Marshall Pinckney Wilder

Marshall Pinckney Wilder | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | September 19, 1859 Geneva, New York, U.S. |

| Died | January 10, 1915 (aged 55) St. Paul, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Occupation | Humorist |

| Years active | 1880–1915 |

| Spouse | Sophie Hanks |

| Children | 2 |

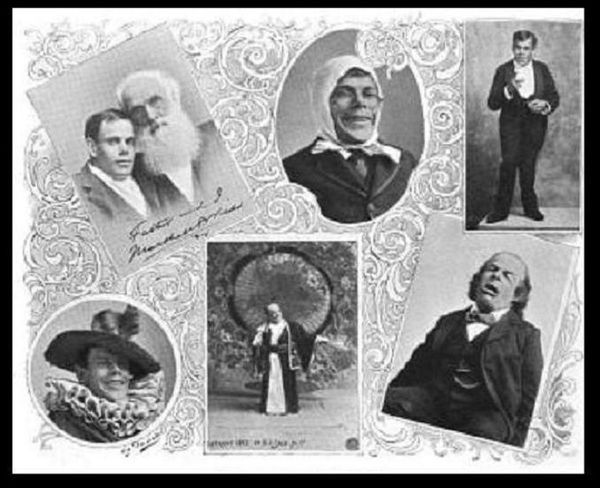

Marshall Pinckney Wilder (September 19, 1859 – January 10, 1915) was an American actor, monologist, humorist and sketch artist.

Early life

[edit]Marshall Pinckney Wilder (sometimes spelled Marshal) was born along the north shore of Seneca Lake at Geneva, New York,[1] the son of Dr. Louis de Valois Wilder and the former Mary A. Bostwick. He shared the same name as his great-uncle, a distinguished amateur pomologist and floriculturist who helped found the Boston Horticultural Society and American Pomological Society.[2][3] His father was an 1843 graduate of the Geneva Medical College and for a number of years an attending physician at Flower Hospital at the New York Medical College and a member of the New York Homeopathic Medical Society.[4]

While still a boy, Wilder's family moved to Rochester where he became popular for his talent as a storyteller and apparent gift as a clairvoyant. It was also at Rochester that Wilder received his early inspiration for a later vocation after attending a public reading at Corinthian Hall. In his youth he worked as a pin-boy at a bowling alley and storeroom clerk for a summer resort,[5] before moving to New York City around the age of twenty. He found employment as a file boy with a commercial firm. Wilder started augmenting his income by giving humorous monologues for 50 cents a performance.[1]

Career

[edit]These early performances held in the drawing rooms of wealthy New Yorkers gained him the notoriety to soon join the ranks of full-time entertainers.[5] In 1883 Wilder traveled to London where he became a favorite of the British royal family. While still the Prince of Wales, King Edward VII became an admirer of Wilder and over the years would attend nearly twenty of his performances. In 1888, Wilder joined The Lambs Club.[6] His career eventually branched into vaudeville and in 1904 embarked on a round the world tour.[7][8]

In describing his monologues the Syracuse Herald wrote in a 1907 article: "His pathos, his humor, his indescribable droll and uplifting optimism keeps bubbling forth all through the evening".[9]

Wilder, who always signed his correspondence "Merrily yours", authored three books over his career: The People I've Smiled With (1899),[10] The Sunnyside of the Street (1905), and Smiling Around the World (1908); and edited a number of volumes of The Wit and Humor of America and The Ten Books of the Merrymakers. The Washington Post wrote in 1915 of his coping with physical disabilities (dwarfism and kyphosis), "Wilder coaxed the frown of adverse fortune into a smile."[11][12]

Though nearly forgotten today, Wilder was heralded in his lifetime and did not let his dwarfism be an excuse for cheap entertainment. Wilder shunned offers by showmen like P.T. Barnum to instead become an established legitimate stage actor and sketch artist. He made his earliest motion picture appearance in 1897, for which he received $600,[13] and his last in 1913. Wilder also left recordings of his routines.[14]

At the end of each performance Wilder was known to seek out everyone involved in the show to shake their hand always with a generous tip in his palm. Wilder was until his final curtain call a headliner earning a five-figure annual income. At one point in his career Wilder was willing to take a cut in pay in order to play a vaudeville circuit he felt catered to an audience that better appreciated his humor. This did not happen, however, because of booking issues.[15][16]

Marriage

[edit]In 1903 Marshall Wilder married Sophie Cornell Hanks, the daughter of a New Jersey dentist. Sophie was a writer and dramatist who collaborated with Wilder on his books. Their daughter Grace was born in 1905 around the time the couple returned from the world tour. Marshall Jr. followed a year or so later. On December 20, 1913, Sophie died at the age of 35 in New York City after a brief illness and failed operation.[5] She was in the city to give dramatic readings of her new book, The Golden Lotus.[17]

Death

[edit]Following the loss of his wife, Wilder's health began to decline and a little over a year later fell ill while in St. Paul, Minnesota, for an engagement. His death there on January 10, 1915, was attributed to heart disease complicated by pneumonia.[1] The funeral service was held a few days later at the Stephen Merritt Mortuary Chapel in New York.[18] The writer and artist Elbert Hubbard wrote an obituary for Wilder which declared Wilder "picked up the lemons that Fate had sent him and started a lemonade-stand."[19] Marshal Wilder was survived by his children, who shared the bulk of his quarter-million-dollar estate,[12] and a sister, Jennie Cornelia Wilder, who also had some success as an entertainer of diminutive stature.[2]

During the Great Depression Grace Wilder served as director of the Puppets and Marionettes department of the Public Works Administration (PWA) Drama Division.[20] She would later serve in a similar capacity as a social worker in New York City [21] and with community puppet theaters in California.[22] According to one of his obituaries, puppetry was a childhood interest of her father's who would entertain his neighbors with Punch and Judy shows charging two cents admission or a nickel for reserved seating.[23]

Marshall P. Wilder Jr. (1913–1964) became a pioneer in the development of television when in 1931 he participated in the first successful transmission of a signal to a ship stationed some 50 miles offshore.[24] And later during World War II was one of the technicians who helped develop what today are called smart bombs by engineering a television camera small enough to fit into the nosecone of a bomb or unmanned aircraft that could be directed by remote control.[25]

Filmography

[edit]

- Marshall P. Wilder (1897)

- Actor's Fund Field Day (1910)

- Marshall P. Wilder (1912)(as himself)

- Chumps (1912)

- The Five Senses (1912)

- The Pipe (1912)

- The Greatest Thing in the World(1912)

- Professor Optimo (1912)

- Mockery (1912)

- The Godmother (1912)

- The Curio Hunters (1912)

- The Widow's Might (1913)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c The Syracuse Herald January 11, 1915, pg. 7

- ^ a b The New York Times February 17, 1933 pg. 19

- ^ History of Horticulture - Wilder, Marshall Pinckney 1798-1886 (Ohio State University)

- ^ Medical record, Volume 79 edited by George Frederick Shrady, Thomas Lathrop Stedman – 1911 pg. 309

- ^ a b c Appleton Post Crescent January 23, 1923 pg. 4

- ^ "The Lambs". the-lambs.org. The Lambs, Inc. 6 November 2015. (Member Roster). Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- ^ The Bookseller, Newsdealer and Stationer, Volume 42 – 1915- pg. 77

- ^ Who's Who on the Stage edited by Walter Browne, Frederick Arnold Austin 1908 pg 455 -

- ^ Syracuse Herald February 17, 1907 pg. 17

- ^ The People I’ve Smiled With at archive.org

- ^ January 15, 1915 pg. 3 (News Notes of the Stage)

- ^ a b The Oakland Tribune February 6, 1915 pg. 11

- ^ The Moving Picture World, Volume 27 By Moving Picture Exhibitors' Association 1916 pg. 1136

- ^ Marshall P. Wilder and Disability Performance History by Susan Schweik, University of California/Berkeley c.2010

- ^ The Lyceum magazine, Volume 29 edited by Ralph Albert Parlette 1919 pg. 44

- ^ The Kings of Jesters by Elbert Hubbard - The Fra: for Philistines and Roycrofters, Volume 14 edited by Elbert Hubbard, Felix Shay 1914 pg. viii

- ^ The Hartford Courant December 22, 1913

- ^ The New York Times January 12, 1915

- ^ "When life gives you lemons… delicious aphorisms and their interesting origins". The Irish Times.

- ^ The New York Times June 21, 1934 pg. 25

- ^ The New York Times October 11, 1944 pg.18

- ^ Oakland Tribune June 19, 1949 pg. 58

- ^ The Newark Advocate January 16, 1915 pg. 10

- ^ The New York Times September 9, 1931 pg. 55 – pg. 25

- ^ The Harford Courant October 28, 1945

External links

[edit]- Works by Marshall Pinckney Wilder at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Marshall Pinckney Wilder at the Internet Archive

- Works by Marshall Pinckney Wilder at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Marshall Pinckney Wilder at IMDb

- portrait gallery of Marshall P. Wilder(NY Public Library, Billy Rose collection)

- Marshall P. Wilder speaking in 1908 recording

- 1859 births

- 1915 deaths

- 19th-century American male actors

- American male stage actors

- American male silent film actors

- American non-fiction writers

- Male actors with dwarfism

- American actors with disabilities

- American expatriate male actors

- American expatriates in the United Kingdom

- American vaudeville performers

- Male actors from New York (state)

- Writers from New York (state)

- 20th-century American male actors

- People from Geneva, New York