsor |

| Governors-general: Muhammad Ali Jinnah, Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, Sir Ghulam Muhammad Prime ministers: Liaquat Ali Khan, Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin | |||||||

| 2 |

|

Elizabeth II (1926–2022) |

6 February 1952 | 23 March 1956 | Elizabeth Alexandra Mary | Philip Mountbatten | Windsor |

| Governors-general: Sir Ghulam Muhammad, Iskander Mirza Prime ministers: Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin, Mohammad Ali Bogra, Chaudhry Muhammad Ali | |||||||

See also

[edit]- List of heads of state of Pakistan

- List of sovereign states headed by Elizabeth II

- List of prime ministers of George VI

- List of prime ministers of Elizabeth II

- List of Commonwealth visits made by Elizabeth II

- List of the last monarchs in Asia

References

[edit]- ^ Matthew, H. C. G. (September 2004). "George VI". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33370. Retrieved 20 April 2008.

India and Pakistan remained among the king's dominions but both were set on republican courses, becoming republics within the Commonwealth in 1950 and 1956 respectively.

(Subscription or UK public library membership required.) - ^ a b Kumarasingham, Harshan (2013), THE 'TROPICAL DOMINIONS': THE APPEAL OF DOMINION STATUS IN THE DECOLONISATION OF INDIA, PAKISTAN AND CEYLON, vol. 23, Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, p. 223, JSTOR 23726109

- ^ a b Aman M. Hingorani (2016), Unravelling the Kashmir Knot, p. 184, ISBN 9789351509721

- ^ "His Excellency The Governor-General's Address to the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan" (PDF). National Assembly of Pakistan. 14 August 1947. Retrieved 26 June 2022.

- ^ a b "Transfer of power and Jinnah". DAWN. 4 February 2013. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Mohammad Ali Jinnah (1876-1948)". BBC. Retrieved 22 August 2021.

- ^ Three Presidents, Three Prime Ministers: Fragmentary Recollections of the Author's Days with Chaudhry Muhammad Ali ..., Dost Publications, 1996, p. 15, ISBN 9789694960074

- ^ Current Biography Yearbook, H. W. Wilson Company, 1954, p. 466

- ^ a b The Table: Volumes 20-23, Butterworth., 1952, p. 112

- ^ Denis Judd (2012), George VI, I.B.Tauris, p. LV, ISBN 9780857730411

- ^ a b Islam: 1950-1952, Archive Editions, 2004, p. 513, ISBN 9781840970708

- ^ The Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debate: Official Report · Volume 1, vol. 1, Manager of Publications, 1952, p. 2

- ^ a b Pillalamarri, Akhilesh. "When Elizabeth II Was Queen of Pakistan". The Diplomat. Retrieved 27 August 2021.

- ^ Barker, Brian (1976), When the Queen was crowned, Routledge & Kegan Paul, p. 29, ISBN 9780710083975

- ^ Select Documents on the Constitutional History of the British Empire and Commonwealth: The dominions and India since 1900, Greenwood Press, 1985, p. 183, ISBN 9780313273261

- ^ Michie, Allan Andrew (1952). The Crown and the People. London: Secker & Warburg. p. 52. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ^ "The Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II". YouTube. 27 January 2008. Retrieved 16 May 2014.

- ^ "The Form and Order of Service that is to be performed and the Ceremonies that are to be observed in the Coronation of Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II in the Abbey Church of St. Peter, Westminster, on Tuesday, the second day of June, 1953". Oremus.org. Retrieved 3 February 2013.

- ^ "Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Gown". Fashion Era. Archived from the original on 6 June 2011. Retrieved 30 April 2011.

- ^ Hardman, Robert (2018), Queen of the World, Random House, ISBN 9781473549647

- ^ "No. 40020". The London Gazette (1st supplement). 17 November 1953. p. 6240.

- ^ a b Pakistan. Constituent Assembly (1947-1954). Legislature (1953), The Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debate: Official Report · Volume 2, p. 469

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Souvenir Programme, Coronation Review of the Fleet, Spithead, 15th June 1953, HMSO, Gale and Polden

- ^ Day, A. (22 May 1953). "Coronation Review of the Fleet" (PDF). Cloud Observers Association. Retrieved 3 May 2015.

- ^ Pakistan, Pakistan Publications, 1952, p. 167

- ^ Pakistan. Constituent Assembly (1947-1954). Legislature (1953), The Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debate: Official Report · Volume 2, p. 18

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Pakistan Affairs: Volumes 5-6, vol. 6, Information Division, Embassy of Pakistan, 1951, p. 1

- ^ Schofield, Victoria (2000). "Special Status". Kashmir in Conflict: India, Pakistan and the Unending War. I.B.Tauris. p. 85. ISBN 9781860648984. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- ^ Pakistan. Constituent Assembly (1947-1954). Legislature (1953), Debates. Official Report, p. 890

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Commonwealth Secretariat (1987), The Commonwealth at the Summit: Communiqués of Commonwealth Heads of Government Meetings, 1944-1986, Commonwealth Secretariat, p. 44, ISBN 9780850923179

- ^ Commonwealth Survey: Volume 1, Central Office of Information, 1955, p. 115

- ^ Aḥmad Salīm (1997), Iskander Mirza, Rise and Fall of a President, Gora Publishers, pp. 220, 225

- ^ Syed Nur Ahmad (2019), From Martial Law To Martial Law: Politics In The Punjab, 1919-1958, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780429716560,

Then Muhammad Ali presented the letter to the cabinet and proposed that the cabinet recommend to the Queen that the application for leave be accepted and that General Iskandar Mirza be appointed acting governor-general. The cabinet agreed and the decision was announced immediately. The next day the Queen gave her sanction and Iskandar Mirza took the oath of office.

- ^ Aḥmad Salīm (1997), Iskander Mirza, Rise and Fall of a President, Gora Publishers, p. 220

- ^ Iskandar Mirzā (1997), Iskander Mirza Speaks: Speeches, Statements and Private Papers, Gora Publishers, p. 294

- ^ John Stewart Bowman (2000). Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture. Columbia University Press. p. 372. ISBN 978-0-231-11004-4. Retrieved 22 March 2011.

- ^ "Queen Elizabeth Sends Message", Pakistan Affairs, vol. 9, no. 6, Information Division, Embassy of Pakistan, p. 7, 9 April 1956

- ^ "Commonwealth visits since 1952". Official website of the British monarchy. Archived from the original on 12 April 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2012.

- ^ "Profile: Commonwealth of Nations - Timeline". BBC News. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Wheare, K.C. (1953). "The Nature and Structure of the Commonwealth". American Political Science Review. 47 (4): 1022. doi:10.2307/1951122. JSTOR 1951122. S2CID 147443295.

- ^ Queen & Commonwealth: 90 Glorious Years (PDF), Henley Media Group, 2016, p. 61, ISBN 9780992802066

- ^ The Gazette of Pakistan, Extraordinary, Karachi, Friday, May 29, 1953

- ^ Syed Nur Ahmad (2019), From Martial Law To Martial Law: Politics In The Punjab, 1919-1958, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 9780429716560,

The British High Commissioner treated Nazimuddin with the utmost respect and after hearing his plea agreed that Queen Elizabeth was monarch of both Britain and Pakistan. However, it was necessary to make a distinction between the two. If Nazimuddin wished to put his case before the Queen of Pakistan he was free to do so, but the High Commissioner was a representative of the Queen of Great Britain only and was in Pakistan in that capacity alone. He was not the representative of the Queen of Pakistan and could not be an intermediary for talks between Nazimuddin and his Queen.

- ^ Karl Von Vorys (1965), Political development in Pakistan, Princeton University Press, p. 272, ISBN 9781400876389

- ^ Allen McGrath (1996), The Destruction of Pakistan's Democracy, Oxford University Press, p. 270, ISBN 9780195775839

- ^ a b c d Bin Sayeed, Khalid (1955), "The Governor-General of Pakistan", Pakistan Horizon, 8 (2), Pakistan Institute of International Affairs: 330–339, JSTOR 41392177

- ^ Marjorie Millace Whiteman (1963), Digest of International Law: Volume 1, U.S. Department of State, p. 510

- ^ Department of State Publication: Issue 8512, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1970, p. 70

- ^ Davis, Reginald (1976), Elizabeth, our Queen, Collins, p. 36, ISBN 9780002112338

- ^ The Constituent Assembly (Legislature) of Pakistan Debate: Official Report · Volume 1, Manager of Publications, 1952, p. 535

- ^ Pakistan Law Reports: Lahore series · Volume 9, Part 2, Government Book Depot., 1956, pp. 1159, 1161

- ^ Halsbury's Laws of England, volume 12(1): "Crown Proceedings and Crown Practice", paragraph 101

- ^ a b "History of the Governor House". Governor of Sindh. Archived from the original on 3 February 2011.

- ^ Commonwealth Journal: The Journal of the Royal Commonwealth Society · Volumes 12-14, Royal Commonwealth Society, 1969, p. 99

- ^ "No. 39737". The London Gazette (6th supplement). 30 December 1952. p. 49.

- ^ "No. 40057". The London Gazette (5th supplement). 29 December 1953. p. 49.

- ^ "No. 40673". The London Gazette (5th supplement). 30 December 1955. p. 49.

- ^ Shukal, Om Prakash (2007), Excellence In Life, Gyan Publishing House, p. 332, ISBN 9788121209632

- ^ "PN History". Pakistan Navy. Retrieved 20 August 2021.

- ^ "Infancy to Independence". Pakistan Air Force. Retrieved 20 August 2021.