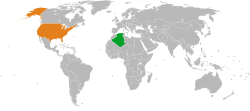

Algeria–United States relations

| |

Algeria |

United States |

|---|---|

| Diplomatic mission | |

| Algerian Embassy, Washington, D.C. | United States Embassy, Algiers |

| Envoy | |

| Mohammed Haneche[1] | Elizabeth Moore Aubin |

In July 2001, President Abdelaziz Bouteflika became the first Algerian President to visit the White House since 1985.[2][3] This visit was followed by a second meeting in November 2001. Also, President Bouteflika's participation at the June 2004 G8 Sea Island Summit, was an indication of the growing relationship between the United States and Algeria.[2][3] Since the September 11 attacks in the United States, contacts in key areas of mutual concern, including law enforcement and counter-terrorism cooperation, have intensified.[3] Algeria publicly condemned the terrorist attacks on the United States and has been strongly supportive of the Global War on Terrorism.[3] The United States and Algeria consult closely on key international and regional issues.[3] The pace and scope of senior-level visits has accelerated.[3]

History

[edit]Precolonial Period

[edit]The European maritime powers paid the tribute demanded by the rulers of the pirate states of North Africa (Algiers, Tunis, Tripoli) to prevent attacks on their cargo by privateers. No longer covered by English tribute payments after the American Revolution, US merchant ships were seized and sailors enslaved in the years following independence. In 1794, the US Congress allocated funds for the construction of warships to counter the threat of piracy in the Mediterranean. Despite the naval preparations, the United States concluded a treaty with the dey of Algiers in 1797, guaranteeing the payment of tribute amounting to US$10 million over a period of twelve years in exchange for a promise that Algerian privateers would not disturb the US fleets. Ransom and tribute payments to pirate states amounted to 20 per cent of the US government's annual revenues in 1804.

On 5 September 1795, when the two countries signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship between the United States and the Regency of Algiers,[4] a few years after the Regency's official recognition of the independence of the young American republic (1783), Algeria was among the first countries to recognise the independence of the United States.

Being desirous of establishing and cultivating Peace and Harmony between our Nation and the Dey, Regency, and People of Algiers, I have appointed David Humphreys, one of our distinguished Citizens, a Commissioner Plenipotentiary, giving him full Power to negotiate and conclude a Treaty of Amity and Commerce with you. And I pray you to give full credit to whatever shall be delivered to you on the part of the United States, by him, and particularly when he shall assure you of our sincere desire to be in Peace and Friendship with you, and your People. And I pray God to give you Health and Happiness. Done at Philadelphia this Twenty first day of March 1793, and in the seventeenth Year of the Independence of these United States.

— George Washington, Philadelphia, 21 March 1793[5]

Colonial Period

[edit]The Napoleonic wars of the early 19th century diverted the attention of the maritime powers from suppressing what they considered piracy.[6] But when peace was restored to Europe in 1815, Algiers found itself at war with Spain, the Netherlands, Prussia, Denmark, Russia, and Naples.[6] In March of that year, in what became the Second Barbary War, the United States Congress authorized naval action against the Barbary States, the Turkish Muslim states Algiers, Tunis, and Tripoli.[6] Commodore Stephen Decatur was dispatched with a squadron of ten warships to ensure the safety of United States shipping in the Mediterranean and to force an end to the payment of tribute.[6] After capturing several corsairs and their crews, Decatur sailed into the harbor of Algiers, threatened the city with his guns, and concluded a favorable treaty in which the dey agreed to discontinue demands for tribute, pay reparations for damage to United States property, release United States prisoners without ransom, and prohibit further interference with United States trade by Algerian corsairs.[6] No sooner had Decatur set off for Tunis to enforce a similar agreement than the dey repudiated the treaty.[6] The next year, an Anglo-Dutch fleet, commanded by British admiral Viscount Exmouth, delivered a nine-hour bombardment of Algiers.[6] The attack immobilized many of the dey's corsairs and obtained from him a second treaty that reaffirmed the conditions imposed by Decatur.[6] In addition, the dey agreed to end the practice of enslaving Christians.[6]

The Eisenhower administration gave military equipment to France during the Algerian War of Independence.[7] However, France did not trust U.S. intentions in the Maghreb area, especially since the U.S. had friendly relations with Morocco and Tunisia after the two countries had won their independence.[7] The United States tried to balance the situation with Algeria without alienating France. The FLN tried to appeal to America to support its independence.[7]

Present day

[edit]Post-independence

[edit]Algeria and the United States have a complicated relationship that has improved politically and economically. When John F. Kennedy was still a senator, he spoke in support of Algerian independence to The New York Times on July 2, 1957.[8] During his presidency, Kennedy congratulated Algeria after it had won its independence from the French in 1962.[9] Prime Minister Ben Bella visited President Kennedy on October 15, 1962, one day before the Cuban Missile Crisis started.[10] However, Algeria cut off diplomacy in 1967 because of the Arab-Israeli War, since it supported the Arab countries while the United States was on the Israeli side.[10] In 1971 Natural Gas Corporation from El Paso and Algerian Sonatrach signed an 25 years long agreement on export of 15 billion cubic meters of natural gas starting from 1974.[11] President Nixon was able to reestablish relations and President Boumédiène visited the United States on April 11, 1974.[12]

During the Iranian hostage crisis, Algeria mediated negotiation between the United States and Iran.[13] The Algiers Declarations was signed on January 19, 1981.[14] Iran released 52 American hostages on January 20, 1981.[15]

9/11

[edit]

After the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, Algeria was one of the first countries to offer its support to the US and continued to play a key role in the struggle against terrorism. It has been working since then closely with the United States to eliminate transnational terrorism. The United States made Algeria a "pivotal state" in the war on terror.[16] One of the major agreements between the two countries allowed the U.S. to use an airfield in Southern Algeria to deploy surveillance aircraft.[16] After this, the U.S. has been more neutral on Algerian government political and civil rights violations.[16] Algeria persists in leading the battle against terrorism in Africa.[17]

Mid-2000s–present

[edit]

In August 2005, then-Chairman of the United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, Senator Richard G. Lugar, led a delegation to oversee the release of the remaining 404 Moroccan prisoners of war held by the Polisario Front in Algeria.[18][3] Their release removed a longstanding bilateral obstacle between Algeria and Morocco.[3]

In April 2006, then-Foreign Minister Mohammed Bedjaoui met with U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice.[19][3]

As of 2007, the official U.S. presence was Algeria is expanding following over a decade of limited staffing, reflecting the general improvement in the security environment.[3] Between 2004 and 2007, the U.S. Embassy moved toward more normal operations and as of 2007 provided most embassy services to the American and Algerian communities.[3]

President Bouteflika welcomed President Barack Obama's election and said he would be glad to work with him to further cooperation between the two countries.[20] The intensity of the cooperation between Algeria and the United States is illustrated by the number and frequency of senior-level visits made by civilian and military officials of both countries. Relations between Algeria and the United States have entered a new, dynamic phase. While characterized by close collaboration on regional and international issues of mutual interest, ties between both countries are also defined by the significance and level of their cooperation in the economic area. The number of US corporations already active or exploring business ventures in Algeria has increased significantly over the past few years, reflecting growing confidence in the Algerian market and institutions. Senior officers of the Algerian Army, including its Chief of Staff and the Secretary General of the Ministry of National Defense, have made official visits in the United States. Algeria has hosted US Navy and Coast Guard visits and took part with the United States in NATO joint naval exercises. The increasing level of cooperation and exchanges between Algeria and the United States has generated bilateral agreements in numerous areas, including the Agreement on Science and Technology Cooperation, signed in January 2006. An agreement was concluded recently between the Government of Algeria and the Government of the United States, entering into force on November 1, 2009, pursuant to which the maximum validity for several categories of visas granted to Algerian citizens coming to the United States was extended to 24 months. A mutual legal assistance treaty and a Customs Cooperation Agreement will also be signed soon.[21]

On 20 January 2013, the United States Department of State issued a travel warning to United States citizens for the country of Algeria in response to the In Aménas hostage crisis.[22]

Algeria has stated that it is dedicated to sustaining its good relations with the U.S. in July 2016.[23]

In 2020, the United States recognized Moroccan sovereignty over the disputed territory of Western Sahara in exchange for Moroccan normalization of relations with Israel. Algeria said the U.S. decision to recognize Moroccan sovereignty over Western Sahara "has no legal effect because it contradicts U.N. resolutions, especially U.N. Security Council resolutions on Western Sahara".[24]

In February 2024, President Joe Biden appointed Joshua Harris, the U.S. Under Secretary of State for North African Affairs, as the new U.S. Ambassador to Algeria, replacing Ambassador Elizabeth Moore Aubin, who had held the position since February 9, 2022, according to a press release issued on the official White House website.[25]

Algerian leaders' visits to the United States

[edit]

Algerian leaders have visited the United States a total of seven times. The first visit took place on October 14–15, 1962 when Prime Minister Ben Bella stopped by Washington D.C.[2] President Boumediene privately visited Washington and met with Nixon on April 11, 1974.[2] President Chedli Bendjedid came for a State Visit from April 16–22, 1985.[2] President Abdelaziz Bouteflika visited July 11–14, 2001, November 5, 2001, and June 9–10, 2004.[2] Prime Minister Abdelmalek Sellal attended the U.S.-Africa Leaders Summit on August 5–6, 2016.[2] In December 2022, former Prime Minister Aymen Benabderrahmane attended the 2022 U.S - Africa summit.

Trade

[edit]

In 2006, U.S. direct investment in Algeria totaled $5.3 billion, mostly in the petroleum sector, which U.S. companies dominate.[3] American companies are active in the banking and finance sectors, as well as in services, pharmaceuticals, medical facilities, telecommunications, aviation, seawater desalination, energy production, and information technology.[3] Algeria is the United States' 3rd-largest market in the Middle East/North African region.[3] U.S. exports to Algeria totaled $1.2 billion in 2005, an increase of more than 50% since 2003.[3] U.S. imports from Algeria grew from $4.7 billion in 2002 to $10.8 billion in 2005, primarily in oil and liquefied natural gas.[3] In March 2004, President Bush designated Algeria a beneficiary country for duty-free treatment under the Generalized System of Preferences.[3]

In July 2001, the United States and Algeria signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement, which established common principles on which the economic relationship is founded and forms a platform for negotiating a bilateral investment treaty and a free-trade agreement.[3] The two governments meet on a regular basis in order to discuss trade and investment policies and opportunities, as well as to enhance their economic relationship.[3] Within the framework of the U.S.-North African Economic Partnership, the United States provided about $1 million in technical assistance to Algeria in 2003.[3] This program supported and encouraged Algeria's economic reform program and included support for World Trade Organization accession negotiations, debt management, and improving the investment climate.[3] In 2003, the U.S.-North African Economic Partnership programs were rolled over into Middle East Partnership Initiative activities, which provide funding for political and economic development programs in Algeria.[3]

Military

[edit]

As of 2007, cooperation between the Algerian and U.S. militaries continued to grow.[3] Exchanges between both sides are frequent, and Algeria has hosted senior U.S. military officials.[3] In May 2005, the United States and Algeria conducted their first formal joint military dialogue in Washington, DC; the second joint military dialogue took place in Algiers in November 2006.[3] The NATO Supreme Allied Commander, Europe and Commander, U.S. European Command, General James L. Jones visited Algeria in June and August 2005, and then-Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld visited Algeria in February 2006.[3] The United States and Algeria have also conducted bilateral naval and Special Forces exercises, and Algeria has hosted U.S. Navy and Coast Guard ship visits.[3] The United States has a modest International Military Education and Training Program ($824,000 in FY 2006) for training Algerian military personnel in the United States, and Algeria participates in the Trans-Sahara Counter-Terrorism Partnership.[3]

The Secretary of State hosted a Strategic Dialogue with the Algerian Foreign Minister in April 2015.[26] Additionally, the Deputy Secretary of State paid a visit to Algeria in July 2016.[26]

Education and culture

[edit]

The first U.S.A and Algerian collaboration in the education field started in 1959 when the Institute of International Education cooperated with the National Student Association in 1959 to bring Algerian students to study in our universities.[citation needed] After the independence, it established the Institute of Electrical Engineering and Electronics, the only institute in North Africa that follows an American model way of teaching.[citation needed] The United States has implemented modest university linkages programs and has placed two English-Language Fellows, the first since 1993, with the Ministry of Education to assist in the development of English as a second language courses at the Ben Aknoune Training Center.[3] In 2006, Algeria was again the recipient of a grant under the Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation, which provided $106,110 to restore the El Pacha Mosque in Oran.[3] Algeria also received an $80,000 grant to fund microscholarships to design and implement an American English-language program for Algerian high school students in four major cities.[3]

Initial funding through the Middle East Partnership Initiative has been allocated to support the work of Algeria's developing civil society through programming that provides training to journalists, businesspersons, legislators, Internet regulators, and the heads of leading nongovernmental organizations.[3] Additional funding through the U.S. Department of State's Human Rights and Democracy Fund will assist civil society groups focusing on the issues of the disappeared, and Islam and democracy.[3]

Embassies

[edit]The U.S. Embassy in Algeria is at 4 Chemin Cheikh Bachir El-Ibrahimi, Algiers. The Algerian Embassy in the United States is at 2118 Kalorama Road, Washington D.C.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ait Seddik, Baha eddine (August 21, 2022). "Agrément à la nomination du nouvel ambassadeur d'Algérie auprès des Etats Unis d'Amérique". Algeria Press Service (in French).

- ^ a b c d e f g "Algeria – Visits by Foreign Leaders – Department History – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag "Background Note: Algeria". U.S. Department of State. October 2007. Archived from the original on February 12, 2008.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ "Avalon Project - The Barbary Treaties 1786-1816 - Treaty of Peace and Amity, Signed at Algiers September 5, 1795". avalon.law.yale.edu. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ "Founders Online: From George Washington to the Dey of Algiers, 21 March 1793". founders.archives.gov. Retrieved 2022-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Metz, Helen Chapin, ed. (1993). Algeria: a country study. Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 22. OCLC 44230753.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ^ a b c Zoubir, Yahia H. (1 January 1995). "The United States, the Soviet Union and Decolonization of the Maghreb, 1945–62". Middle Eastern Studies. 31 (1): 58–84. doi:10.1080/00263209508701041. JSTOR 4283699.

- ^ Rakove, Robert B. (2013-01-01). Kennedy, Johnson, and the Nonaligned World. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-00290-6.

- ^ "Statement on Algerian independence, 3 July 1962 – John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum". www.jfklibrary.org. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b "John F. Kennedy: Remarks of Welcome to Prime Minister Ben Bella of Algeria on the South Lawn at the White House". www.presidency.ucsb.edu. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Milutin Tomanović, ed. (1972). Hronika međunarodnih događaja 1971 [The Chronicle of International Events in 1971] (in Serbo-Croatian). Belgrade: Institute of International Politics and Economics. p. 2551.

- ^ "BOUMEDIENE TO SEE NIXON ON THURSDAY". The New York Times. 1974-04-09. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-03-22.

- ^ "Crisis-Managing U.S.-Iran Relations". Council on Foreign Relations. Archived from the original on 2017-03-25. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Christopher, Warren; Most, Richard (2007). "The Iranian Hostage Crisis and the Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal: Implications for International Dispute Resolution and Diplomacy". Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal. 7: 10.

- ^ Network, The Learning (20 January 2012). "Jan. 20, 1981 | Iran Releases American Hostages as Reagan Takes Office". The Learning Network. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ a b c Bangura, Abdul K. (2007-01-01). Stakes in Africa-United States Relations: Proposals for Equitable Partnership. iUniverse. ISBN 978-0-595-45197-5.

- ^ Zoubir, Yahia (2015). "Algeria's Roles in the OAU/African Union: From National Liberation Promoter to Leader in the Global War on Terrorism". Mediterranean Politics. 20: 55–75. doi:10.1080/13629395.2014.921470. S2CID 153891638.

- ^ "Moroccan POWs ask help punishing captors". The Washington Times. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ "Photo: Secretary Rice With Algerian Foreign Minister Mohamed Bedjaoui". 2001-2009.state.gov. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "Algerian president congratulates Obama after re-election – China.org.cn". china.org.cn. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ Embassy of Algeria to the United States of America Archived 2018-01-22 at the Wayback Machine.Tuesday May 25. 2010 (accessed May 26, 2010), by Abdallah Baali

- ^ "US warns Americans of travel risks in Algeria". Fox News. 20 January 2013.

- ^ LLC, Ask For Media. "Embassy of Algerie in the United-States of America | Algerian Consular Affairs, Economic Affairs, Foreign Affairs, Algeria Us relations". www.algerianembassy.org. Archived from the original on 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

- ^ "Algeria rejects Trump's stance on Western Sahara". Reuters. December 12, 2020.

- ^ The White House (2024-02-29). "President Biden Announces Key Nominees". The White House. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ^ a b "Algeria". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 2017-03-24.

Further reading

[edit]- Berhail, Wafa, and Fatima Maameri. "The role of Algeria in the Iran Hostage Crisis, 1979-1981." (2017). Online

- Christelow, Allan. Algerians without Borders: The Making of a Global Frontier Society (U Press of Florida, 2012).

- Farhi, Abderraouf, and Billel Fillali. "The Economic and political interplay in the American Algerian relations in the 1960 and 1970." (2016) online

- Ghettas, Mohammed Lakhdar. Algeria and the Cold War: International Relations and the Struggle for Autonomy (Bloomsbury, 2017).

- Miller, Olivia. "Algerian Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs, (3rd ed., vol. 1, Gale, 2014), pp. 87–96. online

- Papadopoulou, Nikoletta. "The narrative’s ‘general truth’: Authenticity and the mediation of violence in Barbary captivity narratives." European Journal of American Culture 36.3 (2017): 209–223.