India ink

India ink (British English: Indian ink;[1] also Chinese ink) is a simple black or coloured ink once widely used for writing and printing and now more commonly used for drawing and outlining, especially when inking comic books and comic strips. India ink is also used in medical applications.

Compared to other inks, such as the iron gall ink previously common in Europe, India ink is noted for its deep, rich black color. It is commonly applied with a brush (such as an ink brush) or a dip pen (made out of bamboo or steel). In East Asian traditions such as ink wash painting and Chinese calligraphy, India ink is commonly used in a solid form called an inkstick.

Composition

[edit]Basic India ink is composed of a variety of fine soot, known as lampblack, combined with water to form a liquid. No binder material is necessary: the carbon molecules are in colloidal suspension and form a waterproof layer after drying. A binding agent such as gelatin or, more commonly, shellac may be added to make the ink more durable once dried. India ink is commonly sold in bottled form, as well as a solid form as an inkstick (most commonly, a stick), which must be ground and mixed with water before use. If a binder is used, India ink may be waterproof or non-waterproof.

History

[edit]

Woods and Woods (2000) state that the process of making India ink was known in China as early as the middle of the 3rd millennium BC, in Neolithic China,[2] whereas Needham (1985) states that inkmaking commenced perhaps as early as 3 millennia ago in China.[3] India ink was first invented in China,[4][5][6] but the English term India(n) ink was coined due to their later trade with India.[4][5] A considerable number of oracle bones of the late Shang dynasty contain incised characters with black pigment from a carbonaceous material identified as ink.[7] Numerous documents written in ink on precious stones as well as bamboo or wooden tablets dating to the Spring and Autumn, Warring States, and Qin period have been uncovered.[7] A cylindrical artifact made from black ink has been found in Qin tombs, dating back to the 3rd century BC during the Warring States or dynastic period, from Yunmeng, Hubei.[7]

India ink has been in use in India since at least the 4th century BC, where it was called masi, an admixture of several substances.[8] Indian documents written in Kharosthi with this ink have been unearthed in as far as Xinjiang, China.[9] The practice of writing with ink and a sharp-pointed needle in Tamil and other Dravidian languages was common practice from antiquity in South India, and so several ancient Buddhist and Jain scripts in India were compiled in ink.[10][11] In India, the carbon black from which India ink is formulated was obtained indigenously by burning bones, tar, pitch, and other substances.[12]

The traditional Chinese method of making ink was to grind a mixture of hide glue, carbon black, lampblack, and bone black pigment with a mortar and pestle, then pour it into a ceramic dish where it could dry.[4] To use the dry mixture, a wet brush would be applied until it rehydrated,[4] or more commonly in East Asian calligraphy, a dry solid ink stick was rubbed against an inkstone with water. Like Chinese black inks, the black inks of the Greeks and Romans were also stored in solid form before being ground and mixed with water for usage.[13] In contrast to Chinese inks that were permanent, these inks could be washed away with water.[13]

Pine soot was traditionally favored in Chinese inkmaking.[14] Several studies observed that 14th-century Chinese inks are made from very small and uniform pine soot; in fact the inks are even superior in these aspects to modern soot inks.[14] The author Song Yingxing (c. 1600–1660) of the Ming dynasty has described the inkmaking process from pine soot in his work Tiangong Kaiwu.[14] From the Song dynasty onwards, lampblack also became a favored pigment for the manufacturing of black inks.[14] It was made by combustion in lamps with wicks, using animal, vegetable, and mineral oils.[14]

In the Chinese record Tiangong Kaiwu, ink of the period was said to be made from lampblack of which a tenth was made from burning tung oil, vegetable oils, or lard, and nine-tenths was made from burning pine wood.[15] For the first process, more than one ounce (approx. 30 grams) lampblack of fine quality could be produced from a catty (approx. 0.5 kg) of oil.[15][14] The lampwick used in the making of lampblack was first soaked in the juice of Lithospermum officinale before burning.[15] A skillful artisan could tend to 200 lamps at once.[15] For the second process, the ink was derived from pine wood from which the resin had been removed.[15][14] The pine wood was burnt in a rounded chamber made from bamboo with the chamber surfaces and joints pasted with paper and matting in which there were holes for smoke emission.[15][14] The ground was made from bricks and mud with channels for smoke built in.[15][14] After a burn of several days, the resulting pine soot was scraped from the chamber after cooling.[15][14] The last one or two sections delivered soot of the purest quality for the best inks, the middle section delivered mixed-quality soot for ordinary ink, and the first one or two sections delivered low-grade soot.[15][14] The low-grade soot was further pounded and ground for printing, while the coarser grade was used for black paint.[15][14] The pine soot was soaked in water to divide the fine particles that float and the coarser particles that sink.[15] The sized lampblack was then mixed with glue after which the final product was hammered.[15] Precious components such as gold dust or musk essence may be added to either types of inks.[15]

In 1738, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde described the Chinese manufacturing process for lampblack from oil as: "They put five or six lighted wicks into a vessel full of oil, and lay upon this vessel an iron cover, made in the shape of a funnel, which must be set at a certain distance so as to receive all the smoke. When it has received enough, they take it off, and with a goose feather gently brush the bottom, letting the soot fall upon a dry sheet of strong paper. It is this that makes their fine and shining ink. The best oil also gives a lustre to the black, and by consequence makes the ink more esteemed and dearer. The lampblack which is not fetched off with the feather, and which sticks very fast to the cover, is coarser, and they use it to make an ordinary sort of ink, after they have scraped it off into a dish."[16]

The Chinese had used India ink derived from pine soot prior to the 11th century AD, when the polymath official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) of the mid Song dynasty became troubled by deforestation (due to the demands of charcoal for the iron industry) and sought to make ink from a source other than pine soot. He believed that petroleum (which the Chinese called 'rock oil') was produced inexhaustibly within the earth and so decided to make an ink from the soot of burning petroleum, which the later pharmacologist Li Shizhen (1518–1593) wrote was as lustrous as lacquer and was superior to pine soot ink.[17][18][19][20]

A common ingredient in India ink, called carbon black, has been used by many ancient historical cultures. For example, the ancient Egyptians and Greeks both had their own recipes for "carbon black". One Greek recipe, from 40 to 90 AD, was written, documented and still exists today.[21]

The ink from China was often sought after in the rest of the world, including Europe, due to its quality.[22] For instance, in the 17th century, Louis LeComte said of Chinese ink that "it is most excellent; and they have hitherto vainly tried in France to imitate it."[22] In another instance, in 1735, Jean-Baptiste Du Halde wrote that "the Europeans have endeavored to counterfeit this ink, but without success."[22] These qualities were described by Berthold Laufer: "It produces, first of all, a deep and true black; and second, it is permanent, unchangeable in color, and almost indestructible. Chinese written documents may be soaked in water for several weeks without washing out... In documents written as far back as the Han dynasty... the ink is as bright and well preserved as though it had been applied but yesterday. The same holds good of the productions of the printer's art. Books of the Yuan, Ming, and Ch'ing dynasties have come down to us with paper and type in a perfect state of composition."[22]

Artistic uses

[edit]- India ink is used in many common artist pens, such as Pitt Artist pens.

- Many artists who use watercolor paint or other liquid mediums use waterproof India ink for their outlining because the ink does not bleed once it is dry.

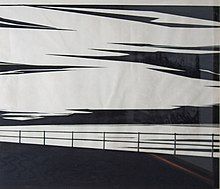

- Some other artists use both black and colored India ink as their choice medium in place of watercolors. The ink is diluted with water to create a wash, and typically done so in a ceramic bowl. The ink is layered like watercolors, but once dry, the ink is waterproof and cannot be blended.

- Ink blotting is a form of art in which the artist places a blob of ink on special paper. Using a blower (a hair dryer will also work), the artist blows the ink around the page, then, if desired, will fold the paper in half to get a mirror-image ink blot on either side of the page, creating a symmetrical image.

- Some artists who favor using monochromatic color palettes (one color but in different shades), especially grey tones, often use India ink for its ability to be mixed in water for lighter colors as well as its ability to layer colors without bleeding.

- Tattoo artists use India ink as a black ink for tattoos.[23]

Non-art use

[edit]

- In pathology laboratories, India ink is applied to surgically removed tissue specimens to maintain orientation and indicate tumor resection margins. The painted tissue is sprayed with acetic acid, which acts as a mordant, "fixing" the ink so it does not track. This ink is used because it survives tissue processing, during which tissue samples are bathed in alcohol and xylene and then embedded in paraffin wax. When viewed under the microscope, the ink at the tissue edge informs the pathologist of the surgical resection margin or other point of interest.

- Microbiologists use India ink to stain a slide containing micro-organisms. The background is stained while the organisms remain clear. This is called a negative stain. India ink, along with other stains, can be used to determine if a cell has a gelatinous capsule.[24] A common application of this procedure in the clinical microbiology laboratory is to confirm the morphology of the encapsulated yeast Cryptococcus spp. which cause cryptococcal meningitis.

- In microscopy, India Ink is used to circle mounted specimens like diatoms or radiolarians for better finding them on the slide.

- Medical researchers use India ink to visualize blood vessels when viewed under a microscope.

- When assaying phagocytosis scientists often use India ink because it is easy to see and easy for cells to take up.[25]

- Scientists performing Western blotting may use India ink to visualize proteins separated by electrophoresis and transferred to a nitrocellulose or PVDF membrane.

- In ophthalmology, it was and still is used to some extent in corneal tattooing.

- Once dry, its conductive properties make it useful for electrical connections on difficult substrates, such as glass. Although relatively low in conductivity, surfaces can be made suitable for electroplating, low-frequency shielding, or for creating large conductive geometries for high voltage apparatuses. A piece of paper impregnated with India ink serves as a grid leak resistor in some tube radio circuits.

- In 2002, NASA patented a process for polishing aluminium mirror surfaces to optical quality, using India ink as the polishing medium.[26][27]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ "Oxford English Dictionary". www.oed.com/. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 25 August 2017.

- ^ Woods & Woods, 51–52.

- ^ Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 233.

- ^ a b c d Gottsegen, page 30.

- ^ a b Smith, page 23.

- ^ Avery, page 138.

- ^ a b c Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 238.

- ^ Banerji, page 673

- ^ Sircar, page 206

- ^ Sircar, page 62

- ^ Sircar, page 67

- ^ "India ink" in Encyclopædia Britannica. 2008 Encyclopædia Britannica Inc.

- ^ a b Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 236.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 240-241.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Sung, Sun & Sun, pages 285–287.

- ^ Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 241-242.

- ^ Sivin, III, page 24.

- ^ Menzies, page 24.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, pages 75–76.

- ^ Deng, page 36.

- ^ "Spotlight on Indian Ink". Winsor & Newton. 10 November 2013.

- ^ a b c d Needham (1985). Volume 5, part 1, page 237.

- ^ "Spotlight on Indian Ink". www.winsornewton.com. Retrieved 20 August 2017.

- ^ Woeste and Demchick, Volume 57, Part 6, pages 1858–1859

- ^ Koszewski, B.J . (1957). "tudies of Phagocytic Activity of Lymphocytes : III. Phagocytosis of Intravenous India Ink in Human Subjects". Blood. 12 (6): 559–566. doi:10.1182/blood.v12.6.559.559. PMID 13436512.

- ^ NASA Technical Brief

- ^ US 6350176, "High Quality Optically Polished Aluminum Mirror and Process for Producing", published 2002-02-26

Publications

[edit]- Avery, John Scales (2012). Information Theory and Evolution (2nd ed.). Singapore: World Scientific. p. 138. ISBN 9789814401241.

- Banerji, Sures Chandra (1989). A Companion to Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0063-X.

- Deng, Yinke (2005). Ancient Chinese Inventions. Translated by Wang Pingxing. Beijing: China Intercontinental Press. ISBN 7-5085-0837-8.

- Gottsegen, Mark D. (2006). The Painter's Handbook: A Complete Reference. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-3496-8.

- Menzies, Nicholas K. (1994). Forest and Land Management in Imperial China. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 0-312-10254-2.

- Needham, Joseph (1985). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 1, Paper and Printing. Cambridge University Press.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology; the Gunpowder Epic. Taipei: Caves Books, Ltd.

- Sircar, D.C. (1996). Indian epigraphy. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1166-6.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: Variorum, Ashgate Publishing.

- Smith, Joseph A. (1992). The Pen and Ink Book: Materials and Techniques for Today's Artist. New York: Watson-Guptill Publications. ISBN 0-8230-3986-2.

- Sung, Ying-hsing; Sun, E-tu Zen; Sun, Shiou-chuan (1997). Chinese Technology in the Seventeenth Century: T'ien-kung K'ai-wu. Mineola: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-29593-1.

- Woods, Michael; Woods, Mary (2000). Ancient Communication: Form Grunts to Graffiti. Minneapolis: Runestone Press; an imprint of Lerner Publishing Group.....

- Woeste S.; Demchick, P. (1991). Appl Environ Microbiol. 57(6): 1858–1859 ASM.org

- History of Tattoos, The Tattoo Collection, No Date Published Archived 3 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine

External links

[edit]- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.