The 3 Rooms of Melancholia

This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2013) |

| The 3 Rooms of Melancholia | |

|---|---|

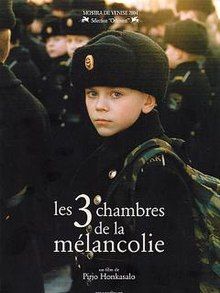

Promotional poster at the 2004 Venice Film Festival | |

| Directed by | Pirjo Honkasalo |

| Written by | Pirjo Honkasalo |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | Pirkko Saisio |

| Narrated by | Pirkko Saisio |

| Cinematography | Pirjo Honkasalo |

| Edited by |

|

| Music by | Sanna Salmenkallio |

Release date |

|

Running time | 106 minutes |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | € 560,400 |

| Box office | $19,317 (domestic) |

The 3 Rooms of Melancholia (Finnish: Melancholian 3 huonetta) is a 2004 Finnish documentary film written, directed and co-produced by Pirjo Honkasalo. The film documents the devastation and ruin brought on by the Second Chechen War, more specifically the toll that the war had taken on the children of Chechnya and Russia.

The film received positive reviews from critics and won numerous awards.

Content summary

[edit]The content of The 3 Rooms of Melancholia is divided into three chapters, each chronicling different hardships of the affected children. The film is narrated by Pirkko Saisio but narration and dialogue are sparse and the imagery is left to convey the largest part of the film's message.

Chapter one: Longing

[edit]Kronstadt is a Russian town on Kotlin Island near Saint Petersburg. A site of the infamous Kronstadt rebellion, this is where the Armed forces of the Russian Federation run and maintain the Kronstadt Cadet Academy, a boys' military academy. The film documents a part of the months-long intense training program of several hundred children between the ages of nine and fourteen, most of whom are either orphaned or from very poor families. The viewers learn that many of these children are orphans because of the war in Chechnya and that some of the children will be sent to fight this very same war once their training is complete. Some of the children and their backgrounds are presented in-depth and a bleak picture emerges about their past and their possible future lives. The viewer is also led to believe that the future Russian Army will be largely composed of children such as these. The training is intense and devoid of any enjoyment for the children; the war exercises are strenuous and endless; the children don't get to play much but, even when they do, their games are also organized into war exercises; most of the television programming that the children watch is limited to news reports about wars and terrorist attacks. Bleak and somber imagery dominates throughout the first chapter, instilling images of poverty, despair and desolation affecting the children as well as their families.

Chapter two: Breathing

[edit]The second chapter is shot in black-and-white and depicts the devastation in the city of Grozny, the Chechen capital, brought on by years of endless fighting. Numerous buildings are destroyed by bombs and the city appears devoid of normal human life. As stray dogs rummage through the rubble, the only human activities within the city seem to be military movements, homeless people and beggars dying on the streets, and humanitarian workers trying to save the children. A woman is shown dying from having drunk water contaminated with oil. Hadizhat Gataeva, a Chechen woman and humanitarian worker who collects the abandoned children and those children of dead and dying parents, is shown caringly taking the woman's three young children from her in order to take them to an orphanage where they may receive the care they need after their mother dies. The children are loaded on a bus and taken on a long trip across a desolate landscape that bears constant reminders that they're still in a war zone—such as multiple military checkpoints—until they reach an Islamic orphanage located in the autonomous region of Ingushetia.

Chapter three: Remembering

[edit]The viewers are taken to the orphanage where some of the children are profiled. An 11-year-old boy was gang-raped by Russian soldiers and was brought to the orphanage after being found in a cardboard box. Another boy was brought in after he survived a fall from a ninth-floor apartment; his mother threw him off the balcony after her husband's death in the First Chechen War. A girl, now 19, was 12 years old when she was raped by Russian soldiers. The last few minutes of the film show a mysterious but ancient religious ceremony performed on a Muslim farm; a goat is killed—for food as well as for the ceremony—and the children have its blood smeared on their faces. All of this happens while more reminders of the war present themselves as fighter aircraft fly overhead.

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The film received a generally positive response from film critics being awarded favorable reviews as well as winning eleven major film awards while being nominated for four more. As of February 27, 2009, the film scored a 70% positive rating on aggregate review website Rotten Tomatoes[1] and a rating of 67/100 on Metacritic.[2]

In the September 2005 issue of the British Film Institute's Sight & Sound magazine, critic Leslie Felperin proclaimed The 3 Rooms of Melancholia to be "one of the finest documentaries of the past year".[3] Stephen Holden of The New York Times called the film a "magnificent documentary" as well as proclaiming that it is "one of the saddest films ever made".[4] About the film's imagery and intended message, Holden said that the "film mostly lets its images speak for themselves".[4] Andrew O'Hehir of Salon.com paid tribute to Honkasalo's work by calling her "an artist with a piercing eye, tremendous patience and a rigorous formal technique" and proclaiming the film "a prodigious, almost spiritual experience".[5] Joshua Land of The Village Voice opines that the film was "beautifully shot" and that it is "made with undeniable intelligence" while, at the same time, calling Honkasalo's approach "high-art".[6] Critic Noel Murray of The A.V. Club, a publication of The Onion, shared some of Joshua Land's sentiments with regards to the film's artistic achievement. He called The 3 Rooms Of Melancholia "a challenging and beautiful film", called Honkasalo's approach "more impressionistic than informative" and concluded that "as art, 3 Rooms is magnificent."[7]

Accolades

[edit]Won

[edit]- International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam (2004)

- Amnesty International - DOEN Award - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Full Frame Documentary Film Festival (2005)

- Seeds of War - Pirjo Honkasalo (Tied with Eugene Jarecki and Susannah Shipman for Why We Fight)

- Jussi Awards (2005)

- Best Documentary Film - Auli Mantila

- Best Music - Sanna Salmenkallio

- Prix Italia (2005)

- TV Documentaries - Current Affairs

- Tampere Film Festival (2005)

- Main Prize, Finnish Short Film Over 30 minutes - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Thessaloniki Documentary Festival (2005)

- FIPRESCI Prize - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Venice Film Festival (2004)

- EIUC Award - Special Mention - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Human Rights Film Network Award - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Lina Mangiacapre Award - Pirjo Honkasalo

- Yerevan International Film Festival (2005)

- Grand Prix - Golden Apricot, Best Documentary Film - Pirjo Honkasalo

Nominated

[edit]- Jussi Awards (2005)

- Best Cinematography - Pirjo Honkasalo (lost to Kari Sohlberg for Dog Nail Clipper)

- Mar del Plata Film Festival (2005)

- Best Film (lost to Le Grand Voyage)

- Sundance Film Festival (2005)

- Grand Jury Prize (lost to Forty Shades of Blue)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The 3 Rooms of Melancholia, Rotten Tomatoes. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ The 3 Rooms of Melancholia, Metacritic. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ Felperin, Leslie. Edinburgh 2005: The 3 Rooms Of Melacholia Archived 2009-02-01 at the Wayback Machine, Sight & Sound, September 2005. Accessed March 4, 2009.

- ^ a b Holden, Stephen. The 3 Rooms of Melancholia (2004), The New York Times, July 27, 2005. Accessed February 27, 2009.

- ^ O'Hehir, Andrew. Beyond the Multiplex - "The 3 Rooms of Melancholia" Archived 2008-01-30 at the Wayback Machine, Salon.com, July 21, 2005. Accessed March 3, 2009.

- ^ Land, Joshua. The Art of War, The Village Voice, July 19, 2005. Accessed March 3, 2009.

- ^ Murray, Noel. The 3 Rooms Of Melancholia, The A.V. Club, July 27, 2005. Accessed March 3, 2009.

External links

[edit]