Sleep Dealer

| Sleep Dealer | |

|---|---|

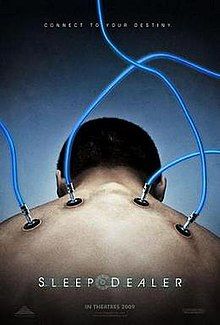

Promotional film poster | |

| Directed by | Alex Rivera |

| Written by | Alex Rivera David Riker |

| Produced by | Anthony Bregman |

| Starring | Luis Fernando Peña Leonor Varela Jacob Vargas |

| Cinematography | Lisa Rinzler |

| Edited by | Alex Rivera Jeffrey M. Werner |

| Music by | Tomandandy |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Maya Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Countries | United States Mexico |

| Languages | Spanish English |

| Box office | $107,559[1] |

Sleep Dealer is a 2008 futuristic science fiction film directed by Alex Rivera.

Sleep Dealer depicts a dystopian future to explore ways in which technology both oppresses and connects migrants.[2] A fortified wall has ended unauthorized Mexico-US immigration, but migrant workers are replaced by robots, remotely controlled by the same class of would-be emigrants. Their life force is inevitably used up, and they are discarded without medical compensation.

Plot

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (April 2018) |

Sleep Dealer is set in a future, militarized world marked by closed borders, virtual labor, and a global digital network that joins minds and experiences, where three strangers risk their lives to connect with each other and break the technology barriers.

Memo Cruz works at a factory, one of several sleep dealers. Here, workers are connected to the network via suspended cables that plug into nodes in their arms and back, allowing them to control the robots that have replaced them as unskilled labor on the other side of the border. The sleep dealers are called so because one may collapse if one works long enough. The story is told as a flashback, as Memo remembers his home in Santa Ana Del Rio, Oaxaca. His father wants him to participate in growing crops on the meager family homestead. Memo's passion, however, is electronics and hacking. The homestead also has dried up because of a dam built nearby and owned by the private corporation Del Rio Water. Memo and his father must trek on foot to buy water by the bag while monitored by security cameras armed with machine guns. The media on American hi-def TV shows glimpses of a technological dystopia, although in a positive light with superficial spin-doctoring. Memo is building an electronic receiver that can tap into communications as a hobby. As he continues to work on it, its range increases to faraway cities.

One summer, a remote-controlled military aerial vehicle operated by the security forces of Del Rio Water catches Memo monitoring a frequency used by the drones. This act warrants a brutal attack. He disconnects in time before the drone can locate him with certainty. On another occasion, he and his brother watch a live TV broadcast about a drone action that is about to destroy a building known to be intercepting drone communication. They quickly realize that the building is their own home, where Memo has his equipment, and run to save their father, whose life is in danger. However, they are too late, and the vehicle launches a rocket at the father, wounding him. The drone pilot then faces their father, seeing him through the drone’s camera, before killing him. The drone pilot is a Mexican-American named Rudy Ramirez. Memo boards a bus to the city of Tijuana to find work.

Luz Martínez also boards the same bus. Memo notices that Luz has nodes on the wrist for interfacing with the digital network and asks her where he can get them for free. She tells him that he can find someone, known as a coyotek, to connect him by asking around in a certain alley. Luz has loans and may default. She makes a living by uploading memories to an online memory trading company, TruNode, where viewers pay for content. She uploads her memory of meeting Memo.

Memo is robbed of his money during his first attempt to seek a coyotek. He finds an abandoned shack in which to stay at the edge of the city, where other node workers live. Luz gets a sale for her memory of Memo and a prepaid offer for her next memory of him. Luz finds him and learns he is out of money. She helps him get a node job at a bar that has the equipment. She is the coyotek, having learned from her ex-boyfriend, and she does him a favor.

Luz tries to upload more experiences. TruNode makes her reveal feelings rather than just the story. The person who requested the information is revealed to be Ramirez working for Del Rio Water. Luz and Memo open up to each other and have connected sex. Upon receiving the next upload, Ramirez has his doubts confirmed that his work made him kill a good man.

Memo discovers that Luz has been paid to upload her memories of him, and so he leaves her feeling betrayed. He works overtime at the sleep dealer, risking exhaustion. Luz writes to him and mails him a recording of her memories as a parting gift. In the meantime, Ramirez has crossed the fortified US-Mexican border to meet Memo. As Ramirez explains himself, Memo tries to run, perceiving danger. Ramirez catches up and explains he was under orders and offers to help.

Memo rejoins Luz and recruits her help to connect Ramirez to the network. He accesses the Del Rio Water security network to control one of the company's drones. Upon discovery that Ramirez is not heeding orders, other drones pursue Ramirez. After heated aerial dogfighting, Ramirez manages to blast a hole in the dam, directly where Memo's father had once tossed a pebble in helpless frustration. Memo receives news from his home and neighboring subsistence farms, celebrations of returning ancestral waters, albeit not necessarily a permanent one. Ramirez goes farther south in Mexico as he can no longer return to his family in the US. Memo moves on with his life in Tijuana.

Cast

[edit]- Leonor Varela as Luz Martínez

- Jacob Vargas as Rudy Ramirez

- Luis Fernando Peña as Memo Cruz

Reception

[edit]Sleep Dealer was generally well received by critics, with a 70% on Rotten Tomatoes.

The movie won the Waldo Salt Screenwriting Award,[3] the Alfred P. Sloan Prize[4] at the 2008 Sundance Film Festival, The H.R. Giger Award for the Best International Film at The Neuchâtel International Fantastic Film Festival, and a special mention Amnesty International Film Prize at the 2008 Berlin Film Festival. The film was nominated for the Breakthrough Director Award at the Gotham Independent Film Awards 2008, and an Independent Spirit Award for Best First Feature in 2009.

A.O. Scott, of The New York Times wrote "Exuberantly entertaining — a dystopian fable of globalization disguised as a science-fiction adventure…. Mr. Rivera — a brilliant young director — takes his audience into a future of “aqua-terrorism” and cyberlabor that I wish I could dismiss as implausible..." in his review of the 2008 New Directors/New Films Festival.[5]

Kenneth Turan, of the Los Angeles Times wrote "Adventurous, ambitious and ingeniously futuristic, "Sleep Dealer" is a welcome surprise. It combines visually arresting science fiction done on a budget with a strong sense of social commentary in a way that few films attempt, let alone achieve..." in his review of the film.[6]

Cultural impact

[edit]Sleep Dealer’s cultural impact relates to its social commentary on contemporary issues through the lens of science-fiction. Javier Ramírez remarks that Rivera’s “innovative deployment of science fiction encourages us to question our present reality, by projecting into the future.”[7] Through his imagining of a possible future, Rivera critiques today’s issues including immigration, drone warfare, and technological advances. His film is part of the emerging genre of speculative fiction called Latinxfuturism or Chicanafuturism, of which both have roots in Afrofuturism. Chicanafuturism de-familiarizes the familiar and challenges the status quo of society by re-imagining reality or providing alternative representations. In his film review in the New York Times, A.O. Scott writes that “Mr. Rivera’s vision of Tijuana…is…an unsettlingly plausible extrapolation of what that city already represents.”[8] In this way, Rivera uses the reality of what Tijuana and the maquiladoras represent for Mexicans and society as a whole to project a dystopian possibility of what its progress may become, making the audience question current conditions. The possibility of complete human exploitation of foreign labor markets through the use of nodes becomes a little less fictional with the referential point of Tijuana today, thus, de-familiarizing what is familiar.

Arguably the most important cultural impact of the film, Sleep Dealer provides representation of people of color and humanizes political issues through characters such as Memo and Luz. David Montgomery of The Washington Post comments that the film “puts a human face on all” the problems explored in the movie.[9] The significance of seeing oneself in the stories told about the future is not lost on the film makers or its reviewers. Part of the goal of Chicanafuturist works is situating people of color as the protagonists in the representations of what our world could be. Montgomery goes on to comment, “The whole world has a future, yet ‘Sleep Dealer’ is one of the first science fiction films largely set in the underdeveloped parts — a milestone in film history.”[9]

The placing of people of color within a pre-existing system is part of the rebellion against hegemonic colonial narratives with which Chicanafuturism contends. The other Chicanafuturism path is creating alternative systems that people of color exist in without the restraints of the present reality. In Aimee Bahng’s book Migrant Futures, she points out that “Sleep Dealer argues for and instantiates the production of alternative futures that fight against not only obsolescence but also obfuscations of the past that paved the way for the colonization of the future.”[10] That is to say, Sleep Dealer not only criticizes the current system but works to deconstruct the narrative mechanisms that uphold colonial influences. Sleep Dealer contributes to the Latinxfuturist works that try to represent people of color as well as re-imagine a future without the colonialist androcentric oppressive forces that mark today’s society.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Sleep Dealer, Box Office Mojo

- ^ Crossed Genres. "Interview - Alex Rivera". Crossed Genres. Retrieved 29 October 2012.

- ^ "2008 Sundance Film Festival Announces Awards" (PDF). 2008-01-26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-18.

- ^ "Sleep Dealer Wins Alfred P. Sloan Prize at 2008 Sundance Film Festival" (PDF). 2008-01-25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-06-25.

- ^ Scott, A.O. (March 26, 2008). "Big Ideas in Deceptively Small Packages". The New York Times.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (April 17, 2009). "A nightmare that looks all too real". The Los Angeles Times.

- ^ Ramirez, Javier (2016). "Sci-Fi-ing Immigration and the U.S.-Mexico Border: An Interview with Filmmaker Alex Rivera". Chiricú. 1 (1): 95–105. doi:10.2979/chiricu.1.1.07. ISSN 0277-7223. JSTOR 10.2979/chiricu.1.1.07. S2CID 151938192.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (2009-04-16). "Tale of an Anxious Wanderer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ a b Montgomery, Davis (2014-07-14). "Alex Rivera's lost cult hit "Sleep Dealer" about immigration and drones is back". Washington Post. Retrieved 2020-05-05.

- ^ Bahng, Aimee (16 April 2018). Migrant futures : decolonizing speculation in financial times. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-7301-8. OCLC 982533289.

External links

[edit]- 2008 films

- 2008 multilingual films

- 2008 science fiction films

- Alfred P. Sloan Prize winners

- American science fiction films

- Cyberpunk films

- 2000s English-language films

- American multilingual films

- Mexican multilingual films

- Films about telepresence

- American independent films

- Mexican science fiction films

- 2000s Spanish-language films

- Films set in Tijuana

- Films set in San Diego

- Films set in Colombia

- Films scored by Tomandandy

- Films about drones

- Films about privatization

- Mexican independent films

- 2008 independent films

- 2000s American films

- 2000s Mexican films

- English-language science fiction films

- English-language independent films

- Spanish-language American films