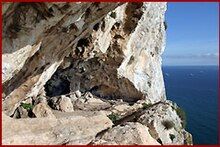

Martin's Cave

| Martin's Cave | |

|---|---|

Inside Martin's Cave | |

| Location | Eastern face of the Rock of Gibraltar, Gibraltar |

| Coordinates | 36°07′23.7″N 5°20′29.2″W / 36.123250°N 5.341444°W |

| Geology | Limestone |

| Entrances | 1 |

| Access | Mediterranean Steps |

Martin's Cave is a cave in the British Overseas Territory of Gibraltar. It opens on the eastern cliffs of the Rock of Gibraltar, below its summit at O'Hara's Battery. It is an ancient sea cave, though it is now located over 700 feet (210 m) above the shore of the Mediterranean Sea. It is only accessible because Martin's Path was constructed.

Geography

[edit]Gibraltar is sometimes referred to as the "Hill of Caves" and the geological formation of all the caves is limestone. Formed before the arrival of humans, its creation, and that of other caves in its vicinity, is attributed to the cracks and fissures within formations of the rock along which erosion occurred. Its extreme length from the entrance is 114 feet (35 m), while its greatest breadth is 73.16 feet (22.30 m). There is only one outlet from within the cave.[1]

History

[edit]

The cave was said to have been discovered in 1821 by a soldier named Martin, after whom it was named.[1] According to an 1829 account, the soldier had been "wandering about the summit of the Rock somewhat inebriated" and was absent from that evening's muster. He was feared to have fallen over the precipice and to have been dashed to pieces on the rocks below. Three days after disappearing, however, he reappeared with torn and dirty clothes and a haggard appearance. He had indeed fallen but had landed on a narrow ledge in front of the entrance to the cave, before being rescued.[2] At the time, reaching the cave was very difficult. The Royal Engineers built Martin's Path, a small approach path above the precipice to facilitate access.[1] A visitor described the perilous journey to get there a few years after it was discovered:

The path which we are obliged to traverse in order to get to it, is one of considerable difficulty and danger. We left our horses in charge of a servant half a mile from the cave, and proceeded along a narrow ledge, formed by art and with much labor, about three feet wide, until we reached the desired spot ... The south end and all the eastern side of Gibraltar is – or rather had been deemed, inaccessible, as it rises perpendicularly from the sea, and presents to the eye no ledges or asperities to encourage one to ascend or descent it, no matter what might be his inducement.[2]

In the 1860s, Captain Frederick Brome, the governor of Gibraltar's military prison, sought permission from the Governor of Gibraltar to explore Martin's Cave, as well as St. Michael's Cave, Fig Tree Cave and Poca Roca Cave, with the objective of finding archaeological evidence of the past use of the caves. The Governor readily agreed to the proposal. A ten-member team of prisoners began the explorations, with Martin's Cave being the first to be explored.[1] Excavations commenced on 23 June 1868, and continued until 22 July. There were no discernible traces of any previous attempts at detailed exploration, and no inscription earlier than 1822 could be discovered in the cave.[1] Parts of a human lower jaw, and two bushels of bones belonging to ox, goat, sheep, and rabbit were found; there were also several bird and fish bones. Other finds included two bushels of broken pottery, of which 57 pieces were ornamented; 61 handles and pots; 6 stone axes and 70 flint knives; a portion of an armlet and anklet; and 10 pounds of sea shells.[3] A small, brightly coloured, enamelled copper plate was also found, which appears to have had a design upon it of a bird with an open bill in the coils of a serpent. Similar works of art, consisting of fragments of pottery, flint and stone implements were unearthed.[3] The two swords both just over a metre long dating to the 12th or 13th century were also unearthed.[4][5] The British Museum has seven items in its collection donated by Captain Brome. Six of these are the two swords, a scabbard, two buckles and a plaque which were all originally found in Martin's Cave.[6]

During World War II Gibraltar's caves were extended and exploited by the military, and Martin's Cave was used to house electric generators. The generators were removed but the holes that were drilled in the roof of the cave still have cables as evidence of the caves industrial use.[7] A nearby battery also became known as Martin's Battery.

The cave is briefly lit by natural light just after sunrise. Due to past vandalism, the entrance to the cave is kept behind a padlocked gate which is a branch off the nature trail called Mediterranean Steps.[7]

Bats

[edit]The cave has been home to large groups of bats in the past. In November 1966, the cave was surveyed by the Gibraltar Cave Research Group; a painted sign on the cave's wall mentions this.[4] An estimated 5000 Schreibers' bats Miniopterus schreibersii and 1000 large mouse-eared bats Myotis myotis were there in the '60s. There were no bats found in a 2002 survey of the cave, with incidents of fireworks usage within the cave reported as contributing to the matter.[8]

Protection

[edit]This cave was included in the caves listed in the Heritage and Antiquities Act 2018 by the Government of Gibraltar, noting that its archaeology was Palaeolithic, Neolithic and Medieval.[9]

References

[edit] This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: British Association for the Advancement of Science report (1868)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: British Association for the Advancement of Science report (1868)

- ^ a b c d e International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology (1869). Transactions of the third session which opened at Norwich on the 20th August and closed in London on the 28th August 1868. London: Longmans, Green, and co. pp. 113, 134–136. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Sketch: St Martin's Cave". The Critic: A Weekly Review of Literature, Fine Arts, and the Drama, Volume 1. New York: Critic Press. 21 February 1829. p. 272.

- ^ a b "Report on recent explorations in the Gibraltar caves, by Capt. Fred. Brome". Report of the Thirty-Seventh Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. British Association for the Advancement of Science. 1868. p. 56. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

- ^ a b "Exciting Caves". Gibraltar Information. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ Nicolle, David (25 January 2001). The Moors: The Islamic West 7th-15th Centuries AD. Osprey Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-85532-964-5. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ^ "Collection database search". British Museum. Retrieved 11 May 2013.

- ^ a b Crone, Jim. "Martin's Cave". DiscoverGibraltar.com. Archived from the original on 5 September 2013. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Perez, Charles E. Upper Rock Nature Reserve Management Action Plan (PDF). Gibraltar Ornithological & Natural History Society.

- ^ "Heritage and Antiquities Act 2018" (PDF). Gibraltar Gov Records. 2018 – via Government of Gibraltar.