Metronidazole

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Flagyl |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a689011 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth, topical, rectal, intravenous, vaginal |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 80% (by mouth), 60–80% (rectal), 20–25% (vaginal)[7][8][9] |

| Protein binding | 20%[7][8] |

| Metabolism | Liver[7][8] |

| Metabolites | Hydroxymetronidazole |

| Elimination half-life | 8 hours[7][8] |

| Excretion | Urine (77%), faeces (14%)[7][8] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| NIAID ChemDB | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.489 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C6H9N3O3 |

| Molar mass | 171.156 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| Melting point | 159 to 163 °C (318 to 325 °F) |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Metronidazole, sold under the brand name Flagyl among others, is an antibiotic and antiprotozoal medication.[10] It is used either alone or with other antibiotics to treat pelvic inflammatory disease, endocarditis, and bacterial vaginosis.[10] It is effective for dracunculiasis, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and amebiasis.[10] It is an option for a first episode of mild-to-moderate Clostridioides difficile colitis if vancomycin or fidaxomicin is unavailable.[10][11] Metronidazole is available orally (by mouth), as a cream or gel, and by slow intravenous infusion (injection into a vein).[10][4]

Common side effects include nausea, a metallic taste, loss of appetite, and headaches.[10] Occasionally seizures or allergies to the medication may occur.[10] Some state that metronidazole should not be used in early pregnancy, while others state doses for trichomoniasis are safe.[1][weasel words] Metronidazole is generally considered compatible with breastfeeding.[1][12]

Metronidazole began to be commercially used in 1960 in France.[13] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[14] It is available in most areas of the world.[15] In 2022, it was the 133rd most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 4 million prescriptions.[16][17]

Medical uses

[edit]

Metronidazole has activity against some protozoans and most anaerobic bacteria (both Gram-negative and Gram-positive classes) but not the aerobic bacteria.[18][19]

Metronidazole is primarily used to treat: bacterial vaginosis, pelvic inflammatory disease (along with other antibacterials like ceftriaxone), pseudomembranous colitis, aspiration pneumonia, rosacea (topical), fungating wounds (topical), intra-abdominal infections, lung abscess, periodontal disease, amoebiasis, oral infections, giardiasis, trichomoniasis, and infections caused by susceptible anaerobic organisms such as Bacteroides, Fusobacterium, Clostridium, Peptostreptococcus, and Prevotella species.[20] It is also often used to eradicate Helicobacter pylori along with other drugs and to prevent infection in people recovering from surgery.[20]

Metronidazole is bitter and so the liquid suspension contains metronidazole benzoate. This may require hydrolysis in the gastrointestinal tract and some sources speculate that it may be unsuitable in people with diarrhea or feeding-tubes in the duodenum or jejunum.[21][22]

Bacterial vaginosis

[edit]Drugs of choice for the treatment of bacterial vaginosis include metronidazole and clindamycin.[23]

An effective treatment option for mixed infectious vaginitis is a combination of clotrimazole and metronidazole.[24]

Trichomoniasis

[edit]The 5-nitroimidazole drugs (metronidazole and tinidazole) are the mainstay of treatment for infection with Trichomonas vaginalis. Treatment for both the infected patient and the patient's sexual partner is recommended, even if asymptomatic. Therapy other than 5-nitroimidazole drugs is also an option, but cure rates are much lower.[25]

Giardiasis

[edit]Oral metronidazole is a treatment option for giardiasis, however, the increasing incidence of nitroimidazole resistance is leading to the increased use of other compound classes.[26]

Dracunculus

[edit]In the case of Dracunculus medinensis (Guinea worm), metronidazole merely facilitates worm extraction rather than killing the worm.[10]

C. difficile colitis

[edit]Initial antibiotic therapy for less-severe Clostridioides difficile infection colitis (pseudomembranous colitis) consists of metronidazole, vancomycin, or fidaxomicin by mouth.[11] In 2017, the IDSA generally recommended vancomycin and fidaxomicin over metronidazole.[11] Vancomycin by mouth has been shown to be more effective in treating people with severe C. difficile colitis.[27]

E. histolytica

[edit]Entamoeba histolytica invasive amebiasis is treated with metronidazole for eradication, in combination with diloxanide to prevent recurrence.[28] Although it is generally a standard treatment it is associated with some side effects.[29]

Preterm births

[edit]Metronidazole has also been used in women to prevent preterm birth associated with bacterial vaginosis, amongst other risk factors including the presence of cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin (fFN). Metronidazole was ineffective in preventing preterm delivery in high-risk pregnant women (selected by history and a positive fFN test) and, conversely, the incidence of preterm delivery was found to be higher in women treated with metronidazole.[30]

Hypoxic radiosensitizer

[edit]In addition to its anti-biotic properties, attempts were also made to use a possible radiation-sensitizing effect of metronidazole in the context of radiation therapy against hypoxic tumors.[31] However, the neurotoxic side effects occurring at the required dosages have prevented the widespread use of metronidazole as an adjuvant agent in radiation therapy.[32] However, other nitroimidazoles derived from metronidazole such as nimorazole with reduced electron affinity showed less serious neuronal side effects and have found their way into radio-onological practice for head and neck tumors in some countries.[33]

Perioral dermatitis

[edit]Canadian Family Physician has recommended topical metronidazole as a third-line treatment for the perioral dermatitis either along with or without oral tetracycline or oral erythromycin as first and second line treatment respectively.[34]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common adverse drug reactions (≥1% of those treated with the drug) associated with systemic metronidazole therapy include: nausea, diarrhea, weight loss, abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, dizziness, and metallic taste in the mouth. Intravenous administration is commonly associated with thrombophlebitis. Infrequent adverse effects include: hypersensitivity reactions (rash, itch, flushing, fever), headache, dizziness, vomiting, glossitis, stomatitis, dark urine, and paraesthesia.[20] High doses and long-term systemic treatment with metronidazole are associated with the development of leucopenia, neutropenia, increased risk of peripheral neuropathy, and central nervous system toxicity.[20] Common adverse drug reaction associated with topical metronidazole therapy include local redness, dryness and skin irritation; and eye watering (if applied near eyes).[20][35] Metronidazole has been associated with cancer in animal studies.[36][failed verification] In rare cases, it can also cause temporary hearing loss that reverses after cessation of the treatment.[37][38]

Some evidence from studies in rats indicates the possibility it may contribute to serotonin syndrome, although no case reports documenting this have been published to date.[39][40]

Mutagenesis and carcinogenesis

[edit]In 2016 metronidazole was listed by the U.S. National Toxicology Program (NTP) as reasonably anticipated to be a human carcinogen.[41] Although some of the testing methods have been questioned, oral exposure has been shown to cause cancer in experimental animals and has also demonstrated some mutagenic effects in bacterial cultures.[41][42] The relationship between exposure to metronidazole and human cancer is unclear.[41][43] One study [44] found an excess in lung cancer among women (even after adjusting for smoking), while other studies [45][46][47] found either no increased risk, or a statistically insignificant risk.[41][48] Metronidazole is listed as a possible carcinogen according to the World Health Organization (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC).[49] A study in those with Crohn's disease also found chromosomal abnormalities in circulating lymphocytes in people treated with metronidazole.[42]

Stevens–Johnson syndrome

[edit]Metronidazole alone rarely causes Stevens–Johnson syndrome, but is reported to occur at high rates when combined with mebendazole.[50]

Neurotoxicity

[edit]Several studies in the human[51] and animal models have recorded the neurotoxicity of metronidazole. One possible mechanism underlying this toxicity is that metronidazole may interference with postsynaptic central monoaminergic neurotransmission and immunomodulation.[52] Additionally other research suggests that the role of nitric oxide isoforms and inflammatory cytokines may also play a role.[53]

Drug interactions

[edit]Alcohol

[edit]Consuming alcohol while taking metronidazole has been suspected in case reports to cause a disulfiram-like reaction with effects that can include nausea, vomiting, flushing of the skin, tachycardia, and shortness of breath.[54] People are often advised not to drink alcohol during systemic metronidazole therapy and for at least 48 hours after completion of treatment.[20] However, some studies call into question the mechanism of the interaction of alcohol and metronidazole,[55][56][57] and a possible central toxic serotonin reaction for the alcohol intolerance is suggested.[39] Metronidazole is also generally thought to inhibit the liver metabolism of propylene glycol (found in some foods, medicines, and in many electronic cigarette e-liquids), thus propylene glycol may potentially have similar interaction effects with metronidazole.[medical citation needed]

Other drug interactions

[edit]Metronidazole is a moderate inhibitor of the enzyme CYP2C9 belonging to the cytochrome P450 family. As a result, metronidazole may interact with medications metabolized by this enzyme.[58][59][60] Examples of such medications are lomitapide and warfarin, to name a few.[7]

Pharmacology

[edit]

Mechanism of action

[edit]Metronidazole is of the nitroimidazole class. It is a prodrug that inhibits nucleic acid synthesis by forming nitroso radicals, which disrupt the DNA of microbial cells.[7][61] Metronidazole activates by receiving an electron from the reduced ferredoxin produced by pyruvate synthase (PFOR) in anaerobic organisms, equivalent to pyruvate dehydrogenase in aerobic organisms, thus turning into a highly reactive radical anion. After the radical loses the electron to its target, it recycles back to the unactivated form of metronidazole, ready to be activated again. [62]

This function only occurs when metronidazole is partially reduced, and because oxygen competes with metronidazole for the electron, this reduction requires a local environment with low oxygen concentration that usually happens only in anaerobic bacteria and protozoans. Therefore, it has relatively little effect upon human cells or aerobic bacteria.[63] Elevation of oxygen level in the organism will decrease its rate of generating the activated metronidazole, but also increase the rate of recycling back to the unactivated metronidazole. [62]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]

Oral metronidazole is approximately 80% bioavailable via the gut and peak blood plasma concentrations occur after one to two hours. Food may slow down absorption but does not diminish it. Of the circulating substance, about 20% is bound to plasma proteins. It penetrates well into tissues, the cerebrospinal fluid, the amniotic fluid and breast milk, as well as into abscess cavities.[61]

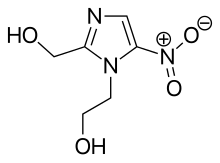

About 60% of the metronidazole is metabolized by oxidation to the main metabolite hydroxymetronidazole and a carboxylic acid derivative, and by glucuronidation. The metabolites show antibiotic and antiprotozoal activity in vitro.[61] Metronidazole and its metabolites are mainly excreted via the kidneys (77%) and to a lesser extent via the faeces (14%).[7][8] The biological half-life of metronidazole in healthy adults is eight hours, in infants during the first two months of their lives about 23 hours, and in premature babies up to 100 hours.[61]

The biological activity of hydroxymetronidazole is 30% to 65%, and the elimination half-life is longer than that of the parent compound.[64] The serum half-life of hydroxymetronidazole after suppository was 10 hours, 19 hours after intravenous infusion, and 11 hours after a tablet.[65]

Resistance

[edit]Resistance in parasites is found in T. vaginilis, and G. lamblia, but not E. histolytica, and two major methods are observed. The first method involves an impaired oxygen scavenging capability that increase the local concentration of oxygen, leading to the decreased activation and increased recycling of metronidazole. The second method is associated with lowered levels of pyruvate synthase and ferredoxin, the latter due to the lowered transcription of the ferredoxin gene. Strains employing the second method will still respond to a higher dosage of metronidazole.[62]

Resistance in bacteria is documented in Bacteriodes spp. that resistant to nitroimidazoles including metronidazole. In the resistant strains, 5-nitroimidazole reductase is identified as the culprit that actively reduces metronidazole to inactive forms. Currently eleven types are identified which are encoded by nimA through nimK respectively. The gene is encoded either in the chromosome or the episome.[62][66][67]

Other mechanisms may include reduced drug activation, efflux pumps, altered redox potential and biofilm formation. In the recent years it is observed that the resistance to metronidazole is increasingly common, complicating its clinical effectiveness.[68][69][70][clarification needed]

History

[edit]The drug was initially developed by Rhône-Poulenc in the 1950s[71] and licensed to G.D. Searle.[72] Searle was acquired by Pfizer in 2003.[73] The original patent expired in 1982, but evergreening reformulation occurred thereafter.[74]

Brand name

[edit]In India, it is sold under the brand name Metrogyl and Flagyl.[75] In Bangladesh, it is available as Amodis, Amotrex, Dirozyl, Filmet, Flagyl, Flamyd, Metra, Metrodol, Metryl, etc.[76] In Pakistan, it is sold under the brand name of Flagyl and Metrozine.[citation needed] In the United States it is sold under the brand name Noritate.[77]

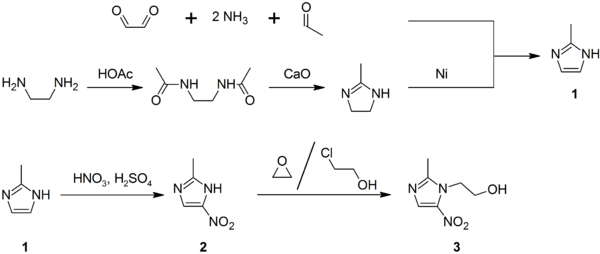

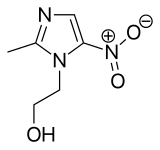

Synthesis

[edit]2-Methylimidazole (1) may be prepared via the Debus-Radziszewski imidazole synthesis, or from ethylenediamine and acetic acid, followed by treatment with lime, then Raney nickel. 2-Methylimidazole is nitrated to give 2-methyl-4(5)-nitroimidazole (2), which is in turn alkylated with ethylene oxide or 2-chloroethanol to give metronidazole (3):[78][79][80]

Research

[edit]Metronidazole is researched for its anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties. Studies have shown that metronidazole can decrease the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitric oxide by activated immune cells, such as macrophages and neutrophils. Metronidazole's immunomodulatory properties are thought to be related to its ability to decrease the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), a transcription factor that regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including chemokines, and adhesion molecules. Cytokines are small proteins that are secreted by immune cells and play a key role in the immune response.[81] Chemokines are a type of cytokines that act as chemoattractants, meaning they attract and guide immune cells to specific sites in the body where they are needed.[82] Cell adhesion molecules play an important role in the immune response by facilitating the interaction between immune cells and other cells in the body, such as endothelial cells, which form the lining of blood vessels.[83] By inhibiting NF-κB activation, metronidazole can reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF-alpha, IL-6, and IL-1β.[84]

Metronidazole has been studied in various immunological disorders, including inflammatory bowel disease, periodontitis, and rosacea. In these conditions, metronidazole has been suspected to have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects that could be beneficial in the treatment of these conditions.[85] Despite the success in treating rosacea with metronidazole,[86][87][88][89][90] the exact mechanism of why metronidazole in rosacea is efficient is not precisely known, i.e., which properties of metronidazole help treat rosacea: antibacterial or immunomodulatory or both, or other mechanism is involved.[91][92] Increased ROS production in rosacea is thought to contribute to the inflammatory process and skin damage, so metronidazole's ability to decrease ROS may explain the mechanism of action in this disease, but this remains speculation.[93][94]

Metronidazole is also researched as a potential anti-inflammatory agent in periodontitis treatment.[95]

Veterinary use

[edit]Metronidazole is used to treat infections of Giardia in dogs, cats, and other companion animals, but it does not reliably clear infection with this organism and is being supplanted by fenbendazole for this purpose in dogs and cats.[96] It is also used for the management of chronic inflammatory bowel disease, gastrointestinal infections, periodontal disease, and systemic infections in cats and dogs.[97][98] Another common usage is the treatment of systemic and/or gastrointestinal clostridial infections in horses. Metronidazole is used in the aquarium hobby to treat ornamental fish and as a broad-spectrum treatment for bacterial and protozoan infections in reptiles and amphibians. In general, the veterinary community may use metronidazole for any potentially susceptible anaerobic infection. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) suggests it only be used when necessary because it has been shown to be carcinogenic in mice and rats, as well as to prevent antimicrobial resistance.[99][100]

The appropriate dosage of metronidazole varies based on the animal species, the condition being treated and the specific formulation of the product.[101]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Metronidazole Use During Pregnancy". www.drugs.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2017. Retrieved 1 January 2017.

- ^ "FDA-sourced list of all drugs with black box warnings (Use Download Full Results and View Query links.)". nctr-crs.fda.gov. FDA. Retrieved 22 October 2023.

- ^ "METRONIDAMED (Medsurge Pharma Pty LTD) | Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA)". Archived from the original on 15 September 2024. Retrieved 15 September 2024.

- ^ a b "Metronidazole injection, solution". DailyMed. 16 January 2023. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Metronidazole tablet". DailyMed. 30 January 2023. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ "Metronidazole Vaginal Gel, 0.75%- metronidazole gel". DailyMed. 17 June 2023. Archived from the original on 6 September 2023. Retrieved 5 July 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Flagyl, Flagyl ER (metronidazole) dosing, indications, interactions, adverse effects, and more". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Archived from the original on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ a b c d e f Brayfield A, ed. (14 January 2014). "Metronidazole". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 3 April 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Brayfield A, ed. (2017). Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference (39th ed.). London: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-309-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Metronidazole". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on 6 September 2015. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b c McDonald LC, Gerding DN, Johnson S, Bakken JS, Carroll KC, Coffin SE, et al. (March 2018). "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Clostridium difficile Infection in Adults and Children: 2017 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA) and Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America (SHEA)". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 66 (7): e1 – e48. doi:10.1093/cid/cix1085. PMC 6018983. PMID 29462280.

- ^ "Safety in Lactation: Metronidazole and tinidazole". SPS - Specialist Pharmacy Service. Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 22 February 2020.

- ^ Corey EJ (2013). Drug discovery practices, processes, and perspectives. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-118-35446-9. Archived from the original on 8 September 2017.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ Schmid G (28 July 2003). "Trichomoniasis treatment in women". Archived from the original on 1 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 30 August 2024. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ "Metronidazole Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on 13 April 2020. Retrieved 30 August 2024.

- ^ Freeman CD, Klutman NE, Lamp KC (November 1997). "Metronidazole. A therapeutic review and update". Drugs. 54 (5): 679–708. doi:10.2165/00003495-199754050-00003. PMID 9360057.

- ^ Löfmark S, Edlund C, Nord CE (January 2010). "Metronidazole is still the drug of choice for treatment of anaerobic infections". Clin Infect Dis. 50 (Suppl 1): S16–23. doi:10.1086/647939. PMID 20067388.

- ^ a b c d e f Rossi S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ Geoghegan O, Eades C, Moore LS, Gilchrist M (9 February 2017). "Clostridium difficile: diagnosis and treatment update". The Pharmaceutical Journal. Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Archived from the original on 7 March 2019. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- ^ Dickman A (2012). Drugs in Palliative Care. OUP Oxford. p. 355. ISBN 978-0-19-163610-3. Archived from the original on 25 June 2022. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ^ Joesoef MR, Schmid GP, Hillier SL (January 1999). "Bacterial vaginosis: review of treatment options and potential clinical indications for therapy". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 28 (Suppl 1): S57 – S65. doi:10.1086/514725. PMID 10028110.

- ^ Huang Y, Shen C, Shen Y, Cui H (January 2024). "Assessing the Efficacy of Clotrimazole and Metronidazole Combined Treatment in Vaginitis: A Meta-Analysis". Altern Ther Health Med. 30 (1): 186–191. PMID 37773671.

- ^ duBouchet L, Spence MR, Rein MF, Danzig MR, McCormack WM (March 1997). "Multicenter comparison of clotrimazole vaginal tablets, oral metronidazole, and vaginal suppositories containing sulfanilamide, aminacrine hydrochloride, and allantoin in the treatment of symptomatic trichomoniasis". Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 24 (3): 156–160. doi:10.1097/00007435-199703000-00006. PMID 9132982. S2CID 6617019.

- ^ Leitsch D (September 2015). "Drug Resistance in the Microaerophilic Parasite Giardia lamblia". Current Tropical Medicine Reports. 2 (3): 128–135. doi:10.1007/s40475-015-0051-1. PMC 4523694. PMID 26258002.

- ^ Zar FA, Bakkanagari SR, Moorthi KM, Davis MB (August 2007). "A comparison of vancomycin and metronidazole for the treatment of Clostridium difficile-associated diarrhea, stratified by disease severity". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 45 (3): 302–307. doi:10.1086/519265. PMID 17599306.

- ^ Ryan KJ, Ahmad N, Alspaugh JA, Drew WL, Lagunoff M, Pottinger P, et al. (12 January 2018). Sherris medical microbiolog (Seventh ed.). New York: McGraw Hill LLC. ISBN 978-1-259-85981-6. OCLC 1004770160.

- ^ Rawat A, Singh P, Jyoti A, Kaushik S, Srivastava VK (August 2020). "Averting transmission: A pivotal target to manage amoebiasis". Chemical Biology & Drug Design. 96 (2): 731–744. doi:10.1111/cbdd.13699. PMID 32356312. S2CID 218475533.

- ^ Shennan A, Crawshaw S, Briley A, Hawken J, Seed P, Jones G, et al. (January 2006). "A randomised controlled trial of metronidazole for the prevention of preterm birth in women positive for cervicovaginal fetal fibronectin: the PREMET Study". BJOG. 113 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00788.x. PMID 16398774. S2CID 11366650.

- ^ Nori D, Cain JM, Hilaris BS, Jones WB, Lewis JL (August 1983). "Metronidazole as a radiosensitizer and high-dose radiation in advanced vulvovaginal malignancies, a pilot study". Gynecologic Oncology. 16 (1): 117–28. doi:10.1016/0090-8258(83)90017-3. PMID 6884824.

- ^ Sarna JR, Furtado S, Brownell AK (November 2013). "Neurologic complications of metronidazole". The Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 40 (6): 768–776. doi:10.1017/s0317167100015870. PMID 24257215.

- ^ Overgaard J, Hansen HS, Overgaard M, Bastholt L, Berthelsen A, Specht L, et al. (February 1998). "A randomized double-blind phase III study of nimorazole as a hypoxic radiosensitizer of primary radiotherapy in supraglottic larynx and pharynx carcinoma. Results of the Danish Head and Neck Cancer Study (DAHANCA) Protocol 5-85". Radiotherapy and Oncology. 46 (2): 135–46. doi:10.1016/s0167-8140(97)00220-x. PMID 9510041.

- ^ Cheung MJ, Taher M, Lauzon GJ (April 2005). "Acneiform facial eruptions: a problem for young women". Canadian Family Physician. 51 (4): 527–533. PMC 1472951. PMID 15856972.

- ^ Side Effects

- ^ "Flagyl metronidazole tablets label" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2015.

- ^ Iqbal SM, Murthy JG, Banerjee PK, Vishwanathan KA (April 1999). "Metronidazole ototoxicity--report of two cases". The Journal of Laryngology and Otology. 113 (4): 355–357. doi:10.1017/s0022215100143968. PMID 10474673. S2CID 45989669.

- ^ Lawford R, Sorrell TC (August 1994). "Amebic abscess of the spleen complicated by metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity: case report". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 19 (2): 346–348. doi:10.1093/clinids/19.2.346. PMID 7986915.

- ^ a b Karamanakos PN, Pappas P, Boumba VA, Thomas C, Malamas M, Vougiouklakis T, et al. (2007). "Pharmaceutical agents known to produce disulfiram-like reaction: effects on hepatic ethanol metabolism and brain monoamines". International Journal of Toxicology. 26 (5): 423–432. doi:10.1080/10915810701583010. PMID 17963129. S2CID 41230661.

- ^ Karamanakos PN (November 2008). "The possibility of serotonin syndrome brought about by the use of metronidazole". Minerva Anestesiologica. 74 (11): 679. PMID 18971895.

- ^ a b c d National Toxicology Program (2016). "Metronidazole" (PDF). Report on Carcinogens (Fourteenth ed.). National Toxicology Program (NTP). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 February 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- ^ a b "Metrogyl Metronidazole Product Information" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Alphapharm Pty Limited. 8 May 2013. Archived from the original on 9 September 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2014.

- ^ Bendesky A, Menéndez D, Ostrosky-Wegman P (June 2002). "Is metronidazole carcinogenic?". Mutation Research. 511 (2): 133–144. Bibcode:2002MRRMR.511..133B. doi:10.1016/S1383-5742(02)00007-8. PMID 12052431.

- ^ Beard CM, Noller KL, O'Fallon WM, Kurland LT, Dahlin DC (February 1988). "Cancer after exposure to metronidazole". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 63 (2): 147–153. doi:10.1016/s0025-6196(12)64947-7. PMID 3339906.

- ^ "Metronidazole (IARC Summary & Evaluation, Supplement7, 1987)". INCHEM2. 3 March 1998. Archived from the original on 4 August 2020. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Thapa PB, Whitlock JA, Brockman Worrell KG, Gideon P, Mitchel EF, Roberson P, et al. (October 1998). "Prenatal exposure to metronidazole and risk of childhood cancer: a retrospective cohort study of children younger than 5 years". Cancer. 83 (7): 1461–1468. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981001)83:7<1461::aid-cncr25>3.0.co;2-1. PMID 9762949.

- ^ Friedman GD, Jiang SF, Udaltsova N, Quesenberry CP, Chan J, Habel LA (November 2009). "Epidemiologic evaluation of pharmaceuticals with limited evidence of carcinogenicity". International Journal of Cancer. 125 (9): 2173–2178. doi:10.1002/ijc.24545. PMC 2759691. PMID 19585498.

- ^ "Flagyl 375 U.S. Prescribing Information" (PDF). Pfizer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 August 2008.

- ^ "Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–124". International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). 8 July 2019. Archived from the original on 6 September 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- ^ Chen KT, Twu SJ, Chang HJ, Lin RS (March 2003). "Outbreak of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with mebendazole and metronidazole use among Filipino laborers in Taiwan". American Journal of Public Health. 93 (3): 489–492. doi:10.2105/ajph.93.3.489. PMC 1447769. PMID 12604501.

- ^ Yamamoto T, Abe K, Anjiki H, Ishii T, Kuyama Y (August 2012). "Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity developed in liver cirrhosis". Journal of Clinical Medicine Research. 4 (4): 295–298. doi:10.4021/jocmr893w. PMC 3409628. PMID 22870180.

- ^ Bariweni MW, Kamenebali I, Denyefa JB (15 April 2024). "Metronidazole-induced neurotoxicity: Possible central serotonergic and noradrenergic system involvement". Medical and Pharmaceutical Journal. 3 (1): 22–34. doi:10.55940/medphar202474. Archived from the original on 26 July 2024. Retrieved 26 July 2024.

- ^ Chaturvedi S, Malik MY, Rashid M, Singh S, Tiwari V, Gupta P, et al. (July 2020). "Mechanistic exploration of quercetin against metronidazole induced neurotoxicity in rats: Possible role of nitric oxide isoforms and inflammatory cytokines". Neurotoxicology. 79: 1–10. Bibcode:2020NeuTx..79....1C. doi:10.1016/j.neuro.2020.03.002. PMID 32151614.

- ^ Cina SJ, Russell RA, Conradi SE (December 1996). "Sudden death due to metronidazole/ethanol interaction". The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology. 17 (4): 343–346. doi:10.1097/00000433-199612000-00013. PMID 8947362.

- ^ Gupta NK, Woodley CL, Fried R (October 1970). "Effect of metronidazole on liver alcohol dehydrogenase". Biochemical Pharmacology. 19 (10): 2805–2808. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(70)90108-5. PMID 4320226.

- ^

Williams CS, Woodcock KR (February 2000). "Do ethanol and metronidazole interact to produce a disulfiram-like reaction?". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 34 (2): 255–257. doi:10.1345/aph.19118. PMID 10676835. S2CID 21151432.

the authors of all the reports presumed the metronidazole-ethanol reaction to be an established pharmacologic fact. None provided evidence that could justify their conclusions

- ^ Visapää JP, Tillonen JS, Kaihovaara PS, Salaspuro MP (June 2002). "Lack of disulfiram-like reaction with metronidazole and ethanol". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 36 (6): 971–974. doi:10.1345/1542-6270(2002)036<0971:lodlrw>2.0.co;2. PMID 12022894.

- ^ Flockhart DA (2007). "Drug Interactions: Cytochrome P450 Drug Interaction Table". Indiana University School of Medicine. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007. Retrieved 4 January 2022.

- ^ Kudo T, Endo Y, Taguchi R, Yatsu M, Ito K (May 2015). "Metronidazole reduces the expression of cytochrome P450 enzymes in HepaRG cells and cryopreserved human hepatocytes". Xenobiotica; the Fate of Foreign Compounds in Biological Systems. 45 (5): 413–419. doi:10.3109/00498254.2014.990948. PMID 25470432. S2CID 26910995.

- ^ Tirkkonen T, Heikkilä P, Huupponen R, Laine K (October 2010). "Potential CYP2C9-mediated drug-drug interactions in hospitalized type 2 diabetes mellitus patients treated with the sulphonylureas glibenclamide, glimepiride or glipizide". Journal of Internal Medicine. 268 (4): 359–366. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2010.02257.x. PMID 20698928. S2CID 45449460.

- ^ a b c d Haberfeld H, ed. (2020). Austria-Codex (in German). Vienna: Österreichischer Apothekerverlag. Anaerobex-Filmtabletten.

- ^ a b c d Brunton LL (2011). Goodman & Gilman's the pharmacological basis of therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill medical. p. 1429. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ Eisenstein BI, Schaechter M (2007). "DNA and Chromosome Mechanics". In Schaechter M, Engleberg NC, DiRita VJ, Dermody T (eds.). Schaechter's Mechanisms of Microbial Disease. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-7817-5342-5.

- ^ Lamp KC, Freeman CD, Klutman NE, Lacy MK (May 1999). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the nitroimidazole antimicrobials". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 36 (5): 353–373. doi:10.2165/00003088-199936050-00004. PMID 10384859. S2CID 37891515.

- ^ Bergan T, Leinebo O, Blom-Hagen T, Salvesen B (1984). "Pharmacokinetics and bioavailability of metronidazole after tablets, suppositories and intravenous administration". Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. Supplement. 91: 45–60. PMID 6588489.

- ^ Alauzet C, Aujoulat F, Lozniewski A, Marchandin H (February 2019) [2019-02]. "A sequence database analysis of 5-nitroimidazole reductase and related proteins to expand knowledge on enzymes responsible for metronidazole inactivation". Anaerobe. 55: 29–34. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.10.005. PMID 30315962.

- ^ Leiros HK, Kozielski-Stuhrmann S, Kapp U, Terradot L, Leonard GA, McSweeney SM (December 2004). "Structural basis of 5-nitroimidazole antibiotic resistance: the crystal structure of NimA from Deinococcus radiodurans". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 279 (53): 55840–55849. doi:10.1074/jbc.M408044200. PMID 15492014.

- ^ Krakovka S, Ribacke U, Miyamoto Y, Eckmann L, Svärd S (11 January 2022). "Characterization of Metronidazole-Resistant Giardia intestinalis Lines by Comparative Transcriptomics and Proteomics". Frontiers in Microbiology. 13: 834008. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.834008. PMC 8866875. PMID 35222342.

- ^ Alauzet C, Lozniewski A, Marchandin H (February 2019). "Metronidazole resistance and nim genes in anaerobes: A review". Anaerobe. 55: 40–53. doi:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2018.10.004. PMID 30316817. S2CID 52983319.

- ^ Smith A (March 2018). "Metronidazole resistance: a hidden epidemic?" (PDF). British Dental Journal. 224 (6): 403–404. doi:10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.221. PMID 29545544. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 November 2023. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Quirke V (29 December 2014). "Targeting the American market for medicines, ca. 1950s-1970s: ICI and Rhône-Poulenc compared". Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 88 (4): 654–696. doi:10.1353/bhm.2014.0075. PMC 4335572. PMID 25557515.

- ^ "G.D. SEARLE & CO. v. COMM | 88 T.C. 252 (1987) | 8otc2521326 | Leagle.com". Leagle. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ "2003:Pfizer and Pharmacia Merger". Pfizer. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ^ Dickson S (July 2019). "Effect of Evergreened Reformulations on Medicaid Expenditures and Patient Access from 2008 to 2016". Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy. 25 (7): 780–792. doi:10.18553/jmcp.2019.18366. PMC 10398228. PMID 30799664.

- ^ "Metrogyl ER". Medical Dialogues. Archived from the original on 17 April 2021. Retrieved 1 March 2021.

- ^ "Metronidazole Brands". Medex. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 24 November 2021.

- ^ "Noritate (Metronidazole): Uses, Dosage, Side Effects, Interactions, Warning". RxList. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ^ Ebel K, Koehler H, Gamer AO, Jäckh R. "Imidazole and Derivatives". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_661. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Actor P, Chow AW, Dutko FJ, McKinlay MA. "Chemotherapeutics". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.a06_173. ISBN 978-3527306732.

- ^ Kraft MY, Kochergin PM, Tsyganova AM, Shlikhunova VS (1989). "Synthesis of metronidazole from ethylenediamine". Pharmaceutical Chemistry Journal. 23 (10): 861–863. doi:10.1007/BF00764821. S2CID 38187002.

- ^ Opal SM, DePalo VA (April 2000). "Anti-inflammatory cytokines". Chest. 117 (4): 1162–72. doi:10.1378/chest.117.4.1162. PMID 10767254. S2CID 2267250.

- ^ van der Vorst EP, Döring Y, Weber C (November 2015). "Chemokines". Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 35 (11): e52–6. doi:10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306359. PMID 26490276.

- ^ Elangbam CS, Qualls CW, Dahlgren RR (January 1997). "Cell adhesion molecules--update". Vet Pathol. 34 (1): 61–73. doi:10.1177/030098589703400113. PMID 9150551. S2CID 46474241.

- ^ Rizzo A, Paolillo R, Guida L, Annunziata M, Bevilacqua N, Tufano MA (July 2010). "Effect of metronidazole and modulation of cytokine production on human periodontal ligament cells". Int Immunopharmacol. 10 (7): 744–50. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2010.04.004. PMID 20399284.

- ^ Gonçalves-Santos E, Caldas I, Fernandes V, Franco L, Pelozo M, Feltrim F, et al. (August 2023). "Pharmacological potential of new metronidazole/eugenol/dihydroeugenol hybrids against Trypanosoma cruzi in vitro and in vivo". Int Immunopharmacol. 121: 110416. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2023.110416. PMID 37295025. S2CID 259126738.

- ^ King S, Campbell J, Rowe R, Daly ML, Moncrieff G, Maybury C (October 2023). "A systematic review to evaluate the efficacy of azelaic acid in the management of acne, rosacea, melasma and skin aging". J Cosmet Dermatol. 22 (10): 2650–2662. doi:10.1111/jocd.15923. PMID 37550898. S2CID 260701677.

- ^ Kazemi S, Hawkes JE (June 2023). "Ocular rosacea associated with transient monocular vision loss: resolution with oral metronidazole" (PDF). Dermatol Online J. 29 (3). doi:10.5070/D329361439. PMID 37591279. S2CID 263745257. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2024. Retrieved 2 February 2024.

- ^ Kim JS, Seo BH, Cha DR, Suh HS, Choi YS (December 2022). "Maintenance of Remission after Oral Metronidazole Add-on Therapy in Rosacea Treatment: A Retrospective, Comparative Study". Ann Dermatol. 34 (6): 451–460. doi:10.5021/ad.22.093. PMC 9763916. PMID 36478427.

- ^ Yamasaki K, Miyachi Y (December 2022). "Perspectives on rosacea patient characteristics and quality of life using baseline data from a phase 3 clinical study conducted in Japan". J Dermatol. 49 (12): 1221–1227. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.16596. PMC 10092295. PMID 36177741.

- ^ Dall'Oglio F, Nasca MR, Gerbino C, Micali G (November 2022). "Advances in pharmacotherapy for rosacea: what is the current state of the art?". Expert Opin Pharmacother. 23 (16): 1845–1854. doi:10.1080/14656566.2022.2142907. PMID 36330970. S2CID 253301872.

- ^ Seidler Stangova P, Dusek O, Klimova A, Heissigerova J, Kucera T, Svozilkova P (2019). "Metronidazole Attenuates the Intensity of Inflammation in Experimental Autoimmune Uveitis". Folia Biol (Praha). 65 (5–6): 265–274. doi:10.14712/fb2019065050265. PMID 32362310. S2CID 218491876.

- ^ Fararjeh M, Mohammad MK, Bustanji Y, Alkhatib H, Abdalla S (February 2008). "Evaluation of immunosuppression induced by metronidazole in Balb/c mice and human peripheral blood lymphocytes". Int Immunopharmacol. 8 (2): 341–50. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2007.10.018. PMID 18182250.

- ^ Jones D (September 2004). "Reactive oxygen species and rosacea". Cutis. 74 (3 Suppl): 17–20, 32–4. PMID 15499754.

- ^ Narayanan S, Hünerbein A, Getie M, Jäckel A, Neubert RH (August 2007). "Scavenging properties of metronidazole on free oxygen radicals in a skin lipid model system". J Pharm Pharmacol. 59 (8): 1125–30. doi:10.1211/jpp.59.8.0010. PMID 17725855. S2CID 19772010.

- ^ Suárez LJ, Arce RM, Gonçalves C, Furquim CP, Santos NC, Retamal-Valdes B, et al. (April 2024). "Metronidazole may display anti-inflammatory features in periodontitis treatment: A scoping review". Mol Oral Microbiol. 39 (4): 240–259. doi:10.1111/omi.12459. PMID 38613247.

- ^ Barr SC, Bowman DD, Heller RL (July 1994). "Efficacy of fenbendazole against giardiasis in dogs". American Journal of Veterinary Research. 55 (7): 988–990. doi:10.2460/ajvr.1994.55.07.988. PMID 7978640.

- ^ Hoskins JD (1 October 2001). "Advances in managing inflammatory bowel disease". DVM Newsmagazine. Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2013.

- ^ "METRONIDAZOLE (Veterinary—Systemic)" (PDF). Retrieved 4 July 2024.

- ^ Plumb DC (2008). Veterinary Drug Handbook (6th ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-8138-2056-9.

- ^ "Metronidazole". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013.

- ^ "Metronidazole For Dogs: Safe Dosages And Uses". Forbes. 11 July 2023. Retrieved 4 July 2024.

External links

[edit]- "Metronidazole and Tinidazole". Merck manuals.