Sita

| Sita | |

|---|---|

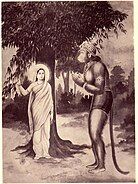

Lithograph of Sita in exile | |

| Other names | Siya, Janaki, Maithili, Vaidehi, Ayonija, Bhumija, Seetha |

| Devanagari | सीता |

| Sanskrit transliteration | Sītā |

| Venerated in | Ramanandi Sampradaya Niranjani Sampradaya Shaktism |

| Affiliation | Avatar of Lakshmi, Devi |

| Abode | |

| Mantra |

|

| Symbol | Pink Lotus |

| Day | Friday |

| Texts | |

| Gender | Female |

| Festivals |

|

| Genealogy | |

| Avatar birth | Mithila, Videha (either present-day Sitamarhi district, Bihar, India[5][6][7][8] or present-day Janakpur, Madhesh Province, Nepal[9][10][11]) |

| Avatar end | Baripur, Kosala (present-day Sita Samahit Sthal, Uttar Pradesh, India) |

| Parents | Bhumi (mother) Janaka (adoptive father) Sunayana (adoptive mother) |

| Siblings | Urmila (sister) Mandavi (cousin) Shrutakirti (cousin) |

| Consort | Rama |

| Children | Lava (son) Kusha (son) |

| Dynasty | Vidēha (by birth) Raghuvamsha-Suryavamsha (by marriage) |

| Part of a series on |

| Hinduism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

Sita (Sanskrit: सीता; IAST: Sītā), also known as Siya, Jānaki and Maithili, is a Hindu goddess and the female protagonist of the Hindu epic Ramayana. Sita is the consort of Rama, the avatar of god Vishnu, and is regarded as an avatar of goddess Lakshmi.[12] She is the chief goddess of the Ramanandi Sampradaya and is the goddess of beauty and devotion. Sita's birthday is celebrated every year on the occasion of Sita Navami.[13]

Described as the daughter of Bhūmi (the earth), Sita is brought up as the adopted daughter of King Janaka of Videha.[14][15] Sita, in her youth, chooses Rama, the prince of Ayodhya as her husband in a swayamvara. After the swayamvara, she accompanies her husband to his kingdom but later chooses to accompany him along with her brother-in-law Lakshmana, in his exile. While in exile, the trio settles in the Dandaka forest from where she is abducted by Ravana, the Rakshasa king of Lanka. She is imprisoned in the garden of Ashoka Vatika, in Lanka, until she is rescued by Rama, who slays her captor. After the war, in some versions of the epic, Rama asks Sita to undergo Agni Pariksha (an ordeal of fire), by which she proves her chastity, before she is accepted by Rama, which for the first time makes his brother Lakshmana angry at him.

In some versions of the epic, Maya Sita, an illusion created by Agni, takes Sita's place and is abducted by Ravana and suffers his captivity, while the real Sita hides in the fire. Some scriptures also mention her previous birth as Vedavati, a woman Ravana tries to molest.[16] After proving her purity, Rama and Sita return to Ayodhya, where they are crowned as king and queen. One day, a man questions Sita's fidelity and in order to prove her innocence and maintain his own and the kingdom's dignity, Rama sends Sita into the forest near the sage Valmiki's ashram. Years later, Sita returns to the womb of her mother, the Earth, for release from a cruel world and as a testimony to her purity, after she reunites her two sons Kusha and Lava with their father Rama.[17][18]

Etymology and other names

The goddess is best known by the name "Sita", derived from the Sanskrit word sīta, furrow.[19]

According to Ramayana, Janaka found her while ploughing as a part of a yagna and adopted her. The word Sīta was a poetic term, which signified fertility and the many blessings coming from settled agriculture. The Sita of the Ramayana may have been named after a more ancient Vedic goddess Sita, who is mentioned once in the Rigveda as an earth goddess who blesses the land with good crops. In the Vedic period, she was one of the goddesses associated with fertility. Rigveda 4.53.6, addressed to Agricultural Divinities, states

"Become inclined our way, well-portioned Furrow. We will extol you,

so that you will be well-portioned for us, so that you will be well-fruited for us."

-Translated by Jamison and Brereton[20]

In Harivamsa, Sita is invoked as one of the names of the goddess Arya:

O goddess, you are the altar's center in the sacrifice,

The priest's fee

Sita to those who hold the plough

And Earth to all living being.

The Kausik-sutra and the Paraskara-sutra associate her repeatedly as the wife of Parjanya (a god associated with rains) and Indra.[19]

Sita is known by many epithets. She is called Jānaki as the daughter of Janaka and Maithili as the princess of Mithila.[21] As the wife of Rama, she is called Ramā. Her father Janaka had earned the sobriquet Videha due to his ability to transcend body consciousness; Sita is therefore also known as Vaidehi.[21]

Legends

Birth and early life

The birthplace of Sita is disputed.[22] The Sita Kund[6] pilgrimage site which is located in present-day Sitamarhi district,[7][8] Bihar, India, is viewed as the birthplace of Sita. Apart from Sitamarhi, Janakpur, which is located in the present-day Province No. 2, Nepal,[23][24] is also described as Sita's birthplace.

- Other versions

- Janaka's biological daughter: In Ramopkhyana of the Mahabharata and also in Paumachariya of Vimala Suri, Sita has been depicted as Janaka's biological daughter. According to Rev. Fr. Camille Bulcke, this motif that Sita was the biological daughter of Janaka, as described in Ramopkhyana Mahabharata was based on the authentic version of Valmiki Ramayana. Later, the story of Sita miraculously appearing in a furrow was inserted in Valmiki Ramayana.[25]

- Ramayana Manjari: In Ramayana Manjari (verses 344–366), North-western and Bengal recensions of Valmiki Ramayana, it has been described as on hearing a voice from the sky and then seeing Menaka, Janaka expresses his wish to obtain a child, and when he finds the child, he hears the same voice again telling him the infant is his Spiritual child, born of Menaka.[25]

- Reincarnation of Vedavati: Some versions of the Ramayana suggest that Sita was a reincarnation of Vedavati. Ravana tried to molest Vedavati and her chastity was sullied beyond Ravana's redemption when she was performing penance to become the consort of Vishnu. Vedavati immolated herself on a pyre to escape Ravana's lust, vowing to return in another age and be the cause of Ravana's destruction. She was duly reborn as Sita.[25]

- Reincarnation of Manivati: According to Gunabhadra's Uttara Purana of the ninth century CE, Ravana disturbs the asceticism of Manivati, daughter of Amitavega of Alkapuri, and she pledges to take revenge on Ravana. Manivati is later reborn as the daughter of Ravana and Mandodari. But astrologers predicted the ruin of Ravana because of this child. So, Ravana gives orders to kill the child. Manivati is placed in a casket and buried in the ground of Mithila, where she is discovered by some of the farmers of the kingdom. Then Janaka, king of that state, adopts her.[25]

- Ravana's daughter: In Sanghadasa's Jaina version of Ramayana, and also in Adbhuta Ramayana, Sita, entitled Vasudevahindi, is born as the daughter of Ravana. According to this version, astrologers predict that the first child of Vidyadhara Maya (Ravana's wife) will destroy his lineage. Thus, Ravana abandons her and orders the infant to be buried in a distant land where she is later discovered and adopted by Janaka.[25]

Sita has a younger sister Urmila, born to Janaka and Sunayna, whom she was the closest among her three sisters.[26] Her father's younger brother, Kushadhvaja daughters Mandavi and Shrutakirti grew up with them in Mithila.[27]

Marriage to Rama

When Sita reached adulthood, Janaka conducted a svayamvara ceremony at his capital with the condition that she would marry only a prince who would possess the strength to string the Pinaka, the bow of the deity Shiva. Many princes attempted and failed to string the bow.[28] During this time, Vishvamitra had brought Rama and his brother Lakshmana to the forest for the protection of a yajna (ritual sacrifice). Hearing about the svayamvara, Vishvamitra asked Rama to participate in the ceremony with the consent of Janaka, who agreed to offer Sita's hand in marriage to the prince if he could fulfil the requisite task. When the bow was brought before him, Rama seized the centre of the weapon, fastened the string taut, and broke it in two in the process. Witnessing his prowess, Janaka agreed to marry his daughter to Rama and invited Dasharatha to his capital.[29]

King Dasharatha arrived in Mithila for his son's wedding and noticed that Lakshmana had feelings for Urmila, but according to tradition, Bharata and Mandavi were to marry first. He then arranged for Bharata to marry Mandavi and Shatrughna to marry Shrutakirti, allowing Lakshmana to marry Urmila. Ultimately, all four sisters married the four brothers, strengthening the alliance between the two kingdoms.[30] A wedding ceremony was conducted under the guidance of Shatananda. During the homeward journey to Ayodhya, another avatar of Vishnu, Parashurama, challenged Rama to combat, on the condition that he was able to string the bow of Vishnu, Sharanga. When Rama obliged him with success, Parashurama acknowledged the former to be a form of Vishnu and departed to perform penance at the mountain Mahendra. The wedding entourage then reached Ayodhya, entering the city amid great fanfare.[31][15]

Exile and abduction

Some time after the wedding, Kaikeyi, Rama's stepmother, compelled Dasharatha to make Bharata king, prompted by the coaxing of her maid Manthara, and forced Rama to leave Ayodhya and spend a period of exile in the forests of Dandaka and later Panchavati. Sita and Lakshmana willingly renounced the comforts of the palace and joined Rama in exile.[33] The Panchavati forest became the scene for Sita's abduction by Ravana, King of Lanka. The scene started with Shurpanakha's love for Rama. However Rama refused her, stating that he was devoted to Sita. This enraged the demoness and she tried to kill Sita. Lakshmana cut Shurpanakha's nose and sent her back. Ravana, to kidnap Sita, made a plan. Maricha, his uncle, disguised himself as a magnificent deer to lure Sita.[34] Sita, attracted to its golden glow asked her husband to make it her pet. When Rama and Lakshmana went far away from the hut, Ravana kidnapped Sita, disguising himself as a mendicant. Some versions of the Ramayana describe Sita taking refuge with the fire-god Agni, while Maya Sita, her illusionary double, is kidnapped by the demon-king. Jatayu, the vulture-king, tried to protect Sita but Ravana chopped off his wings. Jatayu survived long enough to inform Rama of what had happened.[35]

Ravana took Sita back to his kingdom in Lanka and she was held as a prisoner in one of his palaces. During her captivity for a year in Lanka, Ravana expressed his desire for her; however, Sita refused his advances.[36] Hanuman was sent by Rama to seek Sita and eventually succeeded in discovering Sita's whereabouts. Sita gave Hanuman her jewellery and asked him to give it to her husband. Hanuman returned across the sea to Rama.[37]

Sita was finally rescued by Rama, who waged a war to defeat Ravana. Upon rescue, Rama makes Sita undergo a trial by fire to prove her chastity. In some versions of the Ramayana, during this test the fire-god Agni appears in front of Rama and attests to Sita's purity, or hands over to him the real Sita and declares it was Maya Sita who was abducted by Ravana.[35] The Thai version of the Ramayana, however, tells of Sita walking on the fire, of her own accord, to feel clean, as opposed to jumping in it. She is not burnt, and the coals turn to lotuses.[38]

Later years and second exile

In the Uttara Kanda, following their return to Ayodhya, Rama was crowned as the king with Sita by his side.[39][40] While Rama's trust and affection for Sita never wavered, it soon became evident that some people in Ayodhya could not accept Sita's long captivity under Ravana. During Rama's period of rule, an intemperate washerman, while berating his wayward wife, declared that he was "no pusillanimous Rama who would take his wife back after she had lived in the house of another man". The common folk started gossiping about Sita and questioned Ram's decision to make her queen. Rama was extremely distraught on hearing the news, but finally told Lakshmana that as a king, he had to make his citizens pleased and the purity of the queen of Ayodhya has to be above any gossip and rumour. With a heavy heart, he instructed him to take Sita to a forest outside Ayodhya and leave her there.[41]

Thus Sita was forced into exile a second time. Sita, who was pregnant, was given refuge in the hermitage of Valmiki, where she delivered twin sons named Kusha and Lava.[15] In the hermitage, Sita raised her sons alone, as a single mother.[42] They grew up to be valiant and intelligent and were eventually united with their father. Once she had witnessed the acceptance of her children by Rama, Sita sought final refuge in the arms of her mother Bhūmi. Hearing her plea for release from an unjust world and from a life that had rarely been happy, the Earth dramatically split open; Bhūmi appeared and took Sita away.

According to the Padma-puran, Sita's exile during her pregnancy was because of a curse during her childhood.[43] Sita had caught a pair of divine parrots, which were from Valmiki's ashram, when she was young. The birds were talking about a story of Sri Ram heard in Valmiki's ashram, which intrigued Sita. She has the ability to talk with animals. The female bird was pregnant at that time. She requested Sita to let them go, but Sita only allowed her male companion to fly away, and the female parrot died because of the separation from her companion. As a result, the male bird cursed Sita that she would suffer a similar fate of being separated from her husband during pregnancy. The male bird was reborn as the washerman.[44]

Speeches and symbolism

While the Ramayana mostly concentrates on Rama's actions, Sita also speaks many times during the exile. The first time is in the town of Chitrakuta where she narrates an ancient story to Rama, whereby Rama promises to Sita that he will never kill anybody without provocation.[45]

The second time Sita is shown talking prominently is when she speaks to Ravana. Ravana has come to her in the form of a mendicant and Sita tells him that he does not look like one.[46][47]

Some of her most prominent speeches are with Hanuman when he reaches Lanka. Hanuman wants an immediate union of Rama and Sita and thus he proposes to Sita to ride on his back. Sita refuses as she does not want to run away like a thief; instead she wants her husband Rama to come and defeat Ravana to save her.[48]

A female deity of agricultural fertility by the name Sita was known before Valmiki's Ramayana, but was overshadowed by better-known goddesses associated with fertility. According to Ramayana, Sita was discovered in a furrow when Janaka was ploughing. Since Janaka was a king, it is likely that ploughing was part of a royal ritual to ensure fertility of the land. Sita is considered to be a child of Mother Earth, produced by union between the king and the land. Sita is a personification of Earth's fertility, abundance, and well-being.[49]

In the Ramcharitmanas, Tulsidas called Sita the regulator of the universe and added,

"I bow to Sita, the beloved consort of Sri Rama, who is responsible for the creation, sustenance, and dissolution (of the universe), removes afflictions and begets all blessings."

— Balkand, Manglacharan, Shloka 5[50]

Literature

Sita is an important goddess in the Vaishnavite traditions of Hinduism. Regarded as the avatara of goddess Lakshmi, she is mentioned in various scriptures and text of Hindu traditions. Sita is the primary character of the minor Upanishad Sita Upanishad,[51] which is attached to the Atharva Veda.[52][53] The text identifies Sita with primordial Prakriti (nature) and her three powers are manifested in daily life as will (iccha), action (kriyā) and knowledge (jnana).[54][55]

Sita appears in the Puranas namely the Vishnu Purana and Padma Purana (as an avatar of Lakshmi),[56][57] the Matsya Purana (as form of Devi), the Linga Purana (as form of Lakshmi), the Kurma Purana,Agni Purana, Garuda Purana (as consort of Rama), the Skanda Purana and the Shiva Purana.[58][59] She also finds mention in the Vana Parva of the Mahabharata.[60]

Sita along with Rama appears as the central character in Valmiki Samhita, which is attributed to their worship and describes them to be the ultimate reality.[61][62] In its chapter 5, a dialogue form between Sita and saptarishi, described to Parvati by Shiva is mentioned, known as the Maithili Mahopanishad.[63]

भूर्भुवः स्वः । सप्तद्वीपा वसुमती । त्रयो लोकाः । अन्तरिक्षम् । सर्वे त्वयि निवसन्ति । आमोदः । प्रमोदः । विमोदः । सम्मोदः । सर्वांस्त्वं सन्धत्से । आञ्जनेयाय ब्रह्मविद्या प्रदात्रि धात्रित्वां सर्वे वयं प्रणमामहे प्रणमामहे ॥

The sages said: "In the earthly realm, the celestial space, and the heavenly realms, and in the seven continents on Earth, in the three worlds—heaven, mortal, and the netherworld. All these, including space and the sky, reside within you. You embody joy, delight, exhilaration, and bliss. Oh ultimate embodiment of Dhatrī! bestower of the Brahmavidya to Lord Hanuman! Oh sustainer of all realms, Sri Sita! We bow to you repeatedly."[64]

Apart from other versions of Ramayana, many 14th-century Vaishnava saints such as Nabha Dass, Tulsidas and Ramananda have mentioned Sita, in their works.[65] While Ramananda's Sri Ramarchan Paddati explains the complete procedure to worship Sita-Rama, Tulsidas's Vinaya Patrika has devotional hymns dedicated to her.[66][67] Ramananda through his conversation with disciple Surasurananda in Vaishnava Matabja Bhaskara, explains about the worship of Rama, Sita and Lakshmana. Kalidasa's Raghuvamsa gives a detail account of Sita's swayamvara, abduct and her exile, in the cantos 10 to 15.[68][69]

Sita and Radha

The Sita-Rama and Radha-Krishna pairs represent two different personality sets, two perspectives on dharma and lifestyles, both cherished in the way of life called Hinduism.[70] Sita is traditionally wedded: the dedicated and virtuous wife of Rama, an introspective temperate paragon of a serious, virtuous man.[71][72] Radha is a power potency of Krishna, who is a playful adventurer.[73][70]

Sita and Radha offer two templates within the Hindu tradition. If "Sita is a queen, aware of her social responsibilities", states Pauwels, then "Radha is exclusively focused on her romantic relationship with her lover", giving two contrasting role models from two ends of the moral universe. Yet they share common elements as well. Both face life challenges and are committed to their true love. They are both influential, adored and beloved goddesses in the Hindu culture.[70]

In worship of Rama, Sita is represented as a dutiful and loving wife, holding a position entirely subordinate to Rama. However, in the worship of Radha Krishna, Radha is often preferred over to Krishna, and in certain traditions, her name is elevated to a higher position compared to Krishna's.[74]

In other versions

Janaki Ramayana

The Janaki Ramayana is written by Pandit Lal Das. In this poetic form version, Sita is the central character of the epic.[75] The life of Goddess Sita and her infinite powers have been described from the beginning to the end. There are three Khandas in the Janaki Ramayana: Kathārambha, Lakshmikaanda and Radhakaanda.[76]

Adbhut Ramayana

The Adbhuta Ramayana is written by Valmiki himself and is shorter than the original epic. Sita is accorded far more prominence in this variant of the Ramayana narrative.[77] During the war, Sahastra Ravana shot an arrow at Rama, making him wounded and unconscious on the battle field. Seeing Rama unconscious and helpless on the field, Sita gives up her human appearance and takes the horrific form of Mahakali. In less than a second, she severed Sahastra Ravana's 1000 heads and began destroying rakshasas everywhere. Sita is eventually pacified by the gods, Rama's consciousness is restored and the story moves forward.[78]

Mahaviracharita

The Sanskrit play Mahaviracharita by Bhavabhuti is based on the early life of Rama. According to the play, Vishwamitra invites Janaka to attend his sacrifice, but he sends his brother Kushadhvaja and daughters Sita and Urmila, as his delegates. This is the place, where Rama and Sita met for the first time. By the end of the act, Kushadhvaja and Vishwamitra decide to marry Sita and Urmila to Rama and Lakshamana.[79]

Saptakanda Ramayana

Saptakanda Ramayana written by Madhava Kandali is a version of Ramayana known for its non-heroic portrayal of Rama, Sita, and other characters, which rendered the work unsuitable for religious purposes.[80]

Iconography

Sita in Hinduism, is revered as the goddess of beauty and devotion. She is mostly depicted along with her husband Rama and is shakti or prakriti of Rama, as told in the Ram Raksha Stotram. Mithila art, which originated at Sita's birthplace depicts Sita and Rama's marriage ceremony through the paintings.[81]

In Rama and Sita's temple, she is always placed on Rama's right, with a golden-yellow complexion.[82] She is dressed in traditional sari or ghagra-choli along with a veil. Her jewelry is either made of metals, pearls or flowers.[83]

Who is Sita?

सा देवी त्रिविधा भवति शक्त्यासना

इच्छाशक्तिः क्रियाशक्तिः साक्षाच्छक्तिरिति

That divine Being is threefold,

through her power, namely,

the power of desire,

the power of action,

the power of knowledge.

In the Ramayana, Sita is mostly depicted in saris and is called ethereal and divine. Praising her beauty in the Aranya Kanda, Ravana stated,

"Oh, rosy faced one, are you the personified numen of respect, renown or resplendence, or the felicitous Lakshmi herself, or oh, curvaceous one, are you a nymphal Apsara, or the numen of benefactress, or a self-motivated woman, or Rati devi, the consort of Manmatha, the Love God."[86]

The Sanskrit text and a minor Upanishad, Sita Upanishad describes Sita as the ultimate reality of the universe (Brahman), the ground of being (Spirituality), and material cause behind all manifestation.[87][88] Sita, in many Hindu mythology, is the Devi associated with agriculture, fertility, food and wealth for continuation of humanity.[89]: 58, 64

Outside Hinduism

Jainism

Sita is the daughter of King Janak and Queen Videha of Mithalapuri. She has a brother named Bhamandal who is kidnapped soon after his birth by a deity due to animosity in a previous life. He is thrown into a garden of Rathnupur where he is dropped into the arms of King Chandravardhan of Rathnupur. The king and queen bring him up as their own son. Ram and Sita get married due to Bhamandal and in the course of events Bhamandal realises that Sita is his sister. It is then that he meets his birth parents.[90][91]

Buddhism

The Dasaratha Jataka, a Jataka tale found in Buddhist literature describes Rama, Sita and Lakshmana as siblings. They are not banished but sent away to the Himalayas by King Dasaratha in order to protect them from their jealous stepmother, the only antagonist. When things have cooled down, Rama and Sita return to Benaras – and not Ayodhya – and get married.[92][93]

Portrayal and assessment

In Hinduism, Sita is revered as the goddess. She has been portrayed as an ideal daughter, an ideal wife and an ideal mother in various texts, stories, illustrations, movies and modern media.[94][95] Sita is often worshipped with Rama as his consort. The occasion of her marriage to Rama is celebrated as Vivaha Panchami. The actions, reactions, and instincts manifested by Sita at every juncture in a long and arduous life are deemed exemplary. Her story has been portrayed in the book Sitayanam.[96] The values that she enshrined and adhered to at every point in the course of a demanding life are the values of womanly virtue held sacred by countless generations of Indians.[12][97]

Ananda W. P. Guruge opined that Sita was the central theme of the epic. He called her a dedicated wife and noted, "Sita's adamant wish to accompany Rāma to the forest despite the discomforts and dangers is another proof of the sincere affection the wife had for her husband."[98] Sita has been considered as an equal partner to Rama. Known for her feminine courage, she is often been cited as one of the defining figures of Indian womanhood. Throughout her life, Sita has taken crucial decisions such as accompanying Rama to exile or protecting her dignity in Ashoka Vatika.[99]

Sita's character and life has significant influence on modern women. On this, Malashri Lal, the co-editor of In Search of Sita: Revisiting Mythology noted, "Modern-day women continue to see themselves reflected in films, serials, and soap operas based on Sita's narrative. She has been portrayed as a "folk heroine" in several Maithili songs and continue being a primary figure for women through folktales."[99] Assessing Sita's personality, Anju P. Bhargava stated,

"Sita, conjures up an [image] of a chaste pati vrata [dutiful wife] woman, the ideal woman. Some see her as victimized and oppressed who obeyed her husband's commands, remained faithful to him, served her in-laws or yielded to parental authority. Yet, there are others who see a more liberated Sita, who was outspoken, had the freedom to express herself, said what she wanted to in order to get her way, spoke harsh words, repented for it, loved her husband, was faithful to him, served her family, did not get seduced by the glamour and material objects in Lanka, faced an angry husband, tried to appease him, reconciled her marriage, later accepted her separation, raised well balanced children as a single mother and then moved on."[100]

Temples

Although Sita's statue is always kept with Rama's statue in Rama temples, there are some temples dedicated to Sita:

- Janaki Mandir, located at Janakpur, Nepal.[101]

- Janaki Janmasthali Mandir, Janaki Dham, situated in Sitamarhi district in Bihar, India.[102][103]

- Sita Kund, Punaura Dham, situated in Sitamarhi district in Bihar, India.[104]

- Sita Charan Mandir, Zaffar Nagar, India

- Seetha Devi Temple, Pulpally in the Wayanad district, Kerala, India.[105]

- Seetha Amman Temple, Nähe Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka.[106][107]

- Ponkuzhi Sita Temple, Muthanga, Kerala.[108]

- Sree Seetha Devi Lava-Kusha Temple, Irulam, Kerala.

- Sita Temple, Phalswari, Pauri district, Uttarakhand, India (Proposed).[109]

- Sita Mai Temple, situated in Sitamai village in the Karnal district of Haryana, India.

- Sita Samahit Sthal, situated in Bhadohi district in Uttar Pradesh, India.

- Sita Temple, situated in Yavatmal district in Maharashtra, India.[110]

- Urvija Kund, situated in Sitamarhi district in Bihar, India.[111]

- Sita Ki Rasoi, situated in Ayodhya district in Uttar Pradesh, India.[112]

-

Janaki Mandir of Janakpur, Nepal is a center of pilgrimage where the wedding of Sri Rama and Sita took place and is re-enacted yearly as Vivaha Panchami.

-

Seetha Amman Kovil, Nähe Nuwara Eliya, Sri Lanka.

Worship and festivals

As part of the Bhakti movement, Rama and Sita became the focus of the Ramanandi Sampradaya, a sannyasi community founded by the 14th-century North-Indian poet-saint Ramananda. This community has grown to become the largest Hindu monastic community in modern times.[113][114][115] Sita is also the supreme goddess in the Niranjani Sampradaya, that primarily worships Rama and Sita.[116]

Prajapati describes Sita as primal Prakriti, or primordial nature.[117][84] She is, asserts the text, same as Lakshmi and the Shakti (energy and power) of Vishnu.[84][118] She represents the vocal form of the four Vedas, which the text asserts comes from 21 schools of Rigveda, 109 schools of Yajurveda, 1000 schools of Samaveda, and 40 schools of Atharvaveda.[84] Sita is Lakshmi, seated as a Yogini on her lion throne,[119] and she personifies three goddesses: Shri (goddess of prosperity, Lakshmi), Bhumi (mother earth), and Nila (goddess of destruction).[55][120]

Hymns

List of prayers and hymns dedicated to Sita are:

- Jai Siya Ram – Greeting or Salutation in North India dedicated to Sita and Rama.[121]

- Siyavar Ramchandraji Ki Jai – Greeting or Salutation dedicated to Sita and Rama. The hymns introduces Rama as Sita's husband.

- Sita-Ram-Sita-Ram – The maha-mantra is as follows:

सीता राम सीता राम सीता राम जय सीता राम। सीता राम सीता राम सीता राम जय सीता राम।।

- Hare Rama Rama Rama, Sita Rama Rama Rama.

- Sita Kavacha – The hymn dedicated to Sita, mentioned in the Manohar Kanda of Ananda Ramayana.[122]

- Vinaya Patrika – The devotional poem has prayers dedicated to Sita.[123]

- Janaki Mangal – This verse describes the episode of Sita and Rama's marriage and has hymns and prayers dedicated to them.[124]

Festivals

Sita Navami

Sita Navami is a Hindu festival that celebrates the birth of the goddess Sita, one of the most popular deities in Hinduism, and an incarnation of the goddess Lakshmi. It is celebrated on the navami (ninth day) of the Shukla Paksha (first lunar fortnight) of the Hindu month of Vaishakha.[125] Sita is revered for her loyalty, devotion and sacrifice to her husband. She is considered the epitome of womanhood and is regarded as the ideal wife and mother in the Indian subcontinent.[126] It celebrates the anniversary date of the appearance or manifestation of Sita. On the occasion of Sita Navami, married women fast for their husbands's long life.[127][128]

Vivaha Panchami

Vivaha Panchami is a Hindu festival celebrating the wedding of Rama and Sita in the Janakpurdham which was the capital city of Mithila. It is observed on the fifth day of the Shukla paksha or waxing phase of moon in the Agrahayana month (November – December) as per the Bikram Samvat calendar and in the month of Mangsir.[129] The day is observed as the Vivaha Utsava of Sita and Rama in temples and sacred places associated with Rama, such as the Mithila region of Bihar, India, Nepal and Ayodhya of India.[130][131]

Ramlila and Dussehra

Rama and Sita's life is remembered and celebrated every year with dramatic plays and fireworks in autumn. This is called Ramlila, and the play follows the Ramayana or more commonly the Ramcharitmanas.[132] It is observed through thousands of Rama-related performance arts and dance events, that are staged during the festival of Navratri in India.[133] After the enactment of the legendary war between Good and Evil, the Ramlila celebrations climax in the Dussehra (Dasara, Vijayadashami) night festivities where the giant grotesque effigies of Evil such as of demon Ravana are burnt, typically with fireworks.[134]

The Ramlila festivities were declared by UNESCO as one of the "Intangible Cultural Heritages of Humanity" in 2008.[135] Ramlila is particularly notable in historically important Hindu cities of Ayodhya, Varanasi, Vrindavan, Almora, Satna and Madhubani – cities in Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh. The epic and its dramatic play migrated into southeast Asia in the 1st millennium CE, and Ramayana based Ramlila is a part of performance arts culture of Indonesia, particularly the Hindu society of Bali, Myanmar, Cambodia and Thailand.[136][137]

Diwali

In some parts of India, Rama and Sita's return to Ayodhya and their coronation is the main reason for celebrating Diwali, also known as the Festival of Lights.[138]

Vasanthotsavam

Vasanthotsavam is an annual Seva celebrated in Tirumala to celebrate the arrival of spring season.[139] Abhishekam – specifically called Snapana Thirumanjanam (Holy bathing), is performed to the utsava murthy and his consorts on all the three days. On the third day, abhishekam is performed to the idols of Rama, Sita, Lakshmana and Hanumana along with Krishna and Rukmini. Procession of the consecrated idols are taken in a procession in the evening on all the three days.[140]

Outside the Indian subcontinent

Indonesia

In the Indonesian version, especially in Javanese wayang stories. Sita in Indonesia is called Rakyan Wara Sinta or Shinta. Uniquely, she is also referred to as Ravana's own biological daughter, the Javanese version of Ravana is told that he fell in love with a female priest named Widawati. However, Widawati rejected his love and chose to commit suicide. Ravana was determined to find and marry the reincarnation of Widawati.[141]

On the instructions of his teacher, Resi Maruta, Rahwana learns that Widawati will incarnate as his own daughter. But when his wife named Dewi Kanung gave birth, Ravana went to expand the colony. Wibisana took the baby girl who was born by Kanung to be dumped in the river in a crate. Wibisana then exchanged the baby with a baby boy she had created from the sky. The baby boy was finally recognized by Ravana as his son, and later became known as Indrajit. Meanwhile, the baby girl who was dumped by Wibisana was carried by the river to the territory of the Mantili Kingdom. The king of the country named Janaka took and made her an adopted daughter, with the name Shinta.[142]

The next story is not much different from the original version, namely the marriage of Shinta to Sri Rama, her kidnapping, and the death of Ravana in the great war. However, the Javanese version says, after the war ended, Rama did not become king in Ayodhya, but instead built a new kingdom called Pancawati. From her marriage to Rama, Sinta gave birth to two sons named Ramabatlawa and Ramakusiya. The first son, namely Ramabatlawa, brought down the kings of the Mandura Kingdom, including Basudeva, and also his son, Krishna.[143]

The Javanese version of Krishna is referred to as the reincarnation of Rama, while his younger brother, Subhadra, is referred to as the reincarnation of Shinta. Thus, the relationship between Rama and Shinta, who in the previous life was husband and wife, turned into brother and sister in the next life.[144][145]

Wayang story

Shinta is the daughter of an angel named Batari Tari or Kanun, the wife of Ravana. Shinta is believed to be the incarnation of Btari Widawati, the wife of Lord Vishnu. In the seventh month, Kanun who was "mitoni" her pregnancy, suddenly caused a stir in the Alengka palace, because the baby he was carrying was predicted by several priests who were at the party that he would become Rahwana's "wife" (his own father). Ravana was furious. He rose from his throne and wanted to behead Kanun. But before it was realized, Ravana suddenly canceled his intention because he thought who knew his child would become a beautiful child. Thus, she too will be willing to marry him. Sure enough, when Ravana was on an overseas service, his empress gave birth to a baby girl with a very beautiful face glowing like the full moon. Wibisana (Ravana's sister) who is holy and full of humanity, immediately took the baby and put it in Sinta's diamond, then anchored it into the river. Only God can help him, that's what Wibisana thought. He immediately made the black mega cloud into a baby boy who would later be named Megananda or Indrajit.[146]

Syahdan a hermit named Prabu Janaka from the land of Mantili, begged the gods to be blessed with offspring. So surprised when he opened his eyes, he heard the cry of a baby in a sinking ketupat floating in the river. The baby was taken with pleasure and brought home adopted as his son. Because the baby is known to be in the diamond Sinta, then he was given the name Sinta. After being 17 years old, Sinta made a commotion all the youth, both domestic and foreign cadets because of her beauty.[147]

One day, a contest was held. Anyone who can draw the giant bow of Mantili's national heritage will become Sinta's mate. Ramawijaya, who was studying at the Brahmin Yogiswara, was advised to take part in the contest. Of course, Rama was successful, because he was the incarnation of Vishnu. Engagements and marriages are all enlivened with debauchery, both in the country of Mantili and in Ayodya. But luck was not good for both of them, while enjoying their honeymoon, suddenly the crown belonged to Kekayi, Rama's stepmother.

Dasarata Mr. Rama was ordered to hand over the crown to Bharata (Rama's younger brother). In addition, Rama, Sinta and Laksmana had to leave the palace into the wilderness for 13 years. In exile in the jungle, Sinta is unable to contain her desire to control the tempting Kijang Kencana, which someone who is concerned should not have. What was sparkling, at first he thought would make him happy, but on the contrary. Not only can Kijang Kencana be caught, but moreover he is captured and held captive by his own lust, which is manifested in the form of Ravana. Briefly he was diruda paripaksa, put in a gold cage in Alengka for about 12 years.[148]

One time, Raden Ramawijaya was defeated by Raden Ramawijaya, until Dewi Shinta was freed from Ravana's shackles. However, Shinta's suffering did not end there. After being released, she was still suspected of her chastity by her own husband Ramawijaya. So, to show that as long as in the reign of the King of Alengka, Sinta has not been stained, Shinta proves herself by plunging into the fire. Shinta was saved from the raging fire by the gods of heaven.[149][150]

Cambodia

Sita is referred to as Neang Seda in the Cambodian version Reamker.[151] While the story is similar to the original epic, there are two difference. Firstly, Rama married Sita, by completing the challenge of firing arrows through a spinning wheel with spokes. Later, Neang Seda (Sita) leave for the forest immediately after passing the test, as she is deeply offended by her husband's lack of trust in her and his lack of belief in her word.[152]

Nepal

Nepal's Janakpur is considered to be Sita's birthplace, other than Bihar's Sitamarhi. Sita is one of the eighteen national heroes (rastriya bibhuti) of Nepal.[153]

In other countries

Sita is referred to as the following, in different versions of Ramayana:

- Nang Sida, who embodies purity and fidelity – Ramakien, Thailand.[154]

- Towan Potri Malano Tihaya, or Potri Malayla Ganding, the princess of Polo Nabanday – Maharadia Lawana, Philippines.

- Siti Dewi, adoptive daughter of Maharisi Kali – Hikayat Seri Rama, Malaysia.[155]

- Nang Sida, incarnation of Nang Souxada – Phra Lak Phra Ram, Laos.[156]

Influence and depiction

Paintings

Rama and Sita have inspired many forms of performance arts and literary works.[157] Madhubani paintings are charismatic art of Bihar, and are mostly based on religion and mythology. In the paintings, Hindu gods like Sita-Rama are in center with their marriage ceremony being one of the primary theme.[81] Sita's abduction and her days in Lanka have also been depicted in the Rajput paintings.[158]

Music

Sita is a primary figure in Maithili music, of the Mithila region. The folk music genre Lagan, mentions about the problems faced by Rama and Sita during their marriage.[160][161]

Dance and art forms

The Ramayana became popular in Southeast Asia from the 8th century onward and was represented in literature, temple architecture, dance and theatre.[162] Dramatic enactments of the story of the Ramayana, known as Ramlila, take place all across India and in many places across the globe within the Indian diaspora.[163]

In Indonesia, especially Java and Bali, Ramayana has become a popular source of artistic expression for dance drama and shadow puppet performances in the region. Sendratari Ramayana is the Javanese traditional ballet in wayang orang style, routinely performed in the cultural center of Yogyakarta.[164][165] In Balinese Hindu temples in Ubud and Uluwatu, where scenes from Ramayana are an integral part of kecak dance performances.[166][167]

Culture

In the North Indian region, mainly in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, people use salutations such as Jai Shri Ram, Jai Siya Ram[168] and Siyavar Ramchandraji Ki Jai.[169] Photojournalist Prashant Panjiar wrote about how in the city Ayodhya female pilgrims always chant "Sita-Ram-Sita-Ram".[169] Ramanandi ascetics (called Bairagis) often use chants like "Jaya Sita Ram" and "Sita Ram".[170][171] The chants of Jai Siya Ram is also common at religious places and gatherings, for example, the Kumbh Mela.[172][173] It is often used during the recital of Ramayana, Ramcharitmanas, especially the Sundara Kanda.[174] Writer Amish Tripathi opines that "Shri" in Jai Shri Ram means Sita. He added,

We say Jai Shri Ram or Jai Siya Ram. Lord Ram and Goddess Sita are inseparable. When we worship Lord Ram, we worship Sita as well. We learn from Lord Ram, we learn from Goddess Sita as well. Traditionally, when you say Jai Shri Ram, Shri means Sita. Sita is the avatar of Goddess Laxmi and referred to as Shri. So, that's the way to see it. It's an equal partnership."[175]

In popular culture

Sita's story and sacrifice have inspired "painting, film, novels, poems, TV serials and plays". Prominently, she is depicted in all the adaptations of Ramayana.[176]

Films

The following people portrayed Sita in the film adaptation of Ramayana.[177]

- Durga Khote portrayed her in the 1934 Bengali film Seeta.[178]

- Shobhna Samarth portrayed her in the 1943 Hindi film Ram Rajya.

- Padmini portrayed her in the 1958 Tamil film Sampoorna Ramayanam.

- Kusalakumari portrayed her in the 1960 Malayalam film Seeta.

- Anjali Devi portrayed her in the 1968 Telugu film Veeranjaneya.

- Sridevi portrayed her in the 1976 Tamil film Dasavatharam.

- Smitha Madhav portrayed her in the 1997 Telugu film Ramayanam.[179]

- Jaya Prada portrayed her in the 1997 Hindi film Lav Kush.[180]

- Rael Padmasee and Namrata Sawhney voiced her in the 1992 animated film Ramayana: The Legend of Prince Rama.

- Juhi Chawla voiced her in the 2010 animated Hindi film Ramayana: The Epic.[181]

- Nayanthara portrayed her in the 2011 Telugu film Sri Rama Rajyam.[182]

- Kriti Sanon portrayed her in the 2023 Hindi film Adipurush.[183]

Television

The following people portrayed Sita in the television adaptation of Ramayana.

- Dipika Chikhlia portrayed her in the 1987 series Ramayan and the 1998 series Luv Kush.[184]

- Shilpa Mukherjee / Meenakshi Gupta portrayed her in the 1997 series Jai Hanuman.

- Reena Kapoor portrayed her in the 2000 series Vishnu Puran.

- Smriti Irani portrayed her in the 2002 series Ramayan.

- Debina Bonnerjee portrayed her in the 2008 series Ramayan.

- Reena Shah voiced her in the 2008 America animated series Sita Sings the Blues. Annette Hanshaw sang for her in the series songs.[185]

- Rubina Dilaik portrayed her in the 2011 series Devon Ke Dev...Mahadev.[186]

- Neha Sargam portrayed her in the 2012 series Ramayan.

- Richa Pallod portrayed her in the 2012 mini-series Ramleela – Ajay Devgn Ke Saath. Madhushree voiced for her in the song, "Jaao Na Morey Piya".

- Deblina Chatterjee portrayed her in the 2015 series Sankat Mochan Mahabali Hanumaan.

- Madirakshi Mundle portrayed her in the 2015 series Siya Ke Ram and the 2022 series Jai Hanuman – Sankatmochan Naam Tiharo.[187]

- Shivya Pathania portrayed her in the 2019 series Ram Siya Ke Luv Kush.[188]

- Aishwarya Ojha portrayed her in the 2021 web series Ramyug.[189]

- Prachi Bansal portrayed her in the 2024 series Shrimad Ramayan.[190]

- Vaibhavi Kapoor portrayed her in the 2024 series Kakabhushundi Ramayan- Anasuni Kathayein.

Plays

The following plays portrayed Sita's life in the theatre adaptation of Ramayana.

- Sita is the central character in the 1955 play, Bhoomikanya Sita, written by Bhargavaram Viththal Varerkar.[191]

- Her life struggles were also portrayed in the "Sita-Rama episode" of the 2023 play, Prem Ramayan.[192]

Books

The following novels talks about Sita's life.

- In Search of Sita: Revisiting Mythology by Namita Gokhale, published in 2009.[193]

- Sita's Ramayana by Samhita Arni and Moyna Chitrakar, published in 2011.[194]

- Sita – An Illustrated Retelling of the Ramayana by Devdutt Pattanaik, published in 2013.[195]

- Bhumika: A Story of Sita by Aditya Iyengar, published in 2019.[196]

- The Forest of Enchantments by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni, published in 2019.[197]

- Sita: A Tale of Ancient Love by Bhanumathi Narasimhan, published in 2021.[198]

- Sita: Warrior of Mithila by Amish Tripathi, published in 2022.[199]

Others

- Shri Ram Janki Medical College and Hospital in Samastipur, Bihar.[200]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ David R. Kinsley (19 July 1988). Hindu Goddesses Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. p. 78. ISBN 9780520908833.

Tulsidas refers Sita as World's Mother And Ram as Father

- ^ Krishnan Aravamudan (22 September 2014). Pure Gems of Ramayanam. PartridgeIndia. p. 213. ISBN 9781482837209.

Sage Narada Refers to Sita As Mystic Goddess of Beauty

- ^ Sally Kempton (13 July 2015). Awakening Shakti. Jaico Publishing House. ISBN 9788184956191.

Sita Goddess of Devotion

- ^ Tattwananda, Swami (1984). Vaisnava Sects, Saiva Sects, Mother Worship (1st revised ed.). Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Ltd.

- ^ "Rs 48.5 crore for Sita's birthplace". The Telegraph. India.

- ^ a b "Hot spring hot spot – Fair begins on Magh full moon's day". The Telegraph. India. Retrieved 22 December 2018.

- ^ a b "Sitamarhi". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ a b "History of Sitamarhi". Official site of Sitamarhi district. Archived from the original on 20 December 2014. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ^ "Janakpur". sacredsites.com.

- ^ "Nepal, India PMs likely to jointly inaugurate cross-border railway link". WION India. 24 March 2022.

- ^ "India-Nepal rail link: Janakpur to be major tourist attraction". The Print. 2 April 2022.

- ^ a b Moor, Edward (1810). The Hindu Pantheon. J. Johnson. p. 316.

- ^ Publishing, Bloomsbury (13 September 2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations [2 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 457. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ^ Sutherland, Sally J. "Sita and Draupadi, Aggressive Behavior and Female Role-Models in the Sanskrit Epics" (PDF). University of California, Berkeley. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 May 2013. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ a b c Swami Parmeshwaranand (1 January 2001). Encyclopaedic Dictionaries of Puranas. Sarup & Sons. pp. 1210–1220. ISBN 978-81-7625-226-3. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "The haughty Ravana". The Hindu. 10 April 2014. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 2 July 2020.

- ^ Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 78.

- ^ Yadav, Ramprasad (2016). "Historical and Cultural Analysis of Ramayana: An Overview". International Journal of Historical Studies. 8 (4): 189–204.

- ^ a b Suresh Chandra (1998). Encyclopaedia of Hindu Gods and Goddesses. Sarup & Sons. pp. 304–. ISBN 978-81-7625-039-9. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ^ Stephanie Jamison (2015). The Rigveda –– Earliest Religious Poetry of India. Oxford University Press. p. 643. ISBN 978-0190633394.

- ^ a b Heidi Rika Maria Pauwels (2007). Indian Literature and Popular Cinema: Recasting Classics. Routledge. pp. 53–. ISBN 978-0-415-44741-6. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Bihar times". Archived from the original on 19 October 2014.

- ^ "Modi's visit to Sita's birthplace in Nepal cancelled". The Times of India. 20 November 2014.

- ^ "Janakpur". Sacred Sites: World Pilgrimage Guide. Retrieved 8 June 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Singaravelu, S (1982). "Sītā's Birth and Parentage in the Rāma Story". Asian Folklore Studies. 41 (2). University of Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: 235–240. doi:10.2307/1178126. JSTOR 1178126.

- ^ "Sita's Sisters: Conversations on Sisterhood Between Women of Ramayana". Outlook. New Delhi. 23 October 2023. Retrieved 26 October 2023.

- ^ Mishra, V. (1979). Cultural Heritage of Mithila. Allahabad: Mithila Prakasana. p. 13. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ Praśānta Guptā (1998). Vālmīkī Rāmāyaṇa. Dreamland Publications. p. 32. ISBN 9788173012549.

- ^ Bhalla, Prem P. (1 January 2009). The Story of Sri Ram. Peacock Books. ISBN 978-81-248-0191-8.

- ^ Debroy, Bibek (2005). The History of Puranas. Bharatiya Kala Prakashan. ISBN 978-81-8090-062-4.

- ^ Valmiki. The Ramayana. pp. 126–145.

- ^ Harvard. "Ravana's Abduction of Sita, folio from a Ramayana Series". Harvard Art Museums. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ Ramanujan, A. K. (1 March 2023). Teen Sau Ramayan [Three Hundred Ramayanas]. Vani Prakashan. p. 80. ISBN 978-9350721728.

- ^ "The golden deer". The Hindu. 16 August 2012. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 22 April 2024.

- ^ a b Mani pp. 720–3; Mani, Vettam (1975). Puranic Encyclopaedia: a Comprehensive Dictionary with Special Reference to the Epic and Puranic Literature. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 978-0-8426-0822-0.

- ^ Pargiter, F. E. (2011). "The Geography of Ráma's Exile". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 2 (26): 231–264.

- ^ Robert P. Goldman; Sally Sutherland Goldman, eds. (1996), The Ramayana of Valmiki: An Epic of Ancient India : Sundarkand, Princeton University Press, pp. 80–82, ISBN 978-0-691-06662-2

- ^ SarDesai, D. R. (4 May 2018), "India in Prehistoric Times", India, Routledge, pp. 15–28, doi:10.4324/9780429499876-2, ISBN 978-0-429-49987-6, retrieved 21 April 2024

- ^ Ramashraya Sharma (1986). A Socio-political Study of the Vālmīki Rāmāyaṇa. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 2–3. ISBN 978-81-208-0078-6.

- ^ Gregory Claeys (2010). The Cambridge Companion to Utopian Literature. Cambridge University Press. pp. 240–241. ISBN 978-1-139-82842-0.

- ^ Cakrabartī, Bishṇupada (2006). The Penguin Companion to the Ramayana. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-310046-1. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 12 July 2022.

- ^ Bhargava, Anju P. "Contemporary Influence of Sita by". The Infinity Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 July 2012. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- ^ "Padma-puran pdf file" (PDF). 1 October 2018. Retrieved 1 October 2018.

- ^ "Uttara Kanda of Ramayana was edited during 5th century BCE – Puranas". BooksFact – Ancient Knowledge & Wisdom. 26 April 2020. Retrieved 7 July 2020.

- ^ MacFie, J. M. (1 May 2004). The Ramayan of Tulsidas or the Bible of Northern India. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-1498-2.

- ^ Valmiki, Ramayana. "Aranya Kanda in Prose Sarga 49". valmikiramayan.net.

- ^ Richman, Paula (1 January 2001). Questioning Ramayanas: A South Asian Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22074-4.

- ^ Valmiki, Ramayana. "Sundarkanda, sarga 37". valmiki.iitk.ac.in. IIT Kanpur.

- ^ Pai, Anant (1978). Valmiki's Ramayana. India: Amar Chitra Katha. pp. 1–96.

Sita

- ^ Ramcharitmanas – Balkand, Manglacharan

- ^ Tinoco 1996.

- ^ Prasoon 2008, p. 82.

- ^ Tinoco 1996, p. 88.

- ^ Mahadevan 1975, p. 239.

- ^ a b Dalal 2014, p. 1069.

- ^ Wilson, H. H. (1840). The Vishnu Purana: A system of Hindu mythology and tradition. Oriental Translation Fund.

- ^ Rocher, Ludo (1986). The Puranas. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447025225.

- ^ Kinsley, David (19 July 1988). Hindu Goddesses: Visions of the Divine Feminine in the Hindu Religious Tradition. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-90883-3.

- ^ Dalal, Roshen (14 July 2017), "Hinduism and its basic texts", Reading the Sacred Scriptures, New York: Routledge, pp. 157–170, doi:10.4324/9781315545936-11, ISBN 978-1-315-54593-6

- ^ Buitenen, J. A. B. van (1973). The Mahabharata, Volume 2: Book 2: The Book of Assembly; Book 3: The Book of the Forest. University of Chicago Press. pp. 207–214. ISBN 978-0-226-84664-4.

- ^ Valmiki (6 October 2023). Valmiki Samhita (वाल्मीकि संहिता).

- ^ Bhagavānadāsa, Vaishṇava (1992). Ramanand Darshan Samiksha (in Sanskrit and Hindi) (1st ed.). Prajñā Prakāśana Mañca. p. 12.

- ^ "Maithili Mahopanishat". sanskritdocuments.org. Retrieved 6 December 2023.

- ^ Maha Upaniṣad, Maithili (1934). Kalyan Shakti Anka (1st ed.). Gita Press Gorakhpur. p. 211.

- ^ "Goswāmi Tulasīdās". lordrama.co.in. Retrieved 20 May 2023.

- ^ "Stuti Vinay Patrika". Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ Varnekar, Dr. Sridhar Bhaskar (1988). Sanskrit Vadamay Kosh (in Hindi) (1st ed.). Kolkata: Bhartiye Bhasha Parishad. p. 430.

- ^ Pandey, Dr. Rajbali (1970). Hindu Dharma Kosha (5th ed.). Lucknow: Uttar Pradesh Hindi Sansthan. p. 612. ISBN 9788193783948.

- ^ M. R. Kale (ed, 1922), The Raghuvamsa of Kalidasa: with the commentary (the Samjivani) of Mallinatha; Cantos I-X

- ^ a b c Pauwels 2008, pp. 12–15, 497–517.

- ^ Vālmīki (1990). The Ramayana of Valmiki: Balakanda. Translated by Robert P Goldman. Princeton University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-4008-8455-1.

- ^ Marijke J. Klokke (2000). Narrative Sculpture and Literary Traditions in South and Southeast Asia. BRILL. pp. 51–57. ISBN 90-04-11865-9.

- ^ Dimock 1963, pp. 106–127.

- ^ Bhandarkar, R. G. (20 May 2019). Vaisnavism, Saivism and minor religious systems. De Gruyter. doi:10.1515/9783111551975. ISBN 978-3-11-155197-5.

- ^ "'जानकी रामायण', ऐसी रामायण जो राम पर नहीं सीता पर आधारित है" (in Hindi). News18 हिंदी. 7 November 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2024.

- ^ लालदास (1980). जानकी-रामायण: प्रबन्ध-काव्य (in Hindi). Maithilī Akādamī.

- ^ "Five other Ramayanas: Sita as Kali, Lakshman as Ravana's slayer and more". 6 May 2015. Retrieved 14 September 2019.

- ^ Grierson, Sir George (1926). "On the Adbhuta-Ramayana". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 4 (11–27): 11–27. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0010254X.

- ^ Mirashi, V. V. (1996). "The Mahavira-charita". Bhavabhūti. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. ISBN 81-208-1180-1.

- ^ Kandali, Madhava. সপ্চকাণ্ড ৰামায়ন [Saptakanda Ramayana] (in Assamese). Banalata.

- ^ a b Madhubani Painting. Abhinav Publications. 30 September 2017. ISBN 9788170171560. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017.

- ^ T. A. Gopinatha Rao (1993). Elements of Hindu iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 189–195. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2. Archived from the original on 11 November 2023. Retrieved 10 April 2017.

- ^ Mohan, Urmila (2018). "Clothing as devotion in Contemporary Hinduism". Brill Research Perspectives in Religion and Art. 2 (4): 1–82. doi:10.1163/24688878-12340006. S2CID 202530099.

- ^ a b c d Warrier 1967, pp. 85–95.

- ^ Hattangadi 2000.

- ^ "Valmiki Ramayana – Aranya Kanda in Prose Sarga 46". Valmiki's Ramayana.

- ^ R Gandhi (1992), Sita's Kitchen, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0791411537, page 113 with note 35

- ^ Deussen, Paul (1997). Sixty Upanishads of the Veda. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1467-7.

- ^ Shimkhada, D. and P.K. Herman (2009). The Constant and Changing Faces of the Goddess: Goddess Traditions of Asia. Cambridge Scholars, ISBN 978-1-4438-1134-7

- ^ "Jain Ramayana". en.encyclopediaofjainism.com. 21 September 2014. Archived from the original on 13 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ Iyengar, Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa (2005). Asian Variations in Ramayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- ^ "The Jataka, Vol. IV: No. 461.: Dasaratha-Jātaka". sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Dasaratha Jataka (#461)". The Jataka Tales. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Dhar, Aarttee Kaul. "Ramayana and Sita in Films and Popular Media:The Repositioning of a Globalised Version".

- ^ Arun, Rajendra (2000). Sita: The Divine Mother. Ocean Books. ISBN 9788187100492.

- ^ "Sitayanam…". sitayanam.com. Archived from the original on 1 January 2009.

- ^ Mukherjee, Prabhati (1999). Hindu Women: Normative Models. Calcutta: Orient Blackswan. ISBN 81-250-1699-6.

- ^ a b "Revisiting Sita of Shri Ram: The equal partner". India Today. 22 January 2024. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 12 February 2024.

- ^ "Contemporary Influence of Sita – Anju P. Bhargava". Infinity Foundation. Retrieved 19 January 2021.

- ^ "Here's what you can do when you are in Janakpur including Janaki Mandir".

- ^ "Ram temple fillip: Bihar acquires 50 acres in Sitamarhi for Sita temple". The Indian Express. 19 March 2024. Retrieved 19 March 2024.

- ^ "After Ayodhya's Ram Mandir, NDA govt will construct Sita Mata temple in Bihar's Sitamarhi". The Indian Express. 19 March 2024. Retrieved 27 May 2024.

- ^ "Sita Kund: Holy Site of Munger". Im:Bihar. Archived from the original on 3 March 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- ^ Ltd, Infokerala Communications Pvt (1 August 2015). Pilgrimage to Temple Heritage 2015. Info Kerala Communications Pvt Ltd. ISBN 978-81-929470-1-3.

- ^ "India sends holy Sarayu water to Sri Lanka for consecration ceremony of Seetha Amma temple". The Hindu. 28 April 2024. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Sinha, Amitabh (26 April 2023). "'Epic' Ties: Sri Lankan PM Unveils Special Cover for Sita Temple in Nuwara Eliya, Ramayana Trail to Be Made More Attractive". News18.

- ^ Tiptoeing on Sita trail in Wayanad(17 June 2018), Onmanorama

- ^ Singh, Kautilya (12 November 2019). "Uttarakhand set to come up with a massive Sita temple". The Times of India. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- ^ "Sita temple in Yavatmal: A unique shrine without the idol of Lord Rama". Lokmat Times. Retrieved 10 January 2024.

- ^ "सीतामढ़ी". Navbharat Times (in Hindi). Retrieved 11 May 2024.

- ^ "'Sita Ki Rasoi', The Sacred Temple Kitchen Where Goddess Sita Cooked". The Times of India. 10 March 2024. Retrieved 12 March 2024.

- ^ Raj, Selva J.; Harman, William P. (1 January 2006). Dealing with Deities: The Ritual Vow in South Asia. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-6708-4.

- ^ Larson, Gerald James (16 February 1995). India's Agony Over Religion: Confronting Diversity in Teacher Education. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2412-4. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ^ Lorenzen, David N. (1999). "Who Invented Hinduism?". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 41 (4): 630–659. doi:10.1017/S0010417599003084 (inactive 1 November 2024). ISBN 9788190227261. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 179424. S2CID 247327484. Archived from the original on 23 December 2023. Retrieved 6 March 2021 – via Book.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ Tattwananda, Swami (1984). Vaisnava Sects, Saiva Sects, Mother Worship (1st revised ed.). Calcutta: Firma KLM Private Ltd. p. 68.

- ^ Mahadevan 1975, pp. 239–240.

- ^ VR Rao (1987), Selected Doctrines from Indian Philosophy, South Asia Books, ISBN 978-8170990000, page 21

- ^ Johnsen 2002, p. 55.

- ^ Nair 2008, p. 581.

- ^ "6.1 Many Ramayanas: text and tradition – The Ramayan". Coursera. Retrieved 15 August 2020.

- ^ Nagar, Shantilal (2006). Ananda Ramayana. Delhi, India: Parimal Publications. p. 946. ISBN 81-7110-282-4.

- ^ "Vinay Patrika website, Kashi Hindu Vishwavidhyalaya". Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 25 October 2007.

- ^ "Tulsidas's Janaki Mangal". Archived from the original on 28 November 2006. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ "Sita Navami 2024: Plant Parijat for happiness and prosperity". The Times of India. 30 April 2024. ISSN 0971-8257. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Sita Navami 2023: Date, history, significance and all you need to know". The Economic Times. 28 April 2023. ISSN 0013-0389. Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Sita Navami 2024: Date, history, rituals, significance, celebration and all that you need to know". Hindustan Times. 15 May 2024. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Sita Navami 2024 : सीता नवमी कब है? नोट कर लें डेट, पूजा- विधि, शुभ मुहूर्त और महत्व". Hindustan (in Hindi). Retrieved 5 May 2024.

- ^ "Vivah Panchami 2023: Date, Time, Significance And All You Need To Know". ABP Live. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ "2015 Vivah Panchami". DrikPanchang. Retrieved 20 February 2015.

- ^ "धूमधाम से मनाया जा रहा विवाह पंचमी त्योहार:आज ही हुआ था भगवान राम और देवी सीता का विवाह". Dainik Bhaskar. 17 December 2023. Retrieved 26 December 2023.

- ^ Gupta, Shakti M. (1991). Festivals, Fairs, and Fasts of India. University of Indiana, United States: Clarion Books. ISBN 9-788-185-12023-2. OCLC 1108734495.

- ^ Encyclopedia Britannica 2015.

- ^ Kasbekar, Asha (2006). Pop Culture India!: Media, Arts, and Lifestyle. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-636-7. Archived from the original on 31 January 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2021.

- ^ "Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage". Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 5 September 2009.

- ^ Bose, Mandakranta (2004). The Ramayana Revisited. Oxford University Press. pp. 342–350. ISBN 978-0-19-516832-7.

- ^ Muskan Singh. "Playing Sita in Ramleela: One Role, Many Actors, Same Belief". The Quint. Retrieved 28 November 2023.

- ^ Om Lata Bahadur (2006). John Stratton Hawley; Vasudha Narayanan (eds.). The Life of Hinduism. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-24914-1.

- ^ N, Ramesan (1981). The Tirumala Temple. Tirupati: TTD.

- ^ "Vasanthotsavam begins". The Hindu. 12 April 2006. Archived from the original on 19 April 2006. Retrieved 18 April 2008.

- ^ The Episodes of Ramayana Stories (Indonesian version)

- ^ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella (ed.). The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans. Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- ^ Nurdin. J aka J. Noorduyn: 1971.Traces of an Old Sundanese Ramayana Tradition in Indonesia, Vol. 12, (Oct. 1971), pp. 151–157 Southeast Asia Publications at Cornell University. Cornell University: 1971

- ^ Soedjono (1978), Lahirnya Dewi Sinta, Tribisana Karya

- ^ Hooykaas C. The Old Javanese Ramayana Kakawin. The Hague: Nijhoff: 1955.

- ^ "Ramayana(s) retold in Asia". The Hindu. 19 February 2012. Retrieved 7 February 2015.

- ^ Robson, Stuart. Old Javanese Ramayana. Tokyo: Tokyo University of Foreign Studies, 2015.

- ^ "Wayang Indonesia". Archived from the original on 9 October 2009. Retrieved 13 December 2009.

- ^ Dewi Shinta : Sifat dan Kisah Cerita, 15 July 2018

- ^ Tambora boyak, Dewi Shinta, Sebuah Gambaran Keteguhan Seorang Feminis

- ^ Reamker Epic Legend – a forum post

- ^ Marrison, G. E. (January 1989). "Reamker (Rāmakerti), the Cambodian version of the Rāmāyaṇa.* a review article". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 121 (1): 122–129. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00167917. ISSN 2051-2066. S2CID 161831703.

- ^ "National Heroes / Personalities / Luminaries of Nepal". ImNepal.com. 23 December 2011. Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ^ John Cadet, The Ramakien, illustrated with the bas-reliefs of Wat Phra Jetubon, Bangkok, ISBN 9-7489-3485-3

- ^ Ding, Emily (1 August 2016). "A New Hope". Roads and Kingdoms. Retrieved 13 March 2017.

- ^ Characters of the Phra Lak Phra Lam Archived 2021-10-24 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ James G. Lochtefeld 2002.

- ^ "Rājput painting". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 20 March 2023.

- ^ "Sāhibdīn". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ Edward O. Henry (1998). "Maithil Women's Song: Distinctive and Endangered Species". Ethnomusicology. 42 (3): 415–440. doi:10.2307/852849. JSTOR 852849.

- ^ "Maithili Music of India and Nepal : SAARC Secreteriat". SAARC Music Department. South Asian Association For Regional Cooperation. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Richman 1991, p. 17.

- ^ Norvin Hein (1958). "The Ram Lila". Journal of American Folklore. 71 (281): 279–304. doi:10.2307/538562. JSTOR 538562.

- ^ Frazier, Donald (11 February 2016). "On Java, a Creative Explosion in an Ancient City". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 April 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2017.

- ^ Willem Frederik Stutterheim (1989). Rāma-legends and Rāma-reliefs in Indonesia. Abhinav Publications. pp. 109–160. ISBN 978-81-7017-251-2.

- ^ James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture: Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature, and Art (Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press, 1988), p. 223. Cited in Yamashita (1999), p.178.

- ^ "All About Devi Sita". 17 May 2021.

- ^ Breman 1999, p. 270.

- ^ a b Onial, Devyani (6 August 2020). "From assertive 'Jai Shri Ram', a reason to move to gentler 'Jai Siya Ram'". The Indian Express. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 6 August 2020.

- ^ Wilson, H. H. (1958) [1861], Religious sects of the Hindus (Second ed.), Calcutta: Susil Gupta (India) Private Ltd. – via Internet Archive

- ^ MOLESWORTH, James T. (1857). A Dictionary English and Maráthí ... commenced by J. T. Molesworth ... completed by T. Candy.

- ^ "Chants of 'Jai Shree Ram' fill air as sadhus march for holy dip". The Indian Express. 30 August 2015. Retrieved 13 August 2020.

- ^ Balajiwale, Vaishali (14 September 2015). "More than 25 lakh devotees take second Shahi Snan at Nashik Kumbh Mela". Daily News and Analysis. Retrieved 14 August 2020.

- ^ Breman 1999.

- ^ "This is Sita's story, where Ram is just a character: Amish Tripathi". Hindustan Times. 19 May 2017. Retrieved 21 November 2019.

- ^ Mankekar, Purnima (1999). Screening Culture, Viewing Politics: An Ethnography of Television, Womanhood, and Nation in Postcolonial India. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-2390-7.

- ^ Vijayakumar, B. (3 August 2014). "Films and the Ramayana". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ^ Bhagwan Das Garg (1996). So many cinemas: the motion picture in India. Eminence Designs. p. 86. ISBN 81-900602-1-X.

- ^ "Ramayanam Reviews". Archived from the original on 13 February 1998.

- ^ "Lav Kush (1997)". Bollywood Hungama. Archived from the original on 4 September 2012. Retrieved 21 February 2020.

- ^ Nagpaul D'souza, Dipti (17 September 2010). "Epic Effort". The Indian Express. Retrieved 18 September 2010.

- ^ "Telugu Review: 'Sri Rama Rajyam' is a must watch". CNN-IBN. Archived from the original on 22 November 2011. Retrieved 20 November 2011.

- ^ "Kriti Sanon wraps Adipurush, says Janaki's 'loving heart, pious soul and unshakable strength will stay' within her forever". The Indian Express. 16 October 2021. Archived from the original on 16 October 2021. Retrieved 16 October 2021.

- ^ Dalrymple, William (23 August 2008). "All Indian life is here". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 2 September 2013. Retrieved 15 February 2018.

- ^ "Sita Sings the Blues reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 21 June 2020. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ^ Bhattacharyya, Anushree (27 August 2013). "An epic battle". The Financial Express. India. Archived from the original on 9 January 2021. Retrieved 30 May 2020.

- ^ "I've gained a new perspective on Sita: Madirakshi Mundle". Deccan Chronicle. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- ^ "Ram Siya Ke Luv Kush". PINKVILLA. Archived from the original on 3 December 2020. Retrieved 5 August 2019.

- ^ "Ramyug first impression: Kunal Kohli's retelling of Lord Ram's story misses the mark". The Indian Express. 6 May 2021. Retrieved 31 July 2023.

- ^ "Shrimad Ramayan Promo: Prachi Bansal introduced as Sita in the new Sony Entertainment Television show". Bollywood Hungama. 8 December 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2023.

- ^ Shanta Gokhale. "What about Urmila?". Mumbai Mirror. Retrieved 17 December 2021.

- ^ "Darpan theatre festival: Tales of epic love, sacrifice draw applause". Hindustan Times. 19 May 2023. Retrieved 19 September 2023.

- ^ Gokhale, Namita (15 October 2009). In Search of Sita: Revisiting Mythology. Penguin Books Limited. ISBN 9789354922305.

- ^ Arni, Samhita; Chitrakar, Moyna (2011). Sita's Ramayana. Groundwood Books. ISBN 9781554981458.

- ^ Pattanaik, Devdutt (20 October 2013). Sita: A Tale of Ancient Love. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. ISBN 9789351184201.

- ^ Iyengar, Aditya (25 July 2019). Bhumika: A Story of Sita. Hachette India. ISBN 9789388322362.

- ^ Banerjee Divakaruni, Chitra (7 January 2019). The Forest of Enchantments. HarperCollins Publishers India. ISBN 9789353025991.

- ^ Narasimhan, Bhanumathi (15 October 2021). Sita: A Tale of Ancient Love. Penguin Random House India Private Limited. ISBN 9789354922305.

- ^ Tripathi, Amish (25 July 2022). Sita: Warrior of Mithila. HarperCollins India. ISBN 9789356290945.

- ^ Bhelari, Amit (21 January 2024). "Nitish dedicates 500-bed hospital named after Lord Ram and goddess Sita". The Hindu. Retrieved 28 January 2024.

Sources

- Dimock, Jr, E.C. (1963). "Doctrine and Practice among the Vaisnavas of Bengal". History of Religions. 3 (1): 106–127. doi:10.1086/462474. JSTOR 1062079. S2CID 162027021.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Prasoon, Prof.S.K. (1 January 2008). Indian Scriptures. Pustak Mahal. ISBN 978-81-223-1007-8.

- Tinoco, Carlos Alberto (1996). Upanishads. IBRASA. ISBN 978-85-348-0040-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link) - Mahadevan, T. M. P. (1975). Upaniṣads: Selections from 108 Upaniṣads. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1611-4.

- Lochtefeld, James G. (2002). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism: N-Z. The Rosen Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-8239-3180-4.

Béteille, André; Guha, Ramachandra; Parry, Jonathan P., eds. (1999). Institutions and Inequalities: Essays in Honour of André Béteille. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-565081-6. OCLC 43419618.

- Breman, Jan. "Ghettoization and Communal Politics: The Dynamics of Inclusion and Exclusion in the Hindutva Landscape". In Béteille, Guha & Parry (1999).

- Richman, Paula (1991). Many Rāmāyaṇas: The Diversity of a Narrative Tradition in South Asia. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07589-4.

- Warrier, AG Krishna (1967). Śākta Upaniṣads. Adyar Library and Research Center. ISBN 978-0835673181. OCLC 2606086.

- Hattangadi, Sunder (2000). "सीतोपनिषत् (Sita Upanishad)" (PDF) (in Sanskrit). Retrieved 28 January 2016.

- Johnsen, Linda (2002). The Living Goddess. YI Publishers. ISBN 978-0936663289.

- Dalal, Roshen (2014). Hinduism: An Alphabetical Guide. Penguin. ISBN 978-81-8475-277-9.

- Nair, Shantha N. (1 January 2008). Echoes of Ancient Indian Wisdom. Pustak Mahal. ISBN 978-81-223-1020-7.

Further reading

- Jain, Pannalal (2000). Hiralal Jain, A.N. Upadhaye (ed.). Ravishenacharya's Padmapurana (in Hindi) (8th ed.). New Delhi: Bhartiya Jnanpith. ISBN 978-81-263-0508-7.

- Iyengar, Kodaganallur Ramaswami Srinivasa (2005). Asian Variations in Ramayana. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1809-3.

- Das, Sisir Kumar (2005). A History of Indian Literature, 500-1399: From the Courtly to the Popular. Sahitya Akademi. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0.

External links

Media related to Sita at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Sita at Wikimedia Commons Quotations related to Sita at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Sita at Wikiquote- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.