Maʻopūtasi County

Maʻopūtasi County, American Samoa | |

|---|---|

| County of Maoputasi | |

Congregational Christian Church in Fagatogo | |

Map of Tutuila where Maʻopūtasi County is highlighted in red | |

| Country | |

| Territory | |

| Island | Tutuila |

| District | Eastern |

| Named for | O le Ma'upūtasi ("The Single Chief’s House") |

| County seat | Pago Pago |

| Largest city | Pago Pago |

| Area | |

• Total | 6.65 sq mi (17.2 km2) |

| Highest elevation | 2,142 ft (653 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 8,568 |

• Estimate (2015)[1] | 11,052 |

| • Density | 1,300/sq mi (500/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−11 (Pacific Time Zone) |

| ZIP code | 96799 |

| Area code | +1 684 |

Maʻopūtasi County is located in the Eastern District of Tutuila Island in American Samoa. Maʻopūtasi County comprises the capital of Pago Pago and its harbor, as well as surrounding villages. It was home to 11,695 residents as of 2000.[2] Maʻopūtasi County is 6.69 square miles (17.3 km2)[3] The county has a 7.42-mile (11.94 km) shoreline which includes Pago Pago Bay.[3]

Maʻopūtasi County makes up all villages in the Pago Pago Bay Area from Aua to Fatumafuti.[4] Besides Pago Pago, it is home to the following villages: Anua (2010 pop. 18), Atu’u (pop. 359), Aua (pop. 2,077), Faga'alu (pop. 910), Fagatogo (pop. 1,737), Fatumafuti (pop. 113), Leloaloa (pop. 448), Satala (pop. 297), and Utulei (pop. 684).[5]

Maʻopūtasi translates to “the only house of chiefs”.[6] Pago Pago has been called O le Maputasi ("The Single Chief’s House") in compliment to the Mauga, who lived at Gagamoe and was the senior to all the other chiefs in the area.[7]

The county is represented by three senators in the American Samoa Senate, and five representatives in the House of Representatives, more than any other county.[8] Following the 2018 midterm elections, the county is currently represented by the following five members in the House of Representatives: Vailoata Eteuati Amituana’i, Vailiuama Steve Leasiolagi, Vesiai Poyer Samuelu, Vaetasi Tuumolimoli Moliga, and Faimealelei Anthony Allen.[9]

History

[edit]

At the time of the Tuʻi Tonga Empire, the Tongans had established themselves in this area but were eventually driven off by chief Fua’autoa of Pago Pago in 1250.[10] During the Tongan rule, political opponents and defeated Samoan warriors were exiled to Pago Pago. Pago Pago and its surrounding settlements effectively functioned as a Samoan penal colony.[11]

In the summer of 1892, a disturbance broke out around Pago Pago Bay due to local rivalries. Mauga Lei chose to spend most of his time in Upolu Island, leaving the Pago Pago area without its natural leadership. The village of Pago Pago remained loyal, but neighboring Fagatogo joined with Aua village in an attempt to oust Mauga Lei in favor of a new titleholder. Pago Pago and the transmontane village of Fagasa demanded and received the surrender of the pretender. Fagatogans and Auans embarked in their boats and set out for Pago Pago, and when they were closing in on the village, they were met by bullets and forced to retreat. Houses were burned in Aua and Fagatogo, and women and children from Aua took refuge at the Roman Catholic Mission at Lepua.[12]

Following the death of elder statesman Mauga Moi Moi in 1935, the high chiefly title became vacant along with the county's chieftainship and the district's governorship. When the Mauga aiga could not agree upon a successor, the Governor had to fill administrative posts and named High Chief Lei’ato to be the district's governor. He decided to try free, “American-style” elections for the post of county chief, however, Aua village declined to take any part in such proceedings. In the fa'aSāmoa, Utulei and Fagatogo villages voted for the Mailo, but each of the other county villages voted for its own village chiefs. Five years later, when the Mauga aiga chose Sialega Palepoi to be their matai, and hence High Chief of Maputasi County, the county chieftainship passed naturally into his hands.[13]

The 2009 Samoa earthquake and tsunami did major structural damage to the port facility in Fagatogo and elsewhere in the county.[14][15]

Demographics

[edit]| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1912 | 1,264 | — |

| 1920 | 1,701 | +34.6% |

| 1930 | 2,559 | +50.4% |

| 1940 | 3,361 | +31.3% |

| 1950 | 5,467 | +62.7% |

| 1960 | 5,340 | −2.3% |

| 1970 | 7,886 | +47.7% |

| 1980 | 8,495 | +7.7% |

| 1990 | 10,640 | +25.3% |

| 2000 | 11,695 | +9.9% |

| 2010 | 10,299 | −11.9% |

| 2020 | 8,568 | −16.8% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] | ||

Ma'oputasi County was first recorded beginning with the 1912 special census. Regular decennial censuses were taken beginning in 1920.[17] From 1912 to 1970, it was reported as "Mauputasi County."

With the exception of Fatumafuti village, Maʻopūtasi County as a whole and all its villages experienced a population decline from 2000 to 2010. In 2010, the county was home to 10,299 residents, down from 11,695 recorded at the 2000 U.S. Census. Pago Pago’s population decreased 14.5 percent, Fagatogo’s population by 17.1 percent, and Utulei’s population by 15.2 percent. The population of the Eastern District decreased from 23,441 residents recorded at the 2000 U.S. Census, down to 23,030 residents as of the 2010 U.S. Census.[18]

Maʻopūtasi County had a 2015 population of 11,052 residents, according to the 2015 Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES) by the Commerce Department.[1] It is the second-most populated county (after Tualauta County) and was home to 1,999 housing units as of the 2010 U.S. Census, down from 2,031 recorded at the 2000 U.S. Census.[19] It had the second-highest number of registered voters in 2016, only surpassed by Tualauta County. However, during the 2016 elections, more votes were cast in Maʻopūtasi County than any other county. There were 3,507 registered voters in Maʻopūtasi County as of 2016: 1,911 females and 1,596 males.[20]

| Population change[18] | ||

|---|---|---|

| 2000 U.S. Census | 2010 U.S. Census | |

| Maʻopūtasi County | 11,695 | 10,299 |

| Anua | 265 | 18 |

| Atu'u | 413 | 359 |

| Aua | 2,193 | 2,077 |

| Faga'alu | 1,006 | 910 |

| Fagatogo | 2,096 | 1,737 |

| Fatumafuti | 103 | 113 |

| Leloaloa | 534 | 448 |

| Pago Pago (village) | 4,278 | 3,656 |

| Satala | - | 297 |

| Utulei | 807 | 684 |

Landmarks

[edit]

- American Samoa Fono, the American Samoa legislature in Fagatogo

- Blunts Point Battery, National Historic Landmark on Matautu Ridge in Utulei

- Breakers Point Naval Guns, World War II-era defensive fortification, listed on the National Register of Historic Places

- Church of the Sacred Heart, in Anua

- Co-Cathedral of St. Joseph the Worker, the Roman Catholic cathedral of American Samoa, in Fagatogo

- Courthouse of American Samoa, in Utulei, listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Fagatogo Market, a marketplace in downtown Fagatogo

- Fagatogo Square Shopping Center, 12,000 sq. ft. retail- and commercial center

- Feleti Barstow Public Library, central public library for American Samoa, in Utulei

- Flowerpot Rock, national landmark by Fatumafuti

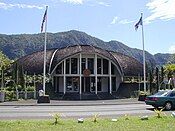

- Governor H. Rex Lee Auditorium ("Turtle House"), in Utulei, listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Government House, historic government building on the grounds of the former Naval Station Tutuila in Pago Pago

- Jean P. Haydon Museum, a museum in Fagatogo listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Lyndon B. Johnson Tropical Medical Center, only hospital in American Samoa, in Faga'alu

- Michael J. Kirwan Educational Television Center, in Utulei, listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- National Park of American Samoa

- Navy Building 38, in Fagatogo, listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Rainmaker Hotel, former luxury hotel in Utulei

- Rainmaker Mountain, designated National Natural Landmark

- Sadie Thompson Inn, Fagatogo hotel listed on the U.S. National Register of Historic Places

- Tauese PF Sunia Ocean Center, visitor center for National Marine Sanctuary of American Samoa

- U.S. Naval Station Tutuila Historic District, in Fagatogo

- Utulei Beach Park, park in Utulei

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Taulauta faipule Vui seeks to amend Constitution to add two more seats for her district | American Samoa". Samoa News. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ Government Printing Office (2004). The National Data Book. Government Printing Office. Page 824. ISBN 9780160877575.

- ^ a b "Mitigatio plan" (PDF). www.wsspc.org. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ "Lawmakers hear 'options' on the House reapportionment issue | American Samoa". Samoa News. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ "Census data" (PDF). www.census.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 436. ISBN 9780824822194.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1980). Amerika Samoa. Arno Press. Page 123. ISBN 9780405130380.

- ^ "American samoa". Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ "American samoa". Archived from the original on 2019-03-21. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- ^ Krämer, Augustin (2000). The Samoa Islands. University of Hawaii Press. Page 436. ISBN 9780824822194.

- ^ Todd, Ian (1974). Island Realm: A Pacific Panorama. Angus & Robertson. Page 69. ISBN 9780207127618.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1980). Amerika Samoa. Arno Press. Pages 95-96. ISBN 9780405130380.

- ^ Gray, John Alexander Clinton (1980). Amerika Samoa. Arno Press. Page 238. ISBN 9780405130380.

- ^ "Tsunami in Samoa Islands - Charter Activations - International Disasters Charter". Archived from the original on 2017-10-21. Retrieved 2017-10-21.

- ^ "Fa'alauiloa galuega mo le toe fa'aleleia uafu o va'a fagota alia i Fagatogo". Samoa News.

- ^ "U.S. Decennial Census". Census.gov. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- ^ "Census" (PDF). www.census.gov. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ a b "Population and Annual Growth Rate". American Samoa Department of Commerce. Retrieved September 17, 2019.

- ^ "2010 census reveals jump in local housing units | American Samoa". Samoa News. 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2020-01-21.

- ^ "Election Office stats show registered female voters outnumber male voters | American Samoa". Samoa News. 2016-11-08. Retrieved 2020-01-21.