Old Exe Bridge

Old Exe Bridge | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates | 50°43′08″N 3°32′10″W / 50.7190°N 3.5361°W |

| Crosses | River Exe (originally) |

| Locale | Exeter, Devon, England |

| Maintained by | Exeter City Council |

| Heritage status | Grade II listed building; scheduled monument |

| Characteristics | |

| Material | Stone |

| Total length | 590 ft (180 m) – 750 ft (230 m) |

| Width | 16 ft (4.9 m) |

| Height | 20 ft (6.1 m) |

| No. of spans | 17 or 18 |

| History | |

| Construction start | c. 1190 |

| Opened | pre-1214 |

| Closed | 1778 |

| Location | |

| |

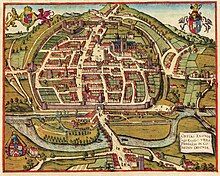

The Old Exe Bridge is a ruined medieval arch bridge in Exeter in south-western England. Construction of the bridge began in 1190, and was completed by 1214. The bridge is the oldest surviving bridge of its size in England and the oldest bridge in Britain with a chapel still on it. It replaced several rudimentary crossings which had been in use sporadically since Roman times. The project was the idea of Nicholas and Walter Gervase, father and son and influential local merchants, who travelled the country to raise funds. No known records survive of the bridge's builders. The result was a bridge at least 590 feet (180 metres) long, which probably had 17 or 18 arches, carrying the road diagonally from the west gate of the city wall across the River Exe and its wide, marshy flood plain.

St Edmund's Church, the bridge chapel, was built into the bridge at the time of its construction, and St Thomas's Church was built on the riverbank at about the same time. The Exe Bridge is unusual among British medieval bridges for having had secular buildings on it as well as the chapel. Timber-framed shops, with houses above, were in place from at least the early 14th century, and later in the bridge's life, all but the most central section carried buildings. As the river silted up, land was reclaimed, allowing a wall to be built from the side of St Edmund's which protected a row of houses and shops which became known as Frog Street. Walter Gervase also commissioned a chantry chapel, built opposite the church, which came into use after 1257 and continued until the Reformation in the mid-16th century.

The medieval bridge collapsed and had to be partially rebuilt several times throughout its life; the first recorded rebuilding was in 1286. By 1447 the bridge was severely dilapidated, and the mayor of Exeter appealed for funds to repair it. By the 16th century, it was again in need of repairs. Nonetheless, the bridge was in use for almost 600 years, until a replacement was built in 1778 and the arches across the river were demolished. That bridge was itself replaced in 1905, and again in 1969 by a pair of bridges. During construction of the twin bridges, eight and a half arches of the medieval bridge were uncovered and restored, some of which had been buried for nearly 200 years, and the surrounds were landscaped into a public park. Several more arches are buried under modern buildings. The bridge's remains are a scheduled monument and grade II listed building.

Background

[edit]Exeter was founded as Isca Dumnoniorum by the Romans in the first century CE. It became an important administrative centre for the south west of England, but travel further west (to the remainder of Devon and the whole of Cornwall) required crossing the River Exe. At Exeter, the Exe was naturally broad and shallow, making this the lowest reliable crossing point before the river's tidal estuary. There are records of a crossing from Roman times, most likely in the form of a timber bridge. No trace of any Roman bridge survives; it is likely that, once replaced, the bridge deck was simply left to degrade and any masonry supports would have been washed away by floodwaters.[1][2][3]

Bridge building was sparse in England through the Early Middle Ages (the period following the decline of the Roman Empire until after the Norman conquest of England in the late 11th century).[4][5] Work on the Pont d'Avignon in the south of France began in the 1170s. London Bridge, over the River Thames on the opposite side of England, was begun around the same time, and was completed in 1209. Several similar bridges were constructed across England in this era, of which Exeter's, London's, and the Dee Bridge in Chester were among the largest examples.[5][6] Only one other bridge of a similar age survives in Devon, at Clyst St Mary, just east of Exeter; another exists at Yeolmbridge, historically in Devon but now in Cornwall.[7]

Until the 12th century, the Exe was crossed by a ford, which was notoriously treacherous and was supplemented by a ferry for foot passengers. According to John Hooker, chamberlain of Exeter, who wrote a history of the city in the 16th century (around 400 years after the bridge was built), a rudimentary timber bridge existed at the site but this was also treacherous, particularly in the winter when the river was in flood. Hooker describes how pedestrians were washed off the bridge on several occasions and swept to their deaths.[8][9][10]

History

[edit]Construction

[edit]

A stone bridge was promoted by Nicholas and Walter Gervase, father and son and prominent local residents. The Gervases were well-off merchants. Walter was subsequently elected mayor of Exeter several times and had his parents buried in the chapel on the Exe Bridge upon their deaths (the exact dates of which are unknown); he died in 1252. The exact dates of the bridge's construction are not known, but construction began around 1190. Stone bridges often took two decades or more to complete in the Middle Ages, and the Exe Bridge was not complete until around 1210.[1][8][11] Walter travelled the country soliciting donations.[12] According to Hooker, the Gervases raised £10,000 through public donations for the construction of a stone bridge and the purchase of land which would provide an income for the bridge's upkeep.[11] No records survive of the people responsible for the design and construction of the bridge. There is a record of a bridge chaplain in 1196, which W. G. Hoskins, professor of English local history, believed to mean that the bridge was at least partially built by then. It was certainly complete by 1214, when a record exists of St Edmund's Church, which was built on the bridge.[8][13]

The bridge was at least 590 feet (180 metres) long[14] (some studies have suggested it was longer, up to 750 feet (230 metres)[15][16]) and consisted of possibly 17 or 18 arches; some accounts suggest there could have been as few as 12 arches, though the number appears to have varied over time with repairs. It crossed the Exe diagonally, starting from close to the West Gate of the city walls, and continued across the marshy banks which were prone to flooding.[1][15][16][17][18] The foundations were created using piles of timber, reinforced with iron and lead and driven in tightly enough to form a solid base. In the shallower water closer to the banks, rubble and gravel were simply tipped onto the river bed. After part of the bridge was demolished in the 18th century, some of the piles were removed and found to be jet black and extremely solid, having been underwater for some 500 years.[15][13]

Medieval history

[edit]

The size of the bridge's piers and the reclamation of land on the Exeter side reduced the width of the river by more than half, which increased the force of the water acting on the bridge, causing damage. The bridge is known to have been repaired several times throughout its life. The earliest repairs are impossible to date, but a partial collapse was recorded during a storm in 1286, and again in 1384, when several people were killed. It was rebuilt on both occasions. Later repairs can be dated by the stone used—they were made with Heavitree breccia, a local stone not quarried until the mid 14th century (approximately 150 years after the bridge was built). By 1447, the bridge was recorded as being severely dilapidated—Richard Izacke, the chamberlain of Exeter in the mid 17th century, wrote that it "was now in great decay, the stone work thereof being much foundred, and the higher part being all of timber was consumed and worn away".[19][20]

Shortly after this report, the mayor, John Shillingford, appealed for funds to rebuild it. He approached John Kemp, the Archbishop of York, with whom he was acquainted and who was an executor of the estate of the recently deceased Henry Beaufort, the famously wealthy Bishop of Winchester. Kemp promised a contribution but the process was frustrated by Shillingford's sudden death in 1458. In 1539, one of the central arches collapsed and was repaired using stone from St Nicholas' Priory but there was still no refurbishment of the whole structure.[19][21][22]

Later history

[edit]

Repairs and maintenance of the bridge were provided for from the proceeds of land bought by the Gervases at the time the bridge was built, and the funds were administered by bridge wardens. The wardens were responsible for the upkeep of the bridge until 1769, when the responsibility was passed to the Exeter turnpike trust by Act of Parliament. The trust was dissolved in 1884 and responsibility for the bridge and its estate passed to Exeter City Council.[23] The bridge wardens kept detailed records on rolls of parchment, of which most rolls from 1343 to 1711 survive, forming the most complete set of records for a bridge in Britain except those for London Bridge. The bridge estate grew to a considerable size. The records show that it leased 15 shops on the bridge, and over 50 other properties elsewhere in Exeter, including mills and agricultural land, all providing an income for maintenance and repairs. The wardens and their successors in the turnpike trust also collected tolls from carts using the bridge from outside the city (citizens of Exeter were exempt from the tolls).[24][25]

By the late 18th century, congestion around the bridge became a cause for concern. An Act of Parliament in 1773 empowered the trustees to repair or rebuild the bridge but events overtook the planned repairs when, in December 1775, a fire broke out in the Fortune of War, a pub built on the bridge. The fire consumed the pub and a neighbouring house. The pub provided cheap accommodation to local vagrants and it was believed that upwards of 30 people may have been inside at the time of the fire; at least nine bodies were recovered after the fire was extinguished.[19]

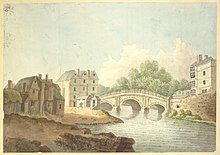

Plans for widening the medieval bridge were considered but dismissed. The spans across the river were demolished following the completion of a new, three-arch masonry bridge by Joseph Dixon in 1778. Construction of the replacement bridge began in 1770 and suffered a major setback in 1775 when floodwaters washed away much of the part-built structure and damaged its foundations.[26] This bridge was built on a different alignment, just upstream from the medieval bridge and crossing on a shorter, horizontal line. By then, the marshland over which several of the medieval arches were built had been reclaimed and the river was restricted to a width of 150 feet (46 metres). The medieval arches on the Exeter bank were left intact and eventually buried or incorporated into buildings. The 19th-century bridge was itself demolished and replaced with a three-hinged steel arch bridge in 1905, built by Sir John Wolfe Barry, who was also responsible for London's Tower Bridge. Barry's bridge lasted about 65 years before it was demolished in favour of a pair of reinforced concrete bridges, which opened in 1969 and 1972.[9][23][27]

Parts of the medieval bridge were exposed when a German bomb exploded nearby during the Exeter Blitz in the Second World War. More arches were revealed during the construction of the modern bridges.[16][28] The 20th-century engineers were careful to site the new bridges and their approach roads away from the line of the medieval bridge. At this time, part of Frog Street (a road on the river bank) was abandoned. During the work, an old brewery and several adjoining buildings along the street were demolished to make way for a new road scheme connecting with the twin bridges. One timber-framed house became known as "the House That Moved" after it was saved from demolition and wheeled to a new position.[29] The demolition uncovered five of the medieval arches and, after further excavation, another three and a half arches were exposed, estimated to be around half the original length of the bridge. Exeter City Council commissioned local stonemasons to restore the stonework, then landscaped the area around the arches into a public park to display the uncovered arches, which were in remarkably good condition, having been buried for around 200 years.[16][30][31] The bases of several of the demolished arches survive on the riverbed, and about 25 metres (82 feet) of bridge is buried under Edmund Street and the modern bank of the Exe. What remains is the oldest surviving bridge of its size in England and the oldest with a chapel still on the bridge in Britain. As such, the bridge is a scheduled monument and a grade II listed building, providing it legal protection from modification or demolition.[1][32][33][34]

- The bridge in its modern setting, bypassed by traffic and set in a landscaped park

Architecture

[edit]

About half of the bridge's original length survives unburied—eight and a half arches over about 285 feet (87 metres). Another three and a half arches, spanning 82 feet (25 metres) remain buried. The visible arches vary in span from 3.7 metres (12 feet) to 5.7 metres (19 feet). Two of them form the crypt of the bridge chapel, St Edmund's Church. It spanned the river diagonally in a north-westerly direction from what is now Exeter city centre to St Thomas (now a suburb of Exeter but originally outside the city), terminating outside St Thomas's Church, which was built at around the same time. The bridge was 16 feet (5 metres) wide on average. The roadway on the bridge was about 12 feet (4 metres) wide between the parapets at its peak, wide enough for two carts to pass side by side—unusually wide for a medieval bridge. The parapets are lost but some of the medieval paving survives, along with other, later, paving.[1][15][14]

The surviving arches are up to 20 feet (6 metres) high. The piers are rounded in the downstream direction but feature cutwaters (streamlined brickwork intended to reduce the impact of the water on the piers) facing upstream. Above the cutwaters were originally triangular recesses forming refuges for pedestrians to allow carts to pass. Local trap stone was used for the faces of the arches, behind which is gravel and rubble contained within a box of wooden stakes which were driven into the ground and the riverbed. Other stones found include sandstone and limestone from East Devon, and Heavitree breccia for later repairs. Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) has established that the oldest of these stakes came from trees felled between 1190 and 1210.[1][16][14][35]

The arches are a mix of Norman-style semi-circles and the pointed Gothic style. All are supported by ribbed vaults. The pointed arches became fashionable at about the same time as work started on the bridge and there was some suggestion that the variation was the result of repairs, but archaeological studies in the 20th century proved that the bridge was built with both types of arch.[14][36] The pointed arches have five ribs, each about 1 foot 6 inches (46 centimetres) wide and spaced between 3 feet (91 centimetres) and 3 feet 6 inches (107 centimetres) apart; the rounded arches have three ribs, ranging from 3 feet (91 centimetres) to 3 feet 6 inches (107 centimetres) wide and 2 feet 6 inches (76 centimetres) to 3 feet (91 centimetres) apart.[1][36]

Churches

[edit]

Bridge chapels were common in the Middle Ages, when religion was a significant part of daily life. The chapel provided travellers a place to pray or to give thanks for a safe journey, and the alms collected were often used towards the maintenance of the bridge.[37] A church was built on the Exe Bridge, across two of the bridge arches, and dedicated to St Edmund the Martyr. The church was built with the bridge, and its structure is an integral part of it; it had an entrance on the bridge and possibly a second entrance underneath. The first record of a bridge chaplain is from 1196, suggesting that the church may have already been built by that date. A record of the completed church exists from 1214, when it was mentioned in a list of churches in Exeter, along with St Thomas's Church. It had a rectangular plan, 54 feet (16 metres) long by 16 feet 6 inches (5 metres) wide. Its south wall rested on the north side (right-hand side when crossing from the Exeter side) of the bridge and its side walls rested on the cutwaters while the north wall was supported by piers rising from the riverbed which had their own cutwaters. The bridge arch below the aisle was blocked in the 17th century, showing that by that time the river did not flow under the church.[15][38] A seal of the bridge was made for use by the bridge wardens, probably shortly after its opening, showing the outline of St Edmund's Church (or possibly the chantry chapel) with houses on either side. The oldest known document with the seal on was addressed to the mayor of Exeter in either 1256 or 1264.[39]

The church was extended several times during the bridge's lifetime. By the end of the 14th century, accumulated silt on the Exeter side allowed a portion of land to be reclaimed, leaving the west wall of the church above dry land. Thus, the north wall was partially demolished to allow an aisle to be added, adding 7 feet (2 metres) to the width of the church. Work on a bell tower began in 1449 after Edmund Lacey, the Bishop of Exeter, offered indulgences in exchange for financial contributions. Indulgences, in which senior clergymen offered reduced time in purgatory in exchange for acts of charity, were a common method of funding bridges in the Middle Ages.[40][41][42] Further extensions followed in the 16th century, by which time the area of land reclaimed from the river had grown, and several of the bridge arches were on dry land. It is likely that there was little or no water flowing under the arches supporting the church by this point, except during winter floods. The church was struck by lightning in 1800 and largely rebuilt in 1834, then severely damaged in a fire in 1882 and repaired the following year, though retaining much of the ancient stonework. Another fire in 1969 left the church in a ruinous state, and it was partially demolished in 1975, when most of the later additions were removed but the medieval stonework was preserved. Although ruined, the tower survives at its original height—the only intact part of the church.[1][9][38][43]

On the opposite side of the bridge was a smaller chantry chapel (a chapel employing a priest to pray for a given period of time after a person's death, to aid that person's passage to heaven), built for Walter Gervase and dedicated to the Blessed Virgin Mary. Upon his death in 1257, Gervase left an endowment of 50 shillings a year for a priest to hold three services a week to pray for him, his father, and his family. The chapel continued in use until at least 1537 but was destroyed in 1546 during the dissolution of the monasteries. Only stone fragments from the foundations survive. According to Hooker, Gervase and his wife were buried in another chapel, attached to St Edmund's Church, in which there was a "handsome monument" to Gervase's memory. This chapel was alienated from the church during the Reformation and converted into a private house; the monument was removed and defaced. Only the foundations of the chapel remained by the 19th century.[1][38][44][45]

At the western end of the bridge (on dry land) was St Thomas's Church, built at a similar time to the bridge. The exact date of construction is unknown, but it was dedicated to St Thomas Becket, who was canonised in 1173, and the first known record of it dates from 1191. It became the parish church for Cowick (most of the area is now known as St Thomas) in 1261. The church was swept away in a major flood at the beginning of the 15th century and rebuilt further away from the river. The new building, on Cowick Street, was consecrated in 1412. It underwent significant rebuilding in the 17th and 19th centuries after it was set alight during the English Civil War. The church is a grade I listed building.[38][46][47]

Secular buildings

[edit]Bridge chapels were common on medieval bridges but secular buildings were not. Around 135 major stone bridges were built in Britain in the medieval era. Most, though not all, had some form of bridge chapel either on the bridge itself or on the approach, but only 12 are documented as having secular buildings on the bridge, of which the only surviving example with buildings intact is High Bridge in Lincoln. The Exe Bridge had timber-framed houses on it from early in its life—the earliest record is of two shops, with houses above, from 1319. At the height of development, all but the six arches in the middle of the river supported buildings. They were built with their front walls resting on the parapets of the bridge and the rest of the building supported by wooden posts in the riverbed, until they were demolished in 1881.[1][15][48][49]

In the later 13th century, silty deposits had built up on the Exeter side of the bridge, allowing the land to be reclaimed for two buildings which backed onto the river and fronted onto what became Frog Street. Archaeological evidence suggests that one of the two was possibly a tannery. The houses were demolished in the post-medieval era but the foundations survived. Several buildings were constructed next to the bridge on the Exeter side, protected from the river by a wall which extended from the west side of the church.[1][50]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Bibliography

[edit]- Brierley, J. (February 1979). "The Mediaeval Exe Bridge". Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers. 66 (1): 127–139. doi:10.1680/iicep.1979.2269. ISSN 1753-7789.

- Brown, Stewart (2010). The Exe Bridge, Exeter (PDF). Exeter: Exeter City Council. ISBN 978-1-84785-004-1.

- Cook, Martin (1998). Medieval Bridges. Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire: Shire Books. ISBN 978-0-7478-0384-3.

- Harrison, David (2007). The Bridges of Medieval England: Transport and Society, 400–1800. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-922685-6.

- Harrison, David; McKeague, Peter; Watson, Bruce (2010). "England's fortified medieval bridges and bridge chapels: a new survey" (PDF). Medieval Settlement Research. 25 (25): 45–51. doi:10.5284/1059045.

- Hayman, Richard (2020). Bridges. Oxford: Shire Books. ISBN 978-1-78442-387-2.

- Henderson, Charles; Jervoise, Edwyn (1938). Old Devon Bridges. Exeter: A. Wheaton & co. OCLC 13810767.

- McFetrich, David (2019). An Encyclopaedia of British Bridges (Revised and extended ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-5267-5295-6.

- Meller, Hugh (1989). Exeter Architecture. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 978-0-85033-693-1.

- Morris, Richard K. (2005). Roads: Archaeology and Architecture. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-2887-1.

- Orme, Nicholas (2014). The Churches of Medieval Exeter. Exeter: Impress Books. ISBN 978-1-907605-51-2.

- Otter, R. A. (1994). Civil Engineering Heritage: Southern England. London: Thomas Telford. ISBN 978-0-7277-1971-3.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Cherry, Bridget (2002). Devon. The Buildings of England. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09596-8.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Historic England. "The medieval Exe Bridge, St Edmund's Church, and medieval tenement remains, lying between the River Exe and Frog Street (1020671)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Brierley, p. 127.

- ^ Brown, pp. 4–5.

- ^ Cook, pp. 10–12.

- ^ a b Hayman, pp. 9–10.

- ^ Brierley, pp. 126–127.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Brierley. p. 130.

- ^ a b c Meller, p. 64.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, p. 62.

- ^ a b Harrison, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Brown, p. 6.

- ^ a b Brown, pp. 6–7.

- ^ a b c d Brown, pp. 8–9.

- ^ a b c d e f Brierley. p. 131.

- ^ a b c d e Harrison, p. 112.

- ^ McFetrich, p. 117.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, pp. 63–64.

- ^ a b c Brierley, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Brown, pp. 14–15.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, p. 63.

- ^ Harrison, p. 181.

- ^ a b Brierley, p. 136.

- ^ Brown, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Harrison, p. 159.

- ^ Brown, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Otter, p. 72.

- ^ Pevsner, p. 410.

- ^ Brown, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Brierley, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Otter, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Historic England. "Old Exe Bridge (1103988)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 January 2018.

- ^ Brierley, p. 139.

- ^ "About Exe Bridge, Exeter". Transport Trust. Retrieved 8 January 2019.

- ^ Brierley, pp. 138–139.

- ^ a b Brierley, pp. 137–138.

- ^ Morris, pp. 201–203.

- ^ a b c d Brown, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Brierley. p. 136.

- ^ Brierley, p. 133.

- ^ Hayman, p.11.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, p. 67.

- ^ Pevsner, p. 390.

- ^ Brierley, p. 135.

- ^ Henderson & Jervoise, p. 66.

- ^ Orme, pp. 169–172.

- ^ Historic England. "Church of St Thomas (1169954)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 3 October 2021.

- ^ Harrison, et al, p. 49.

- ^ Brown, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Brown, pp. 22–23.

Further reading

[edit]- Brown, Stewart (2019). The Medieval Exe Bridge, St Edmund's Church, and Excavation of Waterfront Houses, Exeter. Exeter: Devon Archaeological Society. ISBN 978-0-9527899-2-5.