Western Neo-Aramaic

| Western Neo-Aramaic | |

|---|---|

| ܣܪܝܘܢ (ܐܰܪܳܡܰܝ) siryōn (arōmay) | |

| Pronunciation | [sirˈjo:n] |

| Native to | Syria |

| Region | Bab Touma District, Damascus; Anti-Lebanon Mountains: Maaloula, Bakhʽa and Jubb'adin |

| Ethnicity | Aramean (Syriac)[1][2] |

Native speakers | 30,000 (2023)[3] |

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms | |

| Dialects |

|

| Maalouli square script[a] Syriac alphabet (Serṭā) Phoenician alphabet[b] Arabic alphabet | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | amw |

| Glottolog | west2763 |

| ELP | Western Neo-Aramaic |

Western Neo-Aramaic (ܐܰܪܳܡܰܝ, arōmay, "Aramaic"), more commonly referred to as Siryon[4] (ܣܪܝܘܢ, siryōn, "Syriac"),[5][6][7] is a modern variety of the Western Aramaic branch consisting of three closely related dialects.[8] Today, it is spoken by Christian and Muslim Arameans (Syriacs)[9][10][11][12][13][14][15] in only three villages – Maaloula, Jubb'adin and Bakhʽa – in the Anti-Lebanon mountains of western Syria.[16] Bakhʽa was vastly destroyed during the war and most of the community fled to other parts of Syria or Lebanon.[17] Western Neo-Aramaic is believed to be the closest living language to the language of Jesus, whose first language, according to scholarly consensus, was Galilean Aramaic belonging to the Western branch as well; all other remaining Neo-Aramaic languages are Eastern Aramaic.[18]

Distribution and history

[edit]Western Neo-Aramaic is the sole surviving remnant of the once extensive Western Aramaic-speaking area, which also included the Palestine region and Lebanon in the 7th century.[19] It is now spoken exclusively by the inhabitants of Maaloula and Jubb'adin, about 60 kilometres (37 mi) northeast of Damascus. The continuation of this little cluster of Aramaic in a sea of Arabic is partly due to the relative isolation of the villages and their close-knit Christian and Muslim communities.

Following the Muslim conquest of the Levant, there was a linguistic shift to Arabic for local Muslims and later for remaining Christians; Arabic displaced various Aramaic dialects, including Western Aramaic varieties, as the first language of the majority. Despite this, Western Aramaic appears to have survived for a relatively long time at least in some remote mountain villages in Lebanon and Anti-Lebanon. In fact, up until the 17th century, travelers in Lebanon still reported on several Aramaic-speaking villages.[20]

The dialect of Bakhʽa was the most conservative. Arabic less influenced it than the other dialects and retains some vocabulary that is obsolete in other dialects. The dialect of Jubb'adin changed the most. Arabic heavily influenced it and has a more developed phonology. The dialect of Maaloula is somewhere in between the two, but closer to that of Jubb'adin.[citation needed]

The cross-linguistic influence between Aramaic and Arabic has been mutual, as Syrian Arabic itself (and Levantine Arabic in general) retains an Aramaic substratum.[21] Similar to the Eastern Neo-Aramaic languages, Western Neo-Aramaic uses Kurdish loanwords unlike other Western Aramaic dialects, e. g. in their negation structure: "Čū ndōmex", meaning "I do not sleep" in the Maalouli dialect.[22][23] These influences might indicate an older historical connection between Western Neo-Aramaic and Eastern Aramaic speakers.[24] Other strong linguistic influences on Western Neo-Aramaic include Akkadian during the Neo-Babylonian period, e. g. the names of the months: āšbaṭ (Akk. šabāṭu, "February"), ōḏar (Akk. ad(d)aru, "March"), iyyar (Akk. ayyaru, "May") or agricultural terms such as nīra (Akk. nīru, "yoke"), sekkṯa (Akk. sikkatu, "plowshare"), senta (Akk. sendu, "to grind") or nbūba (Akk. enbūbu, "fruit").[25][26]

As in most of the Levant before the introduction of Islam in the seventh century, the three villages were originally all Christian until the 18th century.[27][28] Maaloula is the only village that retains a sizeable Melkite Christian population belonging to the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Antioch and Melkite Greek Catholic Church; the inhabitants of Bakhʽa and Jubb’adin converted to Islam over the generations. However, the first Muslims were not native converts, but Arab families from Homs who were settled in the villages during the Ottoman era to monitor the Christian population.[29] Maaloula glows in the pale blue wash with which houses are painted every year in honor of Mary, mother of Jesus.[citation needed]

Historical accounts, as documented by the French linguist Jean Parisot in 1898, suggest that the people of Maaloula and nearby areas claim to be descendants of migrants from the Sinjar region (modern Iraq). According to their oral traditions, their ancestors embarked on a substantial migration in ancient times, driven by the challenges posed by the Muslim occupation of the northern part of Mesopotamia. Seeking refuge, they crossed the Euphrates and traversed the Palmyrene desert, eventually finding a lasting sanctuary among Western Aramaic-speaking communities in the highlands of eastern Syria.[c][30] In Maaloula and the surrounding villages, the surname ”Sinjar“ (Aramaic:ܣܢܓܐܪ) is borne by some Christian and Muslim families.[31]

All three remaining Western Neo-Aramaic dialects are facing critical endangerment as living languages. As with any village community in the 21st century, young residents are migrating into major cities like Damascus and Aleppo in search of better employment opportunities, thus forcing them into monolingual Arabic-speaking settings, in turn straining the opportunity to actively maintain Western Neo-Aramaic as a language of daily use. Nevertheless, the Syrian government provides support for teaching the language.[32]

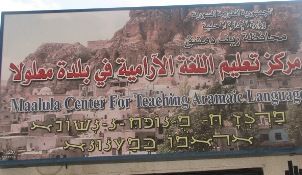

Unlike Syriac, which has a rich literary tradition, Western Neo-Aramaic was solely passed down orally for generations until 2006 and was unwritten.[33] Since 2006, Maaloula has been home to an Aramaic language institute established by the Damascus University that teaches courses to keep the language alive. The institute's activities were suspended in 2010 amid concerns that the square Maalouli Aramaic alphabet used in the program, which was developed by the chairman of the language institute, George Rizkalla (Rezkallah), resembled the square script of the Hebrew alphabet. Consequently, all signs featuring the square Maalouli script were taken down.[34] The program stated that they would instead use the more distinct Syriac alphabet, although use of Maalouli square script has continued to some degree.[35] Al-Jazeera Arabic also broadcast a program about Western Neo-Aramaic and the villages in which it is spoken with the square script still in use.[36]

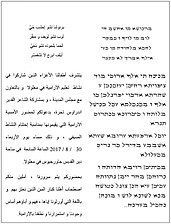

In December 2016, during an Aramaic Singing Festival in Maaloula, a modified version of an older style of the Aramaic alphabet closer to the Phoenician alphabet was used for Western Neo-Aramaic. This script seems to be used as a true alphabet with letters to represent both consonants and vowels instead of the traditional system of the Aramaic alphabet where it is used as an abjad. A recently published book about the Maalouli Aramaic dialect also uses this script.[37][38]

Aramaic Bible Translation (ABT) has spent over a decade translating the Bible into Maalouli Western Neo-Aramaic and recording audio for Portrait of Jesus. Rinyo, the Syriac language organization, has published ABT's content, developed by Kanusoft.com. On their website, the Book of Psalms and Portrait of Jesus are available in Western Neo-Aramaic using the Syriac Serta script. Additionally, a New Testament translation into Western Neo-Aramaic was completed in 2017 and is now accessible online.[39][40][41]

An electronic speech corpus of Maalouli Western Neo-Aramaic has been available online since 2022.[42][43]

Phonology

[edit]The phonology of Western Neo-Aramaic has developed quite differently from other Aramaic dialects/languages. The labial consonants of older Western Aramaic, /p/ and /f/, have been retained in Bakhʽa and Maaloula while they have mostly collapsed to /f/ in Jubb'adin under influence from Arabic. The labial consonant pair /b~v/ has collapsed to /b/ in all three villages. Amongst dental consonants, the fricatives /θ ð/ are retained while /d/ have become /ð/ in most places and /t/, while remaining a phoneme, has had its traditional position in Aramaic words replaced by /ts/ in Bakhʽa, and /tʃ/ in Maaloula and Jubb'adin. However, [ti] is the usual form for the relative particle in these two villages, with a variant [tʃi], where Bakhʽa always uses [tsi]. Among the velar consonants, the traditional voiced pair of /ɡ ɣ/ has collapsed into /ɣ/, while /ɡ/ still remains a phoneme in some words. The unvoiced velar fricative, /x/, is retained, but its plosive complement /k/, while also remaining a distinct phoneme, has in its traditional positions in Aramaic words started to undergo palatalization. In Bakhʽa, the palatalization is hardly apparent; in Maaloula, it is more obvious, and often leads to [kʲ]; in Jubb'adin, it has become /tʃ/, and has thus merged phonemically with the original positions of /t/. The original uvular plosive, /q/, has also moved forward in Western Neo-Aramaic. In Bakhʽa it has become a strongly post-velar plosive, and in Maaloula more lightly post-velar. In Jubb'adin, however, it has replaced the velar plosive, and become /k/. Its phonology is strikingly similar to Arabic both being sister Semitic languages.

Consonants

[edit]| Labial | Dental/Alveolar | Palato- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyn- geal |

Glottal | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nasal | m | n | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Plosive | p | b | t | d | tˤ | (kʲ) | k | ɡ | q | ʔ | ||||||||||||

| Affricate | (ts) | (tʃ | dʒ) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Fricative | f | θ | ð | s | z | ðˤ | sˤ | zˤ | ʃ | (ʒ) | x | ɣ | ħ | ʕ | h | |||||||

| Approximant | w | l | j | |||||||||||||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||||||||||||||

Vowels

[edit]Western Neo-Aramaic has the following set of vowels:[44]

| Front | Back | |

|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u |

| Open-mid | e | o |

| Open | a | |

Alphabet

[edit]Square Maalouli alphabet

[edit]This article possibly contains original research. (March 2022) |

Square Maalouli alphabet used for Western Neo-Aramaic.[45] Words beginning with a vowel are written with an initial ![]() . Short vowels are omitted or written with diacritics, long vowels are transcribed with macrons (Āā, Ēē, Īī, Ōō, Ūū) and are written with mater lectionis (

. Short vowels are omitted or written with diacritics, long vowels are transcribed with macrons (Āā, Ēē, Īī, Ōō, Ūū) and are written with mater lectionis (![]() for /o/ and /u/,

for /o/ and /u/, ![]() for /i/, which are also used at the end of a word if it ends with one of these vowels and if a word begins with any of these long vowels, they begin with

for /i/, which are also used at the end of a word if it ends with one of these vowels and if a word begins with any of these long vowels, they begin with ![]() + the mater lectionis). Words ending with /a/ are written with

+ the mater lectionis). Words ending with /a/ are written with ![]() at the end of the word, while words ending with /e/ are written with

at the end of the word, while words ending with /e/ are written with ![]() at the end. Sometimes

at the end. Sometimes ![]() is used both for final

is used both for final ![]() and

and ![]() instead of also using

instead of also using ![]() .

.

| Maalouli letter: | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hebrew letter: | א | בּ | ב | גּ | ג | דּ | ד | ה | ו | ז | ח | ט | י | כּ ךּ | כ ך | ל | מ ם | נ ן | ס | ע | פּ ףּ | פ ף | צ ץ | ק | ר | שׁ | תּ | ת | ת |

| Latin letter/Transliteration | Aa, Ee, Ii, Oo, Uu Āā, Ēē, Īī, Ōō, Ūū |

Bb | Vv | Gg | Ġġ | Dd | Ḏḏ | Hh | Ww | Zz | Ḥḥ | Ṭṭ | Yy | Kk | H̱ẖ | Ll | Mm | Nn | Ss | Ҁҁ | Pp | Ff | Ṣṣ | Rr | Šš | Tt | Ṯṯ | Čč | |

| Pronunciation | ∅ | /b/ | /v/ | /g/, /ʒ/ | /ɣ/ | /d/ | /ð/ | /h/ | /w/ | /z/ | /ħ/ | /tˤ/ | /j/ | /k/ | /x/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /s/ | /ʕ/ | /p/ | /f/ | /sˤ/ | /k/~/ḳ/ | /r/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ | /θ/ | /tʃ/ |

Syriac and Arabic alphabet

[edit]Syriac (Serta) and Arabic alphabet used for Western Neo-Aramaic.[46]

| Syriac letter: | ܐ | ܒ | ܒ݆ | ܓ | ܔ | ܓ݂ | ܕ | ܕ݂ | ܗ | ܘ | ܙ | ܚ | ܚ݂ | ܛ | ܜ | ܝ | ܟ | ܟ݂ | ܠ | ܡ | ܢ | ܣ | ܥ | ܦ | ܨ | ܨ̇ | ܩ | ܪ | ܫ | ܬ | ܬ݂ | ܬ̤ |

| Arabic letter: | ا | ب | پ | گ | ج | غ | د | ذ | ه | و | ز | ح | خ | ط | ظ | ي | ک | خ | ل | م | ن | س | ع | ف | ص | ض | ق | ر | ش | ت | ث | چ |

| Pronunciation | /ʔ/, ∅ | /b/ | /p/ | /g/ | /dʒ/ | /ɣ/ | /d/ | /ð/ | /h/ | /w/ | /z/ | /ħ/ | /x/ | /tˤ/ | /dˤ/ | /j/ | /k/ | /x/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /s/ | /ʕ/ | /f/ | /sˤ/ | /ðˤ/ | /q/~/ḳ/ | /r/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ | /θ/ | /tʃ/ |

| Syriac letter: | ܰ | ܶ | ܳ | ܺ | ܽ |

| Arabic letter: | ـَ | ـِ | ـُ | ي | و |

| Pronunciation | /a/ | /e/ | /o/ | /i/ | /u/ |

Alternate Aramaic alphabet

[edit]Characters of the script system similar to the Old Aramaic or Phoenician alphabet used occasionally for Western Neo-Aramaic with matching transliteration. The script is used as a true alphabet with distinct letters for all phonemes including vowels instead of the traditional abjad system with plosive-fricative pairs.[47][38]

| Letter | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Transliteration | b | ġ | ḏ | h | w | z | ḥ | ṭ | y | k | x | l | m | n | s | ʕ | p | f | ṣ | ḳ | r | š | t | ṯ | č | ž | ᶄ | ḏ̣ | ẓ | ' |

| Pronunciation | /b/ | /ɣ/ | /ð/ | /h/ | /w/ | /z/ | /ħ/ | /tˤ/ | /j/ | /k/ | /x/ | /l/ | /m/ | /n/ | /s/ | /ʕ/ | /p/ | /f/ | /sˤ/ | /k/~/ḳ/ | /r/ | /ʃ/ | /t/ | /θ/ | /tʃ/ | /ʒ/ | /kʲ/ | /ðˤ/ | /dˤ/ | /ʔ/ |

| Letter | |||||||||||

| Transliteration | a | ā | e | ē | i | ī | o | ō | u | ū | ᵊ |

| Pronunciation | /a/ | /a:/ | /e/ | /e:/ | /i/ | /i:/ | /o/ | /o:/ | /u/ | /u:/ | /ə/ |

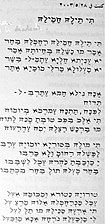

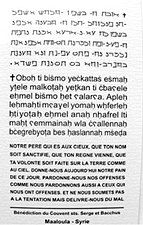

Liturgical language and sample of Lord's Prayer

[edit]Lord's Prayer in Western Neo-Aramaic, Turoyo Neo-Aramaic, Classical Syriac (Eastern accent) and Hebrew.

There are various versions of the Lord's Prayer in Western Neo-Aramaic, incorporating altered loanwords from several languages, notably Arabic: Šēḏa (from Akk. šēdu, meaning "evil" or "devil"),[48] yiṯkan (from Ar. litakun, meaning "that it may be" or "to be"), ġfurlēḥ & nġofrin (from Ar. yaghfir, meaning "to forgive") and čaġribyōṯa (from Ar. jareeb, meaning "temptation").[49]

Several decades ago, the Christian inhabitants of Maaloula began translating Christian prayers and texts into their vernacular Aramaic dialect, given that their actual liturgical languages are Arabic and Koine Greek.

Pastor Edward Robinson reported that his companion, Eli Smith, found several manuscripts in the Syriac language in Maaloula in 1834, but no one could read or understand them.[50] Classical Syriac, the Aramaic dialect of Edessa, was utilized as the liturgical language by local Syriac Melkite Christians following the Byzantine rite. There was a compilation of Syriac manuscripts from the monasteries and churches of Maaloula. However, a notable portion of these manuscripts met destruction upon the directives of a bishop in the 19th century.[51][52][53][54]

| Western Neo-Aramaic | Turoyo Neo-Aramaic | Classical Syriac (Eastern accent) | Hebrew |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ōboḥ/Ōbay/Abūnaḥ ti bišmō/bišmoya yičqattaš ešmaẖ | Abuna d-këtyo bišmayo miqadeš ešmoḵ | Aḇūn d-ḇa-šmayyāʾ neṯqaddaš šmāḵ | Avinu šebašamayim yitkadeš šimḵa |

| yṯēle molkaẖ/malkuṯaẖ yiṯkan ti čbaҁēleh | g-dëṯyo i malkuṯayḏoḵ howe u ṣebyonayḏoḵ | tēṯēʾ malkūṯāḵ nēhwēʾ ṣeḇyānāḵ | tavo malḵutḵa, ya'aseh retsonẖa |

| iẖmel bišmō/bišmoya ẖet ҁalarҁa. | ḵud d'kit bi šmayo hawḵa bi arҁo ste | ʾaykannāʾ d-ḇa-šmayyāʾ ʾāp̄ b-ʾarʿāʾ. | kevašamayim ken ba'arets. |

| Aplēḥ leḥmaḥ uẖẖil yōmaḥ | Haw lan u laḥmo d-sniquṯayḏan adyawma | Haḇ lan laḥmāʾ d-sūnqānan yawmānā | Et leẖem ẖukenu ten lanu hayom |

| ġfurlēḥ ḥṭiyōṯaḥ eẖmil | wa šbaq lan a-ḥṭohayḏan ḵud d-aḥna ste | wa-šḇōq lan ḥawbayn wa-ḥṭāhayn | uselaẖ lanu al ẖata'enu |

| nġofrin lti maḥiṭ ҁemmaynaḥ | sbaq lan lanek laf elan | ʾaykanāʾ d-āp̄ ḥnan šḇaqn l-ḥayāḇayn | kefi šesolẖim gam anaẖnu laẖot'im lanu |

| wlōfaš ttaẖlennaḥ bčaġribyōṯa | w lo maҁbret lan l'nesyuno | w-lāʾ taʿlan l-nesyōnāʾ | ve'al tavienu lide nisayon |

| bes ḥaslannaḥ m-šēḏa | elo mfaṣay lan mu bišo | ʾelāʾ paṣān men bīšāʾ | ki im ẖaltsenu min hara |

| English | Western Neo-Aramaic |

|---|---|

| Hello/Peace | šlōma |

| Altar server | šammōša |

| Morning | ṣofra |

| Mountain | ṭūra |

| Water | mōya |

| God | alo (defined)/iloha (undefined) |

| Sun | šimša |

| Mouth | femma |

| Head | rayša |

| Village | qriṯa |

| I swear (by the Cross) | bsliba |

| Nice | ḥalya |

| Here/Here it is | hōxa/hōxa hū |

| Liar | daglōna |

| After | bōṯar min |

| Son | ebra |

| Daughter | berča |

| Brother/Brothers | ḥōna/ḥuno |

| Sister | ḥōṯa |

| Donkey | ḥmōra |

| Tongue/Language | liššōna |

| Money | kiršo |

| Nation | omṯa |

| Year | ešna |

| Moon | ṣahra |

| King | malka |

| Earth | arʕa |

| Dove | yawna |

| Long live! | tiḥi! |

| Grave | qabra |

| Food | xōla |

| (Paternal) Uncle | ḏōḏa |

| (Maternal) Uncle | ḥōla |

| (Paternal) Aunt | ʕamṯa |

| (Maternal) Aunt | ḥōlča |

| Father | ōbu |

| Mother | emma |

| My mother | emmay (lit. "my mothers", archaic phrase) |

| Grandfather | žetta |

| Grandmother | žičča |

| Way | tarba |

| Ocean | yamma |

| Congratulations! | ibrex! |

| Aramean (Syriac) | sūray |

| Sky | šmōya/šmō |

| Who? | mōn? |

| Love | rḥmōṯa |

| Kiss | nōšqṯa |

| How are you? | ex čōb? (m)/ex čiba? (f) |

| Fast | ṣawma |

| Human | barnōša |

| Holy Spirit | ruḥa qutšō |

| Poison | samma |

| Sword | seyfa |

| Bone | ġerma |

| Blood | eḏma |

| Half | felka |

| Skin | ġelta |

| Hunger | xafna |

| Stone/Rock | xefa |

| Vineyard | xarma |

| Back | ḥaṣṣa |

| Goat | ʕezza |

| Lip | sefta |

| Chin/Beard | ḏeqna |

| Tooth/Crag | šenna |

| Past | zibnō |

| Queen | malkṯa |

| The little man | ġabrōna zʕōra |

| Peace to all of you | šlōma lxulḥun |

| Who is this? | mōn hanna? (m)/mōn hōḏ? (f) |

| I am Aramean (Syriac) and my language is Aramaic (Syriac) | ana sūray w lišōni siryōn |

| We are Arameans (Syriacs) and our language is Aramaic (Syriac) | anaḥ suroy w lišonaḥ siryōn |

| Church | klēsya (Greek loanword) |

| Shirt | qameṣča (from lat. "camisia") |

| What's your name? (m) | mō ušmax? (m) |

| Dream | ḥelma |

| Old man | sōba |

Gallery

[edit]See also

[edit]- Eugen Prym

- Albert Socin

- Arameans

- Aram-Damascus

- Aramaic studies

- Bible translations into Aramaic

- Neo-Aramaic languages

Literature

[edit]- Arnold, Werner: Das Neuwestaramäische (Western Neo-Aramaic), 6 volumes. Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden (Semitica Viva 4),

- Volume 1: Texte aus Baxʿa (Texts from Baxʿa), 1989, ISBN 3-447-02949-8,

- Volume 2: Texte aus Ğubbʿadīn (Texts from Ğubbʿadīn), 1990, ISBN 3-447-03051-8,

- Volume 3: Volkskundliche Texte aus Maʿlūla (Texts of folk tradition from Maʿlūla), 1991, ISBN 3-447-03166-2,

- Volume 4: Orale Literatur aus Maʿlūla (Oral Literature from Maʿlūla), 1991, ISBN 3-447-03173-5,

- Volume 5: Grammatik (Grammar), 1990, ISBN 3-447-03099-2,

- Volume 6: Wörterbuch (Dictionary), 2019, ISBN 978-3-447-10806-5,

- Arnold, Werner. 1990. New materials on Western Neo-Aramaic. In Wolfhart Heinrichs (ed.), Studies in Neo-Aramaic, 131–149. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press.

- Arnold, Werner. 2002. Neue Lieder aus Maʿlūla. In Werner Arnold & Hartmut Bobzin (eds.), „Sprich doch mit deinen Knechten aramäisch, wir verstehen es!” 60 Beiträge zur Semitistik. Festschrift für Otto Jastrow zum 60. Geburtstag., 31–52. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Arnold, Werner: Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (A Manual to Western Neo-Aramaic), Harrassowitz, Wiesbaden 1989, ISBN 3-447-02910-2.

- Arnold, Werner. 2008. The begadkephat in Western Neo-Aramaic. In Geoffrey Khan (ed.), Neo-Aramaic dialect studies, 171–176. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press. https://doi.org/10.31826/9781463211615-011.

- Arnold, Werner. 2011. Western Neo-Aramaic. In Stefan Weninger, Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck & Janet C. E. Watson (eds.), The Semitic languages. An international handbook, 685–696. Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter Mouton. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110251586.685.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1915. Neuaramäische Märchen und andere Texte aus Maʿlūla. Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus. https://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/publicdomain/content/titleinfo/857071.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1918. Neue Texte im aramäischen Dialekt von Maʿlula. In Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und verwandte Gebiete, vol. 32, 103–163. https://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/dmg/periodical/titleinfo/118493.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1928. Einführung in die semitischen Sprachen. Sprachproben und grammatische Skizzen. Munich: Max Hueber. https://menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de/publicdomain/content/titleinfo/597992.

- Bergsträsser, Gotthelf. 1933. Phonogramme im neuaramäischen Dialekt von Malula. Satzdruck und Satzmelodie. Munich: Verlag der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Correll, Christoph. 1978. Untersuchungen zur Syntax der neuwestaramäischen Dialekte des Antilibanon: (Maʿlūla, Baḫʿa, ǦubbʿAdīn); mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der Auswirkungen arabischen Adstrateinflusses; nebst zwei Anhängen zum neuaramäischen Dialekt von ǦubbʿAdīn. (Abhandlungen Für Die Kunde Des Morgenlandes 44/4). Wiesbaden: Steiner.

- Eid, Ghattas. 2024. The Phonology of Maaloula Aramaic. Düsseldorf: Düsseldorf University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783111447124.

- Eid, Ghattas & Ingo Plag. 2024. Syllable structure and syllabification in Maaloula Aramaic. Lingua 297. 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2023.103612.

- Eid, Ghattas, Esther Seyffarth & Ingo Plag. 2022. The Maaloula Aramaic Speech Corpus (MASC): From printed material to a lemmatized and time-aligned corpus. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2022), 6513–6520. Marseille. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2022/pdf/2022.lrec-1.699.pdf.

- Reich, Sigismund. 1937. Études sur les villages araméens de l’Anti-Liban (Documents d’Études Orientales 7). Damascus: Institut Français de Damas.

- Spitaler, Anton. 1938. Grammatik des neuaramäischen Dialekts von Maʿlūla (Antilibanon). Leipzig: F.A. Brockhaus. http://dx.doi.org/10.25673/36802.

- Spitaler, Anton. 1957. Neue Materialien zum aramäischen Dialekt von Maʿlūla. Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft 107(2). 299–339.

- Wehbi, Rimon (2021). "Zwei neuwestaramäische Texte über die Wassermühlen in Maalula (Syrien)". Mediterranean Language Review. 28: 135–153. doi:10.13173/medilangrevi.28.2021.0135. S2CID 245214675.

Notes

[edit]- ^ It is a modified version of the Hebrew alphabet since 2006, but its usage is declining.

- ^ Since 2016, a rarely utilized, slightly modified version of the Old Phoenician alphabet has been used for Western Neo-Aramaic.

- ^ The Anti-Lebanon mountains were geographically located in the eastern part of former Ottoman Syria in the year 1898, thus Jean Parisot wrote, "highlands of eastern Syria".

References

[edit]- ^ Abū al-Faraj ʻIshsh. اثرنا في الايقليم السوري (in Arabic). Al-Maṭbaʻah al-Jadīdah. p. 56.

السريان في معلولا وجبعدين ولا يزال الأهلون فيها يتكلمون

- ^ iنصر الله، إلياس أنطون. إلياس أنطون نصر الله في معلولا (in Arabic). لينين. p. 45.

... معلولا السريان منذ القديم ، والذين ثبتت سريانيتهم بأدلة كثيرة هم وعين التينة وبخعا وجبعدين فحافظوا على لغتهم وكتبهم أكثر من غيرهم . وكان للقوم في تلك الأيام لهجتان ، لهجة عاميّة وهي الباقية الآن في معلولا وجوارها ( جبعدين وبخعا ) ...

- ^ Western Neo-Aramaic at Ethnologue (27th ed., 2024)

- ^ Daniel King (12 December 2018). The Syriac World. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317482116.

There are no significant differences in the dialect of Malula between the speech of Christians and Muslims. The native name is siryōn or arōmay.

- ^ Jules Ferrette (1863). On a Neo-Syriac language still spoken in the Anti-Lebanon. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain. p. 433.

I then requested them to translate for me the Lord's Prayer into Ma'lulan Syriac for me; but a universal outcry was raised from every side as to the exorbitant nature of my demand. Some of the priests affirmed, ex cathedra, that not only had the Lord's Prayer never been uttered in modern Syriac, but that to translate it would be a mere impossibility.

- ^ Western Neo-Aramaic: The Dialect of Jubaadin , p. 446

- ^ Maaloula (XIXe-XXIe siècles). Du vieux avec du neuf, p. 95

- ^ From a Spoken to a Written Language. p. 3. ISBN 9789062589814.

Western Neo-Aramaic. This group consists of the dialects of the three villages Ma'lula, Bax'a, and Jubb'adin in western Syria. It is the only remnant of the dialects of Western Aramaic in the earlier periods.

- ^ Rafik Schami (25 July 2011). Märchen aus Malula (in German). Carl Hanser Verlag GmbH & Company KG. p. 151. ISBN 9783446239005.

Ich kenne das Dorf nicht, doch gehört habe ich davon. Was ist mit Malula?‹ fragte der festgehaltene Derwisch. >Das letzte Dorf der Aramäer< lachte einer der…

- ^ Yaron Matras; Jeanette Sakel (2007). Grammatical Borrowing in Cross-Linguistic Perspective. De Gruyter. p. 185. doi:10.1515/9783110199192. ISBN 9783110199192.

The fact that nearly all Arabic loans in Ma'lula originate from the period before the change from the rural dialect to the city dialect of Damascus shows that the contact between the Aramaeans and the Arabs was intimate…

- ^ Dr. Emna Labidi (2022). Untersuchungen zum Spracherwerb zweisprachiger Kinder im Aramäerdorf Dschubbadin (Syrien) (in German). LIT. p. 133. ISBN 9783643152619.

Aramäer von Ǧubbˁadīn

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold; P. Behnstedt (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 42. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die arabischen Dialekte der Aramäer

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold; P. Behnstedt (1993). Arabisch-aramäische Sprachbeziehungen im Qalamūn (Syrien) (in German). Harassowitz. p. 5. ISBN 9783447033268.

Die Kontakte zwischen den drei Aramäer-dörfern sind nicht besonders stark.

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 133. ISBN 9783447053136.

Aramäern in Ma'lūla

- ^ Prof. Dr. Werner Arnold (2006). Lehrbuch des Neuwestaramäischen (in German). Harrassowitz. p. 15. ISBN 9783447053136.

Viele Aramäer arbeiten heute in Damaskus, Beirut oder in den Golfstaaten und verbringen nur die Sommermonate im Dorf.

- ^ "Brock Introduction" (PDF). meti.byu.edu.

- ^ Al-Tamimi, Aymenn Jawad (2020-01-26). "The Village of Bakh'a in Qalamoun: Interview". Aymenn Jawad Al-Tamimi. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ "Easter Sunday: A Syrian bid to resurrect Aramaic, the language of Jesus Christ". Christian Science Monitor. 2010-04-02. ISSN 0882-7729. Retrieved 2022-11-07.

- ^ Jared Greenblatt (7 December 2010). The Jewish Neo-Aramaic Dialect of Amədya. Brill. p. 2. ISBN 9789004192300.

…. 7th century C.E. initiated the demise of the Aramaic language….

- ^ Owens, Jonathan (2000). Arabic as a Minority Language. Walter de Gruyter. p. 347. ISBN 3-11-016578-3.

- ^ Studies in the Grammar and Lexicon of Neo-Aramaic by Geoffrey Khan, Paul M. Noorlander

- ^ Studies in the Grammar and Lexicon of Neo-Aramaic, Geoffrey Khan, Paul M. Noorlander

- ^ Semitic Languages: Outline of a Comparative Grammar - p. 464

- ^ Brockelmann (GVG 1 §19)

- ^ Akkadian influences on Aramaic (Assyriological Studies) by Kaufman, Stephan A.

- ^ Folmer, Margaretha (11 March 2022). Elephantine Revisited. Penn State Press. p. 89. ISBN 9781646022083.

… especially since in the eighth century BCE an Akkadian influence had already exerted itself even on Aramaic in the west.…

- ^ Shannon Dubenion-Smith; Joseph Salmons (15 August 2007). Historical Linguistics 2005. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 247. ISBN 9789027292162.

…Western Neo-Aramaic (Spitaler 1938; Arnold 1990), which is attested in three villages whose speakers just a few generations ago were still entirely Christian.

- ^ Wolfhart Heinrichs (14 August 2018). Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Brill. p. 11. ISBN 9789004369535.

The inhabitants of Bakh'a and Jubb'Adin are Muslims (since the eighteenth century), as is a large portion of the people of Ma'lula, while the rest have remained Christian, mostly of Melkite (Greek Catholic) persuasion. The retention of the "Christian" language after conversion to Islam is noteworthy.

- ^ Studies in Islamic History and Civilization, p.308

- ^ Parisot, Jean (1898a, "Le dialecte de Maʕlula. Grammaire, vocabulaire et textes.", p. 270):"D'áprès leurs traditions, ġaddan ʕan ġaddin, les habitants de ce village et des lieux avoisinants raient des émigrés du pays de Sendjar. Ils disent qu'à une époque ancienne, urs ancêtres voulant se soustraire aux vexations des musulmans qui avaient ivahi la partie septentrionale de la Mésopotamie, auraient traverse l'Euphrate le désert de la Palmyrène, pour se réfugier définitivement sur les hauts ateaux de la Syrie orientale, à trois cents lieues de leur pays d'origine."

- ^ Ma'ayeh, Suha Philip (2012-10-14). "Syria's Christians face uncertain future". The National. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ Sabar, Ariel (18 February 2013). "How To Save A Dying Language". Ankawa. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ Oriens Christianus (in German). 2003. p. 77.

As the villages are very small, located close to each other, and the three dialects are mutually intelligible, there has never been the creation of a script or a standard language. Aramaic is the unwritten village dialect...

- ^ Maissun Melhem (21 January 2010). "Schriftenstreit in Syrien" (in German). Deutsche Welle. Retrieved 15 November 2023.

Several years ago, the political leadership in Syria decided to establish an institute where Aramaic could be learned. Rizkalla was tasked with writing a textbook, primarily drawing upon his native language proficiency. For the script, he chose Hebrew letters.

- ^ Beach, Alastair (2010-04-02). "Easter Sunday: A Syrian bid to resurrect Aramaic, the language of Jesus Christ". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 2010-04-02.

- ^ Archived at Ghostarchive and the Wayback Machine: "أرض تحكي لغة المسيح". YouTube. 11 February 2016.

- ^ "Aramaic singing festival in Maaloula for preserving Aramaic language – Syrian Arab News Agency". 10 September 2016.

- ^ a b Francis, Issam (10 June 2016). L'Arameen Parle A Maaloula – Issam Francis. Lulu.com. ISBN 9781365174810.

- ^ "Ma'luli". Aramaic Bible Translation.

- ^ "Bible - Rinyo.org". www.rinyo.org.

- ^ "Data" (PDF). scriptureearth.org.

- ^ Eid, Ghattas; Seyffarth, Esther; Rihan, Emad; Arnold, Werner; Plag, Ingo (2022). "The Maaloula Aramaic Speech Corpus (MASC)". doi:10.5281/zenodo.6496714.

- ^ Eid, Ghattas, Esther Seyffarth & Ingo Plag. 2022. The Maaloula Aramaic Speech Corpus (MASC): From printed material to a lemmatized and time-aligned corpus. In Proceedings of the 13th Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC 2022), 6513–6520. Marseille. http://www.lrec-conf.org/proceedings/lrec2022/pdf/2022.lrec-1.699.pdf.

- ^ Werner, Arnold (2011). Western Neo-Aramaic. In Stefan Weninger (ed.), The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook: Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton. pp. 685–696.

- ^ "الأبجدية المربعة | PDF".

- ^ New Testament in Western Neo-Aramaic (Serta/Arabic)

- ^ "襄阳阂俑装饰工程有限公司". www.aramia.net.

- ^ "Search Entry". www.assyrianlanguages.org. Retrieved 2024-02-06.

- ^ Das Neuwestaramäische: Volkskundliche Texte aus Maʻlūla, p. 144

- ^ Frédéric Pichon (27 September 2011). Maaloula (XIXe-XXIe siècles). Du vieux avec du neuf (in French). Presses de l’Ifpo. p. 95. ISBN 9782351593196.

…Eli Smith raconte son court séjour de 1834 : "In our journey in 1834, instead of taking the direct road to Hums, we turned to the left, and ascended among the higher parts of the mountain. (...) We found Saidnaya with its nunnery, resembling a formidable fortress, situated high up on the third. From hence, we proceeded on the eastern side of this ridge to Maaloula, which is situated in a sublime glen at its foot. Beyond Maaloula, we crossed to the western side by a remarkable gap, and found Yebrud at its northern extremity. At Nebk we joined the ordinary road from Damascus to Hums. District of Maaloula. The three villages in this district, are remarkable for speaking still a corrupted Syriac. It is spoken equally by Muslims and Christians. I found among them many Syriac manuscripts ; but they were unable to read or understand them. So far as I have been able to learn, after extensive and careful inquiry, Syriac is now spoken in no other places in Syria. The Syrians, i.e. Jacobites, and papal Syrians, mentioned in the lists as inhabiting other places, speak only Arabic."

- ^ Bosworth; Van Donzel; Lewis; Pellat. THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA OF ISLAM. Brill. p. 308.

Since the Aramaic of Edessa was formerly the liturgical language of these Christians of Byzantine rite, a certain number of Syriac manuscripts from the monasteries and churches of Maʿ lūlā have come down to us, but most were burnt on the orders of a bishop in the 19th century.

- ^ CLASSICAL SYRIAC. Gorgias Handbooks. p. 14.

In contrast to "Nestorians" and "Jacobites", a small group of Syriacs accepted the decisions of the Council of Chalcedon. Non-Chalcedonian Syriacs called them "Melkites" (from Aramaic malka "king"), thereby connecting them to the Byzantine Emperor's denomination. Melkite Syriacs were mostly concentrated around Antioch and adjacent regions of northern Syria and used Syriac as their literary and liturgical language. The Melkite community also included the Aramaic-speaking Jewish converts to Christianity in Palestine and the Orthodox Christians of Transjordan. During the 5th-6th centuries, they were engaged in literary work (mainly translation) in Palestinian Christian Aramaic, a Western Aramaic dialect, using a script closely resembling the Estrangela cursive of Osrhoene.

- ^ "The west Syriac tradition covers the Syriac Orthodox, Maronite, and Melkite churches, though the Melkites changed their Church's rite to that of Constantinople in the 9th-11th centuries, which required new translations of all its liturgical books.", quote from the book The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, p.917

- ^ Arman Akopian (11 December 2017). "Other branches of Syriac Christianity: Melkites and Maronites". Introduction to Aramean and Syriac Studies. Gorgias Press. p. 573. ISBN 9781463238933.

The main center of Aramaic-speaking Melkites was Palestine. During the 5th-6th centuries, they were engaged in literary, mainly translation work in the local Western Aramaic dialect, known as "Palestinian Christian Aramaic", using a script closely resembling the cursive Estrangela of Osrhoene. Palestinian Melkites were mostly Jewish converts to Christianity, who had a long tradition of using Palestinian Aramaic dialects as literary languages. Closely associated with the Palestinian Melkites were the Melkites of Transjordan, who also used Palestinian Christian Aramaic. Another community of Aramaic-speaking Melkites existed in the vicinity of Antioch and parts of Syria. These Melkites used Classical Syriac as a written language, the common literary language of the overwhelming majority of Christian Arameans.

- ^ Das Neuwestaramäische Wörterbuch: Neuwestaramäisch von Werner Arnold, The Western Neo-Aramaic Dictionary: Western Neo-Aramaic by Werner Arnold

- ^ Western Neo-Aramaic Vocabulary by Lambert Jungmann

Sources

[edit]- Arnold, Werner (1990). "New materials on Western Neo-Aramaic". Studies in Neo-Aramaic. Atlanta: Scholars Press. pp. 131–149. ISBN 9781555404307.

- Arnold, Werner (2008). "The Roots qrṭ and qrṣ in Western Neo-Aramaic". Aramaic in Its Historical and Linguistic Setting. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 305–311. ISBN 9783447057875.

- Arnold, Werner (2012). "Western Neo-Aramaic". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 685–696. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Beyer, Klaus (1986). The Aramaic Language: Its Distribution and Subdivisions. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 9783525535738.

- Brock, Sebastian P. (1989). "Three Thousand Years of Aramaic Literature". ARAM Periodical. 1 (1): 11–23.

- Khan, Geoffrey (2019). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialects and Their Historical Background". The Syriac World. London: Routledge. pp. 266–289. ISBN 9781138899018.

- Kim, Ronald (2008). "Stammbaum or Continuum? The Subgrouping of Modern Aramaic Dialects Reconsidered". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 505–531.

- Weninger, Stefan (2012). "Aramaic-Arabic Language Contact". The Semitic Languages: An International Handbook. Berlin-Boston: Walter de Gruyter. pp. 747–755. ISBN 9783110251586.

- Yildiz, Efrem (2000). "The Aramaic Language and its Classification". Journal of Assyrian Academic Studies. 14 (1): 23–44.

External links

[edit]- Yawna – Maaloula Aramaic a non-profit educational initiative dedicated to the preservation of Aramaic – the language of Jesus – and the rich cultural heritage of Maaloula.

- Western Neo-Aramaic alphabet and pronunciation at Omniglot

- Samples of spoken Western Neo-Aramaic at the Semitisches Tonarchiv (Semitic Audio Archive)

- The dialect of Maaloula. Grammar, vocabulary and texts. (1897–1898) By Jean Parisot (in French): Parts 1, 2, 3 at the Internet Archive.