Mitcham

| Mitcham | |

|---|---|

Mitcham Clocktower. Built in 1898 and renovated in 2016 | |

Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 63,393 (2011 Census)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ285685 |

| London borough | |

| Ceremonial county | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | MITCHAM |

| Postcode district | CR4 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | Metropolitan |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

Mitcham is an area within the London Borough of Merton in Southwest London, England. It is centred 7.2 miles (11.6 km) southwest of Charing Cross. Originally a village in the county of Surrey, today it is mainly a residential suburb, and includes Mitcham Common. It has been a settlement throughout recorded history.

Amenities include Mitcham Library and Mitcham Cricket Green. Nearby major districts are Croydon, Sutton, Streatham, Brixton and Merton. Mitcham, most broadly defined, had a population of 63,393 in 2011, formed from six wards including Pollards Hill.[2]

Location

[edit]Mitcham is in the east of the London Borough of Merton. Mitcham is close to Streatham, Croydon, Norbury, Morden, Sutton, Wimbledon, Colliers Wood and Tooting. The River Wandle bounds the town to the southwest.[3] The original village lies in the west. Mitcham Common takes up the greater part of the boundary and the area to the south part of the CR4 postcode is in the area of Pollards Hill. Some of the area which includes Mitcham Common and parts of Mitcham Junction are in the CR0 postcode area.

History

[edit]

The toponym "Mitcham" is Old English in origin and means big settlement. Before the Romans and Saxons were present, it was a Celtic settlement, with evidence of a hill fort in the Pollards Hill area. The discovery of Roman-era graves and a well on the site of the Mitcham gasplant evince Roman settlement. The Anglo-Saxon graveyard on the north bank of the Wandle is the largest discovered to date, and many of the finds therein are on display in the British Museum. Scholars such as Myres have suggested that Mitcham and other Thames plain settlements were some of the first populated by the Anglo-Saxons.

What became the parish lands could have hosted the Battle of Merton, 871, in which King Ethelred of Wessex was either mortally wounded or killed outright. The Church of England parish church of St Peter and St Paul dates from the early Kingdom of England. Mostly rebuilt in 1819–1821, the current building retains the original Saxon tower. The Domesday Book of 1086 lists Mitcham as a small farming community, an implied estimate of 250 people, living in two hamlets: Mitcham, the area today being Upper Mitcham; and Whitford (Lower Green).

The Domesday Book records Mitcham as Michelham. It was held partly by the Canons of Bayeux, partly by William, son of Ansculf and partly by Osbert.[4] Its domesday assets were: 8 hides and 1 virgate. It had ½ mill worth £1, 3½ ploughs, 56 acres (23 ha) of meadow. It rendered £4 5s 4d, at a time when a pound sterling still implied something similar to a pound of silver. The area lay in the Anglo-Saxon county subdivision of Wallington hundred.[5]

During her reign Queen Elizabeth I made at least five visits to the area. John Donne and Sir Walter Raleigh also had residences here in this era. It was at this time that Mitcham became gentrified, as due to the abundance of lavender fields Mitcham became renowned for its soothing air. The air also led people to settle in the area during times of plague.

When industrialisation occurred, Mitcham quickly grew to become a town and most of the farms were swallowed up in the expansion. Remnants of this farming history today include: Mitcham Common itself; Arthur's Pond on the corner of Watney's Road and Commonside East, and named for a local farmer; Alfred Mizen School (Garden Primary School), named after a local nurseryman charitable towards the burgeoning town; and the road New Barnes Avenue, replacing part of New Barn(e)s Farm.

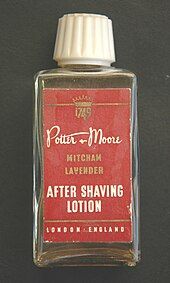

Many lavender fields were in Mitcham, and peppermint and lavender oils were also distilled. In 1749 two local physic gardeners, John Potter and William Moore, founded a company to make and market toiletries made from locally grown herbs and flowers.[6] Lavender features on Merton Council's coat of arms and the badge of the local football team, Tooting & Mitcham United F.C., as well as in the name of a local council ward, Lavender Field.

Mitcham was industrialised first along the banks of the Wandle, where snuff, copper, flour, iron and dye were all worked. Mitcham, along with nearby Merton Abbey, became the calico cloth printing centres of England by 1750. Asprey, suppliers of luxury goods made from various materials, was founded in Mitcham as a silk-printing business in 1781. William Morris opened a factory on the River Wandle at Merton Abbey. Merton Abbey Mills were the Liberty silk-printing works. It is now a craft village and its waterwheel has been preserved.

Activity along the Wandle led to the building of the Surrey Iron Railway, the world's first public railway, in 1803. The decline and failure of the railway in the 1840s also heralded a change in industry, as horticulture gradually gave way to manufacturing, with paint, varnish, linoleum and firework manufacturers moving into the area. The work provided and migratory patterns eventually resulted in a doubling of the population between the years 1900 and 1910.

In 1829 Miss Mary Tate donated land and money to build almshouses on the site of the former Tate family home in Cricket Green. The buildings were designed in a Tudor style by John Butcher and established to accommodate twelve poor widows or spinsters of the parish. Miss Tate was the only surviving member of the Tate family, who had lived from about 1700 in a large mansion on the site of the almshouses.[7][8] The gardens at the rear of the property were originally provided for the use of residents, but later informally rented out as allotments.[9]

Mitcham became a borough, within a two-tier council system, on 19 September 1934 with the charter of incorporation being presented to the 84-year-old mayor, R.M. Chart, by the Lord Lieutenant of Surrey, Lord Ashcombe.[10]

| 19th Century | 20th Century | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1801 | 3,466 | 1901 | 14,903 |

| 1811 | 4,175 | 1911 | 29,606 |

| 1821 | 4,453 | 1921 | 35,119 |

| 1831 | 4,387 | 1931 | 56,859 |

| 1841 | 4,532 | 1941¹ | war |

| 1851 | 4,641 | 1951 | 67,269 |

| 1861 | 5,078 | 1961 | 63,690 |

| 1871 | 6,498 | 1971 | 60,608 |

| 1881 | 8,960 | 1981 | 57,158 |

| 1891 | 12,127 | 1991² | n/a |

| |||

| source: UK census | |||

Social housing schemes in the 1930s included New Close, aimed at housing people made homeless by a factory explosion in 1933 [citation needed] and Sunshine Way, for housing the poor from inner London.[11] This industry made Mitcham a target for German bombing during World War II. During this time Mitcham also returned to its agricultural roots, with Mitcham Common being farmed to help with the war effort.[citation needed]

From 1929 the electronics company Mullard had a factory on New Road.[citation needed]

Postwar, the areas of Eastfields, Phipps Bridge and Pollards Hill were rebuilt to provide cheaper more affordable housing.[citation needed] The largest council housing project in Mitcham is Phipps Bridge Estate.[citation needed] Further expansion of the housing estates in Eastfields, Phipps Bridge and Pollards Hill occurred after 1965. In Mitcham Cricket Green, the area lays reasonable, although not definitive, claim to having the world's oldest cricket ground in continual use, and the world's oldest club in Mitcham Cricket Club.[12]

The ground is also notable for having a road separate the pavilion from the pitch.[12] Local folklore claims Mitcham has the oldest fair in England, believing it to have been granted a charter by Queen Elizabeth I, a claim never proven.

- Literature

Nimrod, sporting writer of the early 19th century, advocated against the grazing on grass of racehorses. He finds a very fast donkey chaise, investigates the donkey's owner and finds it is a Mitcham blacksmith, who never turns out the donkey in summer onto Mitcham Common but keeps it fed with oats and beans as if a hunter racing horse.[13]

Mitcham appears in local variants of mildly vulgar rhymes of 18th and 19th centuries, all beginning with:

One variant ends with "Mitcham for a thief", another "Ewell" which is opposite in direction. An author noted for another genre, James Edward Preston Muddock as Dick Donovan penned The Naughty Maid of Mitcham in 1910.

Open spaces

[edit]

Mitcham is home to a large area (460 acres) of South London's open green space in the form of Mitcham Common, studded with a few ponds and buildings.

The buildings comprising the Windmill Trading Estate have existed in one form or another since 1782. The Mill House Ecology Centre and the Harvester (formerly the Mill House Pub) are located near the site of an old windmill, the remnants of which still exist.

The Seven Islands pond is the largest of all the ponds, created following gravel extraction of the 19th century.[15] The most recent, Bidder's pond, was created in 1990 and named after George Parker Bidder.

Notable buildings

[edit]-

Eagle House, Mitcham

-

Old Mitcham Station

-

Mitcham Library, London Rd

-

Elm Lodge, Cricket Green

-

Mitcham Methodist Church

-

St Barnabas Church

-

The White House, Mitcham

-

The White Hart Public House

- The Canons. House originally built in 1680; it was the home of the family Cranmer until it was sold to the local council in 1939. The name originates from an Augustinian priory that was given this site in the 12th Century. The pond next to which it is located and the dovecote (dated at 1511) both predate the house.[16]

- Eagle House, built in 1705. Eagle House is a Queen Anne house built in the Dutch style on land formerly owned by Sir Walter Raleigh. It is on London Road, Mitcham, the grounds forming a triangle bounded by London Road, Bond Road and Western Road. The building was commissioned by the marrano doctor Fernando Mendes (1647–1724), former physician to King Charles II.

- Mitcham Common Windmill, a post mill dating from 1806.

- Old Mitcham Station, on the Surrey Iron Railway route. Now called Station Court, the building was a former merchant's home and is possibly the oldest station in the world.

- The Tate Almshouses, built in 1829 to provide for the poor by Mary Tate.

- The Watermead Fishing Cottages.

- Mitcham Vestry Hall, the annex of which now houses the Wandle Industrial Museum.

- Mitcham Public Library, built in 1933.

- Elm Lodge, 1808. This listed Regency house was occupied by Dr. Parrott, a village doctor, in the early 19th century, and for a short time by the artist, Sir William Nicholson. The curved canopy over the entrance door is a typical feature of this period.[citation needed]

- Mitcham Court. The centre portion, first known as Elm Court, was built in 1840, the wings later. Caesar Czarnikow, a sugar merchant, lived here ca. 1865–86 and presented the village with a new horse-drawn fire engine. Sir Harry Mallaby-Deeley, M.P., conveyed the house to the borough in the mid-1930s. The Ionic columned porch and the ironwork on the ground floor windows are notable features.

- Renshaw's factory, a marzipan factory, founded in 1898 in the City and thus one of the earliest in the country, which came to Mitcham in 1924.[citation needed] It was on Locks Lane until 1991, when the company moved its operations to Liverpool. The factory was featured in three 1950s British Pathé News shorts. The building has lent its name to the area where it stood, Renshaw Corner.

- Poulters Park, Home to Mitcham Rugby Union Football Club

- Imperial Fields, Tooting & Mitcham United F.C.'s home ground.

- Mitcham Methodist Church was designed by the architect Edward Mills (1915–1998), and built in 1958–9. Regarded as the best surviving work by the most successful Nonconformist architect of the period. A radical and inspiring building that was forwarded by the 20th Century Society for listing as it was under threat. Grade II listed on 5 March 2010.[17]

- St Barnabas church, Gorringe Park Avenue, Mitcham. Built in the gothic style, on 17 May 1913 the foundation stone of the church building was laid, and on 14 November 1914 the church was consecrated – by the bishop of Southwark. The architect was HP Burke-Downing. The building is still in use as an Anglican church. Both the church itself and the adjacent parish hall are Grade II listed.

- The White House, Mitcham on which the wall plaque says: "This 18th Century house was renovated in the Regency style in 1826 by Dr. A.C. Bartley, a village doctor, whose daughter wrote reminiscences of old Mitcham. The house remained in his family until 1919. Fluted Greek Doric columns support a slightly altered porch with a bowed front." It is Grade II listed.[18]

- The Burn Bullock, a public house, London Road, Mitcham is a three-storey Grade II listed building originally called the King's Head Hotel. The front of the building dates from the 18th century whilst its wing dates from the 16th and 17th centuries.[19] It is named after Burnett Bullock, a well known, former cricket player from the locality.[20][12]

- The White Hart public house is Mitcham's earliest recorded inn, rebuilt in 1749–50 after serious fire damage. The central porch, with frieze and balustrade, is supported by four Tuscan columns. Stagecoaches used to start from a yard at the rear. It is Grade II listed. It is located in London Road, opposite Cricket Green.[21]

Notable people

[edit]- Ramz (rapper) - singer, rapper[22]

- John Donne – Jacobean poet and churchman[23]

- James Chuter Ede – politician, MP for Mitcham 1923, resident till 1937, later Home Secretary[24]

- Michael Fielding and Noel Fielding – The Mighty Boosh comedians and brothers[25]

- Mike Fillery – Association football[26]

- David Gibson – cricketer[27]

- Florence Harmer – historian[28]

- Neil Howlett – opera singer[29]

- Banaz Mahmod, 20, an Iraqi Kurd, victim of honour killing in 2006[30]

- M.I.A. – singer, songwriter and rapper[31]

- Peter D. Mitchell — Nobel prizewinner, born in Mitcham in 1920[32]

- Slick Rick – East coast Rapper, born in Surrey, moved to USA aged 11[33]

- Alex Stepney – former Manchester United footballer and 1968 European Cup winner[34]

- Herbert Strudwick – cricket wicket-keeper[35]

- William Allison White – recipient of the Victoria Cross[36]

- Faryadi Sarwar Zardad – Afghan warlord; lived in Mitcham for a time, later convicted and imprisoned for war crimes[37]

Demography and economics

[edit]- Mitcham and Morden (Westminster Parliamentary Constituency)

- Population – 103,298[38]

- Ethnic Group[39]

British – 40,608, Irish – 1,840, Gypsy or Irish Traveller – 161, Other White – 12,899

White and Black Caribbean – 1,862, White and Black African – 856, White and Asian – 1,163, Other Mixed – 1,444

Indian – 4,536, Pakistani – 5,054, Bangladeshi – 1,484, Chinese – 1,169, Other Asian – 10,194

- Black/African/Caribbean

African – 9,036, Caribbean – 7,029, Other Black – 1,912

- Other Ethnic Group

Arab – 670, Other ethnic group – 1,381

- Religion[40]

Buddhist – 862, Sikh – 252, Jewish – 147, Other Religion – 362

- Gender[41]

- Female: 52,237

- Male: 51,061

| By property type | Number of sales last 12 months | Average price achieved last 12 months | Average price change per square foot |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detached | 5 | £525,404 | –20.9% |

| Semi-detached | 46 | £531,304 | 6.5% |

| Terraced | 279 | £478,749 | 3.3% |

| Flat/Apartment | 212 | £276,956 | 4.9% |

Transport and locale

[edit]

Mitcham is served by two railway stations: Mitcham Junction and Mitcham Eastfields. Mitcham Eastfields was the first suburban station to be built in 50 years in the area.[citation needed] Both stations are served by Govia Thameslink Railway's Southern and Thameslink brands with trains to Sutton, Epsom, London Victoria, London Bridge (peaks only) and St Albans.[43][44]

Trains on the Thameslink route from Central London continue on via the Sutton Loop Line to Sutton and Wimbledon back towards Central London. Tramlink also serves Mitcham with four stops in the area; Mitcham Junction, Mitcham, Belgrave Walk and Phipps Bridge. Trams provide a direct service to Wimbledon, Croydon, Beckenham Junction and Elmers End from Mitcham and also New Addington with a change at Croydon.

Bus

[edit]Bus services operated by London Buses are available from Mitcham. These include night buses to Aldwych and Liverpool Street in central London.[45]

Coach

[edit]National Express services 028 London Victoria to Eastbourne, 025 London Victoria to Brighton and Worthing via Gatwick Airport, 026 London Victoria to Bognor Regis and A3 London Victoria to Gatwick Airport hourly shuttle all stop at Mitcham (Downe Road/Mitcham Library bus stop)[46]

Footnotes

[edit]- "Merry Making at Mitcham". Wayback Machine. The University of Sheffield's National Fairground Archive. Archived from the original on 21 December 2004.

- "Making Merton". Merton Council. Archived from the original on 26 April 2009.

- "A Brief History of Merton by John Precedo: Part 1 – Romans to the Norman Conquest". Wayback Machine. Tooting Community Website. Archived from the original on 13 April 2005.

- Eric Norman Montague (1976). The 'Canons' Mitcham. Merton Historical Society. ISBN 0-9501488-3-0.

- Eric Norman Montague (2001). North Mitcham. Merton Historical Society. ISBN 1-903899-07-9.

- Eric Norman Montague (1996). The Historic River Wandle: Phipps Bridge to Morden Hall. Merton Historical Society. ISBN 0-905174-25-9.

References

[edit]- ^ Mitcham is made up of 6 wards in the London Borough of Merton: Cricket Green, Figge's Marsh, Graveney, Lavender Fields, Longthornton, and Pollards Hill."2011 Census Ward Population Estimates | London DataStore". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ "2011 Census Ward Population Estimates | London DataStore". Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 9 June 2014.

- ^ Ordnance Survey

- ^ "Surrey". The Domesday Book online – Surrey.

- ^ "Open Domesday: Mitcham". Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ "Potter and Moore – An Introduction". Potter & Moore.

- ^ "Mary Tate Almshouses – Merton Memories Photographic Archive". photoarchive.merton.gov.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ MISS TATE'S ALMSHOUSES, MITCHAM.

- ^ "Mary Tate Almshouses". www.londongardensonline.org.uk. Retrieved 13 June 2019.

- ^ Daily Mirror page 13, 19 September 1934

- ^ "New cottages by the church army". Church Times. 13 November 1936. Retrieved 16 November 2022.

- ^ a b c Siddique, Haroon (19 August 2018). "World's oldest village cricket green under threat from developers, club says". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 August 2018.

- ^ Pierce Egan, Pierce Egan's Anecdotes (original and Selected) of the Turf, the Chase, the Ring, and the Stage, Knight & Lacey, 1827, at page 57

- ^ "Chapter XIV: Local Allusions to Women". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 5 December 2013.

- ^ wandlevalleypark.co.uk

- ^ "The Canons, Mitcham: Dovecote – Merton Memories Photographic Archive". photoarchive.merton.gov.uk. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- ^ "Mitcham Methodist Church, exterior (E. Mills)". Flickr. 8 April 2010.

- ^ Historic England

- ^ "British Listed Buildings: Burn Bullock Public House, Merton". britishlistedbuildings.co.uk.

- ^ "Burn Bullock, Mitcham, Surrey". ukpubfinder.com.

- ^ Mitcham History Notes

- ^ Amarudontv (26 December 2017), Ramz [Interview] Overcoming Exclusion From Secondary School And Growing Up In South London, retrieved 3 January 2018

- ^ Colclough, David (19 May 2011). "Donne, John (1572–1631)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/7819. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ 'Lady Griffith-Boscawen cries over Mitcham result', Daily Graphic (4 March 1923), and other newspaper articles

- ^ Rumbelow, Helen (28 November 2009). "The Mighty Boosh's Noel Fielding says that 'Kids are frightened of me'". The Sunday Times. London. Retrieved 19 October 2010.

- ^ Mitcham at Post War English & Scottish Football League A–Z Player's Transfer Database

- ^ David Lemmon, The History of Surrey County Cricket Club, Christopher Helm, 1989, ISBN 0-7470-2010-8, p253.

- ^ Dorothy Whitelock, 'Florence Elizabeth Harmer', in Interpreters of Early Medieval Britain, pp. 369-380

- ^ David M. Cummings, ed. (2000). International Who's Who in Music. Routledge. p. 268. ISBN 0-948875-53-4.

- ^ McVeigh, Tracy (22 September 2012). "'They're following me': chilling words of girl who was 'honour killing' victim". The Observer. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- ^ Wheaton, Robert (6 May 2005). "London Calling – For Congo, Columbo, Sri Lanka." PopMatters. Archived from the original on 24 January 2009. Retrieved 6 May 2007.

- ^ "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/51236. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ Bush, John. "Slick Rick Biography and History". AllMusic. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- ^ Bethel, Chris; Sullivan, David (2002). Millwall Football Club 1940–2001. Tempus Publishing. p. 56. ISBN 0-7524-2187-5.

- ^ Herbert Strudwick at ESPNcricinfo

- ^ "Merton: Carved in Stone: William Allison White". Retrieved 30 October 2022.

- ^ John Simpson (18 July 2005). "How Newsnight found Zardad". BBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2007.

- ^ "Population Density, 2011". Area: Mitcham and Morden (Westminster Parliamentary Constituency). Office for National Statistics. Archived from the original on 2 June 2015. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

- ^ "Ethnic Group, 2011". Area: Mitcham and Morden (Westminster Parliamentary Constituency). Office for National Statistics.

- ^ "Religion, 2011". Area: Mitcham and Morden (Westminster Parliamentary Constituency). Office for National Statistics.

- ^ "Se, 2011". Area: Mitcham and Morden (Westminster Parliamentary Constituency). Office for National Statistics.

- ^ "Mitcham Property Market Snapshot". Truuli. Retrieved 11 March 2023.

- ^ Mitcham Junction National Rail

- ^ Mitcham Eastfields National Rail

- ^ Buses and trams from Mitcham Junction Transport for London

- ^ "London (Mitcham) — National Express Coach Tracker". coachtracker-embed.nationalexpress.com. Retrieved 5 October 2019.