History of Pakistan (1947–present)

It has been suggested that Political history of Pakistan be merged into this article. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2024. |

| History of modern Pakistan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-independence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Post-independence | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| See also | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The history of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan began on 14 August 1947 when the country came into being in the form of Dominion of Pakistan within the British Commonwealth as the result of Pakistan Movement and the partition of India. While the history of the Pakistani Nation according to the Pakistan government's official chronology started with the Islamic rule over Indian subcontinent by Muhammad bin Qasim[1] which reached its zenith during Mughal Era. In 1947, Pakistan consisted of West Pakistan (today's Pakistan) and East Pakistan (today's Bangladesh). The President of All-India Muslim League and later the Pakistan Muslim League, Muhammad Ali Jinnah became Governor-General while the secretary general of the Muslim League, Liaquat Ali Khan became Prime Minister. The constitution of 1956 made Pakistan an Islamic democratic country.

Pakistan faced a civil war and Indian military intervention in 1971 resulting in the secession of East Pakistan as the new country of Bangladesh. The country has also unresolved territorial disputes with India, resulting in four conflicts. Pakistan was closely tied to the United States in the Cold War. In the Afghan-Soviet War, it supported the Sunni Mujahideens and played a vital role in the defeat of Soviet Forces and forced them to withdraw from Afghanistan. The country continues to face challenging problems including terrorism, poverty, illiteracy, corruption and political instability. Terrorism due to War of Afghanistan damaged the country's economy and infrastructure to a great extent from 2001 to 2009 but Pakistan is once again developing.

Pakistan is a nuclear power as well as a declared nuclear-weapon state, having conducted six nuclear tests in response to five nuclear tests of their rival Republic of India in May 1998. The first five tests were conducted on 28 May and the sixth one on 30 May. With this status, Pakistan is seventh in world, second in South Asia and the only country in the Islamic World. Pakistan also has the sixth-largest standing armed forces in the world and is spending a major amount of its budget on defense. Pakistan is the founding member of the OIC, the SAARC and the Islamic Military Counter Terrorism Coalition as well as a member of many international organisations including the UN, the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, the Commonwealth of Nations, the ARF, the Economic Cooperation Organization and many more.

Pakistan is a middle power which is ranked among the emerging and growth-leading economies of the world and is backed by one of the world's largest and fastest-growing middle class. It has a semi-industrialized economy with a well-integrated agriculture sector. It is one of the Next Eleven, a group of eleven countries that, along with the BRICs, have a high potential to become the world's largest economies in the 21st century.Although Pakistan is facing a severe economic crisis since 2022 which has further detoriated its economic situation,Geographically Pakistan is also an important country and a source of contact between Middle East, Central Asia, South Asia and East Asia.

Pakistan Movement

Important leaders in the Muslim League highlighted that Pakistan would be a "New Madinah", in other words the second Islamic state established after the Prophet Muhammad's creation of an Islamic state of Madinah which was later developed into Rashidun Caliphate. Pakistan was popularly envisaged as an Islamic utopia, a successor to the defunct Islamic Caliphate and a leader and protector of the entire Islamic world. Islamic scholars debated over whether it was possible for the proposed Pakistan to truly become an Islamic state.[2][3]

Another motive and reason behind the Pakistan Movement and Two Nation Theory is the ideology of pre-partition Muslims and leaders of Muslim League including Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Allama Iqbal is that, to re-establish the Muslim rule in South Asia. Once Jinnah said in his speech:

The Pakistan Movement started when the first Muslim (Muhammad bin Qasim) put his foot on the soil of Sindh, the gateway of Islam in India.[4][5]

— Muhammad Ali Jinnah

That is why Jinnah is considered the "great Muslim ruler" in the Indian subcontinent after Emperor Aurangzeb by Pakistanis.[6] This is also the reason that the Pakistani government's official chronology declares that the foundation of Pakistan was laid in 712 AD[1] by Muhammad bin Qasim after Islamic conquest of Sindh and that these conquests at their zenith conquered the entire Indian subcontinent during Muslim Mughal Era.

While the Indian National Congress's (Congress) top leadership had been imprisoned following the 1942 Quit India Movement, there was intense debate among Muslims over the creation of a separate homeland.[3] The All India Azad Muslim Conference represented nationalist Muslims who, in April 1940, gathered in Delhi to voice their support for a united India.[7] Its members included several Islamic organisations in India, as well as 1400 nationalist Muslim delegates.[8][9] The Deobandis and their ulema, who were led by Husain Ahmad Madani, were opposed to the creation of Pakistan and the two-nation theory, instead promulgating composite nationalism and Hindu-Muslim unity. According to them Muslims and Hindus could be one nation and Muslims were only a nation of themselves in the religious sense and not in the territorial sense.[10][11][12] Some Deobandis such as Ashraf Ali Thanwi, Mufti Muhammad Shafi and Shabbir Ahmad Usmani dissented from the position of Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind and were supportive of the Muslim League's demand to create a separate homeland for Muslims.[13][14] Many Barelvis and their ulema,[15] though not all Barelvis and Barelvi ulema,[16] supported the creation of Pakistan.[17] The pro-separatist Muslim League mobilized pirs and Sunni scholars to demonstrate that their view that India's Muslim masses wanted a separate country was in the majority, in their eyes.[14] Those Barelvis who supported the creation of a separate Muslim homeland in colonial India believed that any co-operation with Hindus would be counter productive.[18]

Muslims who were living in provinces where they were demographically a minority, such as the United Provinces where the Muslim League enjoyed popular support,[19] were assured by Jinnah that they could remain in India, migrate to Pakistan or continue living in India but as Pakistani citizens. The Muslim League had also proposed the hostage population theory. According to this theory the safety of India's Muslim minority would be ensured by turning the Hindu minority in the proposed Pakistan into a 'hostage' population who would be visited by retributive violence if Muslims in India were harmed.[3][20]

The Pakistani demand resulted in the Muslim League becoming pitted against both the Congress and the British.[21] In the Constituent Assembly elections of 1946, the Muslim League won 425 out of 496 seats reserved for Muslims, polling 89.2% of the total votes.[22] Congress had hitherto refused to acknowledge the Muslim League's claim of being the representative of Indian Muslims but finally recognised to the League's claim after the results of this election. The Muslim League's demand for the creation of Pakistan had received overwhelming popular support from India's Muslims, especially those Muslims who were living in provinces where they were a minority. The 1946 election in British India was essentially a plebiscite among Indian Muslims over the creation of Pakistan.[23][24][25]

The British, while not approving of a separate Muslim homeland, appreciated the simplicity of a single voice to speak on behalf of India's Muslims.[26] To preserve India's unity the British arranged the Cabinet Mission Plan.[27] According to this plan India would be kept united but would be heavily decentralised with separate groupings of autonomous Hindu and Muslim majority provinces. The Muslim League accepted this plan as it contained the 'essence' of Pakistan but the Congress rejected it.[28] After the failure of the Cabinet Mission Plan, Jinnah called for Muslims to observe Direct Action Day to demand the creation of a separate Pakistan, which morphed into violent riots between Hindus and Muslims in Calcutta. These riots were followed by violence elsewhere, resulting in large-scale displacement in Noakhali (where Muslims attacked Hindus) and Bihar (where Hindus attacked Muslims) in October, and in Rawalpindi (where Muslims attacked and drove out Sikhs and Hindus) in March 1947.[29]

The British Prime Minister Attlee appointed Lord Louis Mountbatten as India's last viceroy, who was given the task to oversee British India's independence by June 1948, with the emphasis of preserving a United India, but with adaptational authority to ensure a British withdrawal with minimal setbacks.[30][31][32][33] British leaders including Mountbatten did not support the creation of Pakistan but failed to convince Jinnah.[34][35] Mountbatten later confessed that he would most probably have sabotaged the creation of Pakistan had he known that Jinnah was dying of tuberculosis.[36]

Soon after he arrived, Mountbatten concluded that the situation was too volatile for even that short a wait. Although his advisers favoured a gradual transfer of independence, Mountbatten decided the only way forward was a quick and orderly transfer of independence before 1947 was out. In his view, any longer would mean civil war.[37] The Viceroy also hurried so he could return to his senior technical Navy courses.[38][39] In a meeting in June, Nehru and Abul Kalam Azad representing the Congress, Jinnah representing the Muslim League, B. R. Ambedkar representing the Untouchable community, and Master Tara Singh representing the Sikhs, agreed to partition India along religious lines.

Creation of Pakistan

On 14 August 1947 (27th of Ramadan in 1366 of the Islamic Calendar) Pakistan gained independence. India gained independence the following day. Two of the provinces of British India, Punjab and Bengal, were divided along religious lines by the Radcliffe Commission. Lord Mountbatten is alleged to have influenced the Radcliffe Commission to draw the lines in India's favour.[40][41][42] Punjab's mostly Muslim western part went to Pakistan and its mostly Hindu and Sikh eastern part went to India, but there were significant Muslim minorities in Punjab's eastern section and light Hindus and Sikhs minorities living in Punjab's western areas.

There was no conception that population transfers would be necessary because of the partitioning. Religious minorities were expected to stay put in the states they found themselves residing in. However, an exception was made for Punjab which did not apply to other provinces.[43][44] Intense communal rioting in the Punjab forced the governments of India and Pakistan to agree to a forced population exchange of Muslim and Hindu/Sikh minorities living in Punjab. After this population exchange only a few thousand low-caste Hindus remained in Pakistani Punjab and only a tiny Muslim population remained in the town of Malerkotla in India's part of Punjab.[45] Political scientist Ishtiaq Ahmed says that although Muslims started the violence in Punjab, by the end of 1947 more Muslims had been killed by Hindus and Sikhs in East Punjab than the number of Hindus and Sikhs who had been killed by Muslims in West Punjab.[46][47][48] Nehru wrote to Gandhi on 22 August that up to then, twice as many Muslims had been killed in East Punjab than Hindus and Sikhs in West Punjab.[49]

More than ten million people migrated across the new borders and between 200,000 and 2,000,000[50][51][52][53] people died in the spate of communal violence in the Punjab in what some scholars have described as a 'retributive genocide' between the religions.[54] The Pakistani government claimed that 50,000 Muslim women were abducted and raped by Hindu and Sikh men and similarly the Indian government claimed that Muslims abducted and raped 33,000 Hindu and Sikh women.[55][56][57] The two governments agreed to repatriate abducted women and thousands of Hindu, Sikh and Muslim women were repatriated to their families in the 1950s. The dispute over Kashmir escalated into the first war between India and Pakistan. With the assistance of the United Nations (UN) the war was ended but it became the Kashmir dispute, unresolved as of 2023[update].

1947–1958: First democratic era

In 1947, the founding fathers of Pakistan agreed to appoint Liaquat Ali Khan as the country's first prime minister, with Muhammad Ali Jinnah as both first governor-general and speaker of the State Parliament.[58] Mountbatten had offered to serve as Governor-general of both India and Pakistan but Jinnah refused this offer.[59] When Jinnah died of tuberculosis in 1948,[60] Islamic scholar Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani described Jinnah as the greatest Muslim after the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb.

Usmani asked Pakistanis to remember Jinnah's message of "Unity, Faith and Discipline" and work to fulfil his dream:

to create a solid bloc of all Muslim states from Karachi to Ankara, from Pakistan to Morocco. He [Jinnah] wanted to see the Muslims of the world united under the banner of Islam as an effective check against the aggressive designs of their enemies.[61]

The first formal step to transform Pakistan into an ideological Islamic state was taken in March 1949 when Liaquat Ali Khan introduced the Objectives Resolution in the Constituent Assembly. The Objectives Resolution declared that sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to Allah Almighty. Support for the Objectives Resolution and the transformation of Pakistan into an Islamic state was led by Maulana Shabbir Ahmad Usmani, a respected Deobandi alim (scholar) who occupied the position of Shaykh al-Islam in Pakistan in 1949, and Maulana Mawdudi of Jamaat-i Islami.[62][63]

Indian Muslims from the United Provinces, Bombay Province, Central Provinces and other areas of India continued migrating to Pakistan throughout the 1950 and 1960s and settled mainly in urban Sindh, particularly in the new country's first capital, Karachi.[45] Prime Minister Ali Khan established a strong government and had to face challenges soon after gaining the office.[58] His Finance Secretary Victor Turner announced the country's first monetary policy by establishing the State Bank, the Federal Bureau of Statistics and the Federal Board of Revenue to improve statistical knowledge, finance, taxation, and revenue collection in the country.[64] There were also problems because India cut off water supply to Pakistan from two canal headworks in its side of Punjab on 1 April 1948 and also withheld delivering Pakistan its share of the assets and funds of United India, which the Indian government released after Gandhi's pressurisation.[65] Territorial problems arose with neighbouring Afghanistan over the Pakistan–Afghanistan border in 1949, and with India over the Line of Control in Kashmir.[58] Diplomatic recognition became a problem when the Soviet Union led by Joseph Stalin did not welcome the partition which established Pakistan and India. Imperial State of Iran was the first country to recognise Pakistan in 1947.[66] In 1948, Ben-Gurion of Israel sent a secret courier to Jinnah to establish the diplomatic relations, but Jinnah did not give any response to Ben-Gurion.

After gaining Independence, Pakistan vigorously pursued bilateral relations with other Muslim countries[67] and made a wholehearted bid for leadership of the Muslim world, or at least for leadership in achieving its unity.[68] The Ali brothers had sought to project Pakistan as the natural leader of the Islamic world, in large part due to its large population and military strength.[69] A top ranking Muslim League leader, Khaliquzzaman, declared that Pakistan would bring together all Muslim countries into Islamistan – a pan-Islamic entity.[70] The USA, which did not approve of Pakistan's creation, was against this idea and British Prime Minister Clement Attlee voiced international opinion at the time by stating that he wished that India and Pakistan would re-unite, fearing unity of the Muslim World.[71] Since most of the Arab world was undergoing a nationalist awakening at the time, there was little attraction in Pakistan's pan-Islamic aspirations.[72] Some of the Arab countries saw the 'Islamistan' project as a Pakistani attempt to dominate other Muslim states.[73] Pakistan vigorously championed the right of self-determination for Muslims around the world. Pakistan's efforts for the independence movements of Indonesia, Algeria, Tunisia, Morocco and Eritrea were significant and initially led to close ties between these countries and Pakistan.[74]

In a 1948 speech, Jinnah declared that "Urdu alone would be the state language and the lingua franca of the Pakistan state", although at the same time he called for the Bengali language to be the official language of the Bengal province.[75] Nonetheless, tensions began to grow in East Bengal.[75] Jinnah's health further deteriorated and he died in 1948. Bengali leader, Sir Khawaja Nazimuddin succeeded as the governor general of Pakistan.[76]

During a massive political rally in 1951, Prime Minister Ali Khan was assassinated, and Nazimuddin became the second prime minister.[58] Tensions in East Pakistan reached a climax in 1952, when the East Pakistani police opened fire on students protesting for the Bengali language to receive equal status with Urdu. The situation was controlled by Nazimuddin who issued a waiver granting the Bengali language equal status, a right codified in the 1956 constitution. In 1953 at the instigation of religious parties, anti-Ahmadiyya riots erupted, which led to many Ahmadi deaths.[77] The riots were investigated by a two-member court of inquiry in 1954,[78] which was criticised by the Jamaat-e-Islami, one of the parties accused of inciting the riots.[79] This event led to the first instance of martial law in the country and began the history of military intervention into the politics and civilian affairs of the country.[80] In 1954 the controversial One Unit Program was imposed by the last Pakistan Muslim League (PML) Prime minister Ali Bogra dividing Pakistan on the German geopolitical model.[81] The same year the first legislative elections were held in Pakistan, which saw the communists gaining control of East Pakistan.[82] The 1954 election results clarified the differences in ideology between West and East Pakistan, with East Pakistan under the influence of the Communist Party allying with the Shramik Krishak Samajbadi Dal (Workers Party) and the Awami League.[82] The pro-American Republican Party gained a majority in West Pakistan, ousting the PML government.[82] After a vote of confidence in Parliament and the promulgation of the 1956 constitution, which confirmed Pakistan as an Islamic republic, two notable figures became prime minister and president, as the first Bengali leaders of the country. Huseyn Suhrawardy became the prime minister leading a communist-socialist alliance, and Iskander Mirza became the first president of Pakistan.[83]

Suhrawardy's foreign policy was directed towards improving the fractured relations with the Soviet Union and strengthening relations with the United States and China after paying first a state visit to each country.[84] Announcing a new self-reliance program, Suhrawardy began building a massive military and launched a nuclear power program in the west in an attempt to legitimise his mandate in West Pakistan.[85] Suhrawardy's efforts led to an American training program for the country's armed forces which met with great opposition in East Pakistan. His party in the East Pakistan Parliament threatened to leave the state of Pakistan. Suhrawardy also verbally authorised the leasing the Inter-Services Intelligence's (ISI) secret installation at Peshawar Air Station to the CIA to conduct operations in the Soviet Union.[85]

Differences in East Pakistan further encouraged Baloch separatism, and in an attempt to intimidate the communists in East Pakistan President Mirza initiated massive arrests of communists and party workers of the Awami League, which damaged the image of West Pakistan in the east.[85] The western contingent's lawmakers determinately followed the idea of a westernised Parliamentary form of democracy, while East Pakistan opted for becoming a socialist state. The One Unit Program and the centralisation of the national economy on the Soviet model was met with great hostility and resistance in West Pakistan. The eastern contingent's economy was rapidly centralised by Suhrawardy's government.[84] Personal problems grew between the two Bengali leaders, further damaging the unity of the country and causing Suhrawardy to lose his authority in his own party to the growing influence of cleric Maulana Bhashani.[84] Resigning under a threat of dismissal by Mirza, Suhrawardy was succeeded by I. I. Chundrigar in 1957.[84] Within two months Chundrigar was dismissed. He was followed by Sir Feroz Noon, who proved to be an incapable prime minister. Public support for the Muslim League led by Nurul Amin began to threaten President Mirza who was becoming unpopular, especially in West Pakistan.[82] In less than two years, Mirza dismissed four elected prime ministers, and was increasingly under pressure to call new elections in 1958.[86]

1958–1971: first military era

1958: military rule

In October 1958 President Iskandar Mirza issued orders for a massive mobilisation of the Pakistan Armed Forces and appointed Chief of Army Staff General Ayub Khan as Commander-in-chief.[87] President Mirza declared a state of emergency, imposed martial law, suspended the constitution, and dissolved both the socialist government in East Pakistan and the parliamentary government in West Pakistan.[88]

General Ayub Khan was Chief Martial Law Administrator, with authority throughout the country.[87] Within two weeks President Mirza attempted to dismiss Khan,[87] but the move backfired and President Mirza was relieved of the presidency and exiled to London. General Khan promoted himself to the rank of a five-star field marshal and assumed the presidency. He was succeeded as chief of army staff by General Muhammad Musa. Khan named a new civil-military government under him.[89][90]

1962–1969: presidential republic

The parliamentary system came to an end in 1958, following the imposition of martial law.[91] Tales of corruption in the civil bureaucracy and public administration had maligned the democratic process in the country and the public were supportive of the actions taken by General Khan.[91] Major land reforms were carried out by the military government and it enforced the controversial Elective Bodies Disqualification Order which ultimately disqualified H. S. Suhrawardy from holding public office.[91] Khan introduced a new presidential system called "Basic Democracy", by which an electoral college of 80,000 would select the president.[89] He also promulgated the 1962 constitution.[89] In a national referendum held in 1960 Ayub Khan secured nationwide popular support for his bid as second president of Pakistan and replaced his military regime with a constitutional civilian government.[91] In a major development all of the infrastructure and bureaucracy of the capital was relocated from Karachi to Islamabad.[92]

The presidency of Ayub Khan is often celebrated as the "Great Decade", highlighting the economic development plans and reforms executed.[92] Under Ayub's presidency the country underwent a cultural shift when the pop music industry, the film industry and Pakistani drama became extremely popular during the 1960s. Rather than preferring neutrality, Ayub Khan worked closely to form an alliance with the United States and the western world. Pakistan joined two formal military alliances opposed to the Soviet bloc: the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) in 1955;[93] and the Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) in 1962.[94] During this period the private sector gained more power and educational reforms, human development and scientific achievements gained international recognition.[92] In 1961 the Pakistani space program was launched and the nuclear power program was continued. Military aid from the US grew, but the country's national security was severely compromised following the exposure of U2 secret spy operations launching from Peshawar to overfly the Soviet Union in 1960. The same year Pakistan signed the Indus Waters Treaty with India in an attempt to normalise relations.[95] Relations with China strengthened after the Sino-Indian War, with a boundary agreement being signed in 1963; this shifted the balance of the Cold War by bringing Pakistan and China closer together while loosening ties between Pakistan and the United States.[96] In 1964 the Pakistani Armed Forces quelled a suspected pro-communist revolt in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, West Pakistan, allegedly supported by communist Afghanistan.[clarification needed] During the controversial 1965 presidential elections, Ayub Khan almost lost to Fatima Jinnah.[97]

In 1965, after Pakistan went ahead with its strategic infiltration mission in Kashmir codenamed Operation Gibraltar, India declared full-scale war against Pakistan.[98] The war, which ended militarily in a stalemate, was mostly fought in the west.[99] Controversially, the East Pakistani Army did not interfere in the conflict and this caused anger in West Pakistan against East Pakistan.[100] The war with India was met with disfavor by the United States, which dismayed Pakistan by adopting a policy of denying military aid to both India and Pakistan.[101] Positive diplomatic gains were made via several treaties strengthening Pakistan's historical bonds with its western neighbours in Asia. A successful intervention by the USSR led to the signing of the Tashkent Agreement between India and Pakistan in 1965.[102] Witnessing the American disapproval and the USSR's mediation, Ayub Khan made tremendous efforts to normalise relations with the USSR; Bhutto's negotiating expertise led to the Soviet Premier, Alexei Kosygin, visiting Islamabad.[98]

Delivering a blistering speech at the UN General Assembly in 1965, Foreign Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, with the atomic scientist Aziz Ahmed present, made Pakistan's intentions clear and announced that: "If India builds the [nuclear] bomb, we will eat grass, even go hungry, but we will get one of [our] own... We have no other choice". Abdus Salam and Munir Khan jointly collaborated to expand the nuclear power infrastructure, receiving tremendous support from Bhutto. Following the announcement, the nuclear power expansion was accelerated with the signing of a commercial nuclear power plant agreement with General Electric Canada, and several other agreements with the United Kingdom and France.

Disagreeing with the signing of Tashkent agreement, Bhutto was ousted from the ministry on the personal directive of President Khan in 1966.[103] The dismissal of Bhutto caused spontaneous mass demonstrations and public anger against Khan, leading to major industrial and labour strikes in the country.[104] Within weeks Ayub Khan lost the momentum in West Pakistan and his image was damaged in public circles.[102] In 1968, Ayub Khan decided to celebrate his "Decade of Development," it was strongly condemned by leftist students and they decided to celebrate, instead, a "Decade of Decadence.[105] Leftists accused him of encouraging crony capitalism, the exploitation of workers and the suppression of the rights and ethnic-nationalism of the Bengalis (in East Pakistan), Sindhis, the Baloch and the Pakhtun.[106] Amidst further allegations that economic development and hiring for government jobs favoured West Pakistan, Bengali nationalism began to increase and an independence movement gained ground in East Pakistan.[107] In 1966 the Awami League led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman demanded provisional autonomy at the Round Table Conference held by Ayub Khan; this was forcefully rejected by Bhutto.[107] The influence of socialism increased after the country's notable economist, Mahbub ul Haq, publishing a report on the private-sector's evasion of taxation and the control of the national economy by a few oligarchs.[108] In 1967 a Socialist convention, attended by the country's leftist philosophers and notable thinkers, took place in Lahore. The Pakistan People's Party (PPP) was founded with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto as its first elected chairman. The Peoples Party's leaders, JA Rahim and Mubashir Hassan, notably announced their intention to "defeat the great dictator with the power of the people."[104]

In 1967, the PPP tapped a wave of anger against Ayub Khan and successfully called for major labour strikes in the country.[104] Despite severe repression, in what is known as the 1968 movement in Pakistan, people belonging to different occupations revolted against the regime.[109] Criticism from the United States further damaged Ayub Khan's authority in the country.[104] By the end of 1968, Khan presented the Agartala Case which led to the arrests of many Awami League leaders, but was forced to withdraw it after a serious uprising in East Pakistan. Under pressure from the PPP, public resentment, and anger against his administration, Khan resigned from the presidency in poor health and handed over his authority to the army commander, a little known personality and heavy alcoholic, General Yahya Khan, who imposed martial law.

1969–1971: Martial law

President General Yahya Khan was aware of the explosive political situation in the country.[104] Support for progressive and socialist groups was rising, and calls for a change of regime were gaining momentum.[104] In a television address to the nation, President Khan announced his intention to hold nationwide elections the following year and to transfer power to the elected representatives.[104] Virtually suspending the 1962 Constitution, President Khan instead issued the Legal Framework Order No. 1970 (LFO No. 1970) which caused radical changes in West Pakistan. Tightening the grip of martial law, the One Unit program was dissolved in West Pakistan, removing the "West" prefix from Pakistan, and a direct ballot replaced the principle of parity.[110] Territorial changes were carried out in four of the country's provinces, allowing them to retain their geographical structures as they were in 1947.[110] The state parliament, supreme court, major government, and authoritarian institutions also regained their statuses.[110] This decree was limited to West Pakistan, it had no effect on East Pakistan.[110] Civilians in Ayub Khan's administration were dismissed by the military government which replaced them with military officers.

The Election Commission registered 24 political parties, and public meetings attracted many large crowds. On the eve of the elections, a cyclone struck East Pakistan killing approximately 500,000 people, though this event did not deter people from participating in the first ever general election.[111] Mobilizing support for their Six Points manifesto the Awami League secured electoral support in East Pakistan.[111] Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto's Pakistan Peoples Party asserted itself even more. Its socialist rationale, roti kapda aur makaan (food, cloth, and shelter) and the party's socialist manifesto quickly popularised the party.[111] The conservative PML, led by Nurul Amin, raised religious and nationalist slogans all over the country.[111]

Out of a total of 313 seats in the National Assembly, the Awami League won 167 seats but none from West Pakistan[111] and the PPP won 88 seats but none from East Pakistan. While the Awami League had won enough seats to form a government without the need for any coalition, West Pakistani elites refused to hand over power to the East Pakistani party. Efforts were made to start a constitutional dialogue. Bhutto asked for a share in government saying Udhar tum, idhar hum, meaning "You in the east, I in the west". The PPP's intellectuals maintained that the Awami League had no mandate in West Pakistan.[112] Although President Khan invited the Awami League to a National Assembly session in Islamabad he did not ask them to form a government, due to opposition from the PPP.[112] When no agreement was reached, President Khan appointed Bengali anti-war activist Nurul Amin as prime minister with the additional office of the country's first and only vice-president.[112]

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman then launched a non-cooperation movement which effectively paralysed the state machinery in East Pakistan. Talks between Bhutto and Rehman collapsed and President Khan ordered armed action against the Awami League. Operations Searchlight and Barisal led to a crackdown on East Pakistani politicians, civilians, and student activists. Sheikh Rahman was arrested and extradited to Islamabad, while the entire Awami League leadership escaped to India to set up a parallel government. A guerrilla insurgency was initiated by the Indian-organised and supported Mukti Bahini ("freedom fighters").[113] Millions of Bengali Hindus and Muslims took refuge in eastern India leading to Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi announcing support for the Bangladesh liberation war and providing direct military assistance to the Bengalis.[114] In March 1971 regional commander Major General Ziaur Rahman declared the independence of East Pakistan as the new nation of Bangladesh on behalf of Mujib.

Pakistan launched pre-emptive air strikes on 11 Indian airbases on 3 December 1971, leading to India's entry into the war on the side of Bangladeshi nationalist forces. Untrained in guerrilla warfare, the Pakistani high command in the east collapsed under commanders General Amir Niazi and Admiral Muhammad Sharif.[112] Exhausted, outflanked and overwhelmed, they could no longer continue the fight against the intense guerrilla insurgency, and finally surrendered to the Allied Forces of Bangladesh and India in Dhaka on 16 December 1971.[112] Nearly 90,000 Pakistani soldiers were taken prisoners of war and the result was the emergence of the new nation of Bangladesh,[115] thus ending 24 years of turbulent union between the two wings.[112] However, according to Indian Army Chief Sam Manekshaw the Pakistani Army had fought gallantly.[116] Independent researchers estimate that between 300,000 and 500,000 civilians died during this period while the Bangladesh government puts the number of dead at three million,[117]//Amazing Facts (Excited Facts) a figure that is now nearly universally regarded as excessively inflated.[118] Some academics such as Rudolph Rummel and Rounaq Jahan say both sides[119] committed genocide; others such as Richard Sisson and Leo E. Rose believe there was no genocide.[120] Discredited by the defeat, President Khan resigned and Bhutto was inaugurated as president and chief martial law administrator on 20 December 1971.[112]

1971–1977: Second democratic era

The 1971 war and the separation of East Pakistan demoralised the nation. With the PPP's assumption of power, democratic socialists and visionaries had authority for the first time in the country's history. Bhutto dismissed the chiefs of the army, navy and the air force and ordered house arrest for General Yahya Khan and several of his collaborators. He adopted the Hamoodur Rahman Commission's recommendations and authorised large-scale courts-martial of army officers tainted by their role in East Pakistan. To keep the country united Bhutto launched a series of internal intelligence operations to crack down on fissiparous nationalist sentiments and movements in the provinces.

1971 to 1977 was a period of left-wing democracy and the growth of economic nationalisation, covert atomic bomb projects, promotion of science, literature, cultural activities and Pakistani nationalism. In 1972 the country's top intelligence services provided an assessment on the Indian nuclear program, concluding that: "India was close to developing a nuclear weapon under its nuclear programme". Chairing a secret seminar in January 1972, which came to be known as "Multan meeting", Bhutto rallied Pakistani scientists to build an atomic bomb for national survival. The atomic bomb project brought together a team of prominent academic scientists and engineers, headed by theoretical physicist Abdus Salam. Salam later won the Nobel Prize in Physics for developing the theory for the unification of the weak nuclear and electromagnetic forces.[121]

The PPP created the 1973 Constitution with the support of Islamists.[122] The Constitution declared Pakistan an Islamic Republic and Islam the state religion. It also stated that all laws would have to be brought into accordance with the injunctions of Islam as laid down in the Quran and Sunnah and that no law repugnant to such injunctions could be enacted.[123] The 1973 Constitution also created institutions such as the Shariat Court and the Council of Islamic Ideology to channel and interpret the application of Islam to the law.[124]

In 1973 a serious nationalist rebellion took place in Balochistan province, which was harshly suppressed; the Shah of Iran purportedly assisted with air support in order to prevent the conflict from spilling over into Iranian Balochistan. Bhutto's government carried out major reforms such as the re-designing of the country's infrastructure, the establishment of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee and the reorganisation of the military. Steps were taken to encourage the expansion of the country's economic and human infrastructure, starting with the agriculture, land reforms, industrialisation and the expansion of the higher education system throughout the country. Bhutto's efforts undermined and dismantled the private-sector and conservative approach to political power in the country's political setup. In 1974 Bhutto succumbed to increasing pressure from religious parties and encouraged Parliament to declare adherents of Ahmadiyya to be non-Muslims.

Relations with the United States deteriorated as Pakistan normalised relations with the Soviet Union, the Eastern Bloc, North Korea, China, and the Arab world. With Soviet technical assistance the country's first steel mill was established in Karachi, which proved to be a crucial step in industrialising the economy. Alarmed by India's surprise nuclear test in 1974, Bhutto accelerated Pakistan's atomic bomb project.[125] This crash project led to a secret sub-critical testings, Kirana-I and Test Kahuta, in 1983. Relations with India soured and Bhutto sponsored aggressive measures against India at the United Nations. These openly targeted the Indian nuclear programme.

From 1976 to 1977, Bhutto was in diplomatic conflict with the United States, which worked covertly to damage the credibility of Bhutto in Pakistan. Bhutto, with his scientist colleague Aziz Ahmed, thwarted US attempts to infiltrate the atomic bomb programme. In 1976, during a secret mission, Henry Kissinger threatened Bhutto and his colleagues. In response Bhutto aggressively campaigned for efforts to speed up the atomic project.

In early 1976 Bhutto's socialist alliance collapsed, forcing his left-wing allies to form an alliance with right-wing conservatives and Islamists to challenge the power of the PPP. The Islamists started a Nizam-e-Mustafa movement[126] which demanded the establishment of an Islamic state in the country and the removal of immorality from society. In an effort to meet the demands of Islamists Bhutto banned the drinking and selling of wine by Muslims, nightclubs and horse racing.[127] In 1977 general elections were held in which the Peoples Party were victorious. This was challenged by the opposition, which accused Bhutto of rigging the election process. There were protests against Bhutto and public disorder, causing Chief of the Army Staff General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq to take power in a bloodless coup. Following this Bhutto and his leftist colleagues were dragged into a two-year-long political trial in the Supreme Court. Bhutto was executed in 1979 after being convicted of authorising the murder of a political opponent in a controversial 4–3 split decision by the Supreme Court.

1977–1988: Second military era

This period of military rule, lasting from 1977 to 1988, is often regarded as a period of persecution and the growth of state-sponsored religious conservatism. Zia-ul-Haq committed himself to establishing an Islamic state and enforcing sharia law.[127] He established separate shariat judicial courts[128] and court benches[129][130] to judge legal cases using Islamic doctrine.[131] New criminal offences of adultery, fornication and types of blasphemy, and new punishments of whipping, amputation, and stoning to death, were added to Pakistani law. Interest payments for bank accounts were replaced by "profit and loss" payments. Zakat charitable donations became a 2.5% annual tax. School textbooks and libraries were overhauled to remove un-Islamic material.[132] Offices, schools and factories were required to offer prayer space.[133] Zia bolstered the influence of the Islamic clergy and the Islamic parties,[131] whilst conservative scholars became fixtures on television.[133] Thousands of activists from the Jamaat-e-Islami party were appointed to government posts to ensure the continuation of his agenda after his death.[127][131][134][135] Conservative Islamic scholars were appointed to the Council of Islamic Ideology.[129] Separate electorates for Hindus and Christians were established in 1985 even though Christian and Hindu leaders complained that they felt excluded from the county's political process.[136] Zia's state-sponsored Islamization increased sectarian divisions in Pakistan between Sunnis and Shias due to his anti-Shia policies[137] and also between Deobandis and Barelvis.[138] Zia-ul-Haq forged a strong alliance between the military and Deobandi institutions.[139] Possible motivations for the Islamization programme included Zia's personal piety (most accounts agree that he came from a religious family),[140] his desire to gain political allies, to "fulfill Pakistan's raison d'être" as a Muslim state, or the political need to legitimise what was seen by some Pakistanis as his "repressive, un-representative martial law regime".[141]

President Zia's long eleven-year rule featured the country's first successful technocracy. It also featured the tug of war between far-leftist forces in direct competition with populist far-right circles. President Zia installed many high-profile military officers in civilian posts, ranging from central to provisional governments. Gradually the influence of socialism in public policies was dismantled. Instead a new system of capitalism was revived with the introduction of corporatisation and the Islamization of the economy. The populist movement against Bhutto scattered, with far right-wing conservatives allying with General Zia's government and encouraging the military government to crack down on pro-Soviet left-wing elements. The left-wing alliance, led by Benazir Bhutto, was brutalised by Zia who took aggressive measures against the movement. Further secessionist uprisings in Balochistan were put down successfully by the provincial governor, General Rahimuddin Khan. In 1984, Zia held a referendum asking for support for his religious programme; he received overwhelming support.

After Zia assumed power, Pakistan's relations with the Soviet Union deteriorated and Zia strove for strong relations with the United States. After the Soviet Union's intervention in Afghanistan President Ronald Reagan immediately moved to help Zia supply and finance an anti-Soviet insurgency. Zia's military administration effectively handled national security matters and managed multibillion-dollars of aid from the United States. Millions of Afghan refugees poured into the country, fleeing the Soviet occupation and atrocities. Some estimate that the Soviet troops killed up to 2 million Afghans[142] and raped many Afghan women.[143] It was the largest refugee population in the world at the time,[144] which had a heavy impact on Pakistan. Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province became a base for the anti-Soviet Afghan fighters, with the province's influential Deobandi ulama playing a significant role in encouraging and organising the jihad against the Soviet forces.[145] In retaliation the Afghan secret police carried out a large number of terrorist operations against Pakistan, which also suffered from an influx of illegal weapons and drugs from Afghanistan. Responding to the terrorism, Zia used "counter-terrorism" tactics and allowed the religiously far-right parties to send thousands of young students from clerical schools to participate in the Afghan jihad against the Soviet Union.

Problems with India arose when India attacked and took the Siachen glacier, prompting Pakistan to strike back. This led the Indian Army to carry out a military exercise which mustered up to 400,000 troops near southern Pakistan. Facing an indirect war with the Soviet Union in the west, General Zia used cricket diplomacy to lessen the tensions with India. He also reportedly threatened India by saying to Rajiv Gandhi "If your forces cross our border an inch... We are going to annihilate your (cities)...".[146]

Under pressure from President Reagan, General Zia finally lifted martial law in 1985, holding non-partisan elections and handpicking Muhammad Khan Junejo to be the new prime minister. Junejo in turn extended Zia's term as Chief of Army Staff until 1990. Junejo gradually fell out with Zia as his administrative independence grew; for instance, Junejo signed the Geneva Accord, which Zia disapproved of. A controversy loomed after a large-scale blast at a munitions dump, with Prime minister Junejo vowing to bring to justice those responsible for the significant damage caused and implicating several senior generals. In return General Zia dismissed the Junejo government on several charges in May 1988 and called for elections in November 1988. Before the elections could take place General Zia died in a mysterious plane crash on 17 August 1988. According to Shajeel Zaidi a million people attended Zia ul Haq's funeral because he had given them what they wanted: more religion.[147] A PEW opinion poll found that 84% of Pakistanis favoured making sharia the law of the land.[148] Conversely, towards the end of Zia's regime, there was a popular wave of cultural change in the country.[149] Despite Zia's tough rhetoric against the Western culture and music, underground rock music jolted the country and revived the cultural counter-attack on the Indian film industry.[149]

1988–1999: Third democratic era (Benazir–Nawaz)

Democracy returned again in 1988 with general elections which were held after President Zia-ul-Haq's death. The elections marked the return of the Peoples Party to power. Their leader, Benazir Bhutto, became the first female prime minister of Pakistan as well as the first female head of government in a Muslim-majority country. This period, lasting until 1999, introduced competitive two-party democracy to the country. It featured a fierce competition between centre-right conservatives led by Nawaz Sharif and centre-left socialists led by Benazir Bhutto. The far-left and the far-right disappeared from the political arena with the fall of global communism and the United States lessening its interests in Pakistan.

Prime Minister Bhutto presided over the country during the penultimate period of the Cold war, and cemented pro-Western policies due to a common distrust of communism. Her government observed the troop evacuation of the Soviet Union from neighbouring Afghanistan. Soon after the evacuation the alliance with the US came to an end when Pakistan's atomic bomb project was revealed to the world, leading to the imposition of economic sanctions by the United States. In 1989, Bhutto ordered a military intervention in Afghanistan, which failed, leading her to dismiss the directors of the intelligence services. With US aid she imposed the Seventh Five-Year Plan to restore and centralise the national economy. Nonetheless, the economic situation worsened when the state currency lost a currency war with India. The country entered a period of stagflation, and her government was dismissed by the conservative president, Ghulam Ishaq Khan.

The 1990 general election results allowed the right-wing conservative alliance the Islamic Democratic Alliance (IDA) led by Nawaz Sharif to form a government under a democratic system for the first time. Attempting to end stagflation Sharif launched a program of privatisation and economic liberalisation. His government adopted a policy of ambiguity regarding atomic bomb programs. Sharif intervened in the Gulf War in 1991, and ordered an operation against the liberal forces in Karachi in 1992. Institutional problems arose with president Ishaq, who attempted to dismiss Sharif on the same charges he had used against Benazir Bhutto. Through a Supreme Court judgement Sharif was restored and together with Bhutto ousted Khan from the presidency. Weeks later Sharif was forced to relinquish office by the military leadership.

As a result of the 1993 general elections Benazir Bhutto secured a plurality and formed a government after hand-picking a president. She approved the appointments of all four four-star chiefs of staff: Mansurul Haq of the navy; Abbas Khattak of the air force; Abdul Waheed of the army; and Farooq Feroze Khan chairman of the joint chiefs. She oversaw a tough stance to bring political stability, which, with her fiery rhetoric, earned her the nickname "Iron Lady" from her rivals. Proponents of social democracy and national pride were supported, while the nationalisation and centralisation of the economy continued after the Eighth Five-Year Plan was enacted to end stagflation. Her foreign policy made an effort to balance relations with Iran, the United States, the European Union and the socialist states.

Pakistan's intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), became involved in supporting Muslims around the world. ISI's Director-General Javed Nasir later confessed that despite the UN arms embargo on Bosnia the ISI airlifted anti-tank weapons and missiles to the Bosnian mujahideen which turned the tide in favour of Bosnian Muslims and forced the Serbs to lift the siege of Sarajevo.[150][151][152] Under Nasir's leadership the ISI was also involved in supporting Chinese Muslims in Xinjiang Province, rebel Muslim groups in the Philippines, and some religious groups in Central Asia.[151] Pakistan was one of only three countries which recognised the Taliban government and Mullah Mohammed Omar as the legitimate ruler of Afghanistan.[153] Benazir Bhutto continued her pressure on India, pushing India on to take defensive positions on its nuclear programme. Bhutto's clandestine initiatives modernised and expanded the atomic bomb programme after initiating missile system programs. In 1994 she successfully approached France for the transfer of Air-independent propulsion technology.

Focusing on cultural development, her policies resulted in growth in the rock and pop music industry, and the film industry made a comeback after introducing new talent. She exercised tough policies to ban Indian media in the country, while promoting the television industry to produce dramas, films, artistic programs and music. Public anxiety about the weakness of Pakistani education led to large-scale federal support for science education and research by both Bhutto and Sharif. Despite her tough policies, the popularity of Benazir Bhutto waned after her husband allegedly became involved in the controversial death of Murtaza Bhutto. Many public figures and officials suspected Benazir Bhutto's involvement in the murder, although there was no proof. In 1996, seven weeks after this incident, Benazir Bhutto's government was dismissed by her own hand-picked president on charges of Murtaza Bhutto's death.

The 1997 election resulted in conservatives receiving a large majority of the vote and winning enough seats in parliament to change the constitution to eliminate the checks and balances that restrained the prime minister's power. Institutional challenges to authority of the new prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, were led by the civilian President Farooq Leghari, Chairman Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee General Jehangir Karamat, Chief of Naval Staff Admiral Fasih Bokharie, and Chief Justice Sajjad Ali Shah. These were countered and all four were forced to resign, Chief Justice Shah doing so after the Supreme Court was stormed by Sharif partisans.[154]

Problems with India further escalated in 1998, when television reported Indian nuclear explosions, codenamed Operation Shakti. When this news reached Pakistan, a shocked Sharif called a Defence Committee of the Cabinet meeting in Islamabad and vowed that "she [Pakistan] would give a suitable reply to the Indians...". After reviewing the effects of the tests for roughly two weeks Sharif ordered the Pakistan Atomic Energy Commission to perform a series of nuclear tests in the remote area of the Chagai Hills. The military forces in the country were mobilised at war-readiness on the Indian border.

Internationally condemned, but extremely popular at home, Sharif took steps to control the economy. Sharif responded fiercely to international criticism and defused the pressure by attacking India for nuclear proliferation and the US for the atomic bombing of Japan:

The World, instead of putting pressure on [India]... not to take the destructive road... imposed all kinds of sanctions on [Pakistan] for no fault of her...! If Japan had its own nuclear capability...[the cities of]...Hiroshima and Nagasaki would not have suffered atomic destruction at the hands of the... United States

Under Sharif's leadership, Pakistan became the seventh declared nuclear-weapon state, the first in the Muslim world. The conservative government also adopted environmental policies after establishing the Pakistan Environmental Protection Agency. Sharif continued Bhutto's cultural policies, though he did allow access to Indian media.

The next year the Kargil war, by Pakistan-backed Kashmiri militants, threatened to escalate to a full-scale war[156] and increased fears of a nuclear war in South Asia. Internationally condemned, the Kargil war was followed by the Atlantique Incident, which came on a bad juncture for the Prime minister Sharif who no longer had broad public support for his government.

On 12 October 1999 Prime Minister Sharif's attempt to dismiss General Pervez Musharraf from the posts of Chairman of the Joint Chiefs and Chief of Army Staff failed after the military leadership refused to accept the appointment of ISI Director Lieutenant-General Ziauddin Butt his replacement.[157] Sharif ordered Jinnah International Airport to be sealed to prevent the landing of a PIA flight carrying General Musharraf, which then circled the skies over Karachi for several hours. A counter coup was initiated and the senior commanders of the military leadership ousted Sharif's government and took over the airport. The flight landed with only a few minutes of fuel to spare.[158] The Military Police seized the Prime Minister's Secretariat and deposed Sharif, Ziauddin Butt and the cabinet staffers who took part in this assumed conspiracy, placing them in the infamous Adiala Jail. A quick trial was held in the Supreme Court which gave Sharif a life sentence, with his assets being frozen based on a corruption scandal. He came close to receiving the death sentence based on the hijacking case.[159] The news of Sharif's dismissal made headlines all over the world and under pressure from US President Bill Clinton and King Fahd of Saudi Arabia Musharraf agreed to spare Sharif's life. Exiled to Saudi Arabia, Sharif was forced to be out of politics for nearly ten years.

1999–2007: Third military era (Musharraf–Aziz)

The presidency of Musharraf featured the arrival of liberal forces in national power for the first time in the history of Pakistan.[160] Early initiatives were taken towards the continuation of economic liberalisation, privatisation and freedom of the media in 1999.[161] The Citibank executive, Shaukat Aziz, returned to the country to take control of the economy.[162] In 2000 the government issued a nationwide amnesty to the political workers of liberal parties, sidelining the conservatives and leftists in the country.[163][164] Intending the policy to create a counter-cultural attack on India, Musharraf personally signed and issued hundreds of licenses to the private sector to open new media outlets, free from government influence. On 12 May 2000 the Supreme Court ordered the Government to hold general elections by 12 October 2002. Ties with the United States were renewed by Musharraf who endorsed the American invasion of Afghanistan in 2001.[165] Confrontation with India continued over Kashmir, which led to a serious military standoff in 2002 after India alleged Pakistan-backed Kashmiri insurgents carried out the 2001 Indian Parliament attack.[166]

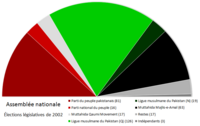

Attempting to legitimise his presidency[167] Musharraf held a controversial referendum in 2002,[168] which allowed the extension of his presidential term to five years.[169] The LFO Order No. 2002 was issued by Musharraf in August 2001, which established the constitutional basis for his continuance in office.[170] The 2002 general elections resulted in the liberals, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), the Third Way centrists and the Pakistan Muslim League (Q), winning the majority in parliament and forming a government. Disagreement over Musharraf's attempt to extend his term effectively paralysed parliament for over a year. The Musharraf-backed liberals eventually mustered the two-thirds majority required to pass the 17th Amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan. This retroactively legitimised Musharraf's 1999 actions and many of his subsequent decrees as well as extending his term as president. In a vote of confidence in January 2004, Musharraf won 658 out of 1,170 votes in the electoral college, and was elected president.[171] Soon after Musharraf increased the role of Shaukat Aziz in parliament and helped him to secure nomination for the office of Prime Minister.

Shaukat Aziz became prime minister in 2004. His government achieved positive results on the economic front, but his proposed social reforms were met with resistance. The far-right Muttahida Majlis-e-Amal mobilised in fierce opposition to Musharraf and Aziz and their support for the US intervention in Afghanistan.[172][173] Over two years Musharraf and Aziz survived several assassination attempts by al-Qaeda, including at least two where they had inside information from a member of the military.[163] On foreign fronts allegations of nuclear proliferation damaged Musharraf and Aziz's credibility. Repression and subjugation in tribal areas of Pakistan led to heavy fighting in Warsk with 400 al-Qaeda operatives in March 2004. This new conflict caused the government to sign a truce with the Taliban on 5 September 2006 but sectarian violence continued.

In 2007 Sharif made a daring attempt to return from exile but was refrained from landing at Islamabad Airport.[174] This did not deter another former prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, from returning on 18 October 2007 after an eight-year exile in Dubai and London to prepare for the 2008 parliamentary elections.[175][176] While leading a massive rally of supporters, two suicide attacks were carried out in an attempt to assassinate her. She escaped unharmed but there were 136 dead and at least 450 people were injured.[177]

With Aziz completing his term, the liberal alliance now led by Musharraf was further weakened after General Musharraf proclaimed a state of emergency and sacked the Chief Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry along with the other 14 judges of the Supreme Court, on 3 November 2007.[160][178][179] The political situation became more chaotic when lawyers launched a protest against this action and were arrested. All private media channels including foreign channels were banned.[180] Domestic crime and violence increased while Musharraf attempted to contain the political pressure. Stepping down from the military, he was sworn in for a second presidential term on 28 November 2007.[181][182]

Popular support for Musharraf declined when Nawaz Sharif successfully made a second attempt to return from exile, this time accompanied by his younger brother and his daughter. Hundreds of their supporters were detained before the pair arrived at Iqbal Terminal on 25 November 2007.[183][184] Nawaz Sharif filed his nomination papers for two seats in the forthcoming elections whilst Benazir Bhutto filed for three seats including one of the reserved seats for women.[185] Departing an election rally in Rawalpindi on 27 December 2007, Benazir Bhutto was assassinated by a gunman who shot her in the neck and set off a bomb.[186][187][188] The exact sequence of the events and cause of death became points of political debate and controversy. Early reports indicated that Bhutto was hit by shrapnel or gunshots,[189] but the Pakistani Interior ministry maintained that her death was due from a skull fracture sustained when the explosive waves threw her against the sunroof of her vehicle.[190] The issue remains controversial and further investigations were conducted by the UK police. The Election Commission announced that due to the assassination[191] the elections, which had been scheduled for 8 January 2008, would take place on 18 February.[192]

The 2008 general elections marked the return of the leftists.[193][194] The left oriented PPP and conservative PML, won a majority of the seats and formed a coalition government; the liberal alliance had faded. Yousaf Raza Gillani of the PPP became Prime Minister and consolidated his power after ending a policy deadlock in order to lead the movement to impeach the president on 7 August 2008. Before restoring the deposed judiciary, Gillani and his leftist alliance leveled accusations against Musharraf of weakening Pakistan's unity, violating its constitution and creating an economic impasse.[195] Gillani's strategy succeeded when Pervez Musharraf announced his resignation in an address to the nation, ending his nine-year-long reign on 18 August 2008.[196]

2008–2019: Fourth democratic era

Prime Minister Gilani headed a collective government with the winning parties from each of the four provinces. Pakistan's political structure was changed to replace the semi-presidential system into a parliamentary democracy. Parliament unanimously passed the 18th amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan, which implemented this. It turns the President of Pakistan into a ceremonial head of state and transfers the authoritarian and executive powers to the Prime Minister.[197] In 2009–11, Gillani, under pressure from the public and co-operating with the United States, ordered the armed forces to launch military campaigns against Taliban forces in the north-west of Pakistan. These quelled the Taliban militias in the north-west, but terrorist attacks continued elsewhere. The country's media was further liberalised, and with the banning of Indian media channels Pakistani music, art and cultural activities were promoted at the national level.

In 2010 and 2011 Pakistani-American relations worsened after a CIA contractor killed two civilians in Lahore and the United States killed Osama bin Laden at his home less than a mile from the Pakistan Military Academy. Strong US criticism was made against Pakistan for allegedly supporting bin Laden while Gillani called on his government to review its foreign policy. In 2011 steps were taken by Gillani to block all major NATO supply lines after a border skirmish between NATO and Pakistan. Relations with Russia improved in 2012, following a secret trip by the foreign minister Hina Khar.[198] Following repeated delays by Gillani in following Supreme Court orders to probe corruption allegations he was charged with contempt of court and ousted on 26 April 2012. He was succeeded by Pervez Ashraf.[199][200]

After the parliament completed its term, a first for Pakistan, elections held on 11 May 2013 changed the country's political landscape when the conservative Pakistan Muslim League (N) achieved a near supermajority in the parliament.[201][202] Nawaz Sharif became prime minister on May 28.[203] In 2015, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor was initiated. In 2017, the Panama Papers case resulted in the disqualification of Sharif by verdict of the Supreme Court. Shahid Khaqan Abbasi became Prime Minister afterwards[204] until mid 2018. The PML-N government was dissolved after completion of the parliamentary term.

General elections were held in 2018 which saw the coming of PTI for the first time in the government. Imran Khan was elected Prime Minister[205] with Arif Alvi, Khan's close ally, as president.[206] The Federally Administered Tribal Areas were merged with the neighbouring Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province in 2018.

During Khan’s tenure several new policies were implemented including strict austerity measures,[207] promises to uproot corruption,[208] increased tax collection and a rise in social welfare programs.[209] Khan’s government oversaw a rapid V-shaped recovery of Pakistan’s economy which grew significantly between the years 2018 and 2022.[210][211]

2020–present: Post-COVID era

In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the country.[212] However, the Imran Khan-led government managed to keep the situation under control.[213][214][215] In April 2022, Khan became the country's first prime minister to be removed from office through a no-confidence motion in Parliament.[216] On 11 April 2022, Pakistan's parliament elected Shehbaz Sharif, head of the Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N) party and the younger brother of Nawaz Sharif, as the country's new prime minister to succeed Imran Khan.[217] Khan’s removal sparked major political instability across Pakistan,[218] as his party, the PTI demanded snap elections.[219] As part of the constitutional crises, around 123 National Assembly members loyal to Khan resigned.[220] Khan himself survived an assassination attempt, though he suffered injuries after the attempt, while Khan blamed the incumbent government for the attack.[221][222] Arif Alvi remained the only PTI officeholder in a high government position.[223] Imran Khan was arrested on May 9, 2023 in a controversial move by paramilitary forces,[224] and has remained imprisoned since August 2023, with major protests still ongoing for his release.[225][226] Independent journalism and podcasting on platforms such as YouTube have grown since the Pandemic.[227]

After completing a year and half as prime minister, Shehbaz Sharif handed over the office to Anwar-ul-Haq Kakar who took over as the 8th caretaker prime minister of Pakistan on 14 August 2023 and oversaw the new general elections.[228][229][230] In February 2024, Former Prime Minister Imran Khan's Tehreek-e-Insaf (PTI) party and its allies became the largest group with 93 seats in general elections. However, PTI was forced to name its candidates as independents due to issues with the ECP.[231] In March 2024, the parliament elected Shehbaz Sharif as the new prime minister for a second term. He formed a coalition between his Pakistan Muslim League - Nawaz (PMLN) party and the Pakistan Peoples Party (PPP). The PTI remained in opposition and chose Omar Ayub Khan as opposition head.[232][233]

Major political and financial instability is still ongoing,[234] as PTI lawyers and barristers (registered under the Sunni Ittehad Council due to registration complications) have challenged the February 2024 elections as rigged and fraudulent, further cases emerged including cases involving Imran Khan such as the Iddat case and Lettergate, as well as a case over Pakistan’s parliamentary reserve seats.[235] All three of the aforementioned cases were won Imran Khan and his party. Several cases were overseen by 29th Chief Justice, Qazi Faez Isa. Financial instability is also ongoing, as since 2022, Pakistan’s economy and the value of the Pakistani Rupee has plummeted with constant loans required from the IMF.[236][237] Raging criticism is also ongoing of Pakistan’s Military dubbed ‘The Establishment’, which has been criticized for being involved in Pakistani politics (against Imran Khan), cracking down on civilians and rigging the February 2024 elections.[238][239][240][241] In March 2024, Asif Ali Zardari, Pakistan Peoples Party’s co-chairperson and the widower of Pakistan’s assassinated first female leader, Benazir Bhutto, was voted into the largely ceremonial post of Pakistan’s president for second time in a vote by parliament and regional assemblies.[242]

See also

References

- ^ a b "Information of Pakistan". 23 July 2010. Archived from the original on 23 July 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ "Was Pakistan sufficiently imagined before independence? – The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 23 August 2015. Archived from the original on 8 March 2017. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Ashraf, Ajaz. "The Venkat Dhulipala interview: 'On the Partition issue, Jinnah and Ambedkar were on the same page'". Scroll.in. Archived from the original on 5 December 2016. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ^ "Independence Through Ages". bepf.punjab.gov.pk. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Singh, Prakash K. (2009). Encyclopaedia on Jinnah. Anmol Publications. ISBN 978-8126137794. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

- ^ "Jinnah after Aurangzeb". Outlook India. 5 February 2022. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ^ Qasmi, Ali Usman; Robb, Megan Eaton (2017). Muslims against the Muslim League: Critiques of the Idea of Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1108621236.

- ^ Haq, Mushir U. (1970). Muslim politics in modern India, 1857-1947. Meenakshi Prakashan. p. 114. OCLC 136880.

This was also reflected in one of the resolutions of the Azad Muslim Conference, an organization which attempted to be representative of all the various nationalist Muslim parties and groups in India.

- ^ Ahmed, Ishtiaq (27 May 2016). "The dissenters". The Friday Times. Archived from the original on 22 March 2021. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

However, the book is a tribute to the role of one Muslim leader who steadfastly opposed the Partition of India: the Sindhi leader Allah Bakhsh Soomro. Allah Bakhsh belonged to a landed family. He founded the Sindh People's Party in 1934, which later came to be known as 'Ittehad' or 'Unity Party'. ...Allah Bakhsh was totally opposed to the Muslim League's demand for the creation of Pakistan through a division of India on a religious basis. Consequently, he established the Azad Muslim Conference. In its Delhi session held during April 27–30, 1940 some 1400 delegates took part. They belonged mainly to the lower castes and working class. The famous scholar of Indian Islam, Wilfred Cantwell Smith, feels that the delegates represented a 'majority of India's Muslims'. Among those who attended the conference were representatives of many Islamic theologians and women also took part in the deliberations ... Shamsul Islam argues that the All-India Muslim League at times used intimidation and coercion to silence any opposition among Muslims to its demand for Partition. He calls such tactics of the Muslim League as a 'Reign of Terror'. He gives examples from all over India including the NWFP where the Khudai Khidmatgars remain opposed to the Partition of India.

- ^ Jaffrelot, Christophe (2004). A History of Pakistan and Its Origins. Anthem Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1843311492. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

Believing that Islam was a universal religion, the Deobandi advocated a notion of a composite nationalism according to which Hindus and Muslims constituted one nation.

- ^ Abdelhalim, Julten (2015). Indian Muslims and Citizenship: Spaces for Jihād in Everyday Life. Routledge. p. 26. ISBN 978-1317508755. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

Madani ... stressed the difference between qaum, meaning a nation, hence a territorial concept, and millat, meaning an Ummah and thus a religious concept.

- ^ Sikka, Sonia (2015). Living with Religious Diversity. Routledge. p. 52. ISBN 978-1317370994. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

Madani makes a crucial distinction between qaum and millat. According to him, qaum connotes a territorial multi-religious entity, while millat refers to the cultural, social and religious unity of Muslims exclusively.

- ^ Khan, Shafique Ali (1988). The Lahore resolution: arguments for and against : history and criticism. Royal Book Co. p. 48. ISBN 978-9694070810. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

Besides, Maulana Ashraf Ali Thanvi, along with his pupils and disciples, lent his entire support to the demand of Pakistan.

- ^ a b "'What's wrong with Pakistan?'". Dawn. 13 September 2013. Archived from the original on 9 January 2017. Retrieved 10 January 2017.

However, the fundamentalist dimension in Pakistan movement developed more strongly when the Sunni Ulema and pirs were mobilised to prove that the Muslim masses wanted a Muslim/Islamic state ... Even the Grand Mufti of Deoband, Mufti Muhammad Shafi, issued a fatwa in support of the Muslim League's demand.

- ^ Long, Roger D.; Singh, Gurharpal; Samad, Yunas; Talbot, Ian (2015). State and Nation-Building in Pakistan: Beyond Islam and Security. Routledge. p. 167. ISBN 978-1317448204. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

In the 1940s a solid majority of the Barelvis were supporters of the Pakistan Movement and played a supporting role in its final phase (1940-7), mostly under the banner of the All-India Sunni Conference which had been founded in 1925.

- ^ Kukreja, Veena; Singh, M. P. (2005). Pakistan: Democracy, Development and Security Issues. SAGE Publishing. ISBN 978-9352803323.

The latter two organisations were offshoots of the pre-independence Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind and were comprised mainly of Deobandi Muslims (Deoband was the site for the Indian Academy of Theology and Islamic Jurisprudence). The Deobandis had supported the Congress Party prior to partition in the effort to terminate British rule in India. Deobandis also were prominent in the Khilafat movement of the 1920s, a movement Jinnah had publicly opposed. The Muslim League, therefore, had difficulty in recruiting ulema in the cause of Pakistan, and Jinnah and other League politicians were largely inclined to leave the religious teachers to their tasks in administering to the spiritual life of Indian Muslims. If the League touched any of the ulema it was the Barelvis, but they too never supported the Muslim League, let alone the latter's call to represent all Indian Muslims.

- ^ John, Wilson (2009). Pakistan: The Struggle Within. Pearson Education India. p. 87. ISBN 978-8131725047.

During the 1946 election, Barelvi Ulama issued fatwas in favour of the Muslim League.

[permanent dead link] - ^ Cesari, Jocelyne (2014). The Awakening of Muslim Democracy: Religion, Modernity, and the State. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 978-1107513297. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 18 October 2020.

For example, the Barelvi ulama supported the formation of the state of Pakistan and thought that any alliance with Hindus (such as that between the Indian National Congress and the Jamiat ulama-I-Hind [JUH]) was counterproductive.

- ^ Talbot, Ian (1982). "The growth of the Muslim League in the Punjab, 1937–1946". Journal of Commonwealth & Comparative Politics. 20 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1080/14662048208447395.

Despite their different viewpoints all these theories have tended either to concentrate on the All-India struggle between the Muslim League and the Congress in the pre-partition period, or to turn their interest to the Muslim cultural heartland of the UP where the League gained its earliest foothold and where the demand for Pakistan was strongest.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 19. ISBN 978-1316258385. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 23 September 2017.

Within the subcontinent, ML propaganda claimed that besides liberating the majority province Muslims it would guarantee protection for Muslims who would be left behind in Hindu India. In this regard, it repeatedly stressed the hostage population theory that held that "hostage" Hindu and Sikh minorities inside Pakistan would guarantee Hindu India's good behaviour towards its own Muslim minority.

- ^ Gilmartin, David (2009). "Muslim League Appeals to the Voters of Punjab for Support of Pakistan". In D. Metcalf, Barbara (ed.). Islam in South Asia in Practice. Princeton University Press. pp. 410–. ISBN 978-1400831388. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

At the all-India level, the demand for Pakistan pitted the League against the Congress and the British.

- ^ Kulke, Hermann; Dietmar Rothermund (1986). A History of India. Totowa, New Jersey: Barnes & Noble. pp. 300–312. ISBN 978-0389206705.

- ^ Dhulipala, Venkat (2015). Creating a New Medina: State Power, Islam, and the Quest for Pakistan in Late Colonial North India. Cambridge University Press. p. 496. ISBN 978-1316258385. "The idea of Pakistan may have had its share of ambiguities, but its dismissal as a vague emotive symbol hardly illuminates the reasons as to why it received such overwhelmingly popular support among Indian Muslims, especially those in the 'minority provinces' of British India such as U.P."

- ^ Mohiuddin, Yasmin Niaz (2007). Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook. ABC-CLIO. p. 70. ISBN 978-1851098019. Archived from the original on 16 January 2023. Retrieved 10 August 2017.