Merzifon

Merzifon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 40°52′30″N 35°27′48″E / 40.87500°N 35.46333°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Amasya |

| District | Merzifon |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Alp Kargı (CHP) |

| Elevation | 750 m (2,460 ft) |

| Population (2021)[1] | 61,376 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 05300 |

| Website | merzifon |

Merzifon (Armenian: Մարզուան, romanized: Marzvan; Middle Persian: Merzban; Ancient Greek: Μερσυφὼν, romanized: Mersyphòn or Μερζιφούντα, Merzifounta) is a town in Amasya Province in the central Black Sea region of Turkey. It is the seat of Merzifon District.[2] Its population is 61,376 (2021).[1] The mayor is Alp Kargı (CHP).

Modern Merzifon is a typical large but quiet Anatolian town with schools, hospitals, courts and other important infrastructure but few cultural amenities. There is a large airbase nearby.

Merzifon is twinned with the city of Pleasant Hill, California.

Etymology

[edit]Former variants of its name include Marzifūn, Mersivan, Marsovan, Marsiwān, Mersuvan, Merzpond and Merzban. The name apparently comes from marzbān, the Persian title for a "march lord" or a district governor, although the exact connection is not clear. Scholar Özhan Öztürk, however, claims that original name was Marsıvan (Persian marz 'border + Armenian van 'town') which means "border town".[3]

Geography

[edit]Standing on a plain, watered by a river, Merzifon is on the road between the capital city of Ankara and Samsun on the Black Sea coast, 109 km from Samsun, 325 km from Ankara and 40 km west of the city of Amasya.

Climate

[edit]Merzifon has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csb). The weather is moderately cold in winter and warm in summer.

| Climate data for Merzifon (1991–2020) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 5.3 (41.5) |

7.7 (45.9) |

12.2 (54.0) |

17.6 (63.7) |

22.2 (72.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.1 (84.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

7.0 (44.6) |

17.8 (64.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.2 (34.2) |

2.6 (36.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

11.1 (52.0) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

18.2 (64.8) |

13.6 (56.5) |

7.1 (44.8) |

2.9 (37.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −2.0 (28.4) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

1.7 (35.1) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.2 (55.8) |

15.5 (59.9) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.3 (54.1) |

8.4 (47.1) |

2.8 (37.0) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

6.8 (44.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 38.34 (1.51) |

27.17 (1.07) |

41.28 (1.63) |

51.02 (2.01) |

60.22 (2.37) |

54.75 (2.16) |

16.51 (0.65) |

15.47 (0.61) |

23.28 (0.92) |

30.76 (1.21) |

32.86 (1.29) |

43.85 (1.73) |

435.51 (17.15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6.7 | 5.4 | 7.4 | 8.2 | 9.2 | 8.2 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 3.3 | 5.2 | 5.6 | 6.8 | 72.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.8 | 70.3 | 65.8 | 61.9 | 63.1 | 63.9 | 60.4 | 60.9 | 62.3 | 66.1 | 70.0 | 75.5 | 66.2 |

| Source: NOAA[4] | |||||||||||||

History

[edit]Pre-Roman history

[edit]Archaeological evidence (hundreds of burial mounds or höyüks) indicates settlement of this well-watered area since the Stone Age (at least 5500 BC). The first fortifications were built by the Hittites, who were expelled in around 1200 BC by invaders descending from the Black Sea. After 700 BC the fortifications were rebuilt by the Phrygians, who left a number of burial mounds and other remains. From 600 BC the Phrygians were pushed out by further invasions from the east, this time by Cimmerians from across the Caucasus mountains; graves from this period have been excavated and their contents displayed in the museum in Amasya. Merzifon then became a trading post of the kings of Pontus, who ruled the Black Sea coast from their capital in Amasya.

Rome and Byzantium

[edit]The district of Amasya was destroyed during civil wars of the Roman era but Merzifon was restored by command of the emperor Hadrian. Finds from Roman temples in Merzifon are also on display in the Amasya museum. The city grew in importance under Roman rule as its walls and fortifications were strengthened, and it remained strong under Byzantine rule (following the division of the Roman empire in 395), although it was held briefly by Arab armies during the 8th-century expansion of Islam. After this the castle of Bulak was built as a defence.

Turks and Ottomans

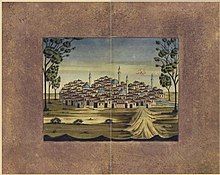

[edit]In the 11th century the Danishmend dynasty established Islam in Merzifon and the Byzantines never regained control. The Danishmends were followed by the Seljuk Turks, the Ilkhanids, and, from 1393 onwards, by the Ottomans. Merzifon was an important city for the Ottomans because of its proximity to Amasya (where Ottoman princes were raised and schooled for the throne). The Turkish travel writer Evliya Çelebi recorded it as a well-fortified trading city in the 17th century.

Merzifon was home to one of the last communities of Armenian Zoroastrians - known as Arewordik (children of the sun) - who are believed to have been killed in the Armenian genocide between 1915 and 1917.

By the 19th century Merzifon had become a centre for European trading and missionary activity, and American missionaries established a seminary here in 1862. In 1886, a school called the Anatolia College in Merzifon was founded (it expanded to serve girls in 1893). By 1914, the schools had over 200 boarding students, mostly ethnic Greeks and Armenians. The complex also had one of the largest hospitals in Asia Minor, and an orphanage housing 2000 children. However, the town also became a focal point for Armenian nationalism (Armenians comprised half of the population of what they called Marsovan in 1915) and anti-Western sentiment. It suffered at least two riots in the 1890s, but the damage was rebuilt. In 1915, over 11,000 Armenians were deported from the city (which had had approximately 30,000 inhabitants in the previous year) in death marches; others were killed and their property confiscated and sold to Turkish insiders, supposedly to benefit the Ottoman war effort, as documented by missionary George E. White. In addition, in 1915 several Greek men were murdered by the Ottomans, while the women were compelled to follow the Ottoman troops. Those who were exhausted after the long marches were abandoned with their babies on the roadside.[5] Following the Greco-Turkish War, the Merzifon College was closed and all the remaining Christians in Merzifon were forced to relocate to Greece where a new Anatolia College was opened in Thessaloniki in 1924

Turkish Republic

[edit]After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire at the end of the First World War, unrest continued. British troops were deployed in formerly Ottoman lands to ensure the terms of surrender, and some of them arrived in Merzifon in 1919 just as George White returned and reopened the college and orphanage, as well as a new "baby house" for displaced Armenian mothers and infants. However, the British troops soon withdrew and unrest continued in Merzifon.

Attractions

[edit]Merzifon's main attraction is the Merzifonlu Kara Mustafa Paşa Mosque, built in 1666 and featuring one of the lovely şadırvans (ablutions fountains) with internally painted domes for which the Amasya area is known. Much of the original mosque complex, including the hamam and the bedesten, survives and is still in use today.[6]

Notable natives

[edit]- Kara Mustafa Pasha (1634–1683) Ottoman grand vizier held responsible for the failure to conquer Vienna. The sultan received the report of this failure and ordered Kara Mustafa Pasha to have himself strangled. Being the obedient servant of the Ottoman Empire, he complied and was garotted with a silk cord in Belgrade on Christmas Day 1683.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2021" (XLS) (in Turkish). TÜİK. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 January 2023.

- ^ Özhan Öztürk. Pontus: Antik Çağ’dan Günümüze Karadeniz’in Etnik ve Siyasi Tarihi. Genesis Yayınları. Ankara, 2011. p.440. ISBN 978-605-54-1017-9.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Climate Normals for 1991-2020 — Merzifon". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ^ "ARMENIAN ATROCITIES". The North Western Advocate and The Emu Bay Times. Tasmania, Australia. 3 August 1915. p. 1. Retrieved 15 February 2021 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ "MERZİFONLU KARA MUSTAFA PAŞA KÜLLİYESİ". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2022-08-17.

External links

[edit]- Merzifon municipality's official website (in Turkish)

- Merzifonlu net (in Turkish)