Progestogen-only pill

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (November 2023) |

| Progestogen-only pill | |

|---|---|

| Background | |

| Type | Hormonal |

| First use | 1968[1][2] |

| Failure rates (first year) | |

| Perfect use | 0.3%[3] |

| Typical use | 9%[3] |

| Usage | |

| Duration effect | 1 day |

| Reversibility | Yes |

| User reminders | Taken within same 3-hour window each day |

| Clinic review | 6 months |

| Advantages and disadvantages | |

| STI protection | No |

| Weight | No proven effect |

| Period disadvantages | Light spotting may be irregular |

| Period advantages | Often lighter and less painful |

| Medical notes | |

| Unaffected by being on most (but not all) antibiotics. May be used, unlike COCPs, in patients with hypertension and history of migraines. Affected by some anti-epileptics. | |

Progestogen-only pills (POPs), colloquially known as "mini pills", are a type of oral contraceptive that contain synthetic progestogens (progestins) and do not contain estrogens.[4] They are primarily used for the prevention of undesired pregnancy, although additional medical uses also exist.[5]

Progestogen-only pills differ from combined oral contraceptive pills (COCPs), which instead consist of a combination of synthetic estrogens and progestin hormones.[6]

Terminology

[edit]"Progestogen-only pills," "Progestin-only pills," and "Progesterone-only pills" are terms each referring to the same class of synthetic hormone medications. The phrase "Progestogen-only pill" is used by the World Health Organization and much of the international medical community.[7] The phrase "Progestin-only pills" is typically used in the United States and Canada.[8]

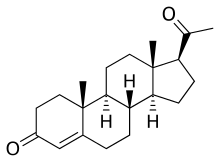

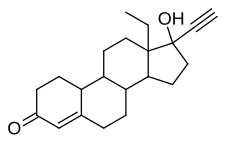

Despite sometimes being referred to as "Progesterone-only pills," these medications do not contain progesterone but instead one of several chemically related compounds.[9] For example, the medication Opill contains the synthetic hormone Norgestrel, which has some distinct chemical differences despite producing a similar physiological effect.[10]

Available formulations

[edit]Progestogens share the common feature of being able to bind to the body's progesterone receptors and enact a physiological effect similar to naturally occurring progesterone.[11] Still, there are differences between progestogens, and various organizational systems exist to categorize the progestogen hormones used in oral contraception medications.

By Generation - based on when it became available for use, each synthetic hormone can be grouped into 1 of 4 generations of medications.[12] A medication's generation is not necessarily a reflection of safety or efficacy.

By Additional Receptor Activity - each medication may act upon other receptors such as androgen receptors, estrogen receptors, glucocorticoid receptors, and mineralocorticoid receptors. Additional interactions may be positive, increasing activity at a given receptor, or negative, decreasing activity at a given receptor. The overall profile of these additional actions for each medication can be used to describe and contrast progestogens.[13]

| Generic Formulation (Dose) | Generation | Brand name(s) | Additional receptor activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Desogestrel (75 μg) | 3rd | Cerazette

Cerelle |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-) Androgen (+) |

| Drospirenone (4 mg) | 4th | Slynd | Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-) Androgen (-) Mineralocorticoid (-) |

| Norethisterone (350 μg) | 1st | Micronor

Nor-QD Noriday |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-/+) Pro-androgen (+) Coagulation (+) |

| Norgestrel (0.075 mg) | 2nd | Opill | |

| Etynodiol diacetate (500 μg) | 1st | Femulen | |

| Levonorgestrel (30 μg) | 2nd | 28 mini

Microval Norgeston |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-) Androgen (+) |

| Lynestrenol (500 μg) | 1st | Exluton

Mini-kare |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-/+) Androgen (+) |

| Norethindrone or Norethisterone (300 μg) | 1st | Camila

Mini-Pe Errin Heather Jolivette Micronor Nor-QD Nora-BE Lyza Sharobel Deblitane |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-/+) Androgen (+) Coagulation (+) |

| Norgestrel (75 μg) or Levonorgestrel (37.5 μg) | 2nd | Minicon

Neogest Ovrette Opill |

Gonadotropin (-)

Estrogen (-) Androgen (+) |

| Chlormadinone acetate (0.5 mg) | 1st | Belara

Lutéran Prostal |

|

| Quingestanol acetate (0.3 mg) | - | Demovis

Pilomin |

In the United States, progestogen-only pills are available in 350-μg Norethisterone, 4-mg Drospirenone and Norgestrel 0.075-mg formulations.[18] Norgestrel is FDA-approved for over-the-counter availability,[19] and Norethindrone and Drospirenone are available by prescription.

Medical uses

[edit]Progestogen-only pills are one management option for the suppression of menstruation to avoid pregnancy.[20]

With "perfect use," the efficacy of progestogen-only pills in avoiding unintended pregnancy has been found to be greater than 99%, meaning that less than 1 out of every 100 patients will experience undesired pregnancy within the first year of use.[16] "Perfect use" means that an individual uses their contraceptive pill at the same time every day without missing a scheduled dose.[21]

Assuming "typical use," the theoretical efficacy of progestogen-only pills in avoiding undesired pregnancy falls to around 91-93%, meaning that approximately 7 to 9 out of every 100 patients will experience an unintended pregnancy within the first year of use.[22][23] "Typical use" means that an individual uses their contraceptive pill at inconsistent times day to day and/or misses scheduled doses.[21] The study reporting the "typical use" failure rate failed to differentiate COCPs and POPs as distinct medications and instead studied them as a combined group, decreasing the validity of this finding. The results were published before the widespread use of progestogen-only pills other than Norethindrone and may not be applicable to formulations that have since been developed. Reported efficacy varies between types of progestogen-only pills. For example, Norgestrel has a reported failure rate of 2%,[24] and Drosperinone has a reported failure rate of 1.8%.[25]

Some progestogen-only formulations, such as those containing Norethindrone, were thought to have a shorter duration of effect than COCPs.[26] As a result, current guidelines recommend no more than 27 hours between doses to ensure effectiveness, creating a 3-hour window of variability.[27] However, a more recent meta-analysis suggested that there is actually a significantly longer half-life for many of the now available progestogen-only pill formulations. For example, Norgestrel and Drosperinone, in particular, appear to have a longer window of efficacy. More variation in dose timing may still effectively prevent pregnancy.[28] Although the 3-hour window is still widely respected, some researchers have expressed their belief that an update to these guidelines may be beneficial.[29]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Depending on the specific progestogen and its corresponding dose, the contraceptive effect of progestogen-only pills is enacted through combinations of the following mechanisms:[30]

- Thickening the cervical mucus reduces sperm viability, sperm penetration, and decreases the likelihood of fertilization.[31]

- Inhibition of ovulation through an action on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis. For a low-dose formulation, this may occur inconsistently in ~50% of cycles.[32] Intermediate-dose formulations, such as the progestogen-only pill Cerazette (Desogestrel), much more consistently inhibit ovulation in 97–99% of cycles.[33]

- Alteration of the endometrial lining of the uterus through modification of the structure of endometrial glands and their corresponding secretary patterns, as well as causing the endometrial lining to thin out (atrophy). Overall, the endometrium becomes less suitable for implantation of a fertilized egg and the likelihood of a viable pregnancy decreases.[34]

- Reduction of fallopian tube motility leading to a slowing of the transport of eggs and sperm through the reproductive tract. The process of fertilization as well as implantation are both time sensitive events. Disruption of the normal movement of these reproductive cells plays a role in preventing a viable pregnancy, although the magnitude of this role is likely less significant than previously mentioned mechanisms of action.[34][12]

Breastfeeding

[edit]Patients who have recently given birth may benefit from contraception, as experiencing another pregnancy within six months of delivery is associated with poor outcomes for the second pregnancy.[35] Lactational amenorrhea, although a common and effective method of preventing unwanted pregnancy following childbirth, may not be attainable for mothers who elect for or require supplemental or total child feeding with formula.[36] Combined oral contraceptives are not typically recommended until six months following delivery. Progestogen-only pills, however, can be a viable contraceptive option for patients immediately following delivery regardless of breastfeeding habits.[23]

Comparison to combined oral contraceptives

[edit]Patient groups who choose COCPs versus 'progestogen-only pills may also differ in important ways, as progesterone-only pills are often preferentially prescribed to subfertile groups such as recently postpartum women or older women. Progestogen-only pills may also be prescribed for individuals wanting an oral form of birth control but do not wish to use estrogen-containing methods due to medical contraindications, intolerable side effects, or personal preference.[8] Examples of contraindications to estrogen-containing methods of contraception include relatively common conditions such as hypertension, migraine headaches with aura, or a history of pulmonary embolism or deep vein thrombosis.[37] On the other hand, progestogen-only pills are safe for use by all these groups.[38] The progestogen-only pill is also recommended for people who have recently given birth and desire a pill for contraception, given the risk of blood clots for both postpartum patients and people using estrogen-containing methods of contraception.[39]

Abnormal uterine bleeding

[edit]Given their ability to impact the menstrual cycle and stabilize the endometrial lining of the uterus, progestogen-only pills may also be used to treat various patterns of abnormal uterine bleeding.[40]

Patients with unexplained, abnormal uterine bleeding should be evaluated by a medical professional either through appointment or through a visit to the emergency department. The initial assessment of abnormal uterine bleeding typically focuses on ensuring the patient is medically stable and not in any immediate danger from the underlying cause or associated blood loss. The PALM-COEIN classification system has been developed to understand well-known causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in reproductive-age patients.[41] Understanding the underlying cause of bleeding is an important part of determining the best next step for treatment in each patient's circumstance. Generally, the treatment of abnormal uterine bleeding focuses on controlling the current episode of bleeding and reducing further blood loss in future menstrual cycles or acute episodes.[citation needed]

Depending on the presumed underlying cause of bleeding, medical management with progestogen-only pills, combined oral contraceptives, or tranexamic acid may be appropriate. One study found that 76% of patients who took oral medroxyprogesterone acetate (20 mg) for treatment of bleeding unrelated to pregnancy saw resolution of their bleeding. The median time to resolution was 3 days from beginning medical therapy.[42]

The decision to use POPs to treat abnormal uterine bleeding should be made in consultation with a medical professional who can offer guidance on the appropriateness of this treatment option.[citation needed]

Adenomyosis

[edit]Patients with adenomyosis may be prescribed progestogen-only pills as a part of their treatment. Through their ability to cause amenorrhea, progestogen-only pills can help reduce the symptoms associated with this condition. Levonorgestrel-IUDs may be more effective than progestogen-only pills and reducing associated bleeding (maintaining healthy hemoglobin levels), uterine volume, and pain, although both methods have shown a beneficial impact. That being said, there is currently no definitive treatment guideline, and management can be tailored based on the patient's medical history, preferences, and response to treatment.[43]

Endometriosis

[edit]Patients experiencing mild to moderate pelvic pain from endometriosis may be given non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as well as hormonal contraceptives (COCPs or POPs) to help manage their symptoms. For a long time, combined oral contraceptives have been used as the first-line hormonal contraceptive (vs. progestogen-only pills) for the treatment of endometriosis. However, progestogen-only pills, including dienogest, medroxyprogesterone acetate, norethisterone, and cyproterone, are also effective in treating symptoms (i.e., pain, excess uterine bleeding), reducing associated lesions, and improving patient quality of life.[44][45] Recognizing that some patients cannot receive combined oral contraceptives due to a contraindication to the estrogen component, these findings show promise that progestogens can be an alternative therapy capable of producing adequate symptom relief. Progestogen-only pills are typically not given to patients experiencing severe symptoms.[citation needed]

Decreased likelihood of malignancy

[edit]Daily progesterone use decreases the risk of endometrial cancer,[46] whereas it is unclear whether POPs provide protection against ovarian cancer to the extent that COCPs do.[citation needed]

Side effects

[edit]Genitourinary

[edit]- Irregular menstrual bleeding and spotting in individuals taking progestogen-only pills, especially in the first months after starting.[47][48] This side effect may be bothersome but is not dangerous, and most users report improved bleeding patterns with longer usage.

- May cause mastalgia (breast tenderness, pain)

- Available data on the average impact of POPs on mood are limited and conflicting, and do not show a clear link between POP usage and mental health changes.[49] However, some patients may experience mood swings, including feelings of anxiety and depression.

- Follicular ovarian cysts are more common in POP users than in those not using hormones.[50] The follicular changes tend to regress over time, and no intervention other than reassurance is required in asymptomatic individuals.

Breast cancer risk

[edit]Epidemiological evidence on POPs and breast cancer risk is based on much smaller populations of users and so is less conclusive than that for COCPs.

In the largest (1996) reanalysis of previous studies of hormonal contraceptives and breast cancer risk, less than 1% were POP users. Current or recent POP users had a slightly increased relative risk (RR 1.17) of breast cancer diagnosis that just missed being statistically significant. The relative risk was similar to that found for current or recent COCP users (RR 1.16), and, as with COCPs, the increased relative risk decreased over time after stopping, vanished after 10 years, and was consistent with being due to earlier diagnosis or promoting the growth of a preexisting cancer.[51][52]

The most recent (1999) IARC evaluation of progestogen-only hormonal contraceptives reviewed the 1996 reanalysis as well as 4 case-control studies of POP users included in the reanalysis. They concluded that: "Overall, there was no evidence of an increased risk of breast cancer".[53]

Recent anxieties about the contribution of progestogens to the increased risk of breast cancer associated with HRT in postmenopausal women such as found in the WHI trials[54] have not spread to progestogen-only contraceptive use in premenopausal women.[30]

Depression

[edit]There is a growing body of research investigating the links between hormonal contraception, such as the progestogen-only pill, and potential adverse effects on women's psychological health.[55][56][57] The findings from a large Danish study of one million women (followed-up from January 2000 to December 2013) were published in 2016, and reported that the use of hormonal contraception, particularly amongst adolescents, was associated with a statistically significant increased risk of subsequent depression.[56] The authors found that women on the progestogen-only pill in particular, were 34% more likely to subsequently take anti-depressants or be given a diagnosis of depression, in comparison with those not on hormonal contraception.[56] In 2018, a similarly large nationwide cohort study in Sweden amongst women aged 12–30 (n=815,662) found an association, particularly amongst adolescents aged 12–19, between hormonal contraception and subsequent use of psychotropic drugs.[55] Still, the results of these studies are inconclusive because they are observational and cannot establish causality. Additionally, the studies do not account for the possibility of confounding factors, such as preexisting health conditions, which could influence the results.[58]

Weight gain

[edit]There is some evidence that progestogen-only contraceptives may lead to slight weight gain (on average less than 2 kg in the first year) compared to women not using any hormonal contraception.[59]

History

[edit]The first POP to be introduced contained 0.5 mg chlormadinone acetate and was marketed in Mexico and France in 1968.[1][2][17] However, it was withdrawn in 1970 due to safety concerns pertaining to long-term animal toxicity studies.[1][2][17] Subsequently, levonorgestrel 30 μg (brand name Microval) was marketed in Germany in 1971.[60][61] It was followed by a number of other POPs shortly thereafter in the early 1970s, including etynodiol diacetate, lynestrenol, norethisterone, norgestrel, and quingestanol acetate.[60][62] Desogestrel 75 μg (brand name Cerzette) was marketed in Europe in 2002 and was the most recent POP to be introduced.[63][62][64] It differs from earlier POPs in that it is able to inhibit ovulation in 97% of cycles.[62][64]

In July 2023, the USA Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first over-the-counter (OTC) POP birth control pill to be sold without a prescription in the United States. The pill, marketed under the brand name Opill, is once daily 0.075 mg oral norgestrel.[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Annetine Gelijns (1991). Innovation in Clinical Practice: The Dynamics of Medical Technology Development. National Academies. pp. 172–. NAP:13513.

Development of the minipill, which contains only a progestin, was another result of concerns over the thromboembolic side effects of combination oral contraceptives.36 This development was also driven by the expectation that lower steroid doses would diminish effects on the metabolic and reproductive systems, lessen complaints about nausea and headache, and improve compliance (because it offered a regimen of continuous pill taking rather than the cyclic regimen of earlier pill formulations).37 Syntex was the first to introduce a 0.5 milligram chlor- madinone acetate minipill in 1968 in France, although this pill was withdrawn from the market in 1970 when long-term animal toxicity tests for the FDA revealed the occurrence of breast nodules in beagles.38 Nevertheless, other manufacturers began to pursue minipill development using their own progestogens, and since 1970 a variety of compounds have been introduced.

- ^ a b c Bennett, John P. (1974). "The Second Generation of Hormonal Contraceptives". Chemical Contraception. pp. 39–62. doi:10.1007/978-1-349-02287-8_4. ISBN 978-1-349-02289-2.

Chlormadinone acetate was the first minipill contraceptive to be marketed, in Mexico during July 1968. This compound was removed from clinical use in February 1970 because it produced nodules in the breast tissues of beagle dogs [...]

- ^ a b Trussell, James (2011). "Contraceptive efficacy". In Hatcher, Robert A.; Trussell, James; Nelson, Anita L.; Cates, Willard Jr.; Kowal, Deborah; Policar, Michael S. (eds.). Contraceptive technology (20th revised ed.). New York: Ardent Media. pp. 779–863. ISBN 978-1-59708-004-0. ISSN 0091-9721. OCLC 781956734. Table 26–1 = Table 3–2 Percentage of women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of typical use and the first year of perfect use of contraception, and the percentage continuing use at the end of the first year. United States. Archived 2013-11-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dhont, Marc (December 2010). "History of oral contraception". The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care. 15 (Suppl 2): S12–18. doi:10.3109/13625187.2010.513071. ISSN 1473-0782. PMID 21091163.

- ^ "Progestin-Only Hormonal Birth Control: Pill and Injection". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Whitaker, Amy K.; Gilliam, Melissa (June 2008). "Contraceptive care for adolescents". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 51 (2): 268–280. doi:10.1097/GRF.0b013e31816d713e. ISSN 1532-5520. PMID 18463458. S2CID 13450620.

- ^ World Health Organization (2015). Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use (5th ed.). Geneva: World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-154915-8.

- ^ a b Hatcher, Robert A. (2018). Contraceptive technology (21st ed.). New York, NY: Ayer Company Publishers, Inc. ISBN 9781732055605.

- ^ "Contraception | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-05-01. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ "Opill OTC Birth Control: Usage, Side Effects & Warnings". Drugs.com. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ Cannon, Joseph G. (2006-01-11). "Chapter 44: Estrogens, Progestins, and the Female Reproductive Tract. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics. 11th Edition Edited by Laurence Brunton, John Lazo, and Keith Parker. McGraw Hill, New York. 2005. xxiii + 2021 pp. 21 × 26 cm. ISBN 0-07-142280-3. $149.95". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 49 (3). doi:10.1021/jm058286b. ISSN 0022-2623.

- ^ a b c Regidor, Pedro-Antonio (2018-10-02). "The clinical relevance of progestogens in hormonal contraception: Present status and future developments". Oncotarget. 9 (77): 34628–34638. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.26015. ISSN 1949-2553. PMC 6195370. PMID 30349654.

- ^ Sitruk-Ware, Regine (2008). "Pharmacological profile of progestins". Maturitas. 61 (1–2): 151–157. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.011. ISSN 0378-5122. PMID 19434887.

- ^ Grimes DA, Lopez LM, O'Brien PA, Raymond EG (2013). "Progestin-only pills for contraception". Cochrane Database Syst Rev (11): CD007541. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007541.pub3. PMID 24226383.

- ^ Hussain SF (2004). "Progestogen-only pills and high blood pressure: is there an association? A literature review". Contraception. 69 (2): 89–97. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2003.09.002. PMID 14759612.

- ^ a b Sylvia K. Rosevear (15 April 2008). Handbook of Gynaecology Management. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 2–. ISBN 978-1-4051-4742-2.

- ^ a b c M.R. Henzl (1978). "Natural and Synthetic Female Sex Hormones". In S.S.C. Yen; R.B. Jaffe (eds.). Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management. W.B. Saunders Co. pp. 421–468. ISBN 978-0-7216-9625-6.

- ^ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products". United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 6 January 2018.

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the (2023-07-13). "FDA Approves First Nonprescription Daily Oral Contraceptive". FDA. Retrieved 2023-07-14.

- ^ American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists' Committee on Clinical Consensus–Gynecology (2022-09-01). "General Approaches to Medical Management of Menstrual Suppression: ACOG Clinical Consensus No. 3". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 140 (3): 528–541. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004899. ISSN 1873-233X. PMID 36356248.

- ^ a b Cooper, Danielle B.; Patel, Preeti; Mahdy, Heba (2023), "Oral Contraceptive Pills", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 28613632, retrieved 2023-11-09

- ^ Trussell, James (May 2011). "Contraceptive failure in the United States". Contraception. 83 (5): 397–404. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. ISSN 1879-0518. PMC 3638209. PMID 21477680.

- ^ a b "Family Planning: A Global Handbook For Providers" (PDF). WHO. 2022. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "Opill Tablets" (PDF).

- ^ Food and Drug Administration (FDA). "SLYND (drosperione), tablets for oral use" (PDF).

- ^ Cox, H. J. E. (1968). "The pre-coital use of mini-dosage progestagens". Journal of Reproduction and Fertility (6): 167–172.

- ^ Bowman, J. A. (1968-12-01). "The effect of norethindrone-mestranol on cervical mucus". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 102 (7): 1039–1040. doi:10.1016/0002-9378(68)90467-5. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 5724391.

- ^ Wollum, Alexandra; Zuniga, Carmela; Blanchard, Kelly; Teal, Stephanie (June 2023). "A commentary on progestin-only pills and the "three-hour window" guidelines: Timing of ingestion and mechanisms of action". Contraception. 122: 109978. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.109978. ISSN 1879-0518. PMID 36801392. S2CID 257068251.

- ^ Wollum, Alexandra; Zuniga, Carmela; Blanchard, Kelly; Teal, Stephanie (June 2023). "A commentary on progestin-only pills and the "three-hour window" guidelines: Timing of ingestion and mechanisms of action". Contraception. 122: 109978. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2023.109978. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 36801392. S2CID 257068251.

- ^ a b Glasier, Anna (March 20, 2015). "Chapter 134. Contraception". In Jameson, J. Larry; De Groot, Leslie J.; de Krester, David; Giudice, Linda C.; Grossman, Ashley; Melmed, Shlomo; Potts, John T. Jr.; Weir, Gordon C. (eds.). Endocrinology: Adult and Pediatric (7th ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier. p. 2306. ISBN 978-0-323-18907-1.

- ^ Mackay, E. V.; Khoo, S. K.; Adam, R. R. (August 1971). "Contraception with a six-monthly injection of progestogen. 2. Effects on cervical mucus secretion and endocrine function". The Australian & New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 11 (3): 156–163. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828x.1971.tb00470.x. ISSN 0004-8666. PMID 5286757. S2CID 38037168.

- ^ Landgren, B. M.; Balogh, A.; Shin, M. W.; Lindberg, M.; Diczfalusy, E. (December 1979). "Hormonal effects of the 300 microgram norethisterone (NET) minipill. 2. Daily gonadotrophin levels in 43 subjects during a pretreatment cycle and during the second month of NET administration". Contraception. 20 (6): 585–605. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(79)80038-4. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 535366.

- ^ Pattman, Richard; Sankar, K. Nathan; Elewad, Babiker; Handy, Pauline; Price, David Ashley, eds. (November 19, 2010). "Chapter 33. Contraception including contraception in HIV infection and infection reduction". Oxford Handbook of Genitourinary Medicine, HIV, and Sexual Health (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-19-957166-6.

Ovulation may be suppressed in 15–40% of cycles by POPs containg levonorgestrel, norethisterone, or etynodiol diacetate, but in 97–99% by those containing desogestrel.

- ^ a b Brunton, Laurence L.; Hilal-Dandan, Randa; Knollmann, Björn C.; Goodman, Louis Sanford; Gilman, Alfred; Gilman, Alfred Goodman, eds. (2018). Goodman & Gilman's The pharmacological basis of therapeutics (Thirteenth ed.). New York: McGraw Hill Education. ISBN 978-1-259-58473-2.

- ^ Porter, Luz S.; Holness, Nola A. (2011). "Breaking the repeat teen pregnancy cycle". Nursing for Women's Health. 15 (5): 368–381. doi:10.1111/j.1751-486X.2011.01661.x. ISSN 1751-486X. PMID 22900650.

- ^ "Lactational Amenorrhea Method". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. March 27, 2023.

- ^ "US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (US MEC) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-09-14. Retrieved 2023-11-14.

- ^ "US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (US MEC) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-03-27. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ^ "US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016 (US MEC) | CDC". www.cdc.gov. 2023-03-27. Retrieved 2023-07-13.

- ^ "Management of Acute Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in Nonpregnant Reproductive-Aged Women". www.acog.org. Retrieved 2023-11-13.

- ^ Munro, Malcolm G.; Critchley, Hilary O. D.; Broder, Michael S.; Fraser, Ian S.; FIGO Working Group on Menstrual Disorders (April 2011). "FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age". International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 113 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2010.11.011. ISSN 1879-3479. PMID 21345435.

- ^ Munro, Malcolm G.; Mainor, Nakia; Basu, Romie; Brisinger, Mikael; Barreda, Lorena (October 2006). "Oral medroxyprogesterone acetate and combination oral contraceptives for acute uterine bleeding: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 108 (4): 924–929. doi:10.1097/01.AOG.0000238343.62063.22. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 17012455. S2CID 26316422.

- ^ Sharara, Fady I.; Kheil, Mira H.; Feki, Anis; Rahman, Sara; Klebanoff, Jordan S.; Ayoubi, Jean Marc; Moawad, Gaby N. (2021-07-30). "Current and Prospective Treatment of Adenomyosis". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (15): 3410. doi:10.3390/jcm10153410. ISSN 2077-0383. PMC 8348135. PMID 34362193.

- ^ Andres, Marina de Paula; Lopes, Livia Alves; Baracat, Edmund Chada; Podgaec, Sergio (2015-09-01). "Dienogest in the treatment of endometriosis: systematic review". Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 292 (3): 523–529. doi:10.1007/s00404-015-3681-6. ISSN 1432-0711. PMID 25749349. S2CID 22168242.

- ^ Mitchell JB, Chetty S, Kathrada F (September 7, 2022). "Progestins in the symptomatic management of endometriosis: a meta-analysis on their effectiveness and safety" (PDF). BMC Women's Health. 22 (1): 52. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01246-4. PMC 10061877. PMID 36997958.

- ^ Weiderpass, E.; Adami, H. O.; Baron, J. A.; Magnusson, C.; Bergström, R.; Lindgren, A.; Correia, N.; Persson, I. (1999-07-07). "Risk of endometrial cancer following estrogen replacement with and without progestins". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 91 (13): 1131–1137. doi:10.1093/jnci/91.13.1131. ISSN 0027-8874. PMID 10393721.

- ^ Belsey, E. M. (August 1988). "Vaginal bleeding patterns among women using one natural and eight hormonal methods of contraception". Contraception. 38 (2): 181–206. doi:10.1016/0010-7824(88)90038-8. ISSN 0010-7824. PMID 2971505.

- ^ Steiner, Mitchell (September 1998). "Campbell's Urology, 7th ed.WalshP.C.: Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.1998. 210 pages.RetikA.B.: Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.1998. 210 pages.VaughanE.D.: Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders Co.1998. 3,426 pages.WeinA.J.: Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. Philadelphia: Isis Medical Media Ltd.1998. 3,426 pages". Journal of Urology. 160 (3 Part 1): 967–968. doi:10.1016/s0022-5347(01)62878-7. ISSN 0022-5347.

- ^ Worly, Brett L.; Gur, Tamar L.; Schaffir, Jonathan (June 2018). "The relationship between progestin hormonal contraception and depression: a systematic review". Contraception. 97 (6): 478–489. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2018.01.010. ISSN 1879-0518. PMID 29496297.

- ^ Tayob, Y.; Adams, J.; Jacobs, H. S.; Guillebaud, J. (October 1985). "Ultrasound demonstration of increased frequency of functional ovarian cysts in women using progestogen-only oral contraception". British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 92 (10): 1003–1009. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1985.tb02994.x. ISSN 0306-5456. PMID 3902074. S2CID 24930690.

- ^ Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (1996). "Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: collaborative reanalysis of individual data on 53,297 women with breast cancer and 100,239 women without breast cancer from 54 epidemiological studies". Lancet. 347 (9017): 1713–27. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(96)90806-5. PMID 8656904. S2CID 36136756.

- ^ Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer (1996). "Breast cancer and hormonal contraceptives: further results". Contraception. 54 (3 Suppl): 1S – 106S. doi:10.1016/s0010-7824(15)30002-0. PMID 8899264.

- ^ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans (1999). "Hormonal contraceptives, progestogens only". Hormonal contraception and post-menopausal hormonal therapy; IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans, Volume 72. Lyon: IARC Press. pp. 339–397. ISBN 92-832-1272-X.

- ^ Chlebowski R, Hendrix S, Langer R, Stefanick M, Gass M, Lane D, Rodabough R, Gilligan M, Cyr M, Thomson C, Khandekar J, Petrovitch H, McTiernan A (2003). "Influence of estrogen plus progestin on breast cancer and mammography in healthy postmenopausal women: the Women's Health Initiative Randomized Trial". JAMA. 289 (24): 3243–53. doi:10.1001/jama.289.24.3243. PMID 12824205.

- ^ a b Zettermark, Sofia; Vicente, Raquel Perez; Merlo, Juan (2018-03-22). "Hormonal contraception increases the risk of psychotropic drug use in adolescent girls but not in adults: A pharmacoepidemiological study on 800 000 Swedish women". PLOS ONE. 13 (3): e0194773. Bibcode:2018PLoSO..1394773Z. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0194773. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5864056. PMID 29566064.

- ^ a b c Skovlund, Charlotte Wessel; Mørch, Lina Steinrud; Kessing, Lars Vedel; Lidegaard, Øjvind (2016-11-01). "Association of Hormonal Contraception With Depression". JAMA Psychiatry. 73 (11): 1154–1162. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.2387. ISSN 2168-6238. PMID 27680324.

- ^ Kulkarni, Jayashri (July 2007). "Depression as a side effect of the contraceptive pill". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 6 (4): 371–374. doi:10.1517/14740338.6.4.371. ISSN 1744-764X. PMID 17688380. S2CID 8836005.

- ^ Martell S, Marini C, Kondas CA, Deutch AB (January 2023). "Psychological side effects of hormonal contraception: a disconnect between patients and providers". Contracept Reprod Med. 8 (1): 9. doi:10.1186/s40834-022-00204-w. PMC 9842494. PMID 36647102.

- ^ Lopez, LM; Ramesh, S; Chen, M; Edelman, A; Otterness, C; Trussell, J; Helmerhorst, FM (28 August 2016). "Progestin-only contraceptives: effects on weight". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (8): CD008815. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008815.pub4. PMC 5034734. PMID 27567593.

- ^ a b Population Reports: Oral contraceptives. Department of Medical and Public Affairs, George Washington Univ. Medical Center. 1975. p. A-64.

Distribution and Use of the Minipill. [...] Progestogen & Dose in mg: d-Norgestrel 0.03. Manufacturer: Schering AG. Brand Names: Microlut, Nordrogest. Where & When First Marketed: Federal Republic of Germany 1971.

- ^ Greenberg (19 February 2016). Exploring the Dimensions of Human Sexuality. Jones & Bartlett Learning. pp. 481–. ISBN 978-1-284-11474-4.

The progestin-only pill was introduced in 1972.

- ^ a b c Amy Whitaker; Melissa Gilliam (27 June 2014). Contraception for Adolescent and Young Adult Women. Springer. pp. 26, 97. ISBN 978-1-4614-6579-9.

- ^ Kathy French (9 November 2009). Sexual Health. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-1-4443-2257-6.

- ^ a b J. Larry Jameson; Leslie J. De Groot (18 May 2010). Endocrinology - E-Book: Adult and Pediatric. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 2424–. ISBN 978-1-4557-1126-0.

In 2002, a POP containing desogestrel 75 ug/day, a dose sufficient to inhibit ovulation in almost every cycle, was introduced in Europe.51

- ^ Commissioner, Office of the (2023-07-13). "FDA Approves First Nonprescription Daily Oral Contraceptive". FDA. Retrieved 2023-07-13.