Android (robot)

An android is a humanoid robot or other artificial being, often made from a flesh-like material.[1][2][3][4] Historically, androids existed only in the domain of science fiction and were frequently seen in film and television, but advances in robot technology have allowed the design of functional and realistic humanoid robots.[5][6]

Terminology

[edit]

The Oxford English Dictionary traces the earliest use (as "Androides") to Ephraim Chambers' 1728 Cyclopaedia, in reference to an automaton that St. Albertus Magnus allegedly created.[3][7] By the late 1700s, "androides", elaborate mechanical devices resembling humans performing human activities, were displayed in exhibit halls.[8] The term "android" appears in US patents as early as 1863 in reference to miniature human-like toy automatons.[9] The term android was used in a more modern sense by the French author Auguste Villiers de l'Isle-Adam in his work Tomorrow's Eve (1886), featuring an artificial humanoid robot named Hadaly.[3] The term made an impact into English pulp science fiction starting from Jack Williamson's The Cometeers (1936) and the distinction between mechanical robots and fleshy androids was popularized by Edmond Hamilton's Captain Future stories (1940–1944).[3]

Although Karel Čapek's robots in R.U.R. (Rossum's Universal Robots) (1921)—the play that introduced the word robot to the world—were organic artificial humans, the word "robot" has come to primarily refer to mechanical humans, animals, and other beings.[3] The term "android" can mean either one of these,[3] while a cyborg ("cybernetic organism" or "bionic man") would be a creature that is a combination of organic and mechanical parts.

The term "droid", popularized by George Lucas in the original Star Wars film and now used widely within science fiction, originated as an abridgment of "android", but has been used by Lucas and others to mean any robot, including distinctly non-human form machines like R2-D2. The word "android" was used in Star Trek: The Original Series episode "What Are Little Girls Made Of?" The abbreviation "andy", coined as a pejorative by writer Philip K. Dick in his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, has seen some further usage, such as within the TV series Total Recall 2070.[10]

While the term "android" is used in reference to human-looking robots in general (not necessarily male-looking humanoid robots), a robot with a female appearance can also be referred to as a gynoid. Besides one can refer to robots without alluding to their sexual appearance by calling them anthrobots (a portmanteau of anthrōpos and robot; see anthrobotics) or anthropoids (short for anthropoid robots; the term humanoids is not appropriate because it is already commonly used to refer to human-like organic species in the context of science fiction, futurism and speculative astrobiology).[11]

Authors have used the term android in more diverse ways than robot or cyborg. In some fictional works, the difference between a robot and android is only superficial, with androids being made to look like humans on the outside but with robot-like internal mechanics.[3] In other stories, authors have used the word "android" to mean a wholly organic, yet artificial, creation.[3] Other fictional depictions of androids fall somewhere in between.[3]

Eric G. Wilson, who defines an android as a "synthetic human being", distinguishes between three types of android, based on their body's composition:

- the mummy type – made of "dead things" or "stiff, inanimate, natural material", such as mummies, puppets, dolls and statues

- the golem type – made from flexible, possibly organic material, including golems and homunculi

- the automaton type – made from a mix of dead and living parts, including automatons and robots[4]

Although human morphology is not necessarily the ideal form for working robots, the fascination in developing robots that can mimic it can be found historically in the assimilation of two concepts: simulacra (devices that exhibit likeness) and automata (devices that have independence).

Projects

[edit]Several projects aiming to create androids that look, and, to a certain degree, speak or act like a human being have been launched or are underway.

Japan

[edit]This section needs expansion with: more recent examples and additional citations. You can help by adding to it. (October 2018) |

Japanese robotics have been leading the field since the 1970s.[12] Waseda University initiated the WABOT project in 1967, and in 1972 completed the WABOT-1, the first android, a full-scale humanoid intelligent robot.[13][14] Its limb control system allowed it to walk with the lower limbs, and to grip and transport objects with hands, using tactile sensors. Its vision system allowed it to measure distances and directions to objects using external receptors, artificial eyes and ears. And its conversation system allowed it to communicate with a person in Japanese, with an artificial mouth.[14][15][16]

In 1984, WABOT-2 was revealed, and made a number of improvements. It was capable of playing the organ. Wabot-2 had ten fingers and two feet, and was able to read a score of music. It was also able to accompany a person.[17] In 1986, Honda began its humanoid research and development program, to create humanoid robots capable of interacting successfully with humans.[18]

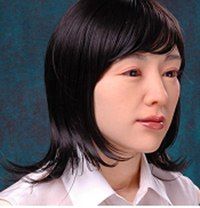

The Intelligent Robotics Lab, directed by Hiroshi Ishiguro at Osaka University, and the Kokoro company demonstrated the Actroid at Expo 2005 in Aichi Prefecture, Japan and released the Telenoid R1 in 2010. In 2006, Kokoro developed a new DER 2 android. The height of the human body part of DER2 is 165 cm. There are 47 mobile points. DER2 can not only change its expression but also move its hands and feet and twist its body. The "air servosystem" which Kokoro developed originally is used for the actuator. As a result of having an actuator controlled precisely with air pressure via a servosystem, the movement is very fluid and there is very little noise. DER2 realized a slimmer body than that of the former version by using a smaller cylinder. Outwardly DER2 has a more beautiful proportion. Compared to the previous model, DER2 has thinner arms and a wider repertoire of expressions. Once programmed, it is able to choreograph its motions and gestures with its voice.

The Intelligent Mechatronics Lab, directed by Hiroshi Kobayashi at the Tokyo University of Science, has developed an android head called Saya, which was exhibited at Robodex 2002 in Yokohama, Japan. There are several other initiatives around the world involving humanoid research and development at this time, which will hopefully introduce a broader spectrum of realized technology in the near future. Now Saya is working at the Science University of Tokyo as a guide.

The Waseda University (Japan) and NTT docomo's manufacturers have succeeded in creating a shape-shifting robot WD-2. It is capable of changing its face. At first, the creators decided the positions of the necessary points to express the outline, eyes, nose, and so on of a certain person. The robot expresses its face by moving all points to the decided positions, they say. The first version of the robot was first developed back in 2003. After that, a year later, they made a couple of major improvements to the design. The robot features an elastic mask made from the average head dummy. It uses a driving system with a 3DOF unit. The WD-2 robot can change its facial features by activating specific facial points on a mask, with each point possessing three degrees of freedom. This one has 17 facial points, for a total of 56 degrees of freedom. As for the materials they used, the WD-2's mask is fabricated with a highly elastic material called Septom, with bits of steel wool mixed in for added strength. Other technical features reveal a shaft driven behind the mask at the desired facial point, driven by a DC motor with a simple pulley and a slide screw. Apparently, the researchers can also modify the shape of the mask based on actual human faces. To "copy" a face, they need only a 3D scanner to determine the locations of an individual's 17 facial points. After that, they are then driven into position using a laptop and 56 motor control boards. In addition, the researchers also mention that the shifting robot can even display an individual's hair style and skin color if a photo of their face is projected onto the 3D Mask.

Singapore

[edit]Prof Nadia Thalmann, a Nanyang Technological University scientist, directed efforts of the Institute for Media Innovation along with the School of Computer Engineering in the development of a social robot, Nadine. Nadine is powered by software similar to Apple's Siri or Microsoft's Cortana. Nadine may become a personal assistant in offices and homes in future, or she may become a companion for the young and the elderly.

Assoc Prof Gerald Seet from the School of Mechanical & Aerospace Engineering and the BeingThere Centre led a three-year R&D development in tele-presence robotics, creating EDGAR. A remote user can control EDGAR with the user's face and expressions displayed on the robot's face in real time. The robot also mimics their upper body movements. [19]

South Korea

[edit]

KITECH researched and developed EveR-1, an android interpersonal communications model capable of emulating human emotional expression via facial "musculature" and capable of rudimentary conversation, having a vocabulary of around 400 words. She is 160 cm tall and weighs 50 kg, matching the average figure of a Korean woman in her twenties. EveR-1's name derives from the Biblical Eve, plus the letter r for robot. EveR-1's advanced computing processing power enables speech recognition and vocal synthesis, at the same time processing lip synchronization and visual recognition by 90-degree micro-CCD cameras with face recognition technology. An independent microchip inside her artificial brain handles gesture expression, body coordination, and emotion expression. Her whole body is made of highly advanced synthetic jelly silicon and with 60 artificial joints in her face, neck, and lower body; she is able to demonstrate realistic facial expressions and sing while simultaneously dancing. In South Korea, the Ministry of Information and Communication had an ambitious plan to put a robot in every household by 2020.[20] Several robot cities have been planned for the country: the first will be built in 2016 at a cost of 500 billion won (US$440 million), of which 50 billion is direct government investment.[21] The new robot city will feature research and development centers for manufacturers and part suppliers, as well as exhibition halls and a stadium for robot competitions. The country's new Robotics Ethics Charter will establish ground rules and laws for human interaction with robots in the future, setting standards for robotics users and manufacturers, as well as guidelines on ethical standards to be programmed into robots to prevent human abuse of robots and vice versa.[22]

United States

[edit]Walt Disney and a staff of Imagineers created Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln that debuted at the 1964 New York World's Fair.[23]

Dr. William Barry, an Education Futurist and former visiting West Point Professor of Philosophy and Ethical Reasoning at the United States Military Academy, created an AI android character named "Maria Bot". This Interface AI android was named after the infamous fictional robot Maria in the 1927 film Metropolis, as a well-behaved distant relative. Maria Bot is the first AI Android Teaching Assistant at the university level.[24][25] Maria Bot has appeared as a keynote speaker as a duo with Barry for a TEDx talk in Everett, Washington in February 2020.[26]

Resembling a human from the shoulders up, Maria Bot is a virtual being android that has complex facial expressions and head movement and engages in conversation about a variety of subjects. She uses AI to process and synthesize information to make her own decisions on how to talk and engage. She collects data through conversations, direct data inputs such as books or articles, and through internet sources.

Maria Bot was built by an international high-tech company for Barry to help improve education quality and eliminate education poverty. Maria Bot is designed to create new ways for students to engage and discuss ethical issues raised by the increasing presence of robots and artificial intelligence. Barry also uses Maria Bot to demonstrate that programming a robot with life-affirming, ethical framework makes them more likely to help humans to do the same.[27]

Maria Bot is an ambassador robot for good and ethical AI technology.[28]

Hanson Robotics, Inc., of Texas and KAIST produced an android portrait of Albert Einstein, using Hanson's facial android technology mounted on KAIST's life-size walking bipedal robot body. This Einstein android, also called "Albert Hubo", thus represents the first full-body walking android in history.[29] Hanson Robotics, the FedEx Institute of Technology,[30] and the University of Texas at Arlington also developed the android portrait of sci-fi author Philip K. Dick (creator of Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, the basis for the film Blade Runner), with full conversational capabilities that incorporated thousands of pages of the author's works.[31] In 2005, the PKD android won a first-place artificial intelligence award from AAAI.

Use in fiction

[edit]Androids are a staple of science fiction. Isaac Asimov pioneered the fictionalization of the science of robotics and artificial intelligence, notably in his 1950s series I, Robot.[32] One thing common to most fictional androids is that the real-life technological challenges associated with creating thoroughly human-like robots — such as the creation of strong artificial intelligence—are assumed to have been solved.[33] Fictional androids are often depicted as mentally and physically equal or superior to humans—moving, thinking and speaking as fluidly as them.[3][33]

The tension between the nonhuman substance and the human appearance—or even human ambitions—of androids is the dramatic impetus behind most of their fictional depictions.[4][33] Some android heroes seek, like Pinocchio, to become human, as in the film Bicentennial Man,[33] or Data in Star Trek: The Next Generation. Others, as in the film Westworld, rebel against abuse by careless humans.[33] Android hunter Deckard in Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? and its film adaptation Blade Runner discovers that his targets appear to be, in some ways, more "human" than he is.[33] The sequel Blade Runner 2049 involves android hunter K, himself an android, discovering the same thing. Android stories, therefore, are not essentially stories "about" androids; they are stories about the human condition and what it means to be human.[33]

One aspect of writing about the meaning of humanity is to use discrimination against androids as a mechanism for exploring racism in society, as in Blade Runner.[34] Perhaps the clearest example of this is John Brunner's 1968 novel Into the Slave Nebula, where the blue-skinned android slaves are explicitly shown to be fully human.[35] More recently, the androids Bishop and Annalee Call in the films Aliens and Alien Resurrection are used as vehicles for exploring how humans deal with the presence of an "Other".[36] The 2018 video game Detroit: Become Human also explores how androids are treated as second class citizens in a near future society.

Female androids, or "gynoids", are often seen in science fiction, and can be viewed as a continuation of the long tradition of men attempting to create the stereotypical "perfect woman".[37] Examples include the Greek myth of Pygmalion and the female robot Maria in Fritz Lang's Metropolis. Some gynoids, like Pris in Blade Runner, are designed as sex-objects, with the intent of "pleasing men's violent sexual desires",[38] or as submissive, servile companions, such as in The Stepford Wives. Fiction about gynoids has therefore been described as reinforcing "essentialist ideas of femininity",[39] although others have suggested that the treatment of androids is a way of exploring racism and misogyny in society.[40]

The 2015 Japanese film Sayonara, starring Geminoid F, was promoted as "the first movie to feature an android performing opposite a human actor".[41]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Van Riper, A. Bowdoin (2002). Science in popular culture: a reference guide. Westport: Greenwood Press. p. 10. ISBN 0-313-31822-0.

- ^ Prucher, Jeff (2007). "android". Brave New Words: The Oxford Dictionary of Science Fiction. Oxford University Press. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-19-530567-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Brian M. Stableford (2006). Science fact and science fiction: an encyclopedia. CRC Press. pp. 22–23. ISBN 978-0-415-97460-8.

- ^ a b c Eric G. Wilson (2006). The melancholy android: on the psychology of sacred machines. SUNY Press. pp. 27–28. ISBN 978-0-7914-6846-3.

- ^ McCaw, Caroline (2001). Http. [University of Otago?]. OCLC 225915408.

- ^ Ishiguro, Hiroshi. "Android science.", Cognitive Science Society, Osaka, 2005. Retrieved on 3 October 2013.

- ^ OED at "android" citing Ephraim Chambers, Cyclopædia; or, a universal dictionary of arts and sciences. 1728.

- ^ "At the Mechanical Theater". London Times. 22 December 1795.

- ^ "U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Patent# 40891, Toy Automation". Google Patents. Retrieved 7 January 2007.[dead link]

- ^ Levin, Drew S. (exec. prod.) (23 February 1999). "Rough Whimper of Insanity". Total Recall 2070. Season 1. Episode 7. Toronto. 2:10 minutes in. Channel Zero. CHCH-TV. Archived from the original on 5 February 2010.

- ^ "Anthrobotics: Where The Human Ends and the Robot Begins". Futurism. 7 March 2017. Retrieved 19 February 2022.

- ^ Zeghloul, Saïd; Laribi, Med Amine; Gazeau, Jean-Pierre (21 September 2015). Robotics and Mechatronics: Proceedings of the 4th IFToMM International Symposium on Robotics and Mechatronics. Springer. ISBN 9783319223681.

- ^ "Humanoid History -WABOT-". www.humanoid.waseda.ac.jp.

- ^ a b "Historical Android Projects". androidworld.com. Archived from the original on 25 November 2005. Retrieved 6 May 2017.

- ^ Robots: From Science Fiction to Technological Revolution, page 130

- ^ Duffy, Vincent G. (19 April 2016). Handbook of Digital Human Modeling: Research for Applied Ergonomics and Human Factors Engineering. CRC Press. ISBN 9781420063523.

- ^ "2history". Archived from the original on 12 October 2007. Retrieved 31 August 2007.

- ^ "P3". Honda Worldwide. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- ^ "NTU scientists unveil social and telepresence robots". Archived from the original on 3 September 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2015.

- ^ "A Robot in Every Home by 2020, South Korea Says". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 14 November 2006. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "South Korea set to build "Robot Land"". Engadget. 27 August 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Robot Code of Ethics to Prevent Android Abuse, Protect Humans". News.nationalgeographic.com. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 19 March 2007. Retrieved 22 November 2011.

- ^ "Pavilions & Attractions – Illinois – Page Two". Retrieved 23 March 2011.

- ^ "The Education of an Android Teacher – EdSurge News". 9 March 2020.

- ^ "First Android Teaching Assistant at NDNU | Media Center". Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "William Barry | tedxeverettcom". Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 15 March 2020.

- ^ "Maria Bot".

- ^ "Mesh conference announces AI robot as keynote speaker". 24 February 2020.

- ^ "(no title)". www.hansonrobotics.wordpress.com.

{{cite web}}: Cite uses generic title (help) - ^ "FIT – FedEx Institute of Technology – The University of Memphis". www.fedex.memphis.edu.

- ^ "about " PKD Android". www.pkdandroid.org. Archived from the original on 14 August 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2009.

- ^ Jonathan Barra, Roger Caille; et al. "The Android Generation". West Coast Midnight Run/Citadel Consulting Group LLC. Retrieved 9 February 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g Van Riper, op.cit., p. 11.

- ^ Dinello, Daniel (2005). Technophobia!: Science Fiction Visions of Posthuman Technology. University of Texas Press. p. 76. ISBN 9780292709867.

- ^ D'Ammassa, Don (2005). Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. Facts on File. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-8160-5924-9.

- ^ Nishime, LeiLani (Winter 2005). "The Mulatto Cyborg: Imagining a Multiracial Future". Cinema Journal. 44 (2). University of Texas Press: 34–49. doi:10.1353/cj.2005.0011.

- ^ Melzer, Patricia (2006). Alien Constructions: Science Fiction and Feminist Thought. University of Texas Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-292-71307-9.

- ^ Melzer, p. 204

- ^ Grebowicz, Margret; L. Timmel Duchamp; Nicola Griffith; Terry Bisson (2007). SciFi in the mind's eye: reading science through science fiction. Open Court. p. xviii. ISBN 978-0-8126-9630-1.

- ^ Dinello, op. cit., p 77.

- ^ James Hadfield (24 October 2015). "Tokyo: 'Sayonara' Filmmakers Debate Future of Robot Actors". variety.com. Retrieved 9 November 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Kerman, Judith B. (1991). Retrofitting Blade Runner: Issues in Ridley Scott's Blade Runner and Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Bowling Green, OH: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 0-87972-509-5.

- Perkowitz, Sidney (2004). Digital People: From Bionic Humans to Androids. Joseph Henry Press. ISBN 0-309-09619-7.

- Shelde, Per (1993). Androids, Humanoids, and Other Science Fiction Monsters: Science and Soul in Science Fiction Films. New York: New York University Press. ISBN 0-8147-7930-1.

- Ishiguro, Hiroshi. "Android science." Cognitive Science Society. 2005.

- Glaser, Horst Albert and Rossbach, Sabine: The Artificial Human, Frankfurt/M., Bern, New York 2011 "The Artificial Human"

- TechCast Article Series, Jason Rupinski and Richard Mix, "Public Attitudes to Androids: Robot Gender, Tasks, & Pricing"

- Carpenter, J. (2009). Why send the Terminator to do R2D2s job?: Designing androids as rhetorical phenomena. Proceedings of HCI 2009: Beyond Gray Droids: Domestic Robot Design for the 21st Century. Cambridge, UK. 1 September.

- Telotte, J.P. Replications: A Robotic History of the Science Fiction Film. University of Illinois Press, 1995.