Tally marks

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2012) |

Tally marks, also called hash marks, are a form of numeral used for counting. They can be thought of as a unary numeral system.

They are most useful in counting or tallying ongoing results, such as the score in a game or sport, as no intermediate results need to be erased or discarded. However, because of the length of large numbers, tallies are not commonly used for static text. Notched sticks, known as tally sticks, were also historically used for this purpose.

Early history

[edit]Counting aids other than body parts appear in the Upper Paleolithic. The oldest tally sticks date to between 35,000 and 25,000 years ago, in the form of notched bones found in the context of the European Aurignacian to Gravettian and in Africa's Late Stone Age.

The so-called Wolf bone is a prehistoric artifact discovered in 1937 in Czechoslovakia during excavations at Dolní Věstonice, Moravia, led by Karl Absolon. Dated to the Aurignacian, approximately 30,000 years ago, the bone is marked with 55 marks which may be tally marks. The head of an ivory Venus figurine was excavated close to the bone.[1]

The Ishango bone, found in the Ishango region of the present-day Democratic Republic of Congo, is dated to over 20,000 years old. Upon discovery, it was thought to portray a series of prime numbers. In the book How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years, Peter Rudman argues that the development of the concept of prime numbers could only have come about after the concept of division, which he dates to after 10,000 BC, with prime numbers probably not being understood until about 500 BC. He also writes that "no attempt has been made to explain why a tally of something should exhibit multiples of two, prime numbers between 10 and 20, and some numbers that are almost multiples of 10."[2] Alexander Marshack examined the Ishango bone microscopically, and concluded that it may represent a six-month lunar calendar.[3]

Clustering

[edit]

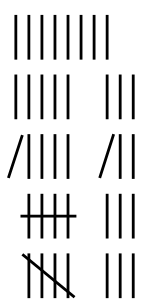

Tally marks are typically clustered in groups of five for legibility. The cluster size 5 has the advantages of (a) easy conversion into decimal for higher arithmetic operations and (b) avoiding error, as humans can far more easily correctly identify a cluster of 5 than one of 10.[citation needed]

-

Tally marks representing (from left to right) the numbers 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 that was used in most of Europe, the Anglosphere, and Southern Africa.[citation needed] In some variants, the diagonal/horizontal slash is used on its own when five or more units are added at once.

-

Tally marks used in France, Portugal, Spain, and their former colonies, including Latin America. 1 to 5 and so on. These are most commonly used for registering scores in card games, like Truco.

Writing systems

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Numeral systems |

|---|

| List of numeral systems |

Roman numerals, the Brahmi and Chinese numerals for one through three (一 二 三), and rod numerals were derived from tally marks, as possibly was the ogham script.[7]

Base 1 arithmetic notation system is a unary positional system similar to tally marks. It is rarely used as a practical base for counting due to its difficult readability.

The numbers 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ... would be represented in this system as[8]

- 1, 11, 111, 1111, 11111, 111111 ...

Base 1 notation is widely used in type numbers of flour; the higher number represents a higher grind.

Unicode

[edit]In 2015, Ken Lunde and Daisuke Miura submitted a proposal to encode various systems of tally marks in the Unicode Standard.[9] However, the box tally and dot-and-dash tally characters were not accepted for encoding, and only the five ideographic tally marks (正 scheme) and two Western tally digits were added to the Unicode Standard in the Counting Rod Numerals block in Unicode version 11.0 (June 2018). Only the tally marks for the numbers 1 and 5 are encoded, and tally marks for the numbers 2, 3 and 4 are intended to be composed from sequences of tally mark 1 at the font level.

| Counting Rod Numerals[1][2] Official Unicode Consortium code chart (PDF) | ||||||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | A | B | C | D | E | F | |

| U+1D36x | 𝍠 | 𝍡 | 𝍢 | 𝍣 | 𝍤 | 𝍥 | 𝍦 | 𝍧 | 𝍨 | 𝍩 | 𝍪 | 𝍫 | 𝍬 | 𝍭 | 𝍮 | 𝍯 |

| U+1D37x | 𝍰 | 𝍱 | 𝍲 | 𝍳 | 𝍴 | 𝍵 | 𝍶 | 𝍷 | 𝍸 | |||||||

| Notes | ||||||||||||||||

See also

[edit]- History of writing ancient numbers

- Abacus

- Australian Aboriginal enumeration

- Carpenters' marks

- Cherty i rezy

- Chuvash numerals

- Counting rods

- Finger counting

- Hangman (game)

- History of communication

- History of mathematics

- Lebombo bone

- List of international common standards

- Paleolithic tally sticks

- Prehistoric numerals

- Quipu

- Roman numerals

- Tally stick

Notes

[edit]- ^ This character was apparently chosen purely due to appropriateness of the physical process of writing it using the conventional stroke-order system—i.e., the physical movements of the strokes have a distinct alternation right-down-right-down-right working down the character, but the semantics of the character have no particular relation to the concept of "5" (neither in the character etymology nor the word etymology, which in languages using Chinese characters are two originally-separate-but-historically-complexly-interacting things). By contrast, the character for "five", 五, which looks like it also has 5 distinct lines, has only 4 strokes when written using conventional stroke-order.)

References

[edit]- ^ *Graham Flegg, Numbers: their history and meaning, Courier Dover Publications, 2002 ISBN 978-0-486-42165-0, pp. 41-42.

- ^ Rudman, Peter Strom (2007). How Mathematics Happened: The First 50,000 Years. Prometheus Books. p. 64. ISBN 978-1-59102-477-4.

- ^ Marshack, Alexander (1991): The Roots of Civilization, Colonial Hill, Mount Kisco, NY.

- ^ Hsieh, Hui-Kuang (1981) "Chinese tally mark", The American Statistician, 35 (3), p. 174, doi:10.2307/2683999

- ^ Ken Lunde, Daisuke Miura, L2/16-046: Proposal to encode five ideographic tally marks, 2016

- ^ Schenck, Carl A. (1898) Forest mensuration. The University Press. p. 47. (Note: The linked reference appears to actually be "Bulletin of the Ohio Agricultural Experiment Station", Number 302, August 1916)

- ^ Macalister, R. A. S., Corpus Inscriptionum Insularum Celticarum Vol. I and II, Dublin: Stationery Office (1945).

- ^ Hext, Jan (1990), Programming Structures: Machines and programs, vol. 1, Prentice Hall, p. 33, ISBN 9780724809400.

- ^ Lunde, Ken; Miura, Daisuke (30 November 2015). "Proposal to encode tally marks" (PDF). Unicode Consortium.

![In the dot and line (or dot-dash) tally, dots represent counts from 1 to 4, lines 5 to 8, and diagonal lines 9 and 10. This method is commonly used in forestry and related fields.[6]](/uploads/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e4/Dot_and_line_tally_marks.jpg/120px-Dot_and_line_tally_marks.jpg?auto=webp)