The Blair Witch Project

| The Blair Witch Project | |

|---|---|

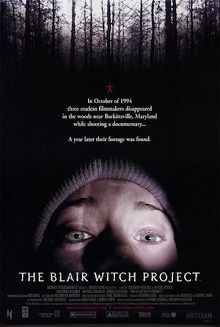

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Neal Fredericks |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Tony Cora |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 81 minutes[2] |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $200,000–750,000[3] |

| Box office | $248.6 million[4] |

The Blair Witch Project is a 1999 American psychological horror film written, directed, and edited by Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez. One of the most successful independent films of all time, it is a "found footage" mockumentary in which three students (Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams, and Joshua Leonard) hike into the Black Hills near Burkittsville, Maryland, to shoot a documentary about a local myth known as the Blair Witch.

Myrick and Sánchez conceived of a fictional legend of the Blair Witch in 1993. They developed a 35-page screenplay with the dialogue to be improvised. A casting call advertisement on Backstage magazine was prepared by the directors; Donahue, Williams, and Leonard were cast. The film entered production in October 1997, with the principal photography lasting eight days. Most of the filming was done on the Greenway Trail along Seneca Creek in Montgomery County, Maryland. About 20 hours of footage was shot, which was edited down to 82 minutes. Shot on an original budget of $35,000–60,000, the film had a final cost of $200,000–750,000 after post-production and marketing.

When The Blair Witch Project premiered at the Sundance Film Festival at midnight on January 23, 1999, its promotional marketing campaign listed the actors as either "missing" or "deceased". Due to its successful Sundance run, Artisan Entertainment bought the film's distribution rights for $1.1 million. The film had a limited release on July 14 of the same year, before expanding to a wider release starting on July 30. While the film received critical acclaim, audience reception was polarized.

The Blair Witch Project was a sleeper hit. It grossed nearly $250 million worldwide and is consistently listed as one of the scariest movies of all time. Despite the success, the three main actors had reportedly lived in poverty. In 2000, they sued Artisan Entertainment claiming unfair compensation, eventually reaching a $300,000 settlement. The Blair Witch Project launched a media franchise, which includes two sequels (Book of Shadows and Blair Witch), novels, comic books, and video games. It revived the found-footage technique and influenced similarly successful horror films such as Paranormal Activity (2007), REC (2007) and Cloverfield (2008).

Plot

[edit]The film purports to be footage found in the discarded cameras of three young filmmakers who had gone missing.

In October 1994, film students Heather, Mike, and Josh set out to produce a documentary about the mythical Blair Witch. They travel to Burkittsville, Maryland, and interview residents about the myth. Locals tell them of Rustin Parr, a hermit who lived deep in the forest and abducted seven children in 1941; he murdered them all in his basement, killing them in pairs while having one stand in a corner, facing the wall. The students explore the forest in north Burkittsville to research the myth. They meet two fishermen, one of whom warns them that the forest is cursed. He tells them of a young child named Robin Weaver, who went missing in 1888; when she returned three days later, she talked about an old woman whose feet never touched the ground. The students hike to Coffin Rock, where five men were found ritualistically slaughtered in the 19th century; their corpses later disappeared.

They camp for the night and, the next day, find an old graveyard with seven small cairns, one of which Josh accidentally knocks over. That night, they hear the sound of sticks snapping. The following day, they try to hike back to the car but cannot find it before dark and make camp. They again hear sticks snapping. In the morning, they find three cairns built beside their tent. Heather learns her map is missing; Mike reveals he kicked it into a creek out of frustration, which provokes a fight between the trio as they realize they are lost. They head south, using Heather's compass, and discover stick figures hanging from trees. They again hear mysterious sounds that night, including children laughing. After an unknown force or person shakes the tent, they hide in the forest until dawn.

Upon returning to their tent, they find their possessions have been rifled, and Josh's equipment is covered with slime. They come across a river identical to the one they crossed earlier and realize they have been walking in circles. Josh vanishes the next morning, and Heather and Mike try vainly to find him. That night, they hear Josh's agonized cries but are unable to find him. They theorize that his yells are a fabrication by the Blair Witch to draw them out of their camp.

Heather discovers a bundle of twigs tied with fabric from Josh's shirt the next day. Upon opening the bundle, she finds a blood-soaked scrap of his shirt containing a tongue, a finger, some teeth and hair. Although distraught, she does not tell Mike. That night, she records herself apologizing to her, Mike's, and Josh's families, taking responsibility for their predicament. She admits that something evil is haunting them and will ultimately take them.

That night, they hear Josh calling out to them and follow his voice to the abandoned ruins of the house of Rustin Parr, featuring children's bloody handprints on one of the walls. Trying to locate Josh, they go to the basement, where an unseen villain assaults Mike, causing him to drop his camera. Heather enters the basement yelling, and her camera captures Mike standing in a corner facing the wall. Heather calls out to him, but he does not react. The unseen villain assaults Heather, causing her to scream and drop her camera. In an eerie silence, the camera continues to work, albeit on its side. The sideways image holds for a few seconds, and then the film concludes with a cut to black.

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]Development of The Blair Witch Project began in 1993.[5] While film students at the University of Central Florida, Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez were inspired to make the film after realizing that they found documentaries on paranormal phenomena scarier than traditional horror films. The two decided to create a film that combined the styles of both. In order to produce the project, they, along with Gregg Hale, Robin Cowie and Michael Monello, started Haxan Films. The namesake for the production company is Benjamin Christensen's 1922 silent documentary horror film Häxan (English: Witchcraft Through the Ages).[6]

Myrick and Sánchez developed a 35-page screenplay for their fictional film, intending dialogue to be improvised. The directors placed a casting call advertisement in Backstage in June 1996, asking for actors with strong improvisational abilities.[7][8] The informal improvisational audition process narrowed the pool of 2,000 actors.[9][10]

According to Heather Donahue, auditions for the film were held at Musical Theater Works in New York City. The advertisement said a "completely improvised feature film" would be shot in a "wooded location". Donahue said that during the audition, Myrick and Sánchez posed her the question: "You've served seven years of a nine-year sentence. Why should we let you out on parole?" to which she had to respond.[7] Joshua Leonard said he was cast due to his knowledge of how to run a camera, as no omniscient camera was used to film the scenes.[11]

Pre-production began on October 5, 1997, and Michael Monello became a co-producer.[12][8] In developing the mythology behind the film, the creators used many inspirations. For instance, several character names are near-anagrams: Elly Kedward (The Blair Witch) is Edward Kelley, a 16th-century mystic, and Rustin Parr, the fictional 1940s child-murderer, began as an anagram for Rasputin.[13] The Blair Witch is said to be, according to legend, the ghost of Elly Kedward, a woman banished from the Blair Township (latter-day Burkittsville) for witchcraft in 1785.

The directors incorporated that part of the legend, along with allusions to the Salem witch trials and Arthur Miller's 1953 play The Crucible, to play on the themes of injustice done to those who were classified as witches.[14]

The directors also cited influences such as the television series In Search of..., and horror documentary films Chariots of the Gods and The Legend of Boggy Creek.[9][10] Other influences included commercially successful horror films such as The Shining, Alien, The Omen, and Jaws—the latter film being their major influence, as the film hides the witch from the viewer for its entirety, increasing the suspense of the unknown.[5][9]

In talks with investors, the directors presented an eight-minute documentary, along with newspapers and news footage.[15] The documentary was aired on the television series Split Screen hosted by John Pierson on August 6, 1998.[9][8]

Filming

[edit]Principal photography began on October 23, 1997, in Maryland and lasted eight days, overseen by cinematographer Neal Fredericks, who provided a CP-16 film camera.[6][12][16] The three actors shot all the footage shown in the film, except for one interview about Rustin Parr's murders.[17] The "found footage" was shot with a Hi8 camcorder.[16][18] Most of the film was shot in Seneca Creek State Park in Montgomery County, Maryland. A few scenes were filmed in the historic town of Burkittsville.[citation needed] Some of the townspeople interviewed in the film were not actors, and some were planted actors, unknown to the main cast.[16] Donahue had never operated a camera before and spent two days in a "crash course". Donahue said she modeled her character after a director she had once worked with, noting her character's "self-assuredness" when everything went as planned, and confusion during crisis.[19]

The actors were given clues as to their next location through messages hidden inside 35 mm film cans left in milk crates they found with Global Positioning Satellite systems. They were given individual instructions to use to help improvise the action of the day.[7][16][20] Teeth were obtained from a Maryland dentist for use as human remains in the film.[7] Influenced by producer Gregg Hale's memories of his military training, in which "enemy soldiers" would hunt a trainee through wild terrain for three days, the directors moved the characters a long way during the day, harassing them by night, and depriving them of food.[15]

Instead of using fictional names, all three actors used their real names in the film, something Donahue has regretted doing. She revealed in 2014 that she had trouble finding new roles because of it.[21]

According to the filmmakers' commentary, the unseen figure that Donahue is shouting about as she is running away from the tent is the film's art director Ricardo Moreno, who was wearing white long-johns, white stockings, and white pantyhose pulled over his head.[22][23] The final scenes were filmed at the historic Griggs House, a 150-year-old building located in the Patapsco Valley State Park near Granite, Maryland.[24] Filming concluded on October 31, Halloween.[25]

In an interview with Entertainment Weekly, Sánchez revealed that when principal photography first wrapped, approximately $20,000 to $25,000 had been spent.[20] Richard Corliss of Time magazine reported a $35,000 estimated budget.[26] By September 2016, The Blair Witch Project has been officially budgeted at $60,000.[29]

Sánchez says that the ending with Mike standing in the corner was invented days before it was shot.[30]

Post-production

[edit]After filming, the 20 hours of raw footage had to be cut down to 81 minutes; the editing process took more than eight months. The directors screened the first cut in small film festivals in order to get feedback and make changes that would ensure that it appealed to as large an audience as possible.[5] Originally, it was hoped that the film would make it on to cable television, and the directors did not anticipate a wide release.[5] The final version was submitted to Sundance Film Festival.[31]

After becoming a surprise hit at Sundance, during its midnight premiere on January 25, 1999, Artisan Entertainment bought the distribution rights for $1.1 million.[5] Prior to that, Artisan had wanted to change the film's original ending, as the test audience, although scared, were confused by it. Donahue screams in terror and finds Michael C. Williams facing a corner in the basement before her camera falls to the ground.[32] Although the ending was not changed, an additional interview was added to the first section of the film to contextualize the ending.[30][17] The directors and Williams traveled back to Maryland and shot four alternate endings,[33] one of which employed bloody elements. They also shot additional interviews, at least one of which (the Parr backstory) making it into the wide-release cut.[30] This footage would be the only segment of film not shot by the main actors.[17] Ultimately, the directors and Williams decided to keep the original ending. Myrick said: "What makes us fearful is something that's out of the ordinary, unexplained. The first ending kept the audience off balance; it challenged our real world conventions and that's what really made it scary".[32]

Post-production fees increased the cost of the film to several hundred thousand dollars before its Sundance debut and, after marketing costs, the total cost of the film has been estimated as ranging between $500,000 and $750,000.[20][34]

Compensation controversy

[edit]In 2024, Donahue, Leonard and Williams detailed to Variety how, according to their claims, they had never been adequately compensated by Artisan Entertainment/Lionsgate for their work in the original movie. They recall living in poverty after the success, being barred from saying so publicly, and having few options since they had no "proper union or legal representation when the film was made." In summer 1999 they received a bump in the low five figures. In October 2000, with the release of Blair Witch 2 impending, Donahue convinced Williams and Leonard to sue Artisan. They reached a $300,000 settlement for each of them. The three actors claim that they had no clear knowledge that the entire movie would be composed of their found footage, and that they had not given much thought to the clause that allowed production to use their real identities. This led to subsequent discussions with Lionsgate regarding the usage of their likenesses. Despite the conflicts, Donahue, Leonard and Williams have called themselves proud of their work in the movie.[35]

Marketing

[edit]

The Blair Witch Project is thought to be the first widely released film marketed primarily by the Internet. Kevin Foxe became executive producer in May 1998 and brought in Clein & Walker, a public relations firm. The film's official website launched in June, featuring faux police reports as well as "newsreel-style" interviews, and fielding questions about the "missing" students.[8] These augmented the film's found footage device to spark debates across the Internet over whether the film was a real-life documentary or a work of fiction.[36][37] Some of the footage was screened during the Florida Film Festival in June.[8] During screenings, the filmmakers made advertising efforts to promulgate the events in the film as factual, including the distribution of flyers at festivals such as Sundance, asking viewers to come forward with any information about the "missing" students.[38][39] The campaign tactic was that viewers were being told, through missing persons posters, that the characters were missing while researching in the woods for the mythical Blair Witch.[40] The IMDb page also listed the actors as "missing, presumed dead" in the first year of the film's availability.[41] The film's website contains materials of actors posing as police and investigators giving testimony about their casework, and shared childhood photos of the actors to add a sense of realism.[42] By August 1999, the website had received 160 million hits.[34]

After the Sundance screening, Artisan acquired the film and a distribution strategy was created and implemented by Steven Rothenberg.[43][44] The film's trailer was leaked on the website Ain't It Cool News on April 2, 1999, and the film was screened at 40 colleges in the United States to build word-of-mouth.[8] A third, 40-second, trailer was shown before Star Wars: Episode I – The Phantom Menace in June.[8]

USA Today reported that The Blair Witch Project was the first film to go viral despite having been produced before many of the technologies that facilitate such phenomena existed.[45]

Fictional legend

[edit]The backstory for the film is a legend fabricated by Sánchez and Myrick which is detailed in the Curse of the Blair Witch, a mockumentary broadcast on the Sci-Fi Channel on July 12, 1999.[46][8] Sánchez and Myrick also maintain a website which adds further details to the legend.[47]

The legend describes the killings and disappearances of some of the residents of Blair, Maryland (a fictitious town on the site of Burkittsville, Maryland) from the 18th to 20th centuries. Residents blamed these occurrences on the ghost of Elly Kedward, a Blair resident accused of practicing witchcraft in 1785 and sentenced to death by exposure. The Curse of the Blair Witch presents the legend as real, complete with manufactured newspaper articles, newsreels, television news reports, and staged interviews.[46]

Release

[edit]The Blair Witch Project premiered as a Midnight Screening on Saturday, January 23, 1999, at the Sundance Film Festival, and opened Wednesday, July 14, at the Angelika Film Center in New York City before expanding to 25 cities at the weekend. It expanded nationwide on July 30.[8]

Television broadcast

[edit]For its basic cable premiere in October 2001 on FX, two deleted scenes were reinserted during the end credits of the film. Neither deleted scene has ever been officially released.[48]

Home media

[edit]The Blair Witch Project was released on VHS and DVD on October 22, 1999[49][50] by Artisan, presented in a 1.33:1 windowboxed aspect ratio and Dolby Digital 2.0 audio. Special features include the documentary Curse of the Blair Witch, a five-minute Newly Discovered Footage, audio commentary, production notes, and cast and crew biographies. The audio commentary presents directors Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez, and producers Rob Cowie, Mike Monello and Gregg Hale, in which they discuss the film's production. The Curse of the Blair Witch feature provides an in-depth look inside the creation of the film.[51][52] More than $15 million was spent to market the home video release of the film.[53]

The film's Blu-ray version was released on October 5, 2010, by Lionsgate.[54] Best Buy and Lionsgate had an exclusive release of the Blu-ray made available on August 29 the same year.[55] Additionally, in 2024, British label Second Sight Films completed a restored version of the film from new digital transfers of the video & film elements, approved by the producers and directors, which was released in the UK on November 11 that year.[56]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The film earned $1.5 million from 27 theaters in its opening weekend, with a per-screen average of $56,002.[4] The film expanded nationwide in its third weekend and grossed $29.2 million from 1,101 locations, placing at number two in the United States box office, surpassing the science fiction horror film Deep Blue Sea but behind Runaway Bride.[57] The film expanded further to 2,142 theaters and again finished in second place with a gross of $24.3 million in its fourth weekend, behind another horror film The Sixth Sense.[58] The film dropped out of the top-ten list in its 10th weekend and by the end of its theatrical run, the film grossed $140.5 million in the US and Canada and grossed $108.1 million in other territories, for a worldwide gross of $248.6 million (over 4,000 times its original budget).[4][32] The Blair Witch Project was the 10th highest-grossing film in the US in 1999,[59] and has earned the reputation of becoming a sleeper hit.[60] In Italy it set an opening weekend record for a US film.[61]

Because the filming was done by the actors using hand-held cameras, much of the footage is shaky, especially the final sequence in which a character is running down a set of stairs with the camera. Some audience members experienced motion sickness and even vomited as a result.[62]

Critical response

[edit]At a time when digital techniques can show us almost anything, The Blair Witch Project is a reminder that what really scares us is the stuff we can't see. The noise in the dark is almost always scarier than what makes the noise in the dark.

The Blair Witch Project drew acclaim from critics.[64] The review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes gives the film a score of 86% based on 165 reviews from critics, with an average rating of 7.70/10. The website's consensus reads: "Full of creepy campfire scares, mock-doc The Blair Witch Project keeps audiences in the dark about its titular villain, proving once more that imagination can be as scary as anything onscreen."[65] On Metacritic the film received a weighted average of 80 out of 100 based on 33 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[66] Audience reception to the film, though, remains divided;[67] Those polled by CinemaScore gave it an average grade of "C+" on a scale of A+ to F.[68]

The Blair Witch Project's found-footage technique received near-universal praise. Although this was not the first film to use it, the independent film was declared a milestone in film history due to its critical and box office success.[73] Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film four stars, and called it "an extraordinarily effective horror film".[63] Peter Travers of Rolling Stone called it "a groundbreaker in fright that reinvents scary for the new millennium".[74] Todd McCarthy of Variety said: "An intensely imaginative piece of conceptual filmmaking that also delivers the goods as a dread-drenched horror movie, The Blair Witch Project puts a clever modern twist on the universal fear of the dark and things that go bump in the night".[75] Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly gave a grade of "B": "As a horror picture, the film may not be much more than a cheeky game, a novelty with the cool, blurry look of an avant-garde artifact. But as a manifestation of multimedia synergy, it's pretty spooky".[76]

Some critics were less enthusiastic. Andrew Sarris of The New York Observer deemed it "overrated", as well as a rendition of "the ultimate triumph of the Sundance scam: Make a heartless home movie, get enough critics to blurb in near unison 'scary' and watch the suckers flock to be fleeced".[77] A critic from The Christian Science Monitor said that while the film's concept and scares were innovative, he felt it could have just been shot "as a 30-minute short ... since its shaky camera work and fuzzy images get monotonous after a while, and there's not much room for character development within the very limited plot".[78] R. L. Schaffer of IGN scored it two out of ten, and described it as "boring – really boring", and "a Z-grade, low-rent horror outing with no real scares into a genuine big-budget spectacle".[79]

Accolades, awards and nominations

[edit]At the 1st Golden Trailer Awards, it received a nomination for Most Original Trailer and won two categories: Best Horror/Thriller and Best Voice Over.[80] At the 15th Independent Spirit Awards, The Blair Witch Project won the John Cassavetes Award (for best first feature made for under $500,000).[81][82][83] The 20th Golden Raspberry Awards gave Heather Donahue its Worst Actress award, and nominated producers Robin Cowie and Gregg Hale for the Worst Picture award.[84][85] At the Stinkers Bad Movie Awards, the film won the Biggest Disappointment category and received three nominations: Worst Picture (Cowie and Hale), Worst Actress (Donahue), and Worst Screen Debut (Heather, Michael, Josh, the Stick People and the world's longest running batteries).[86]

Legacy

[edit]An array of other films have relied on the found-footage concept and shown influence by The Blair Witch Project.[87][71] These include Paranormal Activity (2007), REC (2007), Cloverfield (2008),[87] The Last Exorcism (2010), Trollhunter (2010),[88] Chronicle (2012), Project X (2012), V/H/S (2012), End of Watch (2012),[71][89] and The Den (2013).[88]

Some critics have also noted that the film's basic plot premise and narrative style are strikingly similar to Cannibal Holocaust (1980) and The Last Broadcast (1998).[69][70] Although Cannibal Holocaust director Ruggero Deodato has acknowledged the similarities of The Blair Witch Project to his film, he criticized the publicity that it received for being an original production;[90] advertisements for The Blair Witch Project also promoted the idea that the footage is genuine.[5] Despite initial reports that The Last Broadcast creators—Stefan Avalos and Lance Weiler—had alleged that The Blair Witch Project was a complete rip-off of their work and would sue Haxan Films for copyright infringement, they repudiated these allegations. One of the creators told IndieWire in 1999: "If somebody enjoys The Blair Witch Project there is a chance they will enjoy our film, and we hope they will check it out".[91]

In 2017, the Library of Congress described how The Blair Witch Project "established a new type of documentary psychological horror genre [...] One of the key elements to the film’s success was the creation of a rich fictitious history, which has become the template for modern horror film screenplay writing".[92] Film critic Michael Dodd has argued that the film is an embodiment of horror "modernizing its ability to be all-encompassing in expressing the fears of American society". He noted that "in an age where anyone can film whatever they like, horror needn't be a cinematic expression of what terrifies the cinema-goer, it can simply be the medium through which terrors captured by the average American can be showcased".[93]

In 2008, The Blair Witch Project was ranked by Entertainment Weekly as number ninety-nine on their list of 100 Best Films from 1983 to 2008.[94] In 2006, the Chicago Film Critics Association ranked it as number 12 on their list of Top 100 Scariest Movies.[95] It was ranked number 50 on Filmcritic.com's list of 50 Best Movie Endings of All Time.[96] In 2016, it was ranked by IGN as number 21 on their list of Top 25 Horror Movies of All Time,[97] number 16 on Cosmopolitan's 25 Scariest Movies of All Time,[98] and number three on The Hollywood Reporter's 10 Scariest Movies of All Time.[99] In 2013, the film also made the top-ten list of The Hollywood Reporter's highest-grossing independent films of all time, ranking number six.[100]

Director Eli Roth has cited the film as a marketing influence to promote his 2002 horror film Cabin Fever with the internet.[101] The Blair Witch Project was included in the book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[102]

After the film was released, in late November 1999, the historic house where it was filmed was reportedly being overwhelmed by film fans who broke off chunks as souvenirs. The township ordered the house demolished the next month.[24]

Media tie-ins

[edit]Books

[edit]In September 1999, D. A. Stern compiled The Blair Witch Project: A Dossier. Building on the film's "true story" angle, the dossier consisted of fictional police reports, pictures, interviews, and newspaper articles presenting the film's premise as fact, as well as further elaboration on the Elly Kedward and Rustin Parr legends. Another "dossier" was created for Blair Witch 2. Stern wrote the 2000 novel Blair Witch: The Secret Confessions of Rustin Parr. He revisited the franchise with the novel Blair Witch: Graveyard Shift, which features original characters and plot.[103]

A series of eight young adult books, titled The Blair Witch Files, were released by Random subsidiary Bantam from 2000 to 2001. The books center on Cade Merill, a fictional cousin of Heather Donahue, who investigates phenomena related to the Blair Witch. She tries to learn what really happened to Heather, Mike, and Josh.[104]

Comic books

[edit]In July 1999, Oni Press released a one-shot comic promoting the film, titled The Blair Witch Project #1. Written and illustrated by Cece Malvey, the comic was released in conjunction of the film.[105] In October 2000, coinciding with the release of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2, Image Comics released a one-shot called Blair Witch: Dark Testaments, drawn by Charlie Adlard.[103]

Video games

[edit]In 2000, Gathering of Developers released a trilogy of computer games based on the film, which greatly expanded on the myths first suggested in the film. The graphics engine and characters were all derived from the producer's earlier game Nocturne.[106]

The first volume, Rustin Parr, received the most praise, ranging from moderate to positive, with critics commending its storyline, graphics and atmosphere; some reviewers even claimed that the game was scarier than the film.[107] The following volumes, The Legend of Coffin Rock and The Elly Kedward Tale, were less well received, with PC Gamer saying that Volume 2's "only saving grace was its cheap price",[108] and calling Volume 3 "amazingly mediocre".[109]

Bloober Team developed Blair Witch, a first-person survival horror game based on the Blair Witch franchise.[110] The game was released on August 30, 2019.

Documentary

[edit]The Woods Movie (2015) is a feature-length documentary exploring the production of The Blair Witch Project.[111] For this documentary, director Russ Gomm interviewed the original film's producer, Gregg Hale, and directors Eduardo Sánchez and Daniel Myrick.[112]

Parodies

[edit]The Blair Witch Project inspired a number of parody films, including Da Hip Hop Witch, The Bogus Witch Project, The Dairy Witch, The Tony Blair Witch Project (all in 2000), and The Blair Thumb (2001),[113] as well as the pornographic films The Erotic Witch Project[113] and The Bare Wench Project.[114] The film also inspired the Halloween television special The Scooby-Doo Project, which aired during a Scooby-Doo, Where Are You! marathon on Cartoon Network on October 31, 1999. 2013's 6-5=2 was also inspired by this film.[114][115]

Sequels

[edit]A sequel titled Book of Shadows was released on October 27, 2000; it was poorly received by most critics.[116][117] A third installment announced that same year did not materialize.[118]

At San Diego Comic-Con in July 2016, a surprise trailer for Blair Witch was revealed.[119] The film was originally marketed as The Woods so as to be an exclusive surprise announcement for those in attendance at the convention. The film, distributed by Lionsgate, was slated for a September 16 release and stars James Allen McCune as the brother of the original film's Heather Donahue.[120][121] Directed by Adam Wingard, Blair Witch is a direct sequel to The Blair Witch Project, and does not acknowledge the events of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2. However, Wingard has said that although his version does not reference any of the events that transpired in Book of Shadows, the film does not necessarily discredit the existence of Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2.[122] Screenwriter Simon Barrett explained that in writing the new film, he only considered material that was produced with the involvement of the original film's creative team (directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez, producer Gregg Hale, and production designer Ben Rock) to be "canon", and that he did not take any material produced without their direct involvement—such as the first sequel Book of Shadows or The Blair Witch Files, a series of young adult novels—into consideration when writing the new sequel.[122]

In April 2022, Lionsgate was looking to reboot The Blair Witch Project with a new installment.[123] A new installment of The Blair Witch Project is officially in development at Lionsgate with Jason Blum and Roy Lee producing as of April 2024.[124]

Television

[edit]In October 2017, co-director Eduardo Sánchez revealed that he and the rest of the film's creative team were developing a Blair Witch television series, though he clarified that any decisions would ultimately be up to Lionsgate now which owns the rights to it.[125][126] The series was later announced to be released on the studio's new subsidiary, Studio L, which specializes in digital releases.[127]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Harris, Dana (March 14, 2000). "Summit rises for 'Escapade'". Variety. Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". British Board of Film Classification. August 4, 1999. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved July 28, 2016.

- ^ Stephen Galloway (January 18, 2020). "What Is the Most Profitable Movie Ever?". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c d "The Blair Witch Project". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on April 24, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Klein, Joshua (July 22, 1999). "Interview – The Blair Witch Project". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on January 21, 2015. Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ^ a b Kaufman, Anthony (July 14, 1999). "Season of the Witch". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on March 3, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2006.

- ^ a b c d "Heather Donohue – Blair Witch Project". KAOS 2000 Magazine. August 14, 1999. Archived from the original on March 30, 2010. Retrieved July 30, 2006.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Lyons, Charles (September 8, 1999). "'Blair' timeline". Daily Variety. p. A2.

- ^ a b c d "An Exclusive Interview with Dan Myrick, Director of The Blair Witch Project". House of Horrors. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ a b "Film Special: With Dan Myrick and Eduardo Sanchez". The Washington Post. June 30, 1999. Archived from the original on June 15, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ Loewenstein, Melinda (March 16, 2013). "How Joshua Leonard Fell In Love With Moviemaking". Backstage. Archived from the original on March 9, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ a b Rock, Ben (August 15, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project: Part 3 – Doom Woods Preppers". Dread Central. Archived from the original on March 28, 2017. Retrieved March 27, 2017.

- ^ Rock, Ben (August 1, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project: Part 1 – Witch Pitch". Dread Central. Archived from the original on December 30, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ Aloi, Peg (July 11, 1999). "Blair Witch Project – an Interview with the Directors". The Witches' Voice. Archived from the original on May 25, 2006. Retrieved July 29, 2006.

- ^ a b Conroy, Tom (July 14, 1999). "The Do-It-Yourself Witch Hunt". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 1, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2006.

- ^ a b c d Rock, Ben (August 22, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project Part 4: Charge of the Twig Brigade". Dread Central. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c D'Angelo, Mike (October 28, 2014). "15 years beyond the hype and hatred of The Blair Witch Project / The Dissolve". The Dissolve. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014.

- ^ Metz, Cade. PC Magazine May 23, 2006: Making an indie film. pp. 76–82.

- ^ Lim, Dennis (July 14, 1999). "Heather Donahue Casts A Spell". The Village Voice. Archived from the original on December 4, 2007. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

- ^ a b c John Young (July 9, 2009). "'The Blair Witch Project' 10 years later: Catching up with the directors of the horror sensation". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ^ Wallace, James. TFW 2014: 15 Years of The Blair Witch Project. YouTube. Event occurs at 28:58. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ Kirk, Jeremy (August 23, 2011). "32 Things We Learned From the 'Blair Witch Project' Commentary Track". Film School Rejects. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

When the three are running through the woods and Heather yells, "What the fuck is that?" at something off-camera, she is really reacting to art director Ricardo Moreno dressed in white long-johns, white stockings, and white pantyhose pulled over his head running alongside them.

- ^ Colburn, Randall (October 28, 2015). "Beyond Blair Witch: Why found-footage horror deserves your respect". The A.V. Club. Retrieved May 30, 2019.

Thus, masked men in trees and, lacking that, the persevering question of just what exactly Blair Witch's Donahue is screaming at as she runs from the tent. According to the DVD commentary, it was art director Ricardo Moreno. He was running alongside Donahue, wearing white long-johns, white stockings, and white pantyhose pulled over his head.

- ^ a b Atwood, Liz (November 25, 1999). "House used in 'Witch' due to be demolished". The Baltimore Sun. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ Rock, Ben (August 29, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project: Part 5 – The Art of Haunting". Dread Central. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (January 15, 2009). "The Blair Witch Project". Time. Archived from the original on December 26, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (September 19, 2016). "Blair Witch Flop Scares Up Horrific Memories For Joe Berlinger". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ Lodge, Guy (September 11, 2016). "Film Review: Blair Witch". Variety. Archived from the original on October 25, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ^ [4][27][28]

- ^ a b c "Q&A: 'Blair Witch Project' celebrates 20th anniversary in Frederick". WTOP News. October 16, 2019.

- ^ Rock, Ben (September 5, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project: Part 6 – Guerrilla Tactics". Dread Central. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ a b c Kinane, Ruth (April 5, 2017). "The Blair Witch Project almost ended with a different terrifying fate". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on June 3, 2017. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Rock, Ben (September 12, 2016). "The Making of The Blair Witch Project: Part 7 – The Embiggening". Dread Central. Archived from the original on September 19, 2016. Retrieved March 19, 2017.

- ^ a b Lyons, Charles (September 8, 1999). "Season of the 'Witch'". Daily Variety. p. A2.

- ^ Vary, Adam B. (June 12, 2024). "'The Blair Witch Project' Actors Call Out 'Reprehensible Behavior' After Missing Out on Profits for Decades: 'Don't Do What We Did' (EXCLUSIVE)". Variety. Retrieved June 12, 2024.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (August 17, 1999). "Blair Witch Proclaimed First Internet Movie". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on April 30, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2012.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (October 30, 2015). "Was The Blair Witch Project The Last Great Horror Film?". BBC News. Archived from the original on October 30, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2015.

- ^ "The 12 Ballsiest Movie Publicity Stunts". MTV. July 24, 2016. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Davidson, Neil (August 5, 2013). "The Blair Witch Project: The best viral marketing campaign of all time". MWP Digital Media. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Amelia River (July 11, 2014). "The Greatest Movie Viral Campaigns". Archived from the original on February 11, 2015. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Hawkes, Rebecca (July 25, 2016). "Why did the world think The Blair Witch Project really happened?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on January 9, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project Official Website: The Aftermath". blairwitch.com. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016.

- ^ DiOrio, Carl (July 19, 2009). "Steve Rothenberg dies at age 50". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on February 1, 2010. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ McNary, Dave (July 20, 2009). "Lionsgate's Steven Rothenberg dies". Variety. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved August 2, 2009.

- ^ Bowies, Scott. "'Blair Witch Project': Still a legend 15 years later". USA Today. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved February 24, 2016.

- ^ a b "Curse of the Blair witch". Entertainment Weekly. October 29, 1999. Archived from the original on September 3, 2016. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ "The Blair Witch". blairwitch.com. Archived from the original on July 7, 2007. Retrieved August 4, 2016.

- ^ christophernguyen726 (April 16, 2019). "The Blair Witch Project: Blu-ray Vs. FX Television Broadcast". Bootleg Comparisons. Retrieved April 17, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "What's Hot". Los Angeles Times. October 14, 1999.

- ^ "Billboard". November 6, 1999 – via Google Books.

- ^ Hunt, Bill (October 21, 1999). "DVD Review – The Blair Witch Project". The Digital Bits. Archived from the original on January 13, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Beierle, Aaron (January 4, 2000). "The Blair Witch Project". DVD Talk. Archived from the original on August 17, 2014. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ Sporich, Brett (October 8, 1999). "Panel Touts 55 Million DVDs Shipped in '99". videostoremag.com. Archived from the original on October 21, 2000. Retrieved October 14, 2019.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ DVD Talk

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". High Def Digest. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2016.

- ^ The Blair Witch Project Limited Edition Blu-ray. Retrieved September 28, 2024 – via www.blu-ray.com.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project: July 30 – August 1, 1999 Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on September 2, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project: August 6–8, 1999 Weekend Box Office". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 18, 2016. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ^ "1999 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 15, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ Kerswell, J.A. (2012). The Slasher Movie Book. Chicago, Ill.: Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1556520105.

- ^ Groves, Don (February 19, 2001). "'Hannibal' appeals to all tastes o'seas". Variety. p. 12.

- ^ Wax, Emily (July 30, 1999). "The Dizzy Spell of 'Blair Witch Project'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 29, 2014. Retrieved March 1, 2012.

- ^ a b Ebert, Roger. "The Blair Witch Project Movie Review (1999)". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Smolinski, Julieanne (February 7, 2012). "The Nostalgia Fact-Check: Does The Blair Witch Project Hold Up?". Vulture. Archived from the original on September 1, 2017. Retrieved January 26, 2018.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- ^ "The Blair Witch Project". Metacritic. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- ^ Nordine, Michael (September 6, 2016). "The Blair Witch Project Honest Trailer: Revisit the Horror Classic Before Seeing Adam Wingard's Secret Sequel". IndieWire. Archived from the original on November 13, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Singer, Matt (August 13, 2015). "25 Movies With Completely Baffling CinemaScores". ScreenCrush. Retrieved October 17, 2017.

The film is located at page five of the article's image gallery.

- ^ a b Rawson-Jones, Ben (October 22, 2014). "The Blair Witch Project 15 years on: The horror movie that changed everything". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on March 16, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b Schaefer, Sandy (September 17, 2016). "Blair Witch and the Evolution of the Found-Footage Genre". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ a b c Trumbore, Dave (September 16, 2016). "The Blair Witch Project Effect: How Found Footage Shaped a Generation of Filmmaking". Collider. Complex. Archived from the original on October 22, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Williams, Mary Elizabeth (June 13, 2014). "Horror's first viral hit: How The Blair Witch Project revolutionized movies". Salon. Archived from the original on January 16, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ [69][70][71][72]

- ^ Travers, Peter (July 30, 1999). "The Blair Witch Project". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ McCarthy, Todd (January 26, 1999). "Review: The Blair Witch Project". Variety. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Schwarzbaum, Lisa (July 23, 1999). "The Blair Witch Project". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Sarris, Andrew (August 16, 1999). "Who's Afraid of The Blair Witch Project?". The New York Observer. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "The Worst DUD". The Christian Science Monitor. July 23, 1999. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Schaffer, R.L. (October 26, 2010). "The Blair Witch Project Blu-Ray Review". IGN. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Trailer Awards: Nominees (1999)". Golden Trailer Awards. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved March 18, 2017.

- ^ Gordon, Naomi; Armitage, Hugh (September 12, 2016). "What happened to the Blair Witch Project cast?". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ 15th annual Spirit Awards ceremony - FULL SHOW |2000 |Film Independent on YouTube

- ^ "'Election' wins 3 Independent Spirit awards". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. March 27, 2000. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ^ Reid, Joe (January 23, 2013). "13 Great Movies Nominated for Razzie". MTV. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ Meslow, Scott (September 16, 2016). "The Blair Witch Project's Heather Donahue Is Alive and Well". GQ. Archived from the original on October 29, 2016. Retrieved February 27, 2017.

- ^ "1999 22nd Hastings Bad Cinema Society Stinkers Awards". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on January 3, 2007. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- ^ a b Barnett, David (September 15, 2016). "Blair Witch was a revelation, but found footage owes its roots to classic books". The Independent. Archived from the original on September 17, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ a b Crucchiola, Jordan (September 16, 2016). "Charting The Blair Witch Project's Influence Through 10 Horror Films That Followed". Vulture. Archived from the original on December 11, 2016. Retrieved June 17, 2017.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (March 3, 2012). "Project X and Chronicle prove that the found-footage way of making a movie can be applied to...anything. And that now it will be". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on February 11, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2017.

- ^ De Angelis, Michéle (Director) (June 22, 2003). In the Jungle: The Making of Cannibal Holocaust (Motion picture). Italy: Alan Young Pictures.

- ^ Hernandez, Eugene (August 9, 1999). "Editorial: Blair Witch v. Last Broadcast — Has It Really Come to This?". IndieWire. Archived from the original on August 5, 2017. Retrieved January 11, 2017.

- ^ "Library Highlights Horrors of "The Blair Witch Project"". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 10, 2024.

- ^ "Safe Scares: How 9/11 caused the American Horror Remake Trend (Part One)". The Missing Slate. August 31, 2014. Archived from the original on October 11, 2014.

- ^ "The New Classics: Movies EW 1000: Movies – Movies – The EW 1000 – Entertainment Weekly". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on August 7, 2009.

- ^ Soares, Andre. "Scariest Movies Ever Made: Chicago Critics' Top 100". Alt Film Guide. Archived from the original on June 4, 2015. Retrieved February 10, 2017.

- ^ Null, Christopher (January 1, 2006). "The Top 50 Movie Endings of All Time". Filmcritic.com. Archived from the original on August 20, 2006. Retrieved July 30, 2006.

- ^ "Top 25 Horror Movies of All Time". IGN. August 22, 2016. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ McClure, Kelly (October 17, 2016). "The 25 Scariest Movies of All Time". Cosmopolitan. Archived from the original on February 20, 2017. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Mintzer, Jordan (October 26, 2016). "Critic's Picks: 10 Scariest Movies of All Time". The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ "Top 10: Indies at the Box Office". The Hollywood Reporter. June 3, 2013. Archived from the original on January 30, 2017. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ^ Roth, Eli. Cabin Fever DVD, Lions Gate Entertainment, 2004, audio commentary. ASIN: B0000ZG054

- ^ Schneider, Steven Jay, ed. (2015). 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die. Quintessence Editions (9th ed.). Hauppauge, New York: Barron's Educational Series. p. 874. ISBN 978-0-7641-6790-4. OCLC 796279948.

- ^ a b Lesnick, Silas (September 16, 2016). "The Complete Blair Witch Legend". CraveOnline. Archived from the original on January 10, 2017. Retrieved January 9, 2017.

- ^ Merill, Cade (2000). "Cade Merill's The Blair Witch Files". Random House. Archived from the original on December 7, 2008. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ^ Kleinhenz, Marc N. (September 20, 2016). "A Complete Guide to the Blair Witch Mythology". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on February 26, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- ^ Smith, Jeff (April 14, 2000). "Blair Witch Project Interview". IGN. Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Blair Witch Volume I: Rustin Parr". Metacritic. Archived from the original on August 14, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ "Blair Witch 2: The Legend of Coffin Rock". PC Gamer: 88. February 2001.

- ^ Williamson, Colin (April 2001). "Blair Witch Volume 3: The Elly Kedward Tale". PC Gamer: 90. Archived from the original on March 11, 2005. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ "Bloober Team - Blair Witch". Retrieved September 2, 2019.

- ^ "Blair Witch Documentary Goes into The Woods Movie". Dread Central. January 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 14, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ "Finally a Doc On 'The Blair Witch Project' – Trailer For "The Woods Movie"". Bloody Disgusting. January 1, 2006. Archived from the original on February 13, 2015. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ a b Greene, Heather (2018). Bell, Book and Camera: A Critical History of Witches in American Film and Television. McFarland & Company. p. 177. ISBN 978-1476662527.

- ^ a b Heller-Nicholas, Alexandra (2014). Found Footage Horror Films: Fear and the Appearance of Reality. McFarland & Company. p. 113. ISBN 978-0786470778.

- ^ Morgan, Chris (June 2, 2016). "How the 1999 Scooby Doo Project Parody Inspired Adult Swim's Absurdist, Stoner Comedy". Paste. Retrieved September 4, 2020.

- ^ Hanley, Ken W. (January 19, 2015). "Book of Shadows: Blair Witch 2". Fangoria. Stream to Scream. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ Singer, Matt (October 20, 2010). "Five Lessons We Hope "Paranornal Activity 2" Learned from "Blair Witch 2"". IFC. Archived from the original on July 17, 2015. Retrieved July 15, 2015.

- ^ "Blair Witch 3". Yahoo! Movies. January 1, 2006. Archived from the original on May 9, 2006. Retrieved July 28, 2006.

- ^ Bibbiani, William (July 23, 2016). "Comic-Con 2016 Review: The (Blair) Witch is Back!". CraveOnline. Archived from the original on January 12, 2017. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- ^ Woerner, Meredith. "'Blair Witch' sequel surprises Comic-Con with a secret screening and trailer". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ Collis, Clark. "Secret Blair Witch sequel gets new trailer, September release date". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 24, 2016. Retrieved July 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Eisenberg, Eric (September 14, 2016). "Why The New Blair Witch Movie Ignores Book Of Shadows: Blair Witch 2". Cinemablend. Archived from the original on October 4, 2016.

- ^ "Lionsgate reportedly looking to relaunch Blair Witch Project with new instalment". Flickering Myth. April 20, 2022. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ Couch, Aaron (April 10, 2024). "New 'Blair Witch' Movie in the Works from Lionsgate, Blumhouse". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 11, 2024.

- ^ "Eduardo Sanchez Hints at Blair Witch TV Series". Starburst. October 30, 2017. Archived from the original on January 26, 2018. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ "74 - Podcast of Horror II: The Blair Witch Project". Diminishing Returns. October 30, 2017. Retrieved October 30, 2017.

- ^ McNary, Dave (February 22, 2018). "Lionsgate Unveils 'Studio L' Digital Slate With 'Honor List', 'Most Likely to Murder'". Variety. Archived from the original on February 22, 2018. Retrieved February 23, 2018.

External links

[edit]- 1999 films

- Blair Witch

- 1990s English-language films

- 1999 directorial debut films

- 1999 hoaxes

- 1999 horror films

- 1990s supernatural horror films

- Films set in 1994

- American independent films

- American mockumentary films

- American psychological horror films

- American supernatural horror films

- American teen horror films

- Artisan Entertainment films

- Camcorder films

- Films about film directors and producers

- Films about witchcraft

- Films directed by Daniel Myrick

- Films directed by Eduardo Sánchez (director)

- Films produced by Gregg Hale (producer)

- Films set in forests

- Films set in Maryland

- Films shot in Maryland

- Films with screenplays by Daniel Myrick

- Films with screenplays by Eduardo Sánchez (director)

- Folk horror films

- Found footage films

- Golden Raspberry Award–winning films

- Haxan Films films

- Paranormal hoaxes

- Burkittsville, Maryland

- 1990s American films

- 1999 independent films

- Films set in the 1990s

- John Cassavetes Award winners

- English-language horror films

- English-language independent films